10 Mar Coal-mining web encircles Africa’s oldest game reserve

Ecologically and economically vulnerable areas bordering Hluhluwe-iMfolozi Game Reserve are threatened by ‘get-rich-quick’ coal prospecting rights. Tony Carnie investigates for Our Burning Planet

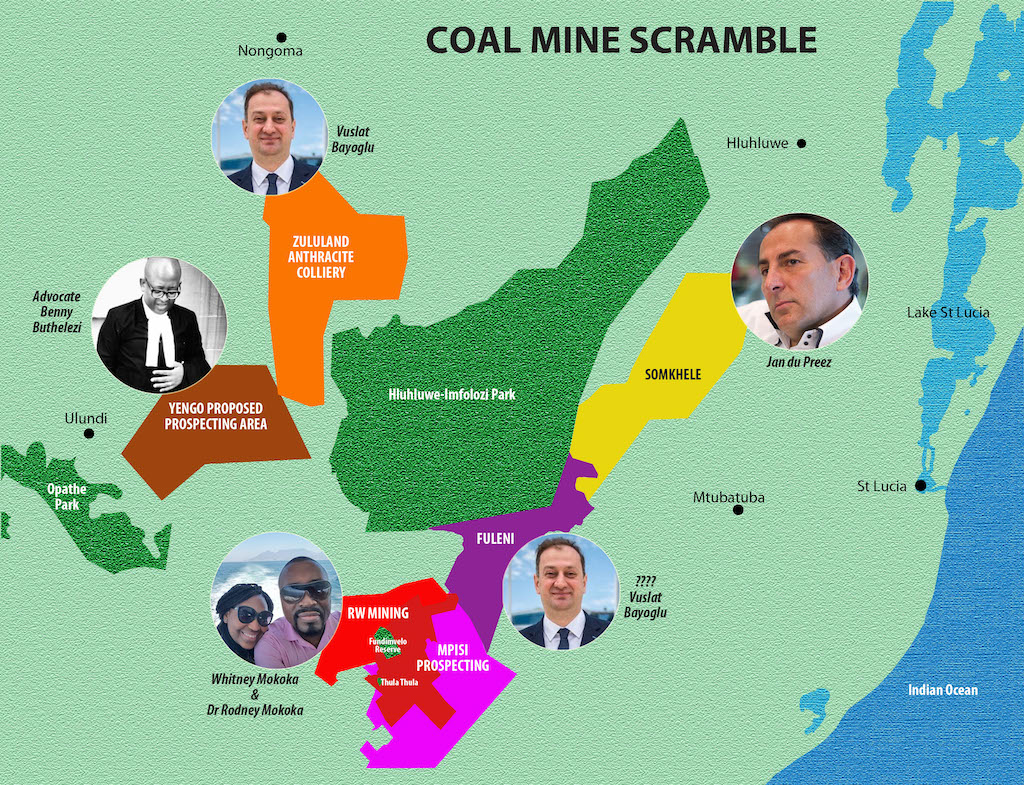

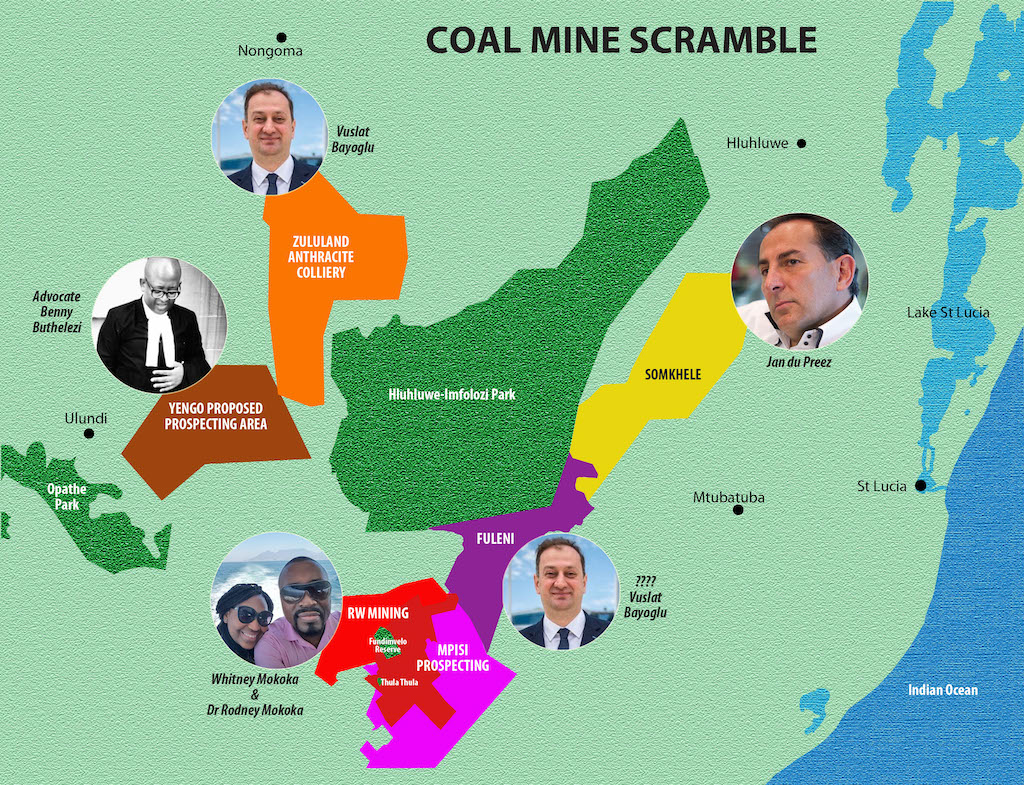

Resource scramble: Increasingly large chunks of rural community land surrounding the Hluhluwe-iMfolozi Park have been targeted for coal mining. Graphic: Sheena Carnie

It has been almost three years since assassins snuffed out the voice of dissent from 63-year-old environmental activist Fikile Ntshangase. She was murdered at her rural home next to the Hluhluwe-iMfolozi Game Reserve in northern KwaZulu-Natal, but the killers are still free.

Now it seems that the powerful opposition galvanised by Ntshangase and fellow anti-coal-mining community members was little more than a pothole. The coal exploration wagon still rumbles forward at speed.

Last year, lawyers acting for Ntshangase’s community won a significant victory when a high court judge found that the government acted illegally in extending coal mining rights to the Tendele Coal Mining company.

Judge Noluntu Bam likened Tendele’s behaviour during the mine extension process to that of an “unbridled horse that showed little or no regard for the law”.

Just short of a year on, Tendele has circulated letters in the Ophondweni, Emalahleni, Machibini and Mahujini areas to notify residents that the company will start fencing off land and building new coal-hauling access roads “from 06.00” on March 15.

It remains unclear how many more residents will have to leave their homes, farmland and communities to make way for Tendele’s expanded coal mining operations.

But these residents are not alone in fearing for their future. It is a region where hundreds of people have been turfed out over recent decades.

Existing coal mines and new prospecting blocks now virtually encircle the Hluhluwe-iMfolozi park, which was established in 1876 and incorporates one of the continent’s first “wilderness” zones.

One of the many homesteads on the fence line of Tendele open cast coal mine near Mtubutuba. Photo: Rob Symons

The Menar group

Adjoining the northwest section of the park, the Zululand Anthracite Colliery (ZAC) also has plans to build a new shaft next to the Masokaneni community.

The ZAC mine, first developed in 1987 by the BHP Billiton group, has changed hands a number of times and is now owned by the Menar group, led by Turkish-born mechanical engineer Vuslat Bayoğlu.

More recently, a company known as Imvukuzane Resources was granted environmental authorisation to sink 55 coal prospecting boreholes in the Fuleni area, which directly abuts the southern edge of the Hluhluwe-iMfolozi wilderness zone.

Full details of the Imvukuzane prospecting company were not advertised, but the government authorisation notice was sent to Gerhard Cronje, head of projects for Bayoğlu’s Menar/Canyon Coal group.

A search of the Companies and Intellectual Property Commission (CIPC) database found that Imvukuzane Resources has three directors: Bayoğlu, Ali Ihsan Naldoken and (former judge) Jerome Ngwenya, who chairs the Ingonyama Trust.

Previous attempts to mine the Fuleni area by the Ibutho Coal group met with strong resistance when it emerged that several hundred homes had been earmarked for destruction or relocation.

Rodney and Whitney Mokoka. Photo from Rodney’s Facebook page 2016

RW Mokoka 7 Mining

Just south of Fuleni, another new entrant is eyeing the land in the Ntambanana area, including the entire Thula Thula private game reserve, for coal prospecting rights. This group, with no prior experience in coal mining, is RW Mokoka 7 Mining.

CIPC records show it has just two directors: Dr Rodney Mokoka and his wife, Whitney. Mokoka is a Pretoria-based physician who has served as team doctor for the Banyana Banyana national soccer team for several years. The couple also established the Mokoka Foundation, which sponsors soccer tournaments for youngsters in poor or rural areas.

One of his environmental consultants let slip that Mokoka has “about 20” other coal prospecting applications pending across the country — a statement confirmed by Mokoka himself when Our Burning Planet spoke to him.

Mokoka said his interest in coal mining was sparked while working as a doctor in Emalahleni (Witbank) for seven years, where he “got to know some guys who are very competent (in the coal industry)”, including geologists and metallurgists.

“As a doctor, you can bring huge change to patients’ lives, but in mining you can bring huge change at a broader community level and also create jobs and training… If there is someone who generates revenue, it’s not all about you. You are giving others hope on a bigger scale.”

When asked about the often negative social and environmental impacts of coal mining, Mokoka said: “Yes, we need green energy, but the transition will take 10 to 15 years. So, in short, there are hunger and health issues (now). So we have to plan and have a balance while limiting carbon emissions.”

Conceding that he had no experience in the coal mining business, Mokoka gave no indication of how he planned to raise capital or skills to establish a mining operation. He also dodged a direct question on whether he was acting on behalf of bigger players.

Advocate Benedict Buthelezi (left) with former president Jacob Zuma during a court appearance in 2021. Photo: Sandile Ndlovu / Daily Maverick

Yengo Resources

Similar question marks swirl around another nearby coal prospecting venture by a company registered in 2017 as Yengo Resources. CIPC records show that the sole director is Benedict Nqabayethu Buthelezi, a Johannesburg advocate who has provided legal services to former president Jacob Zuma, former South African Airways board chair Dudu Myeni and businessman Peter-Paul Ngwenya.

Contacted for comment and clarity on his recent Yengo mining venture, Buthelezi suggested that practising law and an interest in mining were not “mutually exclusive”.

Buthelezi said he grew up in the Ulundi area in KwaZulu-Natal and was approached by local community members to lodge a coal prospecting application on their behalf.

“We are working with the local chief and induna to do this application… I’m not a miner, but the Ulundi area is highly impoverished and there are no job opportunities,” he said.

Buthelezi did not elaborate on who would provide capital and skills if his application was successful, but Our Burning Planet has seen official correspondence that Yengo has an “in-principle partnership agreement” with a relatively obscure company called Northfield Coal.

CIPC records suggest that Northfield was registered in 2017 and is based in Utrecht. The listed directors are Quinten Claud Swart, Francis John Joslin, Malcolm Keith Johnson and Johannes Alfred Gerber.

Mountains of coal await export from the Richards Bay Coal Terminal in KwaZulu-Natal. Photo: RBCT / Andre Meyer Photography

Recent scramble

The recent scramble for new prospecting and mining licences around Hluhluwe-iMfolozi comes at a time when demand for thermal coal and coking coal is rising sharply, despite urgent calls by climate-change scientists to shift sharply from fossil fuels to renewable energy.

The price of coal reached an all-time high of $457.80/tonne in September 2022, before plummeting over recent months.

According to the International Energy’s Coal 2022 analysis: “Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has sharply altered the dynamics of coal trade, price levels, and supply and demand patterns in 2022… This has prompted a wave of fuel switching away from gas, pushing up demand for more price-competitive options, including coal in some regions.

“Russia is the third largest coal exporter in the world and the sanctions have as a result given rise to a reshuffling of global trade flows as buyers, especially in Europe, seek alternative supplies… The gap left by Russian coal supplies in Europe has been largely filled by South Africa, Colombia and other smaller producers such as Tanzania and Botswana.”

Late last year, former New Zealand prime minister Helen Clark warned that growing demand for coal was likely to push mining companies into more environmentally and socially sensitive areas across the globe.

“Pressure to approve new mines quickly could mean not enough time is allocated for consultation and impact assessment. In many countries, we are already seeing a move towards streamlined or fast-tracked approval processes, and while the motivations for that may be legitimate there is a risk of harm to communities and environment if there are not enough safeguards,” she said.

Women from the Mfolozi Community Environmental Justice Organisation demonstrate outside the Pietermaritzburg High Court. Photo: Supplied

‘Job destroyers’

Bayoğlu of Menar and Tendele’s chief Jan du Preez have both been scathing in their criticism of community members and activists who have pushed back against the mining onslaught around Hluhluwe-iMfolozi, characterising them as “job destroyers”.

But Jeremy Ridl, an environmental attorney representing the Umfolozi Big Five Trust, suggests that in its present structure, the South African coal mining industry only benefits the economic elite. The trust administers several community areas proclaimed as nature reserves and incorporated into Hluhluwe-iMfolozi Park, with two lodges currently in operation.

In a recent submission to the Department of Minerals Resources and Energy, Ridl suggested that the department’s basic assessment process was nothing less than a “licence to destroy. It is being used to justify avoidable destruction. It envisages trashing the homeland of a community and offers them nothing in return.”

Nor did the basic assessment process for the Yengo coal prospecting application consider the wider issue of land rights for marginalised and vulnerable communities, he said.

“The land identified is another example of miners choosing soft targets, where disempowered communities have no resources to defend their rights, their heritage, their culture or their wellbeing. Is this ethical? Is this consistent with the spirit of ubuntu?” he asked.

Who would profit from the mine? How much profit would remain in the local area after people gave up their land for mining, Ridl asked.

“As history suggests, applications for prospecting and mining rights are horribly one-sided and communities such as my clients are powerless to have an equal say in the decision of the competent authorities, who traditionally, strongly favour mining, as indeed it is their mandate to promote mining.”

“The current application, being for prospecting rights, is obviously relatively non-invasive, and the impacts are obviously minimal when compared to mining. This will be used as the justification for the grant of the prospecting rights.

“This is not the point. Armed with prospecting rights, and if the target mineral is found to exist in viable quantities, the probabilities are that a mining right will be issued.”

It was, therefore, necessary at an early stage, while considering the merits of an application for a prospecting right, that the merits of an application for a mining right should also be considered.

“It is a pointless exercise to consider the impacts of prospecting alone, when the true impacts will only be felt during mining. It is equally pointless to issue a prospecting right if ultimately mining is unacceptable in the proposed area.”

‘Under siege’: Cavernous coal mining pits in the Somkhele area, surrounded by rural homesteads. Photo: Rob Symons

The mining cause

Ridl also noted that Minerals Minister Gwede Mantashe had publicly pinned his colours to the cause of mining.

“This inspires no confidence that his decision will be fair to affected communities… These comments are accordingly submitted with the expectation that they will be ignored, and that this matter will ultimately be resolved on appeal to the minister of forestry, fisheries and the environment, or more likely, on judicial review by the high court.”

Similar concerns have been raised by Durban attorney Kirsten Youens, who represents communities in the Mpukonyoni and Somkhele area.

“It is our experience that the decisions made by government are too often blinkered by the promise of employment and other socio-economic benefits without weighing these benefits up,” she said.

Her colleague, attorney Janice Tooley, said: “One thing is for sure, the whole region is under siege.

“We need to start looking at cumulative impacts on water, climate change, sustainable livelihoods and community cohesion and cultural heritage, food security, biodiversity, and ecotourism… I can’t see how any of these mines can be viewed as sustainable development, but rather short-term gain for a relatively few — and widespread, intergenerational destruction for the majority.”

This investigation was first published by Our Burning Planet here