14 Feb Inside the global conservation organisation infiltrated by trophy hunters

Indepth investigation by Roberto Jurkschat shows trophy hunters and luxury fashion brands have been working for years to influence the IUCN, the world’s leading authority on science and endangered species conservation

Fred Bercovitch (left): One of the most renowned giraffe experts in the world and a member of the IUCN specialist group on giraffes and okapis. Photo: supplied

Geneva – Giraffes may well tower over all other animals in the natural world — but in the wild, their numbers are rapidly dwindling, and they are desperately in need of protection. The giraffe population in Africa has collapsed by 40% over the last three decades, with climate change and agricultural expansion the main factors.

In 2018, six African countries — the Central African Republic, Chad, Kenya, Mali, Niger, and Senegal — joined together to sound the alarm about this stark decline. They believed there was another threat the animals faced: the international trade in giraffe trophies and body parts.

You can, after all, buy giraffe heads as decorations for your home for around $9,000 online, or pay for a craftsperson to stretch the animals’ skin into custom furniture. Giraffe brains are used to make medicine, sold in some African countries as supposed remedies for AIDS.

Representatives from the six African countries turned to a body they hoped would support their goals: the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), one of the world’s largest and most influential conservation organisations.

They requested a scientific analysis of the situation from the IUCN, knowing a favourable expert opinion would greatly improve the chances of success of a joint motion to help protect giraffes from trophy hunters that they planned to submit to the organisers of the United Nation’s World Wildlife Conference.

But several months later, the IUCN concluded that international trade in giraffe trophies did not present a decisive threat to the species.

The IUCN is widely recognised as the global leader on species conservation. Its huge network of 15,000 experts advise national governments on what endangered species deserve protection, and its headline-grabbing Red List, published between every five and 10 years, is the world’s most comprehensive account of which species are most at risk of extinction.

But investigation showed that trophy hunters and luxury fashion brands have been working for years to influence the IUCN, to expand the billion-dollar trade in endangered animal species.

Trophy hunting is big business — in the past decade 1.7-million hunting trophies were traded worldwide, and according to the International Fund for Animal Welfare, 200,000 of those are believed to have come from endangered species.

Advocates defend trophy hunting as a way to fund conservation efforts that ultimately help the animals being hunted, even if they are already endangered. But critics say the benefits are exaggerated, and are a convenient argument to make for those people who simply want to kill wild animals for sport. Trophy hunting as an issue has been etched into the public consciousness since worldwide anger erupted over the killing of Cecil the lion in Zimbabwe, by an American dentist who had a permit.

Conflicts of interest within the IUCN have exposed the links that exist between IUCN member organisations and the trophy hunting and fashion industries. Some conservation experts have been shut out of the IUCN groups involved in the crucial decisions about which species should be classified as the most threatened.

Cecil the lion: Trophy hunting as an issue has been etched into the public consciousness since worldwide anger erupted over the killing of Cecil by an American dentist who had a permit. Photo: courtesy WildCRU

Conservation experts

This investigation canvassed opinions from conservation experts worried about the influence trophy hunters have on IUCN policies; tracked flows of money from big game hunters to organisations with links to IUCN members; heard that experts were censured for speaking out against the leather trade; learned that efforts to support the protection of animals were suppressed by the IUCN; and has seen an email sent from the account of an IUCN member asking trophy hunting lobbyists and rhino breeders to publicly support China for expanding the trade on tiger and rhino parts.

“IUCN is considered the world’s leading authority on science and species conservation, but when you look at the members who influence the organisation, you have to question whether this status is still justified,” said biologist Daniela Freyer of the German organisation Pro Wildlife.

In response to the findings, the IUCN said its member organisations were screened before admission, and were required to report potential conflicts of interest.

“The process through which IUCN policy is determined ensures that the union’s policy is not unduly influenced,” a spokesperson said. “IUCN policy is determined democratically by its over 1,300 members at World Conservation Congresses. Neither IUCN Commission members nor staff can determine IUCN policy outside of that process.”

But how can an organisation tasked with the monumental responsibility of global conservation decide which species deserve protection when some of its members have numerous links with people who pay big money to hunt some of the world’s most threatened species, and those who want to harvest skins and furs for clothing?

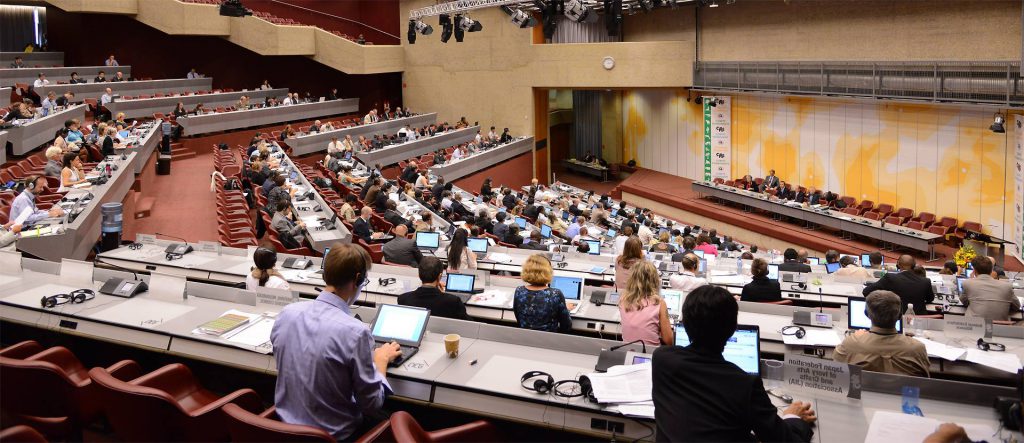

Convention rules: Delegates at the 65th CITES Standing Committee meeting in Geneva discuss strategies to protect endangered species. Photo: sourced

International treaty

Explaining exactly what role the IUCN plays in wildlife conservation worldwide is a little complicated, but it’s essential to understanding how truly influential it is.

Let’s start with one of the most prominent global conservation agreements, the 1973 Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, or CITES.

The international treaty aims to ensure that global trade in wild animals and plants does not threaten the survival of the species in the wild. Almost every country in the world has agreed to abide by the convention’s rules.

Whenever member countries want to propose stricter protections of certain animal species by getting them “uplisted” in the CITES agreement, they typically approach the IUCN for scientific analysis, and the global trade monitoring organisation known as Traffic – just like the six African countries did when they wanted to increase protection for giraffes.

Traffic is a joint programme of the IUCN and the World Wild Fund for Nature (WWF). Its website says that supporting the enforcement of CITES has been the NGO’s “ongoing priority” since it was founded in 1976, and that it works to “ensure that international trade in wildlife remains at sustainable levels”.

After the IUCN and Traffic publish their joint analyses, CITES member countries vote for or against the proposals at the CITES Conference of the Parties, also known as the World Wildlife Conference, which takes place every three years.

There are 160 specialist groups in the IUCN, each focusing on a specific species or several similar species. It is these groups that prepare the analysis that is eventually presented to the World Wildlife Conference, where countries’ representatives decide which endangered animals can be traded, and to what extent.

In an email, a spokesperson for the UN-administered CITES Secretariat, which helps run the convention, said: “Governments, inter-governmental and non-governmental organisations, stakeholders, industry, academia, etc are also free to express their opinions and disseminate information as they see fit and no ‘rules’ exist to govern such commentaries.”

The rules decided at the World Wildlife Conference have huge ramifications for trophy hunters, the global food industry, and fashion companies that buy masses of skins and furs from endangered species.

The IUCN says it has clear rules that require members to report conflicts of interest, but potential conflicts are everywhere.

Powerful lobby: Wildlife trophies adorn the headquarters of the Safari Club International in South Florida. Photo: sourced

Trophy hunters

Julian Fennessy is a 46-year-old Australian biologist, and director of an NGO called the Giraffe Conservation Foundation (GCF) based in Namibia, where he has lived for the past 20 years.

He is also the chair of the IUCN expert group for giraffes and okapis, which according to its website, “leads efforts to study giraffe, okapi and the threats they face, as well as leading and supporting conservation actions designed to ensure the survival of the two species into the future.”

The GCF makes a lot of money from trophy hunters — its own website makes no secret of the fact that they are among the NGO’s biggest sponsors. The foundation for the Dallas Safari Club, the largest hunting association in the world, has donated at least $50,000 to the GCF, as has the Ivan Carter Wildlife Conservation Alliance, whose founder Ivan Carter has repeatedly promoted trophy hunting.

Fennessy said these donations don’t impact his work for the IUCN, where he is supposed to make objective decisions about the future of giraffe populations.

“GCF has never been nor will we ever be a mouthpiece for any supporter who provides assistance in helping us achieve our mandate to save giraffes in the wild in Africa through a science-based conservation approach,” Fennessy wrote in an email.

“I in my personal capacity or as director of GCF have never received any payment to provide an IUCN recommendation of the giraffe proposal. Our views and conservation approach are science-based and this approach is applied to all aspects of our work.”

Shane Mahoney, from Canada, is the chair of the North American IUCN group on “sustainable use and livelihoods”. But he’s a big game hunter too.

He’s also a former member of the International Council for Game and Wildlife Conservation (CIC) and the Dallas Safari Club, and currently is the director of a trophy hunting lobby group called Conservation Force.

Conservation Force states on its website that Mahoney attended an IUCN meeting in 2004 to lobby for African elephants to have their status on the Red List lowered from “endangered” to “vulnerable.” On the page for his own personal pro-hunting initiative, Conservation Visions, Mahoney poses with a rifle slung over his shoulder.

The Dallas Safari Club gave financial support to Conservation Visions in 2017 and 2018. In 2017 Mahoney spoke at the hunting club’s annual meeting, where he said that the Dallas Safari Club was “the real deal” when it came to species conservation.

When contacted, Mahoney said he had never witnessed an IUCN decision being unduly influenced. “I have never witnessed, nor have I ever been approached by anyone or any organisation to try and unduly influence the decisions, policies or actions of IUCN, nor would I do so, and nor would I tolerate such behaviour,” he said via email.

Conservation Force’s president, John Jackson III, has fought several attempts to protect white rhinos, classified on the Red List as “near threatened”. According to the group’s website, Jackson has prevented stricter protections of lions and North American desert sheep, and has filed at least a dozen challenges to the US Endangered Species Act, to lower the bar for importing hunting trophies.

In an interview at the World Wildlife Conference in Geneva last summer, Jackson (73) said he has killed elephants, lions, leopards, African buffalo, and rhinos: animals that big game hunters refer to as the “big five”. He also has a stuffed polar bear at home, he said.

Tiger trade: China’s controversial move to lift a 25-year moratorium on the trade of tiger and rhino body parts was praised by a member of an IUCN expert group. Photo: Czech customs authority

Critical voices

The IUCN’s relationship with big game hunters has been a major concern for some wildlife experts for years.

“Internally, the influence of trophy hunters has long been the subject of debate within the IUCN,” said Freyer of the Pro Wildlife organisation in Munich. “The hunting associations repeatedly commission studies to be produced whenever a species comes into the focus of conservationists. In the IUCN, there are also critical voices, but they are not always welcomed.”

According to a report from the UK-based Campaign to Ban Trophy Hunting, members of the Conservation Force in the IUCN are currently concentrating on the promotion of the hunting of leopards and lions.

Lion hunting is controversial because, according to the IUCN’s own data, the number of lions in Africa shrunk by 43% between 1993 and 2014. In recent years, the trade in trophies and lion bones for traditional Chinese medicine has increased significantly. The IUCN estimates that only about 20,000 lions now live in Africa.

It’s not just the big five that conservationists worry about, however.

In 2018 China lifted a 25-year moratorium on the trade of tiger and rhino body parts, which are highly valued in traditional Chinese medicine. China’s actions were praised by Hank Jenkins, who runs a consulting company in Australia called Creative Conservation Solutions, and is also a member of the IUCN’s expert group on crocodiles.

This reporter obtained an email sent from Jenkins’s account in which recipients were asked to support the “bold decision taken by China to try a new approach to conserving tigers and rhinoceros”. The 21 people the email was sent to included the owner of one of the world’s biggest rhino farms, and other trophy hunting advocates. The email said Jenkins had been asked by an acquaintance in the Chinese government to reach out to his network.

Three days after the email was sent, Jenkins praised the Chinese government’s actions as a “ray of hope for tigers and rhinos” in an article published online.

Jenkins told this reporter he had not send the 2018 email in question, describing it as “clearly a fabrication”.

“I can assure you there is no foundation to the allegations, which I consider are defamatory and have the potential to impact adversely on my character and profession,” he said via email.

Days later, amid international outcry over the impact its decision would have on tigers and rhinos, endangered in the wild, China reversed its decision.

There are more potential conflicts of interest.

Dietrich Jelden was a department head at Germany’s Federal Agency for Nature Conservation until 2016. Since retiring, he has acted as a lobbyist for the CIC hunting association and campaigned against the protection of giraffes. He’s also still a member of the IUCN expert group on crocodiles.

In an email response, he said he had no conflict of interest, was not a trophy hunter, does not receive any money from the CIC, and acted out of conviction only.

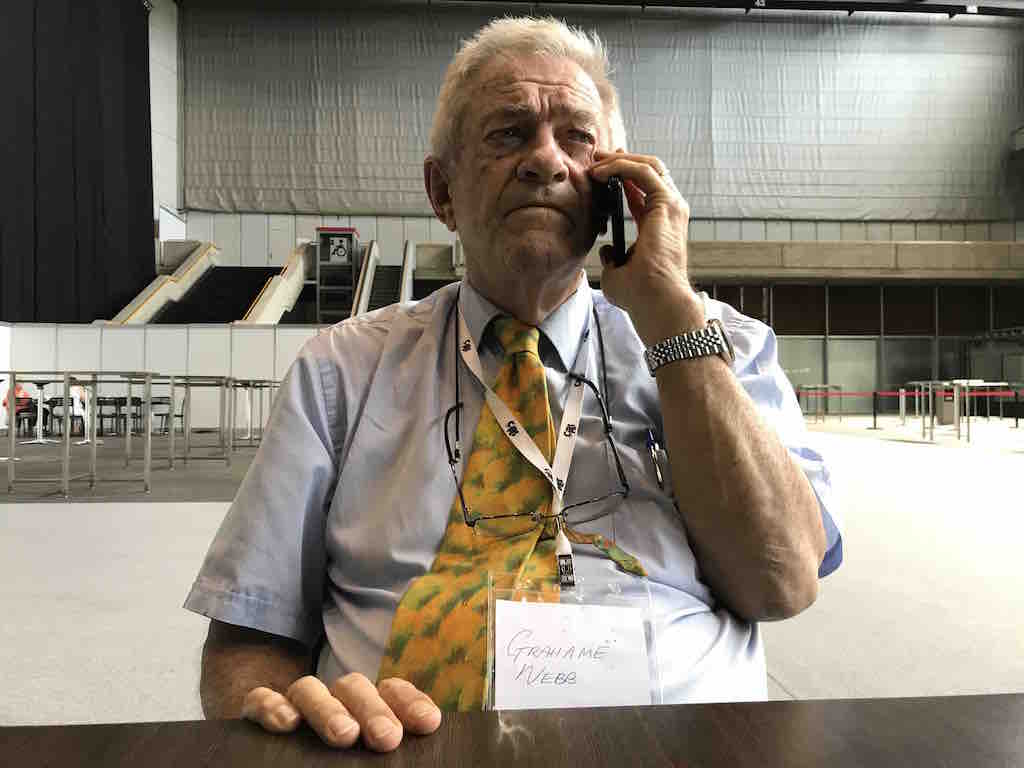

Grahame Webb: Until two years ago, he sold crocodile skins to fashion brands such as Louis Vuitton. Photo: Roberto Jurkschat

Conflicts of interest

Grahame Webb has led the IUCN expert group on crocodiles for decades — he also owns a vast crocodile farm in Australia, where eggs are collected from wild nests. Up until two years ago, Webb said, he sold crocodile skins to brands such as Louis Vuitton. Webb said he had never made a profit from the sale of crocodile skins, and that the sales merely financed conservation efforts.

He said that selling crocodile products was the “best way” to preserve the reptiles and their habitats. He said the skins he sold to Louis Vuitton and Hermès, among others, hold a CITES certificate, while crocodiles are classified as “least concern” on the Red List.

When asked how many of its 15,000 experts reported possible conflicts of interest, the IUCN declined to respond, saying that experts were chosen solely on the basis of their expertise, not the organisations they represent.

Sabine and Thomas Vinke are German herpetologists who moved to Paraguay in 2004. They have written 160 texts in journals and published eight books. They even present a weekly TV programme, Paraguay Salvaje, or Wild Paraguay.

Since moving to Paraguay, the Vinkes have been campaigning for better protection for the red tegu, a lizard that lives in the Gran Chaco forest in Paraguay and Argentina, a fragile ecosystem threatened by the spread of livestock farming. Every year, about 150,000 red tegus are caught for the leather industry, killed, skinned, and shipped to Europe.

The Vinkes believe that the red tegu is endangered, and that trade should be prohibited, or at least severely restricted. But their attempts to protect red tegus have been beset with difficulties.

Under the terms of CITES, the global conservation treaty, the less endangered a species is on paper, the more skins and body parts are available on the market. Therefore, when a species is classified as more endangered, it can cost the fashion industry millions.

In September 2014 the Vinkes submitted a motion to the IUCN to establish a new expert group, with the ultimate goal of working out how the red tegu should be categorised on the Red List. A written agreement to form such a group already existed, so things should have been straightforward. The agreement carries the signature of Simon Stuart, who in 2014 was the head of the IUCN Species Survival Commission.

Sabine and Thomas Vinke: German herpetologists expelled from an IUCN expert group. Photo: supplied

Leather lobby

But Sabine Vinke said that immediately after they submitted the request to establish the expert group their efforts were battled by what she described as the leather lobby in the IUCN — members pushing the idea that trade in reptile skins was the best way to protect certain species.

The Vinkes said Stuart also put roadblocks in their way. He wrote to them in 2014 to say that several IUCN scientists had expressed concern about the creation of an expert group centered on red tegus.

“I would be grateful if you could hold off on appointing any members of the new specialist group or launching any other specialist group activities until we have had a chance to speak,” Stuart wrote in an email.

Sabine Vinke said that in a subsequent phone call, Stuart told them to stop messing with the leather industry. She said he told them to give up the specialist group. “He was very angry and urged us to resign,” she said.

When contacted by this reporter, Stuart said he could not remember the phone call with Sabine Vinke in detail, but denied threatening them. “They are not the sort of things that I would have said.”

Stuart, who worked for the IUCN for 30 years, said the Vinkes voluntarily stopped their attempt to form the group, and that he himself thinks it would be helpful for such a group to be set up. Stuart completed his tenure as chair of the IUCN Species Survival Commission in 2016 after eight years in the role. The 63-year-old is now director of the Synchronicity Earth charity in London.

Years later, in June 2019, the Vinkes published a long-term study in a peer-reviewed journal on the distribution of red tegus, concluding that the lizard population had declined considerably, principally due to deforestation causing habitat loss. Shortly after the study was published, the Vinkes were expelled from the IUCN expert group they were still members of, which specialised in boas and pythons.

In a letter, the group’s chair, Tomás Waller, told the Vinkes that he doubted their data, and that their anti-trade attitude was not in line with the work of the IUCN.

“You have been very clearly working for your own agenda, a radical anti-use, anti-trade one, very far from the objectives and vision of IUCN,” Waller wrote. (In some conservation circles, the phrase “anti-use” refers to an opposition to making money from wild animals.)

“As distasteful as it may seem to some people, there is strong evidence that allowing local communities to sustainably utilise wildlife resources is a proven way to ensure species and habitat conservation — as well as derive important livelihood opportunities to people and ensure the conservation of important indigenous culture,” Waller wrote in an email.

In early December 2018 the luxury brand Chanel declared it would no longer process the skins of exotic animals. Chanel’s president Bruno Pavlovsky said it had become difficult for the company to trace exactly where reptile skins had come from.

Just three days after Chanel’s announcement, an online fashion magazine published an article entitled “Why Chanel’s Exotic Skins Ban Is Wrong”. The authors of the article were all members of the IUCN, including Webb, the head of the IUCN group on crocodiles, and Waller.

Red tegu: Every year about 150,000 are caught for the leather industry, killed, skinned, and shipped to Europe. Photo: supplied

Giraffe trade

Fred Bercovitch is one of the most renowned giraffe experts in the world and a member of the IUCN specialist group on giraffes and okapis. The 67-year-old American is director of the San Antonio-based Save the Giraffes, and has taught as a professor at universities in Japan and South Africa.

When the IUCN/Traffic analysis requested by the six African countries was published anonymously on the CITES website in March 2019, he set out to find out who the authors were, believing their recommendation that the trade in giraffe parts did not represent a threat to the animal’s future was wrong — it did not matter whether it was the most important factor, what mattered was that the giraffe population was shrinking overall.

“I asked half a dozen people from our specialist group, but nobody knew who the authors were. And most of them disagreed scientifically with the IUCN analysis,” he said. “I don’t know anybody who was asked for his opinion before the analysis had been finalised.”

A month before the IUCN/Traffic analysis was published, Bercovitch learned that seven conservation NGOs had sent a letter supporting the African countries’ motion to protect giraffes to the IUCN specialist group on giraffes and okapis. However, the letter had never been passed on to experts like Bercovitch.

This reporter obtained a copy of the letter, which cited scientific data showing that from 2006 to 2015 more than 3,800 giraffe trophies were delivered to the US alone. The letter was addressed to the expert group’s chair, the Australian biologist Fennessy.

In an interview, Fennessy defended the IUCN/Traffic analysis and said he did not know who wrote it. However, an IUCN paper identifies Fennessy as a reviewer of the analysis. An IUCN spokesperson clarified in an email: “At least one member of the core team was in direct contact with each reviewer, or was copied into correspondence with each reviewer.”

At the World Wildlife Conference in Geneva in August 2019, Bercovitch, at the request of the delegation from Chad, made the momentous decision to speak out against the IUCN. It was the first time he had ever done so. In a 10-minute presentation, he made a strong plea for the protection of giraffes. “When I finished my presentation some people from the IUCN were looking at me as if they thought, Who the hell is this guy?”

But, the professor’s appeal worked, and delegates sided with the six African countries, voting 106–21 against the IUCN recommendation. The international trade in giraffe parts would now be controlled for the first time ever.

Momentous decision: At the World Wildlife Conference in Geneva in August 2019, Fred Bercovitch, at the request of the delegation from Chad, spoke out against the IUCN. Photo: supplied

Internal report

Such victories for trophy hunting critics are extremely rare, however.

In 2017 the IUCN Council, the union’s governing body, was faced with a dilemma. The International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW) had applied to join as an IUCN member organisation, but the NGO was explicitly against trophy hunting in all forms. Trophy hunting advocates in the IUCN Council had serious concerns and argued that it would be impossible to build consensus within the IUCN if any member organisation refused to recognise trophy hunting as a valuable conservation tool. The IUCN Council was split, some councillors sided with the IFAW position.

So the IUCN Council commissioned an internal report it hoped would settle the dispute between trophy hunters and their critics, to clarify finally what position IUCN should take.

Responsibility for producing the report eventually fell to the chair of the IUCN’s specialist ethics group, a German lawyer called Klaus Bosselmann.

Bosselmann put together a team of six experts who worked on the report for half a year. By October 2017 it was ready, and its conclusion was truly explosive.

“The crucial question is whether trophy hunting, as practised by individuals and promoted by certain hunting organisations, is compatible with the general objectives of the IUCN. This is clearly not the case,” the report said.

“Any other view would jeopardise the credibility of IUCN for moral and ethical leadership in conservation policy.”

Before the finished report was forwarded to the IUCN Council, however, trophy hunting advocates in the IUCN were given the chance to have their say first.

The chair of the IUCN’s governance and constituency committee, Jennifer Mohamed-Katerere, invited members of the sustainable use and livelihoods specialist group to address the committee on the issue, emails show. The sustainable use and livelihoods group, which Canadian hunter Mahoney is vice-chair of, strongly promotes the “advantages” of what its members call “sustainable trophy hunting”.

Klaus Bosselmann: chair of the IUCN’s specialist ethics group. Photo: supplied

Transparent debate

In a statement to this reporter, Mohamed-Katerere said she had encouraged “full and transparent debate on all issues that come before the committee”.

She said she invited speakers “with different perspectives on the issue and gave them equal time to address the committee. The aim of the expert session was for all the speakers to bring their insights on these issues to the meeting. The objective was to enrich the understanding of the committee members.” (IFAW was ultimately admitted as an IUCN member in November 2017.)

It would not be until September 2019, almost two years later, that the IUCN finally published the complete findings of Bosselmann’s team. But then, after media interest, the report was suddenly removed from the IUCN website. Three days later, it was restored, but with “further information” added — the IUCN had attached page-long statements from supporters of trophy hunting.

In an official statement released around the same time, the IUCN officially disassociated itself from Bosselmann’s report which, the union said, was only an “opinion”, and not the view of the organisation, despite it being issued by its own ethics group.

An IUCN spokesperson told this reporter: “The document is referred to as an opinion because it is in fact an opinion.”

Bosselmann, who teaches in New Zealand and has been the director of the New Zealand Centre for Environmental Law for 20 years, was nevertheless pleased that his team’s report had finally seen the light of day. “I’ve received a veritable flood of emails from several members of the IUCN and many organisations with acknowledgements,” he wrote in an email to this reporter last year after the report was finally published.

In June 2020 the IUCN World Conservation Congress will take place in Marseille, France. The quadrennial congress is the world’s largest conservation event, dwarfing even the World Wildlife Conference. It’s an opportunity for members to vote on new principles to guide the work of IUCN.

After Bosselmann’s report was published, eight IUCN member organisations submitted a motion requesting that the World Conservation Congress recognise its conclusions as IUCN principles.

But last November, the IUCN committee responsible for deciding which topics proposed by member organisations are actually discussed at the congress rejected the motion. That means the next time a resolution on trophy hunting can be debated at the IUCN is 2024.

Mark Jones of the Born Free Foundation, one of the eight organisations that wanted the Bosselmann report recognised, said: “I am personally saddened that the IUCN, an organisation that purports to be the ‘global authority on the status of the natural world and the measures needed to safeguard it’, seems to be so heavily influenced by trophy hunting proponents with vested interests in exploiting wildlife for financial gain.”

This investigation was translated from German and published in BuzzFeed News here. It was supported by the Internews’ Earth Journalism Network Investigating Wildlife Trafficking project