16 Aug Online trade: the devil’s in the data

Law enforcement agencies are creating new ways to combat online illegal wildlife trade. A centralised data repository is crucial to their success, writes Roxanne Joseph

Behind bars: There are multiple sources of wildlife-related trade data available, with the IUCN Red List and CITES being two of the most comprehensive. Photo: bedya/Adobe

As of this year, more than half the world’s population is online and actively using the Internet. Although the reasons for web use differ, a significant portion relates to browsing, and buying and selling from online marketplaces.

Advertising illegal products itself is not against the law, which makes questioning and researching a particular advertisement important, especially when it comes to animals or their parts and products.

Given the difficulty in identifying and monitoring criminal activity online, law enforcement has had to adapt and create new ways of working to combat online illegal wildlife trade. This means a great deal of research, data collection, analysis and training in how to spot criminal activity is needed.

Also, because illicit wildlife trade often takes place between provinces and even different countries, anyone working to combat it needs a deep understanding of existing legislation, and what needs to be done – legally – about it.

‘Security threat’

Online illegal wildlife trade has quickly graduated from being isolated incidents to a “national security threat”, according to a national strategy handed to the police earlier this year. In response there has been a change in direction to mitigate the threat, alongside a more collaborative effort between government agencies and civil society.

Organisations like the Endangered Wildlife Trust (EWT), TRAFFIC and the International Fund for Animal Welfare are working with law enforcement authorities to provide a better understanding of what can be done to combat one of the most undetectable forms of criminal behaviour.

According to Ashleigh Dore of the EWT, collaborative initiatives have seen several successful attempts at decreasing instances of online illegal wildlife trade. In one case, collaboration with a group of law enforcement agents who attended an EWT training course led to the removal of 350 cycads from the illegal trade circuit.

The overall programme, said Dore, is aimed at reducing “trade-related threats that impact on the survival of wild animals and plants”. Her team focuses on five thematic areas: prevention, detection, justice, governance and use. The first three involve working directly with government law enforcement agencies, such as the South African Police Service and the National Prosecuting Authority.

Global problem: Rhino horn for sale on Baidu Tieba, a Chinese social network. Photo sourced

Using the law

One of the major pieces of legislation that has had a positive effect in South Africa is the National Integrated Strategy to Combat Wildlife Trafficking. Approved in May 2017, it recognises the need for a whole government approach, assisted by the efforts of civil society.

Its three main objectives are to strengthen enforcement by actively improving efforts to stop illegal wildlife trade; reducing demand by raising public awareness of the harm and destruction caused by trafficking; and building global cooperation, commitment and public-private relationships.

Guided by this strategy, there has been an increase in investigative efforts by law enforcement agencies. This is primarily because wildlife trafficking has, in many instances, become a serious organised crime and tracking down syndicates is a priority.

Silo effect

Another challenge to the fight against online illegal wildlife trade is the “silo effect”, the name given to a lack of collaboration and information-sharing between police stations, police units, national parks, government departments, security agencies, the defence force and security companies. In short, these entities focus only on the areas directly around them and ignore what happens beyond that.

This is where the importance of data collection, analysis and sharing comes in. Considering the impact that a consolidated database related to online illegal wildlife trade could have, the concept makes a lot of sense. Collectively, law enforcement – with the support of civil society – can achieve more than interventions on a smaller, or more localised, scale.

If officials are able to share successful instances of identification, monitoring and prosecution, others elsewhere can emulate their processes. A consolidated, shared database will also help in cases of organised crime, especially when it occurs online. By encouraging transparency, successful replication can follow.

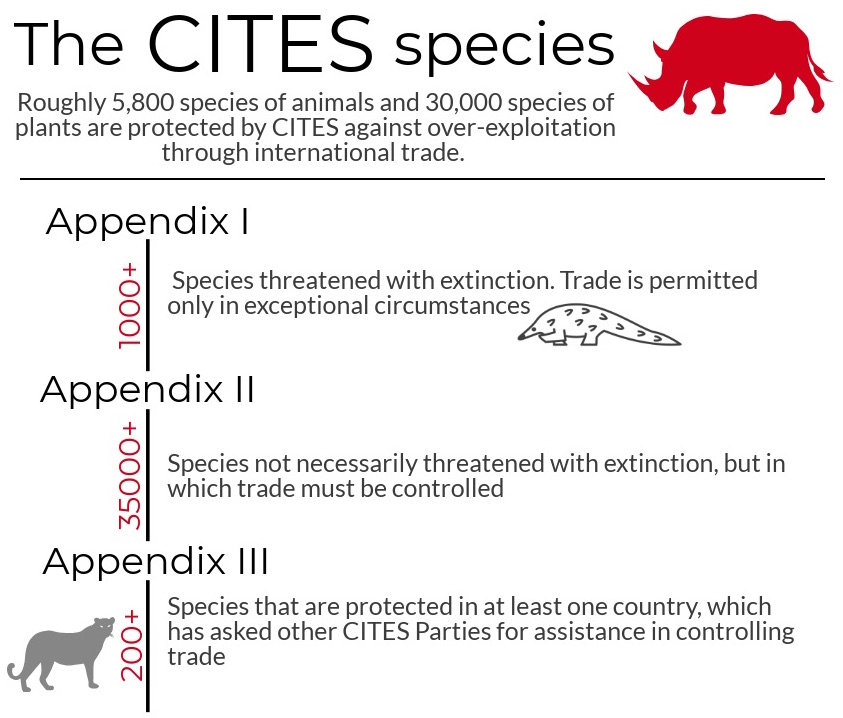

Under threat: The species focused on in this series of articles – pangolins, sungazer lizards, leopards and rhinos – are listed on Appendices I and II of CITES. Infographic: Roxanne Joseph

Shared database

A shared database has three other major benefits. First, it produces better-quality data as a result of having to be rigorous and sufficiently documenting processes. It teaches users, such as law enforcement, best practices for working with data, including organisation, documentation, and storage and security.

Second, it creates open access, as it raises public awareness and, in aiding law enforcement and civil society, invites the average online user to gain better understanding of what it is they’re buying, selling or seeing on-screen. Finally, through each of these, it instills greater faith in law enforcement among the public.

Data sourcing, analysis and reporting are used by governments, civil society and the media to track and expose all kinds of wrongdoings, including online illegal wildlife trade. These are and should continue to be shared with Internet users – everywhere in the world – to promote transparency and wildlife sustainability.

So what’s already out there?

• The Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES): Nearly 6,000 species of animals (including the four we have highlighted throughout this series of articles – pangolins, sungazer lizards, rhinos and leopards) and 30,000 species of plants are protected by CITES against over-exploitation through trade. They are grouped according to how endangered they are.

• The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: This is regarded as the most comprehensive, objective global approach for evaluating the conservation status of plants and animals. Nearly 100,000 species have been assessed to date.

• Wildlife Cybercrime report by the International Fund for Animal Welfare: The results of a six-week investigation into online wildlife trade in Africa, which found nearly 1,000 endangered and threatened wildlife species advertised across over 30 online marketplaces and three social media platforms.

• TRAFFIC: An in-depth overview of legal trade of CITES-listed species from Africa to East and Southeast Asia, over a period of nine years (2006 to 2015).

5. Oxpeckers Poachtracker and Rhino Poachers Court Cases data platforms: The former is used to find statistics on rhino deaths and poaching incidents in southern Africa, and its usefulness can be seen in numerous related data-driven investigations. The latter is a dataset, collected over years that lists information about rhino-poaching cases that have gone to court. Over a period of four years, nearly 1,200 arrests have been documented in South Africa in connection with rhino poaching.

These five sources have made data readily accessible to anyone who wants to see and use it, and there are several others out there. What the network of organisations working to combat online illegal wildlife trade lack is a centralised data repository; one that demonstrates transparency, learning and sharing.

This article is part of a series, in partnership with Oxpeckers, on online illegal wildlife trade. Research was funded by the Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime, and support was provided by the Endangered Wildlife Trust, TRAFFIC and the International Fund for Animal Welfare

This article is part of a series, in partnership with Oxpeckers, on online illegal wildlife trade. Research was funded by the Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime, and support was provided by the Endangered Wildlife Trust, TRAFFIC and the International Fund for Animal Welfare