25 Oct Has the DMRE lost control of South Africa’s chrome resources?

South Africa has some of the world’s largest chrome resources, but regulatory problems in the official administration system are aiding the growth of illegal activities in the industry. Andiswa Matikinca investigates

South Africa is the global leader in chrome ore production and the second-largest producer of ferrochrome behind China. The country holds more than 70% of the world’s chrome reserves and 72% of global chromite resources.

Mined chrome is smelted into ferrochrome, which is mainly used in the production of alloys and in the manufacturing of stainless steel and other metals. A large amount of the mineral is found in the Bushveld Complex – a 66,000 square kilometre area located in the Limpopo and North West provinces.

Chrome data

#MineAlert liberated data from a comprehensive map of chrome mining activities in the Bushveld Complex created by mining consultants AmaranthCX in 2020. The data revealed how some of the mining operations are taking place near residential homes in some villages and other operations are next to four protected areas – the Magaliesberg Protected Natural Environment, Kgaswane Mountain Nature Reserve, Verloren Vallei Nature Reserve and Pilanesberg National Park.

The operations include 37 chrome mines, 19 UG2 (low-grade chrome ore) recovery plants, 24 chrome projects that are closed or currently on hold, and 53 ferrochrome smelters and chemical plants.

AmaranthCX chief executive officer Paul Miller says there were multiple chrome washing plants included in the data that seemed to have no known legal source of chrome that could be linked to them – an indication that illegal chrome mining is happening in the area.

The company previously exposed a boom in open pit chrome mining activities adjacent to Witrandjie, a small community west of the Pilanesberg mountain in North West. A GoogleEarth visual shows a stark difference of images taken in the area in February 2019 and August 2020 – in 18 months the size of the mining operations had just about doubled, moving ever closer to the Witrandjie community.

Attempts by AmaranthCX to obtain public records of the mining companies authorised to mine in the area were in vain. Miller maintains that the Department of Mineral Resources and Energy (DMRE) is battling deep systematic issues with its South African Mineral Resources Administration System (SAMRAD).

‘Disclosure-free zone’

#MineAlert reported in February that the SAMRAD portal, which is the official administration system of all mining right and permit applications, was not functional (see Is coal really on its way out in SA?). In an interview with #MineAlert, Miller said this has led to a lack of transparency about South Africa’s coal mining operations which were in fact on the rise.

Miller described the DMRE’s mining permit system as a “disclosure-free zone” due to the fact that mining permits are not publicly disclosed.

“The DMRE does not disclose mining permits anywhere except if they have applied for an environmental impact assessment (EIA) – which they don’t. They just do a basic environmental assessment, they don’t do a full EIA, and if you are lucky enough you will find a document somewhere,” said Miller.

In his probe into the Witrandjie chrome mining activities, Miller found that a number of people from the Witrandjie community had been granted mining permits by the DMRE office in Krugersdorp. The holders of these mining permits then brought in contractors to mine and this also opened a gap for some illegal miners to come into the area.

Issues in the industry

Data from Minerals Council South Africa shows that chrome ore production dropped to 14.5-million tonnes in 2020, from 17.7-million tonnes in 2019. The council’s head of communications, Allan Seccombe, said the decline is attributed to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Total sales in 2020, including domestic and export sales, amounted to R18.9-billion – dropping from R22.3-billion in 2019. The sector employed just over 19,000 people in 2020.

Although the Minerals Council does not have figures indicating how much is lost due to illegal mining in South Africa, Seccombe said the sector as a whole loses about R7-billion annually on account of illegal mining. Commenting on the costs of illegal mining, Seccombe said chrome miners have to spend significantly more on security expenditure.

“For example, the item ‘professional services’ which includes security expenditure increased significantly between 2012 and 2013 (R59.7-million to R88.5-million, respectively),” he said.

Since then, Seccombe said, these costs have remained above R100-million per annum (except for 2018 = R97.5 million), and this is the period that coincided with an increase in illegal mining activity in the chrome industry.

“The Minerals Council is working closely with the South African police to combat illegal mining. As regards illegal chrome mining, this is a matter for the police and DMRE,” he said.

Bushveld Complex: The Ga-Mampa community is embroiled in a battle against Sefateng Chrome Mine, an opencast mining operation owned by Corridor Mining Resources. Photo: Mahlogonolo Mampa

Community woes

Zooming into the chrome map’s data shows a strip of informal, illegal and small-scale operations stretching along the R37 national road in the Limpopo province for about 60km. The 65 operations in the northern parts of the eastern limb of the Bushveld Complex stretch from the villages of Bogalatladi to Mokgorwane and include operations within Ga-Mampa village.

Although the area has been infiltrated by illegal mining, communities where legal mines are operating also have their own struggles.

The Ga-Mampa community in Limpopo is currently involved in a battle against Sefateng Chrome Mine, an opencast mining operation owned by Corridor Mining Resources, a subsidiary of the Limpopo Economic Development Agency, Bolepu Holdings and communities of Ga-Pasha, Jipeng and Ga-Mampa which have a joint 5% stake in the mine.

The community of Ga-Mampa has been involved in protests against the mine over the past two months, spending days and nights blocking trucks carrying stockpiles of chrome resources from leaving the mine. Disgruntled community members are frustrated by what they say are empty promises by the mining company, which is now looking to exploit underground chrome resources in the area.

The community members says that in the past they have not been made aware of the mine’s financial statements and who is getting what from the company even though they are shareholders. They also claim that no dividends were ever received from the mine even though there had been an agreement signed that the host community would receive a monthly payout from the mine during its operation.

According to the community members, the only beneficiaries are those selected as community representatives who also allegedly receive monthly allowances as directors of the company and senior traditional leaders (chiefs) from neighbouring tribal authorities who are not leaders of the Ga-Mampa community itself.

Questions sent to the DMRE regarding Sefateng Chrome Mine’s authorisation to mine as well as its agreement with the Ga-Mampa community had not received a response by the time of publishing. The department had also not responded to an earlier inquiry sent to them about illegal mining in the Bushveld Complex and the compliance of mining companies with social and labour plans or other beneficial agreements entered into with the mine host communities.

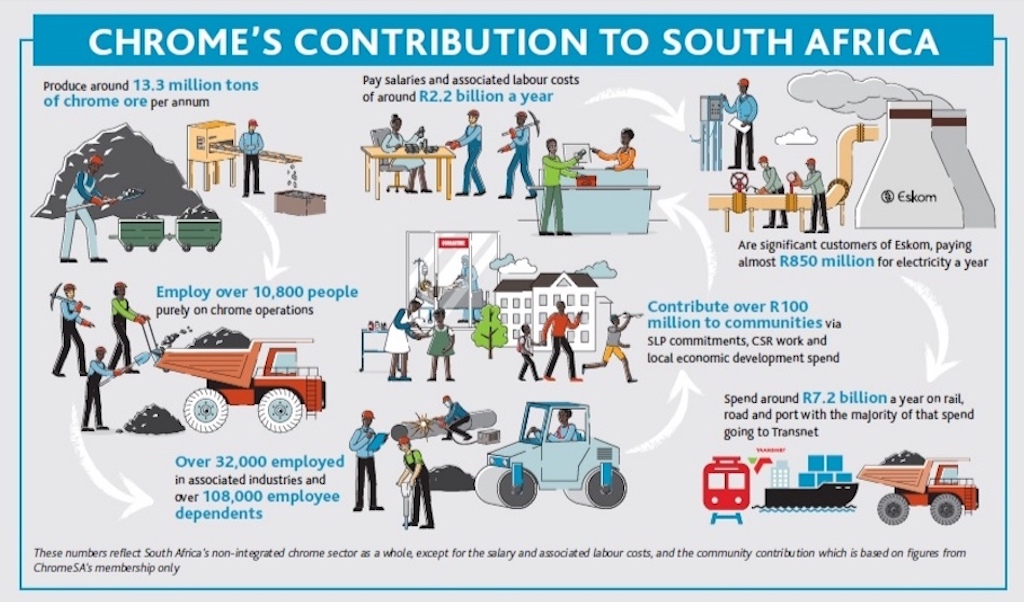

Industry leaders: ChromeSA is a group made up of the country’s top eight chrome and platinum group metals mining companies who are opposing the proposed chrome ore tax. Infographic © ChromeSA

Chrome ore tax

The creators of the AmaranthCX chrome map, which Miller says is “a stark representation of an illegal industry happening in full view”, believe the data could be of use to industry participants in the current debate around a chrome ore tax as it would be unfair to impose a tax on the legal operations while the illegal sector remains unchecked.

In October 2020 the government proposed a chrome ore tax to be levied on chrome ore exports. Business Day recently reported that the proposal was intended to “offer a lifeline to the ferrochrome industry, a sector whose international competitiveness has severely deteriorated over the past 15 years due to primarily steep increases in electricity prices”, and to retain mineral resources domestically for further beneficiation.

#MineAlert requested an interview with ChromeSA, an independent chrome ore producers group representing primary and UG2 (low-grade chrome ore) chrome ore producers that sells the bulk of their production for export. Chairperson of the group, Alistair McAdam, responded that the #MineAlert article’s areas of interest – illegal mining and the systemic failures of the DMRE – are not what ChromeSA is involved in, as the group was formed purely in response to the prospect of a chrome ore export tax.

The group, which produces 13-million tons of chrome ore a year and employs more than 10,000 people, has voiced resistance to the proposed chrome ore tax, stating that should the tax proceed, “South Africa’s chrome ore exports will become less competitive globally, leading to a loss of a significant share of the global chrome ore market.

“While the benefits of the proposed tax are entirely speculative, the cost that would be imposed on nonintegrated chrome ore producers is certain, direct and will have significant negative output and employment impacts,” said the group in a media statement in November 2020.

This #MineAlert investigation was produced with support from Oxpeckers Investigative Environmental Journalism and Code for Africa’s WanaData project.

Find the data set of chrome mining activities in the Bushveld Complex in our Get The Data repository.