15 May The need for speed in water licensing

The government is in the process of fast-tracking water use authorisations. What are the implications for water security? Andiswa Matikinca investigates the data

Water shed: The Drakensberg mountain range is home to five of the 21 identified SWSAs. Photo: Yuexuan Chen

The current time frame involved in the processing of a water use licence application in South Africa can take up to 300 days, depending on the complexity of the application.

At this year’s State of the Nation address in February, President Cyril Ramaphosa announced that water use licences would now be issued within 90 days – less than a third of the time under the current regulations of the National Water Act published on March 24 2017.

“Following the announcement by the president, the department has started revising the regulations to change the process accordingly,” said Department of Water and Sanitation (DWS) spokesperson Sputnik Ratau.

One of the first steps the department has taken is augmenting its internal capacity in order to meet the reduced time frames. The 90 days’ framework can be expected to be implemented as soon as the regulations are announced – “the intention of the department is to publish the revised regulation in the 2020/21 financial year”, said Ratau.

The standard water use licence document includes details of the entity that grants the licence, details of the applicant, properties the application or licence covers, water uses applied for, a description of these activities, general conditions of the licence, and how to appeal the granting of the licence.

In March 2018 the department migrated to an online system for processing water use licence applications. The Electronic Water Use Licence Application and Authorisation System (e-WULAAS) portal’s main objectives include providing the department’s authorisation staff with a web-based platform to “manage, coordinate, track and finalise the authorisation processes of registered water uses, culminating in the issuing of a water use licence”.

Ratau said although the e-WULAAS online system is in its infancy, it has simplified the application process by improving record keeping, and easing communication and movement of documents between the applicants, regional offices and head office.

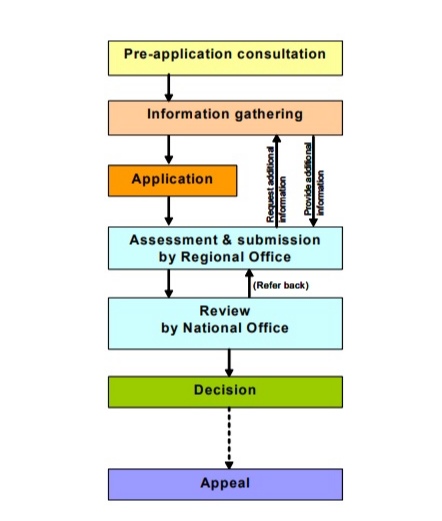

The six-step process, according to the DWS Internal Guideline: Generic Water Use Authorisation Application Process

Application process

The six-step online application process is broken up into three phases: application initiation, screening, and processing and finalisation.

Prior to applying for a water use licence, applicants are encouraged to contact the Department of Environmental Affairs as part of the pre-application process to find out whether the proposed project requires an environmental impact assessment (EIA).

Considerations include a description of the proposed development and associated infrastructure, property details of the proposed development, amount of treated water that will be produced per day, any indigenous vegetation that may need to be cleared to accommodate the proposed development, and whether there is existing access to the site.

During the pre-application phase, applicants are also required to request further input and participation from interested and affected parties (I&APs) such as non-governmental organisations, as well as other relevant external stakeholders including people living in and around the area of the proposed water use.

A risk assessment should be performed during the pre-application process by a departmental official in order to determine the hazard class of the proposed activity. The risk assessment is based on two criteria: the potential impact of the activity on the resource, and the sensitivity of the water resource in the vicinity of the proposed water use activity. The outcome of the risk assessment dictates the appropriate mechanisms required to regulate the water use.

Criteria used as guidelines when evaluating an application include the strategic importance of an application, stressed catchment areas and resource availability. No licence may be granted in stressed catchments where there is no further water available for allocation; in areas where no water reserve has been determined; if the approval of the licence may impact in an unacceptable manner on any other water user; and in the case where the proposed activity is in conflict with land development.

Water use licences granted for mining activities are concentrated in Mpumalanga, heart of the country’s coal fields. Photo courtesy CER

Compliance monitoring

Leanne Govindsamy, a lawyer at the Centre for Environmental Rights, said the intention behind the president’s statement and the implications of speeding up the application process need to be interrogated.

A 2019 report by the centre detailed non-compliance in water use by mining companies located in Mpumalanga province. It highlighted how the inability to issue water use licences within a reasonable amount of time, licences being issued with inappropriate conditions and inadequate monitoring requirements, and slow processing of licence amendment applications were some of the reasons licence holders were able to get away with non-compliance.

“The lengthy time period holds back certain mining operations because a water use licence is a requirement for a mining permit, and we are aware of how the time period negatively affects companies,” she said. “If that is purely the intention [behind speeding up the process], then we have got to question what the implications of that will be.”

Ratau said the department has two processes for monitoring compliance with the conditions of a water use licence. The first is that the licence directs the licensee to undertake monitoring and send reports to the department at specified intervals. These reports are processed by the department’s officials and necessary corrective measures are taken if necessary.

The second way of ensuring compliance is that the department undertakes inspections to audit compliance with licence conditions. An audit report will be issued with clear recommendations for corrective measures, if necessary.

“As a guarantee that strategic water source areas (SWSAs) will not be shortchanged by the new regulated process, Section 27(1) of the National Water Act will still be applied with the reduced turnaround time,” said Ratau.

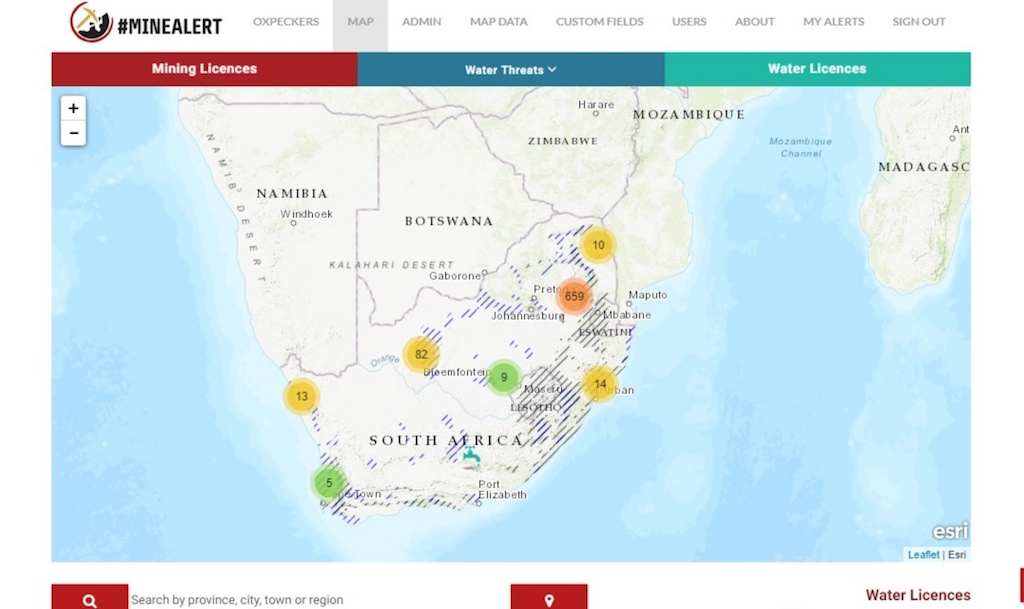

Mining your Water: The Water Licences map currently has more than 700 data points of water use licences approved for mining

Licence data

#MineAlert, the digital tool that helps users to track and share information on mining licences across South Africa, includes a Mining your Water map layer that shares information on more than 790 water use licences granted to mining companies and that identifies strategic water zones affected by these licences.

Data sourced from the Department of Water and Sanitation following requests by #MineAlert under the Promotion of Access to Information Act shows there are water use licences approved for mining across eight of South Africa’s nine provinces. According to the data provided by the department, the Eastern Cape remains the only province without water use licences for mining activities.

Asked why operating mines in the Eastern Cape do not appear to have been issued with water use licences, Ratau said the water department “depends on the public with regards to economic sectors of applications submitted. If the data shows that in Eastern Cape there are no mining applications, it implies that people in Eastern Cape do not practise mining activities that trigger water uses.”

Water use licences granted for mining activities are concentrated in Mpumalanga (399 licences) and Limpopo (96). Other provinces with a large number of licences include the Northern Cape (91), North West (80) and Gauteng (59). The commodities mostly being mined in these provinces are coal, platinum, diamonds, chrome and gold.

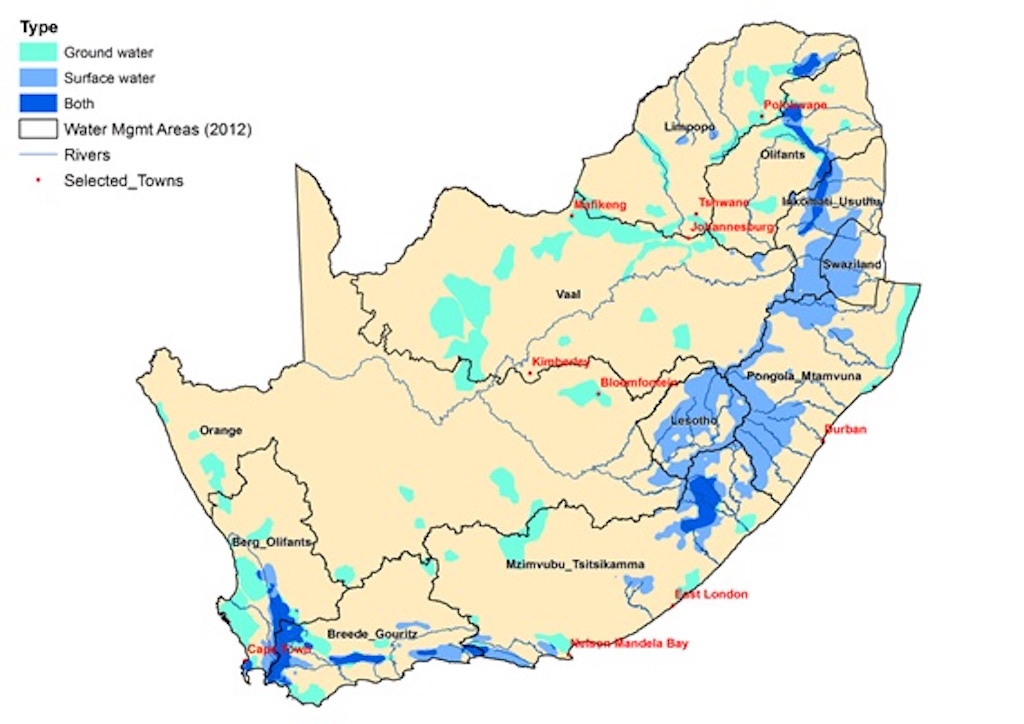

Protective measures: The introduction of strategic water source areas by the DWS is one of the measures taken to identify and protect South Africa’s water sources

Graphic courtesy CSIR

Strategic water source areas

Strategic water source areas (SWSAs) are South Africa’s “water factories” – they supply 50% of the population with water, 64% of the economy and about 70% of the water that is used by agriculture. A total of 21 SWSAs have been identified and only 11% of them receive formal protection.

Analysis of the data collated by #MineAlert shows the National Freshwater Priority Area most affected is the Upper Olifants catchment in Mpumalanga, which is the most mined province in the country.

Groundwater priority areas in the arid Northern Cape, which provide drinking water and irrigation, are also subject to licence approvals. The data shows at least 20 licences occur in the areas surrounding Kuruman, Kgatelopele and Postmasburg – the third largest number of water use licences granted in the province.

The Harts River, which is a tributary of the Vaal River and has a greater part of its basin based in the Northern Cape, runs adjacent to these towns. A large increase in the number of licences issued in the area was recorded between 2015 and 2019.

In North West Province, the data also shows an increase in issued water use licences specifically in areas close to the Elands River, a tributary of the Crocodile River and part of the Limpopo River. Licences issued went from one in 2001 to a total of 30 issued licences between 2010 and 2019.

Governance issues: ‘The current minister could be attempting to address the backlog of applications in good faith.’ Photo: Mark Olalde

Political economy

Sharon Pollard, executive director of the Association for Water and Rural Development, said frequent refusals of water use licence applications in the past might have been a stumbling block for the political economy of water, which includes approving water use for mining projects. This resulted in a need to centralise the processing of applications.

Delays in the past were caused by a number of reasons, including a shortage of good governance structures and the lack of an integrated system to empower DWS staff members at sub-catchment level to assess proposed water use licence applications against other activities in a catchment area. These observations were made from the training and capacity development of DWS staff over the years, she said.

“The department didn’t have the tools to quickly approve and issue water use licences under its former minister, and the current minister could be attempting to address the backlog of applications in good faith. There is also a possibility that the Presidency is understanding this as a clear and simple process to speed up water use licensing as mining is one way to get people employed,” she said.

For this process to be successful, Pollard advised that more water catchment management agencies should be established, and proper tools be put in place to build capacity within the department.

She emphasised the need for good governance issues within the DWS to be sorted out, especially when it comes to decentralising water governance. “We keep doing more planning and more planning, but the implementations are weak,” she said, referring to the existing protective measures for water resources that include the introduction of strategic water source areas.

She recommended a clear mechanism of decentralisation of governance, which would include catchment forums operating at a lower level that could contribute to catchment management agencies. This, according to Pollard, is a system that has proved to be quite functional with the Inkomati-Usuthu Catchment Management Agency – which supplied almost 60% of the data currently on the Mining your Water map.

This investigation is part of the Mining your Water series, supported by the Open Society Foundation for South Africa.

- Use the #MineAlert tool to track mining and water use licences across South Africa