17 Nov Green concerns over green hydrogen

Namibia’s ambitious GH2 project poses threats to a sensitive biodiversity hotspot and local communities, critics say. John Grobler investigates

The resident heaviside dolphin population is the smallest of all dolphin species. Photo courtesy Lüderitz Marine Research

The largest of five green hydrogen (GH2) projects approved by the Namibian government is sited within the limits of the Tsau//Khaeb National Park on the Lüderitz Peninsula – a region identified by both the government and the international botanical community as one of the world’s top biodiversity hotspots.

The GH2 expansion could come at the expense of local communities and ecosystems, in particular the Karoo ecosystem unique to Southern Africa, critics say. Namibia is planning a series of million-dollar investments to become a major GH2 supplier to Europe and Japan as early as 2026 (see Question marks over Namibia’s green hydrogen plans).

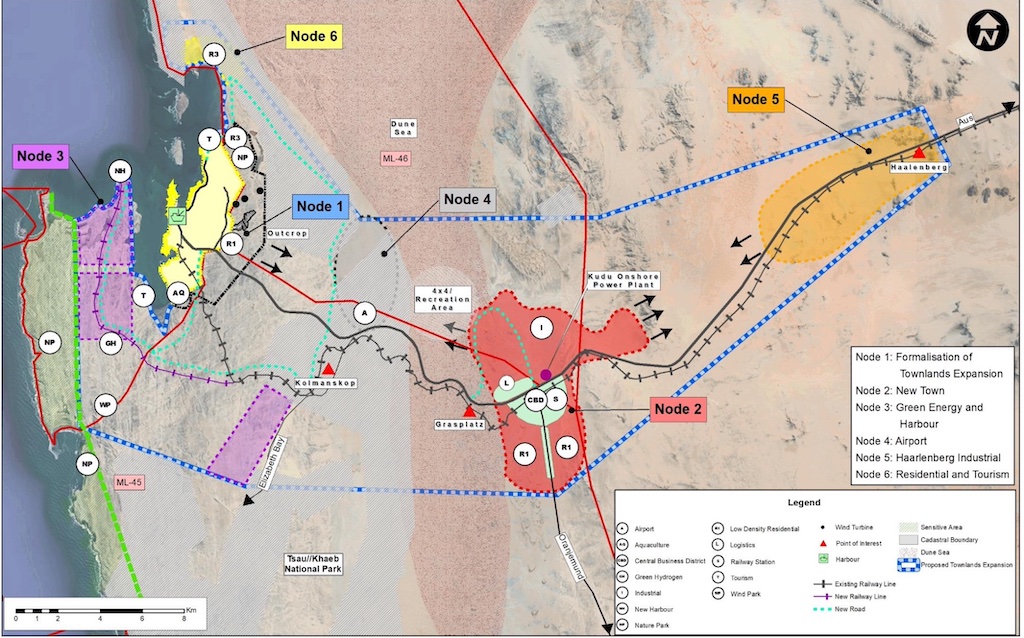

Hyphen’s GH2 complex along the southwestern coast near the town of Lüderitz would include the construction of a new deepwater port, a 6GW wind and solar farm, a mega desalination plant that turns sea water to fresh water, and a conversion plant capable of transforming hydrogen into 300,000 tons of ammonia fertiliser a year.

The area is the northern-most tip of the succulent Karoo. Photo: John Grobler

Succulent Karoo

Jean-Paul Roux, a retired marine biologist working in the area for decades, said the site around Shearwater Bay on the Lüderitz Peninsula where the new deepwater port to accommodate bigger vessels would be built, is particularly vulnerable.

“This is the northern-most tip of the succulent Karoo,” he said, pointing out where the peninsula ends at Angra Point directly across the bay from the current Lüderitz port.

Upon completion, the GH2 complex could be as large as 2,000km2 and would require billions of litres of desalinated water to produce 300,000 tons of ammonia a year, according to Roux’s estimates.

“Here you can find up to 1,000 different plant species in just one square kilometre, some so small no bulldozer operator will even notice them,” he said, pointing out signs of the local fauna and flora populations where Hyphen is planning to put up its desalination and ammonia plants.

A lagoon teeming with flamingoes would be affected. Photo: John Grobler

Marine impacts

This would have a huge impact on Shearwater Bay and the adjacent Sturmvogelbucht, a lagoon teeming with flamingos and the resident heavy-sided dolphin population that Roux has been studying for years.

“This is the only place along the Southern African coast where you can watch them from your car,” he pointed out as this smallest of all dolphin species approached to within a few metres of the beach.

A copy of the Lüderitz Town Council’s proposed expansion plan shows the Hyphen site will occupy about one-third, or about 2,000ha, of the entire east-facing side of the small bay between Angra Point and the town across the bay.

Construction work could be particularly damaging because the site would require millions of tons of rock to fill the bay for the infrastructure planned, the retired state marine scientist said.

“That’s going to need a lot of blasting – and after the first blast, all the dolphins will be gone forever,” Roux said.

A copy of the Lüderitz Town Council’s proposed expansion plan. Graphic: Fanis Kollias/Spoovio

Fisheries threatened

The peninsula is also the only publicly accessible area around the entire Lüderitz region. Some of Hyphen’s infrastructure will reduce public access to the peninsula, especially with the port expansion on the coast. The locals’ only access to the sea would be the polluted Agate Beach on the northern end of the enclave, situated down-wind from the last few local fishing factories and the over-flowing municipal sewage plant.

That would have a significant impact on local lobster fishing and rock angling, locals say. Crayfish fisheries, one of the area’s tourism attractions and an informal source of income for the local population, would be affected.

“The people in the poorest areas have nowhere else to go, they are going to strip this bay clean of everything,” said Gerd Kessler, a fourth-generation Buchter as locals call themselves, referring to a potential spike in illegal fisheries.

Lüderitz fishing harbour. A new seawall could have unpredictable results on the currents. Photo: John Grobler

Currents in the bay

Owner of Five Roses Aquaculture (Pty) and three smaller oyster-breeding operations, Kessler employs 100 people permanently in supplying a million oyster seedlings a month to four other local oyster farms in the small bay and adjacent lagoon.

Building a massive new seawall and harbour at Angra Point at the northern entrance to the bay could have unpredictable results on the currents in the bay, he cautioned. When the port was first expanded in the late 1960s by filling in the channel between the town and Shark Island, the sea quickly stripped away the town’s only little beach inside Robert Harbour, as the port area is known.

His biggest concern was how Hyphen plans to dispose of the brine from their desalination plant and other quite possibly poisonous waste from their hydrogen.

A free flow of the currents is essential for the health of the bay, otherwise it will turn the heavier brine into a thick dead slime that will choke all the life out of the sea bottom, and in due course the whole bay as well, he explained.

“You can’t just dump that anywhere, you have to make sure you use the currents to disperse it,” Kessler said. “And Hyphen is not saying anything about their plans in this regard.”

Patrick Neib, an unemployed resident of the Nautilus township behind Luderitz, moved here in 2015 in search of a better job that is still to materialise.

He said he only found out about Hyphen’s plans via social media as most of Hyphen’s public meetings took place in Keetmanshoop, the regional capital 350km away from Lüderitz. The secrecy and technical jargon used by Hyphen and its consultants made it impossible for the ordinary layman to understand or access any opportunities, he said.

“There is just no public discussion about the benefits for ordinary people like me, or what price we are to pay for green hydrogen development,” he said. “My question is, who or what is really behind all of this?”

Entrance to the the Tsau//Khaeb National Park. Impacts inside the park may be compensated elsewhere. Photo: John Grobler

Environmental impact assessment

Construction of phase one of the Lüderitz port is set to begin in the fourth quarter of 2024, Andrew Kanime, chief executive of Namport, reportedly said recently. “Two weeks ago, we completed the stakeholder consultation for the finalisation of the environmental impact assessment,” he was quoted as saying at the EU Namibia Business Forum.

According to the report, he said phase one would involve expansion of the existing port to enable Hyphen to import construction material; phase two the development of a new port adjacent to the existing facility and a green ammonia export facility which is expected to be completed by 2028; and in phase three, the port capacity would be ramped up to accommodate output from new green hydrogen projects.

Bart de Smet of Dutch fund manager Invest International – one potential investor in the project – was dismissive of environmental concerns. The project, he said in an interview, “is in an area in which at this moment there’s nothing apart from desert. I have been there.”

De Smet said “no international financing organisation” would back a project without an environmental impact assessment, but that impacts to the Tsau//Khaeb National Park could be compensated elsewhere.

“It’s just normal that there will be impacts, but the art of the game is to find measures that can be mitigated,” he said.

Expansion of the existing Lüderitz port is scheduled to begin in the fourth quarter of 2024. Photo: John Grobler

Environmental consultants

“No green energy project can be implemented without some environmental impact and Hyphen’s objective is to minimise environmental impacts to the largest extent possible,” Hyphen CEO Marco Raffinetti said in an interview.

The company had hired environmental consultants SRL to draft an assessment report of the potential impacts, said Hyphen in a written statement. They plan to “avoid the highest environmentally sensitive areas” and minimise impacts “through the technical design of the project”, the company said in the statement.

“Namibia is unique in that some 42% of the entire country (the 35th largest by land mass) comprises of national parks or protected land, with national parks extending the entire length of Namibia’s 1,500km coastline. All of the high quality renewable resources to be found (where there is co-located solar and wind resources) are located in these protected areas,” the statement said.

“This poses a challenge for the development of green hydrogen projects due to these conflicts with the natural environment.”

James Mnyupe, appointed Green Hydrogen Commission by the government in 2020, responded that the focus is on ensuring the green hydrogen project “adheres to international best practices, Namibian and international environmental standards, and aligns with Namibia’s national goals of sustainable development”.

The Tsau //Khaeb National Park is a multi-use park and “has hosted for many decades a plethora of economic activity, including diamond mining, tourism activities and renewable energy projects,” he said. “The government remains committed to implementing the project and other activities that will mutually advance Namibia’s socio-economic agenda while respecting the nation’s flora and fauna.”

John Grobler is an associate at Oxpeckers Investigative Environmental Journalism. This investigation is part of a series titled Shades of Green Hydrogen, a collaboration with Climate Home News supported by Journalismfund Europe’s Investigation Grants for Environmental Journalism