18 Jan How green is this hydrogen valley?

Puros is the northern-most of three ‘hydrogen valleys’ identified in the Namibian government’s GH2 masterplan. John Grobler visited to find out why

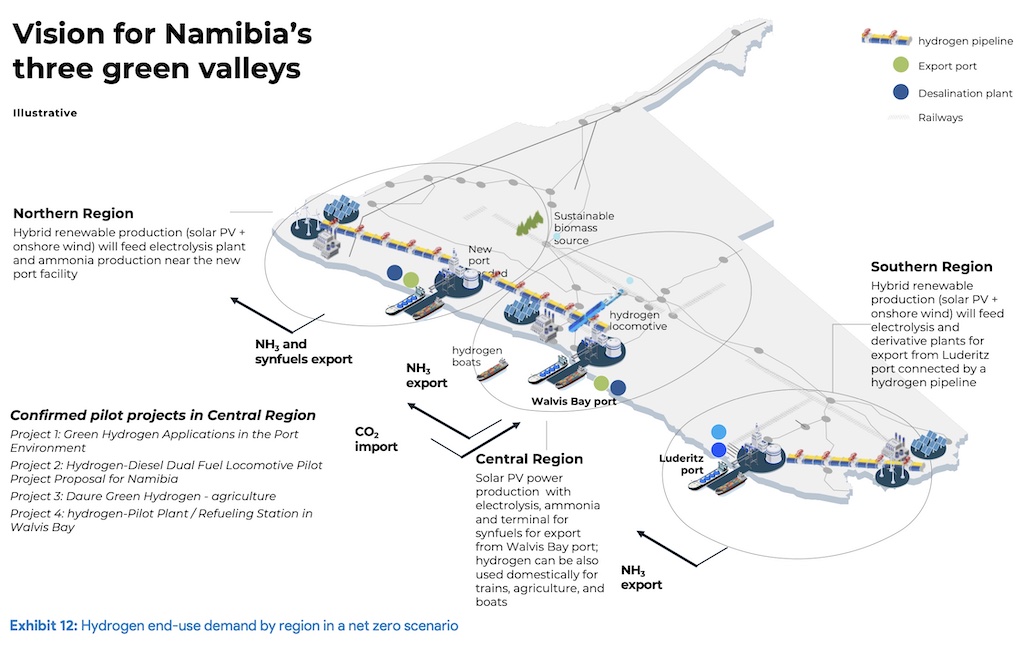

The Bigger Picture: how the Namibian government envisages the US$190-billion green energy development plan will look in its final form. It will include two new gas-to-power plants at Walvis Bay and Oranjemund, the latter to supply 400MW of electricity to South Africa. Source: Namibia GH2 Strategy, 2nd Revision

In the brave new world of Namibian green hydrogen, the contrast between lofty ambition and the stark reality on the ground could not be starker than in Puros: in a place selected as one of three future hydrogen and ammonia production sites to supply space-age fuel and fertiliser to Europe and Asia, everyone here still cooks and heats themselves with firewood.

Located two days’ driving north of Windhoek in the harsh rock desert at the confluence of the Hoarusib and Gommadommi Rivers of the north-western Kunene Region, Puros is the northern-most of three “hydrogen valleys” identified in the Namibian government’s 2022 Green Hydrogen and Derivatives Strategy masterplan.

The selection of Puros is due to its relative proximity to Cape Fria, a small bay about 150km away as the crow flies to the north-west on the Atlantic coast, and where the official green hydrogen (GH2) masterplan indicates a new deep-water port is to be constructed for the export of GH2 and ammonia.

In early December 2022, director-general of the National Planning Commission Obeth Kandjoze, accompanied by a state television crew, flew to Puros in a chartered plane and presented the government’s plans for a 970ha GH2-fuelled project to a small audience at the exclusive private lodge overlooking Puros from the opposite bank of the Hoarusib River.

The floodplain known as Puros in the remote northern Kunene Province at the confluence of the Hoarusib and Gommadommi Rivers, where one of the proposed hydrogen-to-ammonia plants is to be located as the Northern Region Green Hydrogen Valley. This part of the plan depends on the construction of a new port at Cape Fria on the Atlantic coastline in the Skeleton Coast Park, about 170 north-west from here. Photos: John Grobler

Community conservancy

Across the river a year later, very few among the 300 members of the Kasoana and Kasupi clans and their extended families could recall any details of Kandjoze’s visit.

“Yes, I heard about that but I also was not [invited] there,” said Leon Kasupi, chairperson of the Puros community conservancy and owner of one of only two brick-built houses among a motley collection of 50-odd shacks made of rusted zinc sheets and flattened oil drums.

A clip of Kandjoze’s speech was later placed on the internet, he was told. But Puros has no electricity, television or internet access, just a small solar-powered cell-phone tower that allows for basic communication with the outside world.

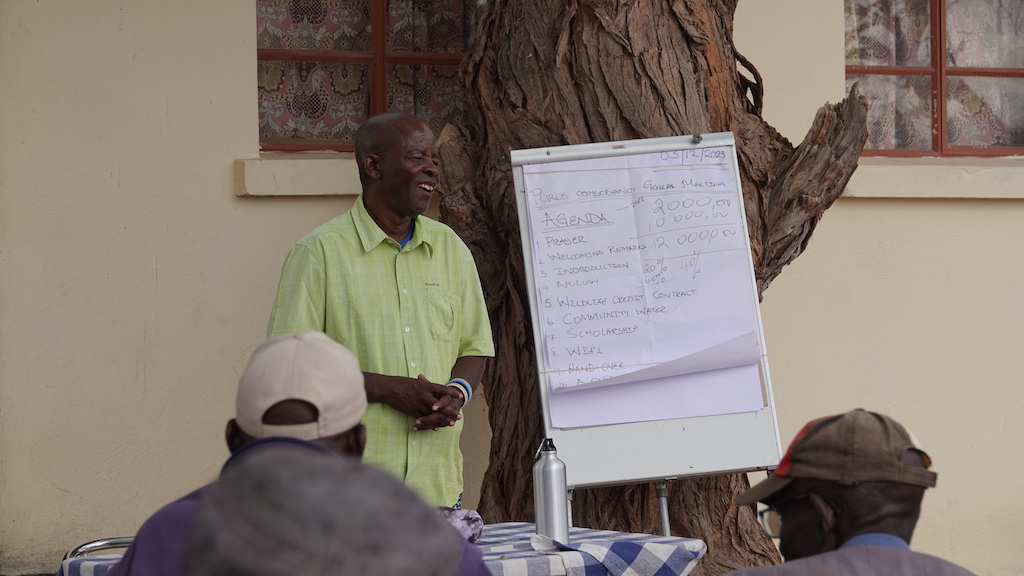

Access to information is a big local issue: on the whiteboard under the big trees around the Puros conservancy where the annual general meeting was about to commence in December 2023, one of the agenda points listed was access to wifi that would require a major upgrade of the cell-phone tower.

Even though he has been living more often in Opuwo of late, Kasupi said neither he nor any of his 12 fellow conservation committee members had ever heard of GH2, green ammonia or any large local agricultural project planned for Puros. Neither was he aware of any plans to construct a new port at Cape Fria.

Given the topography and remote location of Puros, logistics are a challenge. It took a whole year to complete construction of the lodge, using two 4×4 trucks of 7.5 tons capacity, said local tour guide Steve Tjiuro who had worked on that project.

Moving thousands of tons of steel piping and massive tanks needed for an ammonia plant to Puros would be impossible, he said, because the badly rutted track of 100km between Puros and Sesfontein takes up to five hours to drive and can’t be used by any articulated truck.

“Man, it will take them 10 years just to bring in the kind of plant you’re talking about. They will have to blast a new road through all the mountains instead!” he laughed.

Drought-stricken desolation: the Puros community of 300 people from two large families, the Kasoana and Kasupi families, subsists on small livestock farming. The standard local diet is maize porridge and sugar, with milk no longer an option after a devastating seven-year long drought wiped out their cattle herds. Photos: John Grobler

Deep-water port

So why even bother with Puros in the official GH2 blueprint? The answer appeared to be politics and proximity, as in firstly the need for a secure deep-water port along the southern African Atlantic coast, and secondly, connected to off-shore oil exploration.

Both Cape Fria and Angra Point on the Luderitz peninsula have been central to an ambitious national development plan since the late 1990s as key to Vision 2030, formulated under founding president Sam Nujomo to unlock the mineral wealth of Namibia’s remote and arid north-western and south-western regions.

Vision 2030 is, as the current President Hage Geingob wrote in the foreword to the Green Hydrogen and Derivative Strategy masterplan, a continuation of this strategy and is now incorporated as part of his own Harambee Prosperity Plan that is the driving force behind the government’s clean energy strategy.

In the post-independence era, Cape Fria and the construction of a second hydro-electric dam at Epupa Falls became central features of this plan to develop the mineral-rich but otherwise impoverished north-western Kunene Region into a mining mecca.

Despite foreign interest in Namibian mining, there has always been two obstacles: water and electricity, which Nujoma sought to address by building a new hydro-electric dam below the Ruacana Falls, the hydro-electric dam where Namibia obtains about 380MW of its electricity supply. The balance of peak-demand need of about 600MW is imported via the Southern African Power Pool from as far away as Mozambique, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

While extra electricity requirements to some extent could be met, the biggest obstacle had always been water, said a veteran geologist who asked to not be named for professional reasons. “You can always make a plan to generate your own electricity, but you cannot do the same with water,” he said.

Flashflood in the Hoarusib River: early summer rainfalls in the catchment areas far upstream from Puros cause regular flash floods that sustain the wildlife in the area. Photos: John Grobler

Hydro-electric dam

For the duration of his 15-year rule as president, Nujoma tried to convince the local Himba residents of Epupa Falls that a large new hydro-electric dam on the Kunene River that forms the border with Angola’s Namibe Province would bring jobs and development.

In terms of Vision 2030, the extra water and electricity of a new dam would enable developing Cape Fria into a mineral exports port as well as function as a harbour for fleets fishing in the still abundant waters off the Skeleton Coast, drastically reducing the operational cost of fuel needed for operating from Walvis Bay, more than 560km away to the south.

The Himbas were not swayed: they do not eat fish, and drowning their ancestral lands and grave sites under a man-made lake did not appeal to them. Even moving the proposed site downstream from the Epupa Falls did not gain their approval, and after a two-year-long environmental and feasibility study, the project failed to get off the ground for a combination of environmental, social and financial reasons.

Undeterred, Nujoma’s successor Hifikepunye Pohamba persisted with the plan, commissioning a second Cape Fria feasibility study in 2008 that was done by a Russian engineer and specialist on large hydro-electric projects.

A senior Namport manager, speaking in his private capacity as he was not authorised in advance by the company’s board to speak to the media, confirmed that the second feasibility was also rejected by Namport management. It was deemed not only too expensive, but also direct competition to the under-utilised and financially struggling port of Walvis Bay, he explained.

The only form of a cash economy income in Puros is from tourism and a rental income from the local lodge, recently sold to Abercrombie & Fitch. At the annual general meeting of the Puros Conservancy no one knew of the green hydrogen plans for their little settlement. Photos: John Grobler

Vision 2030

The 2008 study included detailed plans for a network of new railway lines and roads connecting Cape Fria via Namibia’s central northern regions to the Trans-Caprivi highway between Namibia and the Copperbelt of Zambia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Fifteen years later, this same plan has become central to Namibia’s ambitious Green Hydrogen and Derivative Strategy masterplan.

“The genesis of Namibia’s ambition to become an industrialised nation hails from Vision 2030, a public policy paper we crafted under the tutelage of our Founding President, Dr Sam Nujoma,” President Geingob wrote in the introduction to the 2022 masterplan.

The masterplan – more a vision than a practical plan – is the continuation of Vision 2030’s ambition to lift the standard of living of rural people to the same level as their counterparts in the developed world by opening up the mineral-rich but arid Namib desert.

Development obstacle? The road to Puros from Sesfontein is only 100km long, but takes at least four hours to negotiate and is not suited to any articulated truck that would be needed to transport an entire industrial plant to set up in Puros. Photos: John Grobler

Kaoko Fria

A key component of Vision 2030 is food self-sufficiency, and the government has since 2011 been investing billions of rands into a “Green Scheme” setting up state-run agricultural schemes all over the country, including one at Warmquelle 140km west of Puros. But while Warmquelle – like the nearby Sesfontein (“Six Fountains”) – has strong artesian water, the soil is of poor quality and not suited to agriculture unless heavily fertilised.

In late November 2023, a company called Kaoko Fria Investments published a public notice of an environmental impact assessment for Cape Fria that includes the construction of a “… hyper-modern Atlantic City” and a new network of roads and railways between Cape Fria and Katima Mulilo in the far north-eastern Zambezi Region “… that will snow-ball into a dry-port at Katima Mulilo”, according to Koako Fria’s managing director Michael Petrus.

In Puros, the local conservancy committee was as non-plussed by the Kaoko Fria project as the green hydrogen-to-ammonia plan mooted by the National Planning Commission. None of this made much sense in a remote settlement whose only connection to the outside world was a small dirt road and wonky cell-phone tower, they said.

Kavisana Kasoane, the manager of the conservancy’s small bush lodge, did volunteer some information: Kaoko Fria’s Michael Petrus was recently awarded the sole rights to transverse the Tsau//Khaeb Park between Lüderitz and Oranjemund, he recalled.

This transit concession is potentially worth a fortune because the Tsau//Khaeb National Park, in spite of having been declared a national park by the then-outgoing president Sam Nujoma in 2004, is not open to the public except for on the Lüderitz Peninsula (see Green concerns over green hydrogen). Anyone wishing to enter into or travel through the park is required to pay a fee of R3,200 per person to the concession holder.

Koako Fria Investments was only established on July 5 2022, two weeks after the initial Request for Proposals for green hydrogen projects was issued in mid-June 2022. Although this reporter registered as an interested party to the EIA study, no further communications have been received from their environmental consultant. Petrus, who is based in Walvis Bay, did not respond to repeated emailed queries and requests for comment.

John Grobler is a Namibia-based associate at Oxpeckers Investigative Environmental Journalism. This investigation is part of a #PowerTracker series on green hydrogen, supported by the Heinrich Böll Foundation. Find the Oxpeckers #PowerTracker tool and investigations here