11 Jul The epicentre of Namibia’s rhino poaching

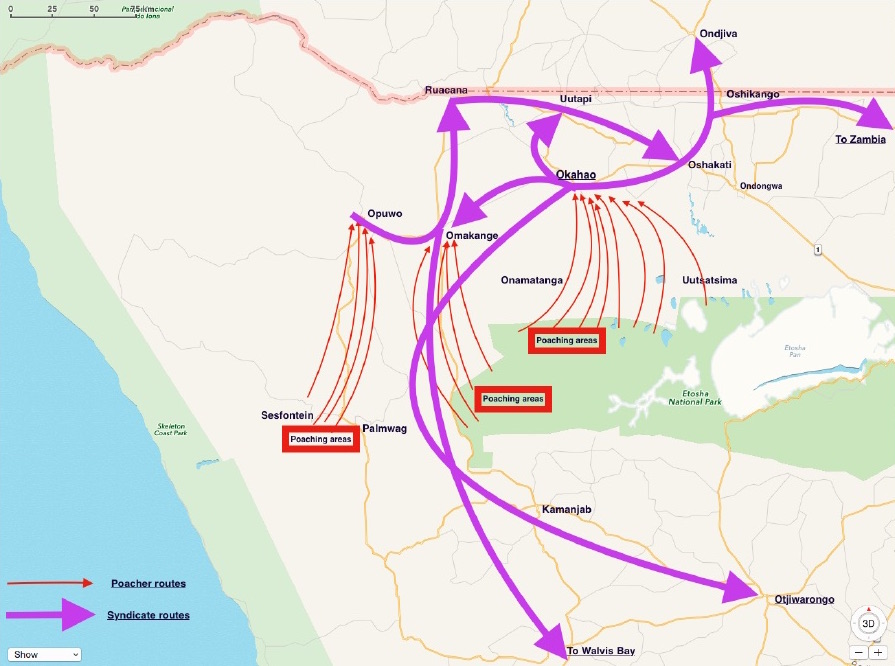

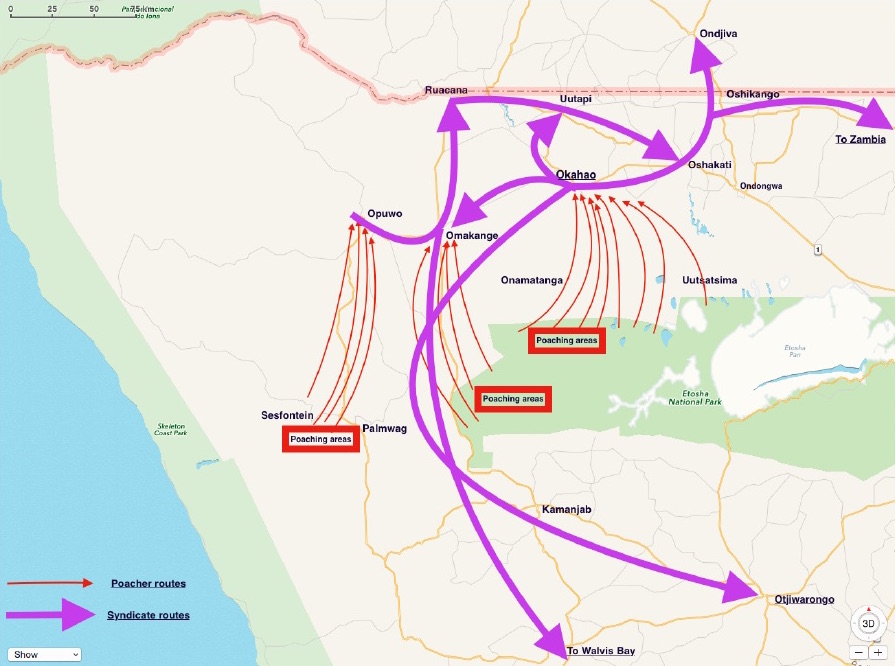

John Grobler visits Okahao, a sleepy settlement near Etosha National Park at the centre of the poaching plague threatening the world’s last viable population of critically endangered black rhinos

Sheetu Amunyela’s sprawling new house on the south-eastern outskirts of town, all built in the past two years. Photo: John Grobler

It is not hard to spot the successful rhino poachers in Okahao: at a time when everyone else in Namibia is suffering from a crippling, four-year-long drought, they are building new houses, buying more cattle and driving fancy new cars.

Their new bars and construction businesses along Okahao’s main road flash new money in garish colours. Some look abandoned halfway – a case of arrested development.

Some occasionally get arrested for rhino poaching, but then mysteriously get out again and carry on like nothing has happened, said my local guide, pointing at one of the new properties in the main road owned by Sheetu Amunyela.

“When the police searched that boy’s place, they found nearly a million dollars in cash hidden in a bag or something. When the police questioned him, he claimed it belonged to his father, but his father said he knew nothing of that money,” the guide said.

Okahao is small, with no more than 2,000 inhabitants, and nothing stays secret for very long. It may have modern tarred roads and two ATMs at the local bank, but it has remained a village.

Sheetu Amunyela, the owner of the new bar – thatched roof and tasteful natural stone, metallic one-way glass windows, still closed – had also built himself another bar (called Uukwamatsi Shebeen) and a sprawling new house on the south-eastern outskirts of town, painted a matching garish pink.

In spite of Amunyela being in jail, work was continuing at his house: a Northern Electricity Distributors (Nored) team was installing a private transformer to link his house to the national electric grid. Such connections cost nothing less than R100,000 – and are payable in cash, in advance.

On July 18, Amunyela and 21 others are to plead formally to charges of hunting a protected species (black rhino). Investigations linked them to six carcasses, but only four horns have been recovered. There is talk of military-grade weapons used.

Most were arrested in June 2015 at the villages of Onamatanga, Uutsatsima and Otjinove, all deeply rural Hai//Om San settlements just outside the northern fence of the Etosha National Park.

Amunyela and three others were re-arrested a few months later after being caught with rhino horns in Windhoek. Most of the poachers are Hai//Om San, but the main players are all from the Oshiwambo-speaking Ogandjera sub-tribe.

As the original inhabitants of the Etosha Pans, the Hai//Om consider their expulsion from the park in 1952 by colonial South Africa’s bureaucrats a historical legal injustice.

“They are, even among the San people, the most marginalised of all,” said Peter Watson of the Legal Assistance Centre in Windhoek. “Unlike other San groups who still have access to their ancestral lands in the Khaudom and western Caprivi, the Ha//Om have nothing.”

A group of eight of the Hai/Om have filed a legal claim with the Namibian High Court for the return of beneficial rights to their ancestral land, he confirmed. Others, under the influence of politically connected clans from Omusati, appeared to have started taking the law into their own hands.

And where the interests of these latter Hai//Om and local rhino-preneurs like Amunyela intersected with larger but as of yet unstated political agendas, rhinos have been dying in large numbers.

Big dreams built on the sand of unrealistic expectations – a case of arrested development on Okahao’s main street

Ground Zero

In her cramped office next to the police station just off the main road in Okahao, the slightly flustered young public prosecutor delved into a dusty filing cabinet to retrieve the court files of two currently pending rhino poaching cases. The magistrate bustled in, requesting the day’s court roll. She apologetically cleared space on her desk, crowded with many other dockets: domestic violence, theft and stock-theft, assault with intent to do grievous bodily harm.

“Sorry, we only work here in Okahao in the mornings. We go back to the Outapi [Regional] Court every afternoon,” an hour’s drive away, she hurriedly explained.

Yes, all of the 22 rhino poaching suspects have been granted bail and yes, she said, nearly all seemed to have paid. And yes, two or three of those were arrested again subsequent to their release for illegal possession of rhino horns, this time in Windhoek.

That most of the suspects were deeply rural and penniless Hai//Om villagers, and that bail was set between R5,000 and R10,000 – and that they seemingly all managed to get all that money together while in jail – seemed not to raise eyebrows.

At the police charge office next door, desk Sergeant Ekandjo showed me the receipt book: a neat, female handwriting acknowledging receipt of R10,000 bail money in cash from Petrus Shipena, believed to be the main poacher of the group. Shipena’s fingerprint is missing from the court docket, I pointed out.

How did he get hold of R10,000 while in a jail cell? Who brought the money? “You will have to ask him that yourself,” laughed the sergeant, not unkindly.

Most of the suspects appeared to have been bailed out while they were being kept in Oshakati’s jail, where they were sent because Okahao’s small holding cells could not accommodate them all, Ekandjo explained. Finding the suspects’ names was difficult: the Okahao bail register, like all other official documentation, is a laboriously large and handwritten in dozens of different hands.

If there is an epicentre to Namibia’s rhino poaching plague that is now threatening the world’s last viable population of critically endangered black rhinos, it is this small police station in Okahao, a sleepy settlement more famous for being the birthplace of Namibian founding president Sam Nujoma.

Situated about 100km north of the Etosha National Park’s north-western boundary, Okahao’s magistrate’s court is dealing with 29 out of 40 rhino poaching suspects charged since 2012 for the Omusati region.

Those 40 suspects are charged in just two cases: the one in which Amunyela and 21 others are to be formally charged on July 18, and a second case involving five suspects, including the national soccer team’s former medic Gerson Kandjii.

Kandjii and his co-accused are due to go on trial on July 27, bureaucracy and lawyers’ timely appearance permitting.

Neighbouring Kunene region’s Opuwo magistrate’s court has the highest number of cases (16), including the only conviction thus far in 2012, court records showed. Overall, the majority of cases have now been postponed for a year or more – as much a result of lack of ballistic results as defence lawyers not turning up at court, said Opuwo chief prosecutor Obert Mosendeke.

Criminal investigations by the police’s over-stretched Protected Resource Unit (PRU), which handles all wildlife, gold and diamond crimes, was not keeping up. Their lack of resources – only three detectives in a staff of 15 – was affecting prosecution: of 200 wildlife crime cases brought before court last year, only five were successful, he said.

The PRU, like the Ministry of Environment and Tourism, did not respond to requests for interviews for the purpose of this investigation.

Situated about 100km north of Etosha’s boundary, Okahao is at the centre of smuggling routes to the north and south

How many black rhinos are left?

Meanwhile, the rhinos are dying. Two weeks ago, the Serious Crime Unit in a sting operation arrested a high-flying young businessman, Amon “Mox” Namwandi, and an associate with four rhino horns, some still fresh. No fresh carcasses have yet been found – and clearly, there has to be one somewhere.

With the Ministry of Environment and Tourism currently auctioning off three black rhino bulls for sports hunting, the actual state of the country’s black rhino population has become a matter of controversy. Official figures are a matter of national secrets: the official rhino database is kept in a vault at the Bank of Namibia, and can only be accessed with the minister’s consent.

The global wildlife trade body CITES estimates the Namibian black rhino population at about 1,800 to 1,900, or about 40% out of a worldwide population of 4,885 animals, including the last free-roaming southwestern black rhinos of southern Kunene. The largest concentration of black rhinos was in the Etosha National Park – was, because the extent of poaching in the park of rhinos, and of all other game, has only recently become apparent.

An aerial block count to verify Etosha figures has repeatedly been postponed due to a lack of funding, though the ministry recently acquired a new helicopter. One helicopter was, however, inadequate for patrolling Etosha’s 22,000 square kilometres; two fixed-wing aircraft previously used appeared to have become unserviceable for lack of maintenance.

The previous Etosha chief warden, Boas Errki, now head of planning and budget implementation at head office, hopes for more funds for maintenance or increased anti-poaching programmes remained slim, well-placed sources warned.

Former Namibian national soccer team medic Gerson Kandjii (third from left) during a match against Botswana in 2010. Photo: Helge Schutz

The first sign of Etosha’s rhino population being secretly hammered by poachers started emerging after the arrest on November 20 2014 of Gerson Kandjii, the Namibian national soccer squad’s former team medic.

Kandjii and four alleged accomplices were charged with the poaching of two black rhinos. It is alleged he entered the national park from a resettlement farm called “Farm Hellas” on the south-western boundary where an accomplice, David Nghidinua, was the local foreman.

The worst poaching, however, has occurred in areas along the north-western boundary fence, where nearly all the second group of 22 suspects came from: mostly Hai//Om people living in the villages of Onamatanga, Uutsatsima and Otjinove.

The Ministry of Environment and Tourism puts poaching losses in Etosha at 100 confirmed cases, but conservation sources believe the figure could be much higher. They estimated that about 150 carcasses have been found over the past 18 months and that many of them were older than 10 years, indicating that poaching had been happening in the national park for a long time, they said.

Earlier this year, the police announced they had discovered 34 carcasses while doing patrols in north-western Etosha, seven of which the ministry later said were fresh poaching cases.

No ballistics, no case

Two months after his arrest in November 2014, Kandjii managed to get bail. In February 2015, he was arrested again, this time for the murder of retired German industrialist Reinhardt Schmidt at his private game reserve some 200km south of Windhoek. Schmidt was expecting the imminent delivery of black rhinos from the Ministry of Environment and Tourism – information that was highly privileged even before being locked away in the bank vault.

Despite Kandjii’s being arrested in connection with a further crime after his release, his four co-accused in the poaching case also subsequently obtained bail. “We did not have any ballistics results yet, so we could not yet prove to the court that they were connected by Kandjii’s gun,” explained Phineas Mpofu, chief prosecutor in the Outapi Regional Court.

Police records showed that all 40 of the cases under investigation in Omusati stemmed from poaching incidents in Etosha, 36 of them arrests made in the middle of last year by Commissioner Kashipulwa Kashihakumwa, the first commander of the Namibian police’s anti-poaching task force.

Kashihakumwa soon thereafter found himself politically side-lined and took early retirement, and was now working for the Shimelane Security company. Of the more than 36 people he finally charged, cases were made only against 22 suspects, with 14 walking free for lack of evidence.

While arrests have dwindled since Kashihakumwa’s retirement, the rhino poaching in Etosha has slowed but not stopped. Increased patrols of the park’s north-western boundary adjoining the Omusati region, an area Minister of Environment and Tourism Pohamba Shifeta confirmed was their main headache, have started yielding results, though.

On May 10, a police team patrolling the Etosha boundary fence picked up human tracks entering the park and leading to a fresh black rhino carcass. Police affidavits detailed how a follow-up operation then led to the arrest of a poacher named Tuakutua Mupia and Eben Levi, an unemployed but well-dressed young man with bullets in his possession he could not explain.

Detective Chief Inspector Hendrik !Karuchab, in a sworn affidavit attached to the case docket obtained in the course of this investigation, explained how they then discovered an older carcass nearby. Interrogation of Mupia and Levi led the police to Festus Muzava, a senior manager based at the local electricity distributor Nored in Ondangwa.

A few days later, on Friday May 18, as he was rushing to the site of a third carcass the police patrol had discovered, he got word that Zambian police had arrested two of their own nationals and a Namibian in possession of rhino horns of Namibian origin, his affidavit noted.

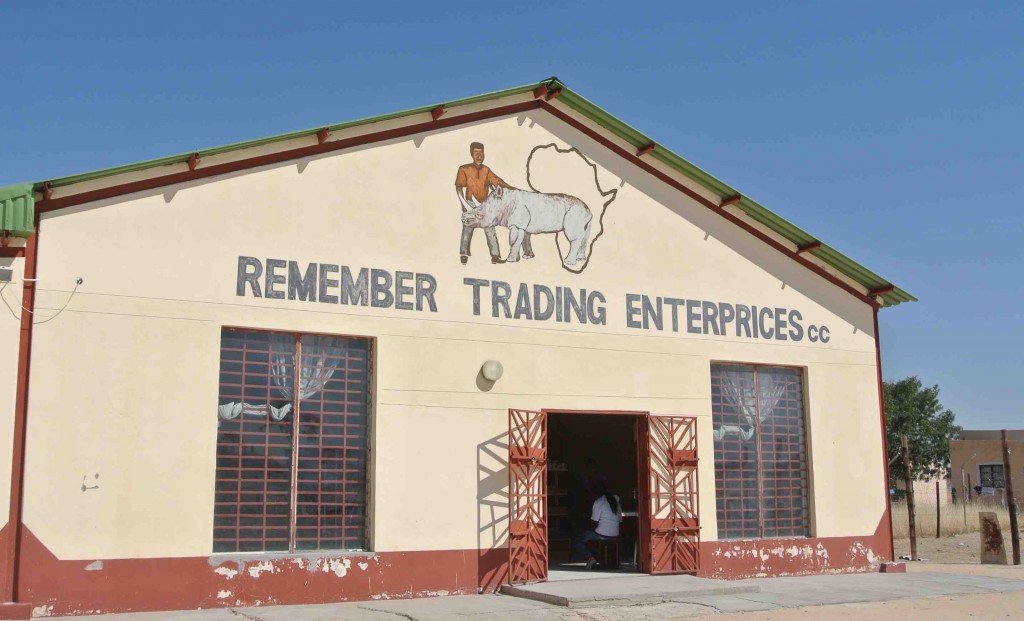

A trading store north of Okahao, on the road to Uutapi

Patterns

As in the Kunene poaching cases, the syndicates were highly selective and had good intelligence on the rhinos’ whereabouts in the Etosha park, said Duncan Gilchrist, a former Etosha game warden and legendary guide of 40 years’ experience from Kamanjab.

As former warden, he had tracked many poachers, some for days on foot, to make an arrest. But this time, “there’s something wrong here. Daar’s ’n slang in die gras [There’s a snake in the grass],” he said.

As in the southern Kunene, the poachers had first gone after the bulls with the biggest horns, and then the cows and calves. It was a pattern: they tracked breeding pairs or cows and calves because that way they made a double score, he said.

But no rural Hai//Om villager was likely to know anyone who would pay him R500,000 for killing a rhino. Any San guy walking into town with a horn to sell was either going to be arrested or robbed very quickly, Gilchrist noted.

“Someone else is sending them in, and that someone else makes the real killing at the end of the day,” he said.

Someone was also buying up horn and moving it out of Namibia, with Angola and Zambia being the preferred routes. The horns confiscated in Zambia by their police around the same time as Mazuva’s arrest at his Nored office were positively identified as of Namibian origin.

Some horn was also being smuggled out via Walvis Bay’s harbour. Local lodge owner Wouter Smith, who lost five black rhinos to the syndicates in 2014, said his information was that police vehicles were used to move the horns to Walvis Bay, where it was smuggled out to Chinese fishing boats via the military section of the port by well-connected, ranking officials.

One such official’s name is Phineas Auene (also spelt Awene), deputy director of the Ministry of Works’ Maritime Directorate in Walvis Bay, who was arrested on July 16 2015 for being in possession of rhino horns. He obtained bail and, according to his social media postings, has since travelled widely internationally.

Word on the streets was that Auene enjoyed the political protection of SWAPO politicians from the Omusati region, with four names – including a current and previous Cabinet minister – most frequently mentioned.

What he has in common with Namwandi, Mazuva and Amunyela, and who they have in common with alleged poachers like Petrus Shipena and Tuakutua Mupia, will depend on who they know among those new businesses along Okahao’s main road, and who will fail to appear in court on July 18. – oxpeckers.org

Find related Oxpeckers investigations in our Namibian poaching links dossier here.