10 Feb Uncharted waters: Inside the political battle for control of the Orange Basin oil and gas resource

As Namibia looks set to enter the deep and uncertain waters of the international oil industry, John Grobler analyses the legal and technical challenges emerging as the biggest obstacles

Contrasting context: Flamingos forage along Namibia’s fragile coastline as an offshore oil rig looms on the horizon — a stark image of the high-stakes struggle between ecological preservation and the political, legal and technical battles shaping the future of the Orange Basin’s oil and gas boom. Photo: John Grobler

With youth unemployment now exceeding 50% in Namibia and rising poverty undermining long-term development objectives of Namibia’s Vision2030, there is huge pressure on the government to facilitate the establishing of an off-shore oil industry. Photo: John Grobler

A lack of technical expertise and a legal vacuum in the form of a complete lack of gas-related legislation caused by elite capture of the state petroleum company Namcor and the Directorate of Energy at the Ministry of Mines and Energy for the past decade are raising fundamental questions over Namibia’s not-too-distant future as a major African oil producer.

Over the past 12 months, off-shore exploration has not only confirmed a proven resource of 21-billion barrels of light sweet crude, but also widespread deposits of high-grade wet condensate gas that could be a complete game-changer for the long-stalled Kudu Gas Field project as the central feature of Namibia’s industrialisation policies.

But even though Kudu is central to Namibia’s Vision2030 and liquid natural gas (LNG) has been a prominent feature of the country’s efforts to meet rising electricity demands since 2015, there exists a legal gap that has not been addressed for 30 years.

When the Petroleum (Exploration & Production) Act 1 of 1991 and its 1992 amendment were promulgated, they repealed but not replaced all pre-independence laws and regulations governing the commercial trade in liquid petroleum gas and all related derivatives. The expectation was that this would be addressed in a separate law specific to the Kudu gas field in due course.

This legal vacuum has become even more obvious since the introduction of LNG technology, developed by the oil industry as its solution to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions restrictions imposed by the 2015 Paris climate change agreement.

It is not just the Petroleum Act amendment that is missing in legal action: the tabling of the Namibia Energy Regulator Bill and new Gas Bill has been repeatedly delayed since 2018 in the political tussle for control of the future of the country’s nascent oil industry.

Power(ful) mess: Delegates pose on stage at the 2025 Namibia Oil and Gas Conference, a polished public display that belies a deepening political power struggle over control of the country’s oil sector, marked by delayed petroleum law reforms, factional battles within government and Namcor, and corruption cases that have thrown Namibia’s energy future into sharp uncertainty. Photo: John Grobler

Power struggle

This power struggle was about to come to a head in Parliament after the Speaker (and former prime minister) Saara Kuugongelwa-Amadhila last year postponed an urgently required amendment to the Petroleum Act to February 2026, in what was widely seen as an effort to frustrate President Netumbo Nandi-Ndaithwah’s efforts to gain full control over an increasingly corruption-prone industry.

Broadly speaking, the power struggle was between the resource-nationalist camp and a more business-minded faction with vested interests in the local shareholding of Petroleum Exploration Licences (PELs) that emerged in the speculative deals of the oil exploration era of 2012-2015.

Those battle lines were largely drawn by the former, now late President Hage Geingob when he appointed the former (2005-2015) MD of state petroleum company Namcor, Obeth Kandjoze, as minister of mines and energy, and moved the former (2005-2015) petroleum commissioner Immanuel Mulunga into Kandjoze’s former position while rising Namcor star Maggy Shino was appointed as petroleum commissioner.

But after Geingob’s death in February 2024 of cancer, Namcor management descended into shambles as open war broke out between Mulunga and the Namcor chair Jennifer Comalie, whom he allegedly tried to have framed for possession of drugs for trying to get him fired. The case was struck off the court roll in 2023.

In August 2024, Mulunga and his chief financial officer were suspended over unauthorised transactions in Angola, and in July 2025 Mulunga was arrested with six other suspects, including two other senior Namcor managers and four businessmen, in connection with a fraudulent R500-million military fuel supply contract. They were all denied bail and remain in custody, pending a trial date later this year.

Power concentrated: A SWAPO campaign billboard linking offshore oil platforms to promises of national prosperity captures how President Netumbo Nandi-Ndaitwah’s early consolidation of control over Namibia’s upstream oil sector has redrawn political battle lines – concentrating power in the presidency, fuelling opposition claims of reduced accountability, and intensifying factional contestation ahead of the 2027 SWAPO Congress amid high-profile corruption arrests. Photo: John Grobler

Battle lines

When in March 2025 incoming President Netumbo Nandi-Ndaitwah, the Directorate of Energy and Namcor assumed direct control of Namibia’s future upstream oil industry, no one including senior ministerial officials were very surprised that the battle lines were being drawn.

“What we are seeing now emerging in the Parliament is a contest of political positions with an eye on the run-up to the 2027 SWAPO Congress,” said Graham Hopwood, executive director of the Institute of Public Policy Research.

Upon her appointment on March 21 last year, Namibia’s first female president in her re-organising of her new slimmed-down Cabinet, nominated noted resource nationalist Natangwe Ithete as her deputy prime minister and minister of the now-renamed Ministry of Industrialisation, Mines and Energy.

She also stripped the former Ministry of Mines and Energy (MME) and Namcor of all upstream functions, moving those into a new Upstream Petroleum Unit in the Office of the President.

This was widely criticised by the political opposition as a regressive concentration of power that undermined political transparency and accountability, but seemed justified when in July the Anti-Corruption Commission arrested former Namcor MD Imms Mulunga, two senior managers and the owners of three fuel distribution companies for the alleged corrupt mismanagement of a military fuel supply contract.

An oil tanker lies at berth in Walvis Bay, a visible symbol of Namibia’s accelerating oil ambitions even as presidential control, a de facto moratorium on exploration rights, opaque share deals by global majors, and shrinking public access to licence information expose growing tensions over transparency, legality and public accountability in the Orange Basin boom. Photo: John Grobler

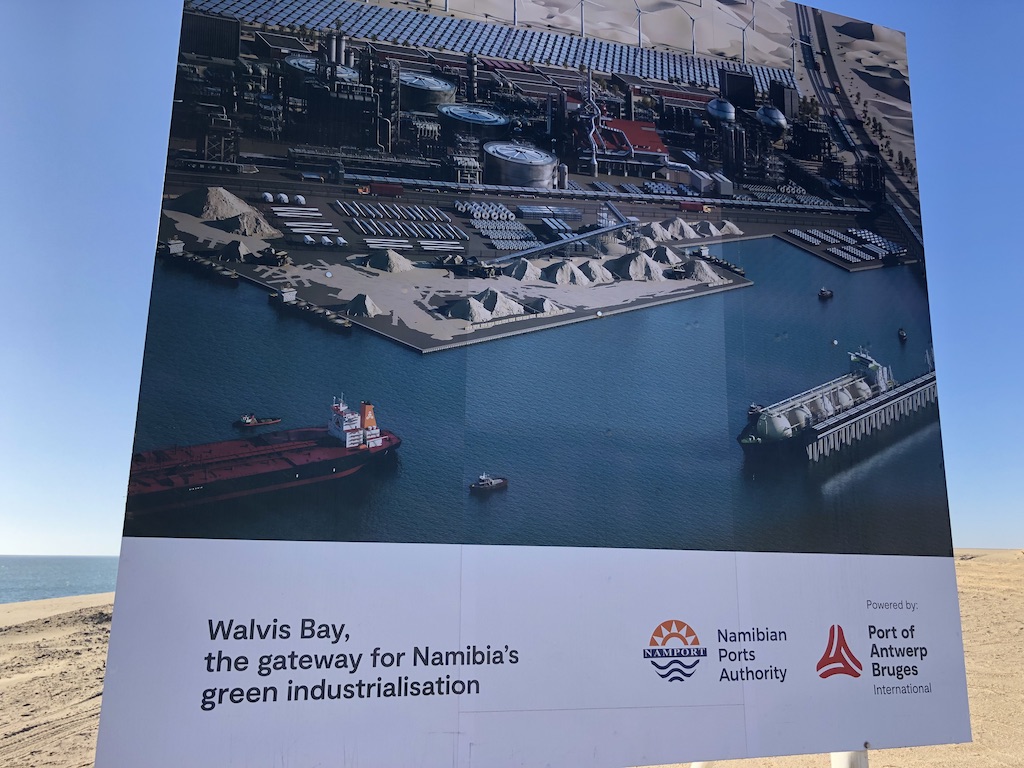

Scramble: NAMPORT’s vision for Walvis Bay as a hub of ‘green industrialisation’ is unfolding at the same time as a largely unseen scramble for Orange Basin oil rights, where a presidential freeze on exploration licences, quiet buy-ins by international majors and the removal of key records from public scrutiny have reshaped who controls Namibia’s offshore future. Photo: John Grobler

Exploration rights

The president also issued an informal moratorium on the issuance or alteration of ownership of oil exploration rights (PELs). When Ithete defied her by extending a lapsed PEL on behalf of a company whose owners were closely associated with her predecessor, the late President Hage Geingob, she immediately fired Ithete from both his Cabinet positions.

Despite the moratorium, international oil companies have been snapping up any available shares in the Orange Basin licences, according to the latest available Namcor data of August 2025.

Over the past few months, the Orange Oil Basin discoveries of 21-billion barrels of oil triggered a scramble for oil exploration rights in the Walvis Bay and Namibe Basin, with exploration set to expand further north up the coast, where ExxonMobil now holds four blocks adjacent to the Angolan maritime border.

Super-majors like Chevron and Qatar Energy, the world’s largest exporter of LNG, now hold shares in at least five prime offshore Namibian oil blocks, but this is not visible from the publicly available data.

As in South Africa in the wake of the ongoing reforms and reorganisation of the Central Energy Fund (CEF) and PetroSA, there was a marked clampdown on publicly available information on oil exploration rights holders last year.

“I’m sorry, but [statutory] inspections of licences are no longer possible because all those files have been moved to the Office of the President,” said a senior staff member of the Directorate of Energy, which is now restricted to dealing only with the downstream retail sector of fuel distribution.

A pattern of statutory elision and lack of public consultation has now become visible on both the Namibian and South African sides of the Orange Basin. Last year, the South African environmental lobby won a major legal victory when the Western Cape High Court ruled that TotalEnergies and Shell had not adequately consulted with local communities in obtaining environmental clearance certificates for oil exploration off the West Coast.

Outdated acts: An ultra-deepwater drilling rig operating off Namibia’s coast reflects how weak regulation and limited in-house technical expertise have tilted the Orange Basin in favour of foreign oil majors, allowing lucrative stakes in a 21-billion-barrel discovery to be secured under an outdated Petroleum Act that critics warn is enabling elite capture before production even begins. Photo: John Grobler

Empty promises: The introduction of LNG is part of a regional plan to use gas to expand mining of lithium, copper and rare earth minerals in the Namib Desert and Namaqualand bordering on the Orange Basin. But in the Brandberg area, lithium mining by Xinfang Lithium Corporation of China has started displacing people like the Matsuib family from their crystal-mining claims and brought a new threat to the critically endangered black rhinos in the area. Photo: John Grobler

Technical know-how

The investor-friendly nature of the outdated Namibian Petroleum Act that, unlike South African legislation, does not include any references to the emerging LNG sector, and a lack of official technical know-how have made Namibia a much more attractive option for foreign investors looking to get a foot in the door of a future Orange Basin oil bonanza.

A Namibian oil bonanza boom is no longer a question of if, but when, as discoveries exceed even the wildest expectations. Over the past year, drilling by the Deepsea Mira ultra-deep exploration rig on just three blocks licensed to Galp Energia, Azule Energy and BW Kudu has confirmed a total proven resource of 21-billion barrels of light crude and a broad swathe of high-grade wet condensate gas at the northern end of the off-shore Orange Basin.

Just a 5% share in any good oil block could translate into a US$250-million profit within the first five years of production, Texas-based Stemper Oil chief executive Grayson Anderson told a Houston-based news outlet in November in sharing the news of their acquiring 32.9% in Vena Gemstones and Mining’s PEL 107, and 5% to 20% in three other licences in the Orange and Walvis Bay off-shore basins.

“The terms imposed by the old Petroleum Act are hugely advantageous to the oil companies with existing rights, which is why I think we’re seeing this delay of the Petroleum Amendment Act since last year,” said Corinna van Wyk of the Legal Assistance Centre (LAC) in Windhoek. “It suggests a worrisome trend of elite capture of the oil and gas sector even before it has started,” she warned.

Reviving stranded assets: Newly appointed Minister of Industrialisation, Mines and Energy Modestus Amutse (4th left) and BW Kudu country chair, Klaus Endresen (3rd right) on a site visit to the former De Beers mining operations in the Tsau//Khaeb Park. Photo: MIME

Legislative gap

The single-biggest legislative gap is the complete lack of a legal framework for the exploitation of natural gas and LNG, an anomalous omission given that the Kudu gas field, first discovered in 1974, is central to Namibia’s electricity and the green hydrogen development strategies.

This strategic omission of LNG had become increasingly evident since 2014-2015, when Nampower awarded a contract for a 250MW, turnkey gas-to-power solution to Xaris Energy – an SA-Namibian joint venture closely associated with former interim president Nangolo Mbumba – and Namcor commissioned the construction of a R7-billion LNG port and terminal in Walvis Bay.

Although the Xaris contract was set aside by Namibia’s Supreme Court in 2018 for tender irregularities, the Namibian Electricity Control Board in January 2022 re-awarded this same contract – now increased to 800MW – to the same company that had since reconstituted itself as a Dubai-registered entity.

At the same time, the Electricity Control Board also handed little-known BW Energy, who in 2017 took up a 56% share in the Kudu gas field after Gazprom’s 2016 exit, the rights to build and operate the Kudu Power Plant for 400-800MW of electricity supplies.

BW Energy (Namibia) then in 2021 upped its Kudu share to 95%, acquired a 30% share in the controversial, Canadian-owned Okavango Basin oil and gas explorer ReconAfrica and renamed itself BW Kudu.

Waiting in the wings: An oil drilling rig being refitted and refurbished in anticipation of a coming boom in the Namibian off-shore oil and gas exploration industry where a lack of depth in the local skills pool has been identified as a priority area for Namibia’s industrialisation policy. Photo: John Grobler

Kudu gas field

BW’s gradual acquisition of the Kudu gas field raised many eyebrows. As a dry gas deposit of nearly pure methane, the industry view had always been that it could only be exploited as fuel for a gas-to-power plant, as envisaged under Vision2030.

Because the price of electricity is heavily regulated, that limited any future profit and rendered the estimated R20-billion price tag for a 170-km-long sub-sea pipeline to bring the gas to an onshore power plant uneconomical.

But with the discovery last year of a belt of high-grade wet condensate gas along the southern and western perimeters of the Kudu licence, that looks set to change. As a super-saturated form of the greenhouse gas methane, it is highly prized in the oil refining industry as a source of everything from propane, butane, isobutane, petrol and plastics, among others.

Selling those products would greatly de-risk the otherwise prohibitive cost of a subsea pipeline – if there was a legal framework in place and sufficient financial incentives to do so.

In February 2025 BW Kudu country chairperson Klaus Endresen, in closing remarks at a public stakeholders meeting in Walvis Bay to announce plans to drill five appraisal wells starting with Kharas-1X, noted that results from Galp’s drilling programme of the Mopane prospect in Block 2813A immediately west of Kudu “.. could also be of some importance” to the future development of the Kudu licence.

Seals lounge on an oil tanker in Walvis Bay, hinting at what was once a closely held secret – that the neighbouring Mopane prospect dwarfed earlier discoveries – while behind-the-scenes influence, disputed gas pricing and unresolved legal gaps have quietly shaped the stalled fate of the Kudu project and Namibia’s delayed entry into the gas and LNG era. Photo: John Grobler

Guarded secret

Endresen declined to expand on that cryptic remark at that meeting or in subsequent emailed exchanges, but may have known what was then still a highly guarded secret: the Deepsea Mira had a month earlier confirmed the Mopane prospect to be a massive 10-billion barrel deposit of sweet light crude, eclipsing TotalEenergies’ trail-blazing discovery in February 2022 of the 6-billion barrel Venus field as Namibia’s largest oil-field.

“The Kudu guys had basically captured the then-MME from 2015 or so onwards, and they had even set the price of gas at the time in USD/GJ [US$ per giga-joule, the American standard],” explained Dr Detlof von Öertzen, a nuclear energy specialist and past director of Nampower.

If the relatively unknown BW Energy had the full institutional political backing they were enjoying at present when they took over from Gazprom as Namcor’s partner of the Kudu gas field in 2017, it was likely the project would have gone ahead eight years ago despite the legislative gaps, he said.

But concerns over an alarming increase in irregularities at Namcor and a high set price for gas that would have to be passed on to consumers in the form of higher electricity tariffs led to the Nampower board pulling the plug, he wrote in a response to a question about why Namibia had for the past 10 years not addressed the legal vacuum in respect of natural gas and LNG.

“[Given] what we know about the Orange Basin now and did not know back then, it’s good that Kudu did not go ahead then as the [already agreed-on] gas price would not have been viewed favourably, given that the amount of gas is much larger than what we realised in the mid-2015s,” he stated.

Despite these headwinds, key MME officials like petroleum commissioner Maggy Shino continued to push the Kudu gas-to-power project. “I suspect but have no proof that there is a huge upside for [Kudu] if they can ensure that natural gas landings have a special dispensation,” Von Öertzen opined.

Focus point: Namcor’s Walvis Bay Gasport, earmarked as a future special economic zone alongside a new LNG terminal, has become a focal point for Namibia’s wet gas condensate ambitions – with refinery plans advancing on paper even as zoning rules, SEZ legislation and key energy bills remain locked away in the Office of the President. Photo: John Grobler

Earmarked: The coastal township of Lüderitz is one of several ports earmarked for future special economic zones linked to Namibia’s wet gas condensate ambitions, even as refinery plans move ahead amid unresolved zoning rules and delayed energy legislation still held within the Office of the President. Photo: John Grobler

Wet gas condensate

Will that upside be in the wet gas condensate and the special dispensation of the future special economic zones being planned for the ports at Walvis Bay, Lüderitz and Boegoebay, in conjunction with the Port of Rotterdam?

Over the past year, environmental notices have been issued for three refinery projects to be located respectively in Walvis Bay’s Gasport area, the Farm 58 Industrial Park 10km outside of Walvis Bay and one in Swakopmund’s industrial area.

According to the Walvis Bay municipality’s Town Planning Department, hazardous industries such as an oil refinery under current bylaws have to be located at Farm 58, but the Walvis Gasport area of 500ha adjacent to the new LNG terminal was identified as the future special economic zone two years ago already.

“We’re still waiting for the legal guidelines from the town council for any rezoning of this area,” said the official on condition of anonymity as she was not authorised to speak to the media.

Those guidelines are expected to be determined by the future legislation for the special economic zones – but like the Gas Bill and National Energy Regulatory Authority (NERA) Bill, those are now in the hands of the Upstream Petroleum Unit in the Office of the President and remain out of sight behind firmly shut bureaucratic doors for the moment.

John Grobler is a Namibia-based associate at Oxpeckers Investigative Environmental Journalism. This is the fourth in a series of #PowerTracker transnational investigations that interrogate the environmental, socio-economic and political impacts that the Orange Basin Corridor oil and gas developments could potentially bring.