19 Feb Too low, too slow: SA’s rhino convictions

The real war on poaching happens in the courtroom – but the wheels of justice grind slowly in many rhino-related cases, writes Jacqueline Cochrane

White rhinos: Without fail, collaboration is mentioned when insiders are asked how rhino poaching and other forms of wildlife crime can be stopped. Photo: Jacqueline Cochrane

It’s a cold and bright day in Vienna, but the windowless conference room at the United Nations centre is packed to the brim and stuffy. Side events at big UN conferences don’t usually see a high turnout, yet it’s a full house for the launch on October 17 2018 of a new guide for countries to draft legislation on wildlife crime.

Kevin Pretorius, an attorney from KwaZulu-Natal, has chosen to present a case study that he often uses when training prosecutors and rangers. “This content is disturbing,” he warns, before clicking to a series of crime-scene slides from a poaching incident that took place in the iSimangaliso Wetland Park in July 2013.

For the South Africans in the audience, there is a sickening familiarity to the images showing the carcass of a white rhino, a bloodied, messy pulp between her eyes where the horns had been hacked off. Like many other rhinos that have been poached, this was a pregnant female. Her spinal cord had been cut. It is not unusual for horns to be removed while the animal is still alive.

The butchering of the rhino marked the first tragedy in this case study. A second would unfold 20km away at the Mtubatuba Magistrate’s Court where, despite a confession that appeared to be water-tight, the three people accused in the case walked free.

The rangers who’d heard the gunshots had worked bravely through the night. With the odds of a difficult terrain and narrow window of time stacked against them, they’d managed to track down the perpetrators.

Poachers work quickly to hide the horns and tools used to harvest horn, but the rangers were able to find where they had hidden a high-calibre firearm, ammunition and an axe still covered in blood. They also found wet clothing that the accused had worn while crossing a river, as well as the horns: one weighing 4.2kg, and the smaller, back horn weighing 2.5kg.

The rangers handed the crime scene and suspects over to police. When the accused confessed their crimes to the police – including the illegal killing of the rhino – everyone thought the wheels of justice would turn smoothly. A court docket was opened against Sakhile Shabangu and two others – accused one and two were described as South African citizens, accused three as a Mozambican citizen – and the three were charged on November 18 2013. (Search “Shabangu” to find the case on the Oxpeckers RhinoCourtCases tool).

Pretorius recounts the details of the case: “The police were so happy about the confession that no forensics were done. There was no DNA linking the accused to the firearm, and no fingerprints linking them to the firearm and the axe. There was a confession, but nothing to fall back on – the accused were not found in physical possession of the horns, rifle or axe.

“There was a photograph that allegedly showed that one of the suspects who had confessed had been assaulted – this according to the defence lawyer. There was some blood on the person’s ear. In the trial-within-a-trial, the confession was found to be inadmissible evidence. And there was nothing else linking the accused to the firearm and the axe.”

On April 24 2015 Shabangu and his co-accused were acquitted in terms of section 174 of the Criminal Procedure Act. The same firearm linked to their case had been linked to 10 other rhinos that had been killed, Pretorius said.

Before practising as a specialist criminal and environmental law attorney, Pretorius had frequently prosecuted these types of offences as a senior prosecutor. He later founded the GreenLaw Foundation, a non-profit that builds skills and knowledge “from crime scene to courtroom” to prevent mistakes like those in the Sakhile Shabangu case.

Substantial delays: File photo of Dawie Groenewald, member of the ‘Musina Mafia’ syndicate that faces more than 1,870 charges. Arrested in 2010, his case has been postponed numerous times and he is due to appear again on 1 March 2021. Photo sourced

Prosecuting wildlife crime

According to Willie Hofmeyr, former head of the Asset Forfeiture Unit at the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA), there has been a greater focus on prosecuting wildlife crime cases over the past four or five years.

However, he said, “still quite a lot of missionary work needs to be done” to ensure that law-enforcement agencies recognise wildlife crime as a form of transnational organised crime.

“Wildlife crime, as a form of organised crime, is a business,” Hofmeyr said. “Organised crime moves to where there is money to be made and where the risk is low, due to law enforcement being low or not treating it as a kind of organised crime. And where law enforcement tightens, it will just migrate elsewhere, where the risk is low.”

Acknowledging that rhino poaching is a form of transnational organised crime, and not just a conservation issue, is more than just semantics: it has important implications for the criminal-justice response, agreed Hofmeyr and various other legal experts interviewed.

While the act of poaching is often the most visible and most readily understood part of the problem, it is the ability for the horn to be moved beyond the protected area or farm, across provincial boundaries and national borders and all the way to the end consumer that allows for this type of crime to be not just possible, but also profitable, they agreed.

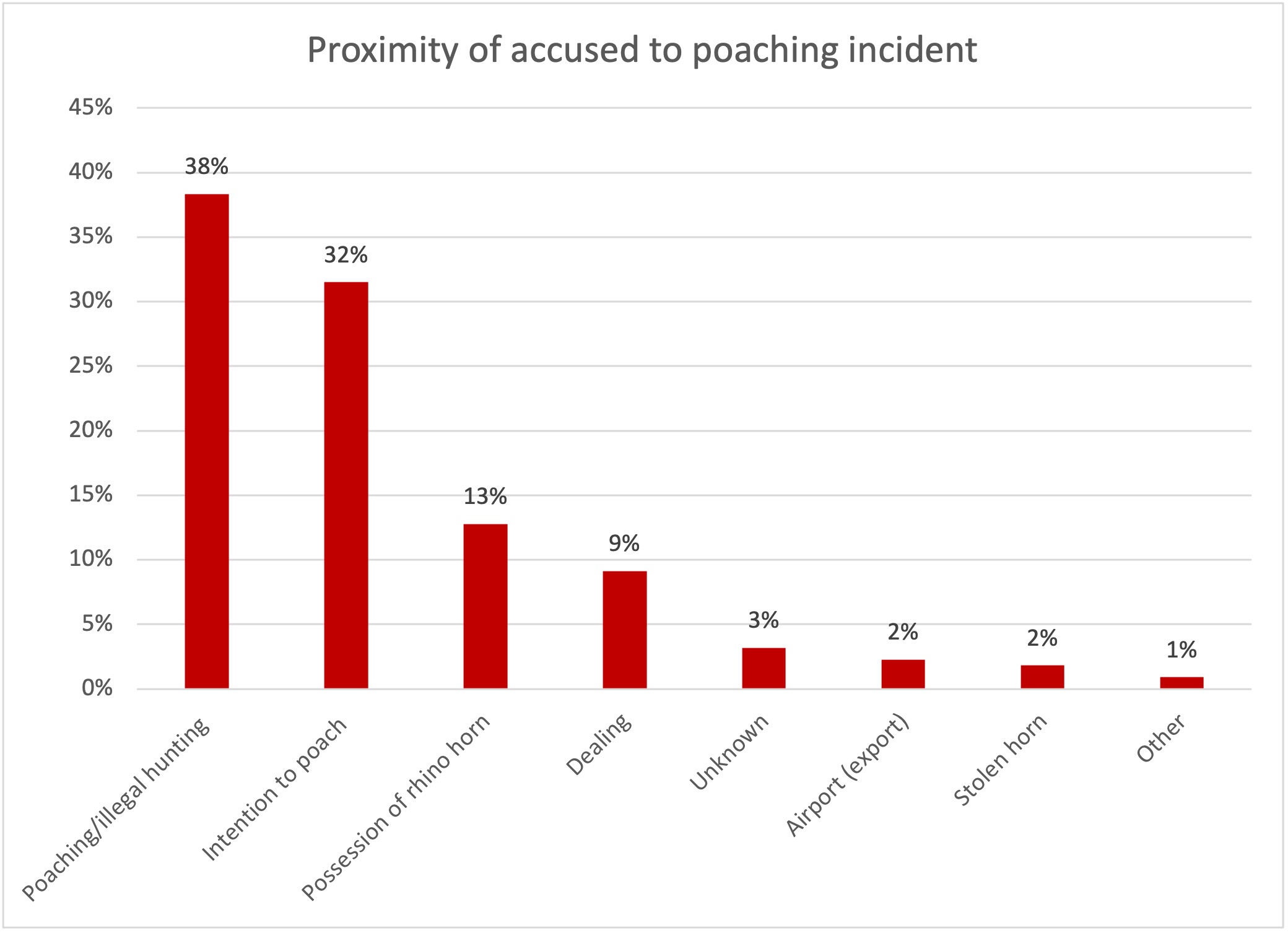

Close to home: Some 38% of the court cases relate directly to incidents where poaching occurred. Graphic: Jacqueline Cochrane

Court cases

Analysis of the data on the RhinoCourtCases tracker confirms that by far the majority of rhino-related cases that end up in court involve lower-level poachers.

Some 38% of the cases relate directly to incidents where poaching occurred. Another 32% relate to an intention to poach, often linked to possession of arms and other equipment used to poach and trespassing.

Together, these two categories reflect cases where the accused were directly involved in an act of poaching that had, or had been intended, to occur. Only 26% of cases involve charges where the horn was actively being smuggled or sold, or had already changed hands.

The data also show that cases often face substantial delays. One example is the case against alleged KwaZulu-Natal rhino poaching kingpin Dumisani Gwala, who faces 10 charges relating to the illegal purchase and possession of rhino horns‚ and of resisting arrest. His trial in KwaZulu-Natal courts has been delayed more than 20 times. (Search “Gwala” on the Oxpeckers RhinoCourtCases tool.)

Similar delays have been seen in cases involving alleged poaching kingpins Dawie Groenewald, who was first arrested in 2010, and former policeman Joseph “Big Joe” Nyalunga, who was first arrested in 2011. Since then, both Groenewald and Nyalunga have been granted bail and their cases have been postponed multiple times. Groenewald’s case has been moved to March 1 this year, and Nyalunga is expected to appear in court again on February 21.

“Most arrests are of lower-level poachers and couriers, and the challenge is how to successfully investigate and prosecute those higher in the criminal pyramid, especially when they may live in different countries,” states a 2019 report by the Convention in International Trade in Endangered Species.

“Whenever possible cases should be recognised as serious organised crimes and coordination between different government agencies improved, with police departments playing a key role.”

Robust, multi-national investigations are critical in dismantling the syndicates that source, move and sell rhino horn, agreed Ashwell Glasson, registrar at the Southern African Wildlife College.

Among those involved in combating wildlife crime, this is often expressed as an urgent call to “follow the money”, or “catch the big fish”.

“Some of these big fish are locally based. We have seen high-level syndicate members in some of the rural communities adjacent to the Kruger National Park, in KwaZulu-Natal and others in the trafficking hub in the East Rand of Johannesburg,” Glasson said.

The National Prosecuting Authority reported in its 2019/20 annual report that 41 verdicts involving 59 accused had been obtained in rhino-related cases. In February 2021 the Constitutional Court overturned a controversial application for cases before the Skukuza Regional Court, where many rhino poaching cases are tried, to be moved to the Mhala Circuit Court.

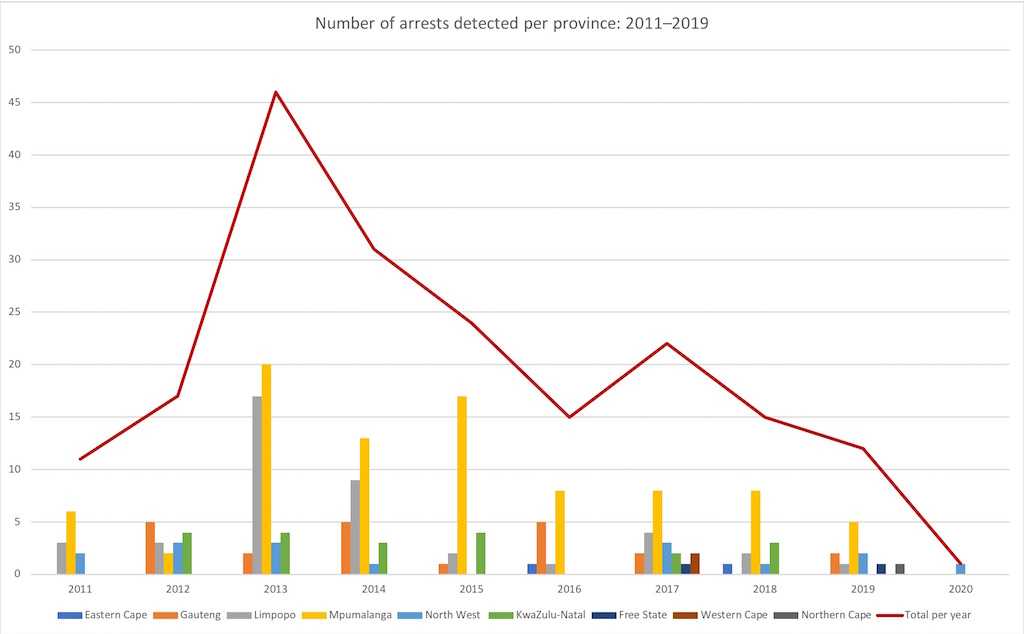

On hold: The strict lockdown in 2020 disrupted syndicate logistics, but recent arrests indicate they were stockpiling horns. PoachTracker provides instant access to data on rhino deaths and poaching incidents since 2010. Graphic: Jacqueline Cochrane

Covid-19

While the Covid-19 pandemic has reportedly been linked to a decrease in poaching figures, it is expected to have a negative impact on court cases.

Glasson said the strict lockdown in South Africa in 2020 had disrupted syndicate logistics – “specifically in the slowdown of poaching events and the transportation of rhino horn. However, recent arrests of local syndicate members in the East Rand trafficking hub have also demonstrated fairly sophisticated behaviour in stockpiling horn.”

The full effects of the pandemic on law-enforcement efforts are still to be seen: “Police officials have had their hands full with ensuring Covid compliance, from checkpoints to supporting Department of Health vetting and more,” said Glasson.

A wildlife investigations trainer who asked not be named because of the sensitive nature of his work said in many courts a number of cases have been remanded for long periods due to Covid.

“Theoretically this should not mean that the rhino cases will fall through the cracks, but with any long remands the witnesses become unavailable and the accused have a greater possibility of being released on bail as [the Department of] Correctional Services strives to reduce numbers in jail.” The backlog at courts means that less important cases are likely to be struck off the role at the slightest hint of a delay by the state, he said.

Skukuza Court: In February 2021 the Constitutional Court overturned a controversial application for cases before the Skukuza Regional Court, where many rhino poaching cases are tried, to be moved to the Mhala Circuit Court. Photo courtesy Stroop

Collaboration

Without fail, collaboration is mentioned when insiders are asked how rhino poaching and other forms of wildlife crime can be stopped.

Many experts said different national law-enforcement agencies work in a siloed, territorial way. They described how the most successful prosecutions are often the result of informal inter-agency collaborations based on strong relationships between individuals.

Alastair Nelson, senior analyst with the Global Initiative against Transnational Organised Crime and the managing director of Conservation Synergies, explained that similar dynamics play out at a multilateral level, where collaboration is crucial to build cases between supply countries like South Africa, where rhinos are poached, and demand centres – typically in Asia – where the final products are sold to consumers on the black market.

China, a key market for illicit wildlife products, has shown increased will to prosecute wildlife crime, both domestically following the outbreak of Covid-19 and in effective collaborations with countries like Nigeria.

Nelson said agencies such as China’s Custom’s Anti-Smuggling Bureau have been mandated and resourced by its government to help facilitate multi-national investigations, and that South African authorities would be wise to leverage this.

This investigation was supported by Wits Journalism and the African Investigative Journalism Conference

- Track these and other court cases on the Oxpeckers Rhino Court Cases tool