09 Jun How journalists use data to investigate wildlife crime in Asia

Takeaways from a #WildEye discussion among diverse journalists from across Asia about their experiences of using data to produce wildlife crime investigations

Path finders: Some of the pioneering journalists who shared their experiences of using data to tell compelling wildlife crime stories, to mark World Environment Day 2021

Just over a year since the launch of the pioneering #WildEye Asia platform, we brought together some of our grantees to reflect on what we learnt from the project, the challenges they faced and how they overcame these.

Investigative and data journalists from the Philippines, Vietnam, India, Indonesia and Malaysia shared insights from their stories, touching on the difficulties of accessing official data in many countries, a general lack of support from government and law enforcement agencies, weak laws that often are not implemented, and the importance of telling these stories.

The opportunity to gather such a diverse group of journalists led us to co-host a webinar titled #WildEye Journalists Talk: Investigating wildlife crime in Asia, to mark international World Environment Day on June 5 2021.

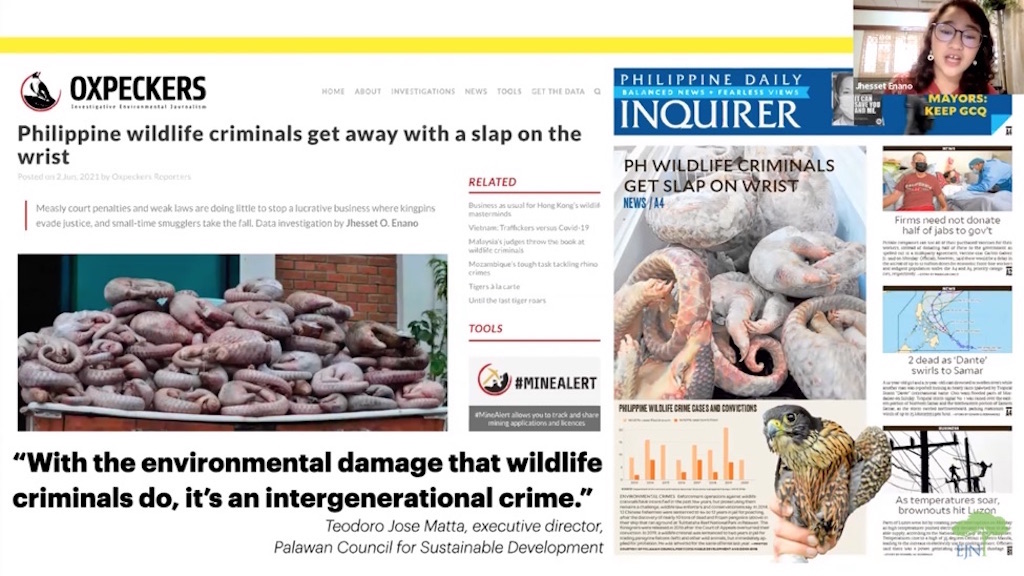

Data trail: Jhesset O. Enano, environment reporter for the Philippine Daily Inquirer, said she overcame her data difficulties by approaching multiple agencies and wading through different kinds of documents to verify information

‘Above all else, show the data’

Accessing data was the biggest challenge that the #WildEye Asia journalists faced.

Days after her investigation was published by Oxpeckers and on the front page of the Philippine Daily Inquirer, environment journalist Jhesset O. Enano described the data she managed to get ahold of as having “gaps and inconsistencies”.

Her investigation showed that in the past seven years, while more cases are making it to court and more convictions are being secured in the Philippines, there is still a lot of work to be done. The next step, she reported, is an amendment to the wildlife laws to increase the length of sentences and monetary value of fines meted out by the courts.

Enano said she overcame her data difficulties by approaching multiple agencies and wading through different kinds of documents to verify the information she was presented with. You can download the data used in her investigation here.

Vo Kieu Bao Uyen, a freelance investigative journalist from Vietnam, had an even tougher time collecting data. Government and law enforcement agencies did not offer any help or support, she said, and in the end she created her own dataset. By sifting through local media reports, the library of law, documents from the courts and those supplied by wildlife protection NGO Education for Nature – Vietnam (ENV), Bao Uyen collected information on more than 300 individual court cases.

Her investigation, much like Enano’s, exposed a justice system that lets criminals continuously get off lightly. In this instance, improved laws already exist, but now the courts need to follow through, she reported.

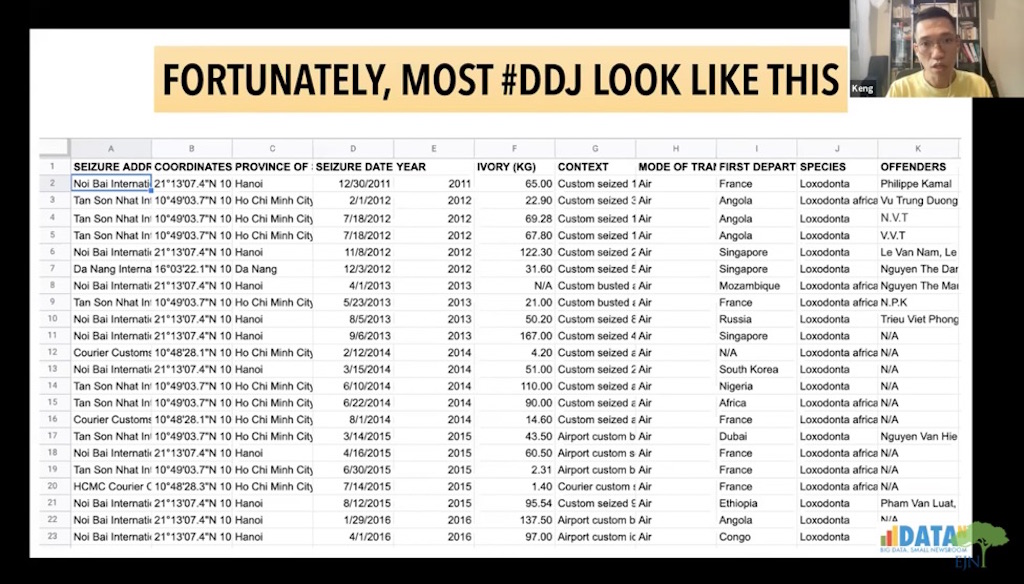

Compelling story: Kuek Ser Kuang Keng discussed an investigation in Vietnam in which two local journalists analysed 10 years’ worth of data to determine if illegal wildlife trade would come back stronger after the Covid-19 pandemic

Data journalism isn’t (always) an elite beat

Data journalism trainer Kuek Ser Kuang Keng, the founder of DataN, was invited to join the webinar to talk about data journalism and answer perceptions that it is an elite beat. “It depends on the kind of data journalism,” Keng said.

He pointed out that while some data journalism projects come from large and well-resourced newsrooms like the New York Times and Washington Post, there are lots of other smaller newsrooms pulling it off – well. In a recent investigation put together by the Environmental Reporting Collective, he said, reporters analysed a decade worth of data that tracks wildlife trafficking in Vietnam before and during the pandemic.

“Using simple (but effective) visualisations, this investigation relied on the richness of the data to tell a compelling story,” he said.

#WildEye grantee Richa Syal pointed out that collecting, collating and analysing data for journalistic investigations is often a task tackled by freelancers or smaller newsrooms, with little support and even less funding.

For her investigation, Malaysia’s judges throw the book at wildlife criminals, she focused on trends, patterns, changes and outliers in the data, and ensured that she verified the data with experts. You can download the data she collected as part of her investigation here.

“It’s important to humanise the numbers,” she said. You can do this by “adding voices, stories and names to the numbers you are trying to represent”.

‘Humanise the numbers”: Data journalist Richa Syal advised ‘adding voices, stories and names to the numbers you are trying to represent’

‘Genius is in the idea. Impact, however, comes from action’

Indian investigative journalist Sadiq Naqvi said he has seen real change since publishing his #WildEye investigation in August 2020 about how insurgents in the North-East have been facilitating the syndication of rhino poaching in and around Assam’s famous Kaziranga National Park.

Since late last year, he said, the group of insurgents he reported on has been brought to the attention of law enforcement. This coincides with an increase in arrests since the pandemic began in 2020, as well as approximately three incidents of rhino poaching in the area. You can read about these incidents on the #WildEye Asia map.

Naqvi also spoke about the likelihood of one of the biggest cases mentioned in his investigation being taken on by the National Investigation Agency, which is India’s counter-terrorist task force. Rhinos are an important symbol of Assam’s culture, and “there has been a lot of effort to make sure that all these poachers are not successful”, he said.

Indonesian data journalist Rezza Aji Pratama spoke about changes in the way laws are being used in Indonesia to counter wildlife crime. His investigation, produced in collaboration with the Indonesian Data Journalism Network’s executive director, Wan Ulfa Nur Zuhra, measured the impact the country’s new Quarantine Act is having on successful convictions. According to Pratama, more prosecutors are successfully applying the law and, in turn, putting pressure on the government to amend other outdated and ineffective laws.

#WildEye Asia, a data journalism project of Oxpeckers Investigative Environmental Journalism and Internews’ Earth Journalism Network, allows you to track illegal wildlife trade throughout the continent.

You can now watch the recording of this webinar and access all the presentation slide decks on our website.