15 Feb Is coal really on its way out in South Africa?

Andiswa Matikinca investigates whether the sun is setting on South Africa’s coal industry as major producers are pulling out and leaving their coal assets to be picked up by smaller companies

Mpumalanga’s coal fields: ‘The result of major producers selling their coal assets is that the enormous environmental damage of the mines is left to smaller, less-resourced companies after much of the profitable reserve has been pulled out.’ Photo © Daylin Paul/courtesy Life After Coal

South Africa’s formerly thriving coal sector has had a noticeable decline in net investments over recent years with statistics from the Minerals Council of South Africa reporting a R2-billion drop from 2010 to 2018.

As the future of the South African coal industry remains bleak and divestment from coal mining continues around the world, some of South Africa’s giant coal miners have sold or are in the process of selling their operations.

Challenges facing the coal industry include an altered customer base for the country’s coal exports as developed countries are moving towards renewable energy resources. There is a hostile funding environment for coal projects as financial institutions nationally and internationally are no longer investing in coal projects due to the pressure from environmental lobbying – a challenge too for newer coal miners with less financial muscle compared to major coal producers.

Litigation against some major coal developments is also setting a precedent for the future of investments in coal projects. In November 2020 the High Court in Pretoria set aside the environmental approval for the proposed 1200MW Thabametsi coal-fired power plant outside Lephalale in Limpopo because the minister of environmental affairs had failed to take into account the climate change impacts of the proposed coal-fired power station.

“The shelving of Thabametsi means that 136,1-million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent greenhouse gas emissions will never enter the atmosphere; and 720,000 cubic metres of precious water per annum, for 30 years, have been saved – a crucial win in a highly water-scarce region of a water-scarce country forecast to be particularly hard hit as the climate crisis intensifies,” said Nicole Loser, attorney and programme head for pollution and climate change at the Centre for Environmental Rights (CER).

“Significant air pollution that would have harmed the lives and health of residents of Lephalale and surrounds – already affected by Eskom’s Medupi and Matimba power plants – has been avoided.”

Speaking at the 2021 virtual Investing in African Mining Indaba earlier in February, the chief executive of one of the country’s top five coal producers announced that his company would no longer be investing in its thermal coal assets.

Exxaro Resources’ move from thermal coal forms part of its transition to becoming carbon neutral by 2050, said Mxolisi Mgojo. The company will continue to supply thermal coal to Eskom’s Medupi and Matimba power stations in line with existing supply contracts.

“We understand that we are a fossil fuel company and we are migrating to a whole new sustainable development goal where we intend to drive the renewable part of the future, [while simultaneously] managing the balance between the current environment and the communities we operate in,” said Mgojo, as quoted in Mining Weekly.

Duvha power station near Emalahleni: Eskom’s strategy is to procure coal for the life of its power stations, or the life of coal-mining reserves. Photo © Mujahid Safodien/courtesy Life After Coal

Energy mix

Even with the declining coal sector, the government remains intent on keeping coal as a major part of the country’s energy mix, and well into the future.

According to Eskom, one of the core pillars of its coal strategy is to procure coal for the life of Eskom’s power stations, or the life of the coal-mining reserves. In response to questions on what the future holds for Eskom’s coal-fired power stations, the company’s media desk replied that “coal requirements are underpinned by the anticipated demand and Integrated Resource Plan (IRP) assumptions into the future”.

The IRP is a long-term electricity capacity plan which provides the country with a “living plan” of its envisaged energy mix up to 2030.

In response to questions about the transition towards a clean and sustainable energy supply, Eskom responded: “Eskom is embarking on a just energy transition plan which seeks to map out a pathway to decarbonising the grid, shifting to cleaner energy solutions and ensuring concomitant increase in sustainable jobs. We are in the process of detailing this plan with the respect to technology options, financing options and socio-economic development options.

“From a coal perspective, improving the quality of coal procured to acceptable levels could potentially assist with current emissions regulations as we transition towards a cleaner and more sustainable energy supply,” said the entity’s media desk.

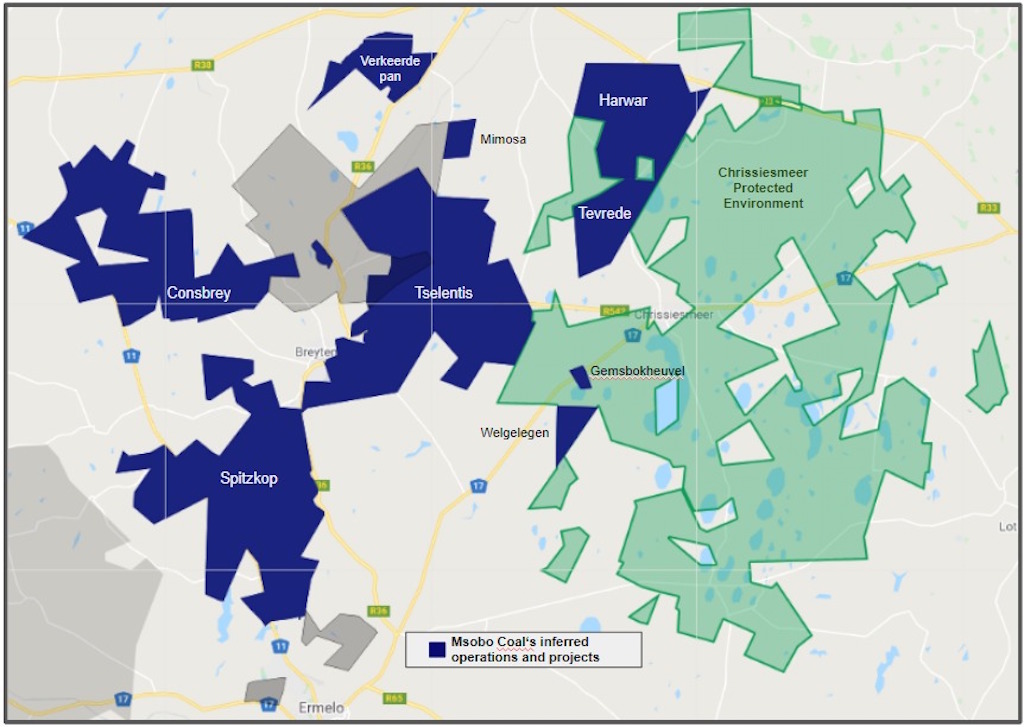

New order: Among the 82 new coal projects in exploration, feasibility study and/or construction phase in Mpumalanga are several in and around the Chrissiesmeer Protected Area. Map courtesy AmaranthCX

Smaller coal operations

Divestment by the larger companies has resulted in coal mines being taken over by smaller operators and some big companies that are not listed on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange.

One of Mgojo’s concerns about the disposal of coal assets by the major coal producers is that they could land in the hands of companies that may not comply with environmental, social and governance (ESG) requirements.

“A big concern [when] disposing of one’s coal assets [is that] they may land in the hands of parties who may not want to act responsibly in terms of how they treat the environment and other aspects of ESG,” Mgojo was quoted saying on the Argus website.

Paul Miller, director of mining supply consultancy AmaranthCX, echoes Mgojo’s concerns: “This is yet another blow to transparency within the sector as listed companies had stricter environmental, social and governance reporting and disclosure requirements,” he said.

According to Miller, the lack of proper follow-ups on the smaller operators opens up the possibility for them to get away with not doing due diligence on basic environmental impact assessments and consultation processes with interested and affected parties.

An example of this was the application by Manzolwandle Investments to mine coal near the southern border of the Kruger National Park. Despite backlash from the surrounding communities, the small company was confident about its application being successful.

Manzolwandle initially failed to follow proper consultation processes and failed to notify all interested and affected parties about some public meetings held to discuss their proposed mining project. Its environmental consultants landed in hot water when it was discovered their background information document had been copied and pasted from other similar documents.

The application was rejected by the Department of Mineral Resources and Energy (DMRE) in October 2020. Reasons for the rejection included that “the activity will conflict with the general objectives of the Integrated Environmental Management laid down in Chapter 5 of the National Environmental Management Act and that any potential detrimental environmental impacts resulting from the activities cannot be mitigated to acceptable levels”.

Speaking to #MineAlert about this application in September 2020, the attorney for the communities objecting to the application, Richard Spoor, said there was a growing trend of DMRE awarding prospecting rights and mining permits to small entrepreneurs, especially around the Mpumalanga region.

Attorney and programme head of mining at CER, Catherine Horsfield, cautions that “when one has regard to the fact that coal assets are rapidly becoming stranded assets, one cannot avoid the inference that selling these assets is more akin to dumping them, and buyers should beware”.

According to Horsfield, the result of major coal producers selling their coal assets is that the enormous environmental damage of the coal mines is left to these smaller, less-resourced companies after much of the profitable reserve has been pulled out.

In response to questions on how they would ensure compliance, the DMRE responded: “When a company sells its mining rights or changes a control in a listed entity, the cessionary (buyer) must demonstrate the technical and financial ability that they will be able to carry through the mining operations and comply with the compliance requirements of the existing mining right.”

Horsfield remarked that it is crucial “the financial provision needed for environmental rehabilitation is accurately assessed and properly collected by the DMRE. That financial provision needs to be set aside and ring-fenced before profits are paid out to shareholders.”

Coal data

Miller’s company recently mapped out 271 coal mines and prospecting operations across South Africa. His data shows there are currently 112 new coal projects in exploration, feasibility study and/or construction phase. Of these new projects, 82 are in Mpumalanga province, which is already heavily polluted due to mining and coal power stations.

According to the Global Energy Monitor (GEM), there are 23 new mines currently under development in South Africa, an additional four mines undergoing expansions, and one being recommissioned after a period of care and maintenance.

“If all of these projects were to go into operation as planned, they would add 128-million tonnes to South Africa’s output, a 51% increase in current production,” said GEM energy analyst Ryan Driskell Tate.

The DMRE hosts an online directory of operating mines that shares brief details such as the mine code, owner, name and commodity type. The site also hosts the South African Mineral Resources Administration System (SAMRAD), the official administration system of mining applications and permits. However, recent attempts to access the portal proved fruitless, and calls to the number provided for the SAMRAD help desk rang unanswered.

Miller said the DMRE portals do not make information on new prospecting applications and new coal projects owned by small operators publicly available. None of the new coal projects which are in their exploration and studies phase that he mapped out for AmaranthCX appear on the DMRE’s Operating Mines Directory and because of the login issues with the SAMRAD system these could not be verified on it.

“It has become apparent that there are deep systematic issues with the SAMRAD system,” said Miller. “There is no one-stop-shop for information, and that is a general issue of [lack of] transparency.”

In response to questions from #MineAlert about the inaccessibility of SAMRAD, the DMRE’s media desk responded that the system is available during working hours and is updated quarterly.

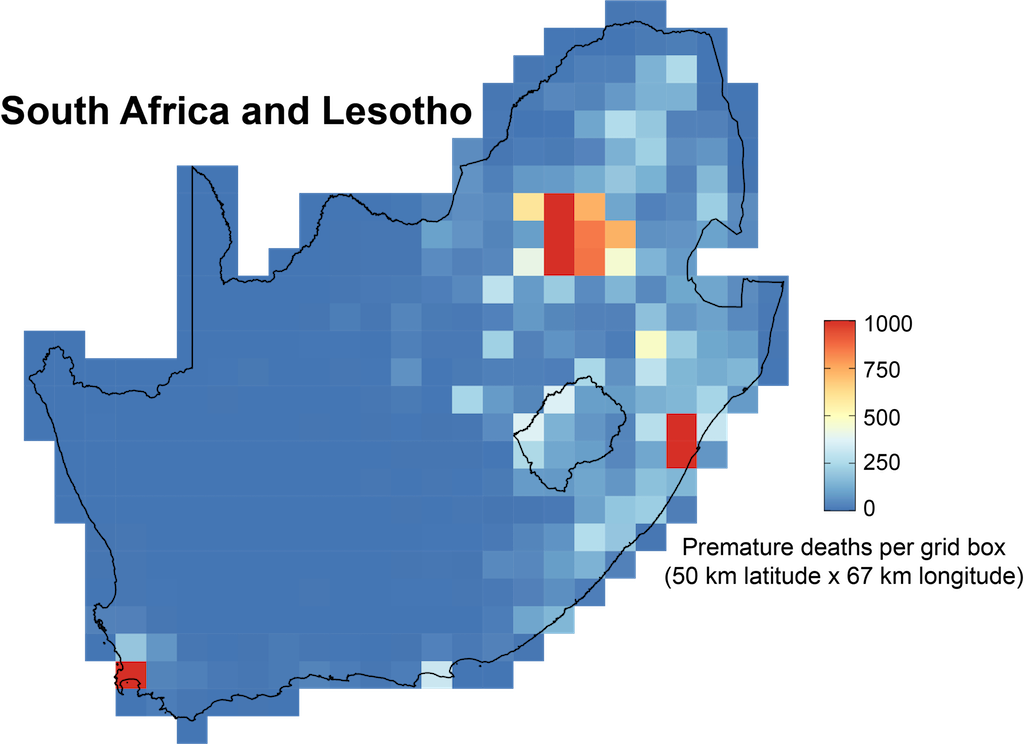

Pollution hotspot: Recent research found that in South Africa 9.3% of deaths can be attributed to air pollution from fossil fuels – about 45,134 people each year. Graphic supplied

Life after coal

Life After Coal/Impilo Ngaphandle Kwamalahle, a joint campaign of civil organisations committed to discouraging the development of new coal-fired power stations and mines; reduce emissions from existing coal infrastructure and encourage a coal phase-out; and enable a just transition to sustainable energy systems has had some notable successes towards these objectives.

Some milestones in the past year include the criminal prosecution of Eskom for violating permit limits and filing misleading information to authorities at its Kendal coal power station; and the proposed Thabametsi coal plant being set aside (following successful litigation by the campaign), with the proposed Khanyisa coal plant in Mpumalanga likely to follow.

“These victories have resulted in tangible benefits for health, climate, the economy and the environment,” said Loser.

A new study published this week by scientists at Harvard University, University College London and other universities found that air pollution from fossil fuel use is responsible for one in five deaths worldwide. This research found that in South Africa, 9.3% of deaths can be attributed to air pollution from fossil fuels – about 45,134 people each year.

“Coal is not on the way out, but we have certainly seen positive indications of a declining coal sector in South Africa,” Loser said. “Examples include the withdrawing by investors and financiers from proposed coal power projects, the adoption of policies by commercial lenders to restrict funding of coal projects, and diminishing allocations in South Africa’s electricity mix to coal power.”

This #MineAlert investigation was produced with support from Oxpeckers Investigative Environmental Journalism and Code for Africa’s WanaData project

Data points from The map they don’t want you to see by AmaranthCX are now included on #MineAlert, the Oxpeckers geo-mapping tool used to track and share information on mining licences. The data set is also available on our Get The Data repository.