20 Nov Power, land and secrecy

After nine months of chasing information about renewable energy land lease deals across South Africa, we sat down to reflect on what we learned. Roxanne Joseph reports

Ambitious ask: As journalists, PAIA is one of the most important tools we have for getting hold of difficult-to-access information. In this instance, we had mixed results with regards to what we could and could not get access to do. Photo: Ihsaan Haffejee

In 2025, the Oxpeckers #PowerTracker team set out to test one of South Africa’s most important transparency tools, the Promotion of Access to Information Act (PAIA), to open up the black box of renewable energy land leases.

We submitted a series of requests to key stakeholders in the sector, including Eskom, independent power producers Red Rocket Energy, Mainstream Renewable Power, Hydrogène de France (HDF Energy), the SOLA Group (SOLA) and Nepsa Energy (Nepsa), as well as the Steve Tshwete local municipality.

Our goal was simple but ambitious: to access information about land lease agreements between landowners and independent power producers (IPPs). We wanted to know the terms, beneficiaries and financial arrangements behind these deals – and, if possible, to see copies of the lease agreements themselves.

At the heart of these requests was a public-interest question: who controls the land driving South Africa’s energy transition, and who benefits from it?

Staying silent: Eskom only engaged after publication – and even then, its land lease agreements stayed hidden. Photo: Mark Olade

Mixed outcomes

The responses revealed a mix of progress and persistent opacity. Eskom, SOLA and Nepsa provided limited information about existing land leases but were unable to share copies of the agreements themselves, citing confidentiality.

Red Rocket Energy and Mainstream Renewable Power refused to answer any of our questions, stating that they too had to abide by confidentiality clauses.

The Steve Tshwete municipality, which leases land for the Hendrina Wind Energy Facility, acknowledged our request but failed to provide any substantive documentation.

Several other entities ignored the requests entirely, offering no formal outcome. We followed up with direct emails, phone calls and WhatsApp messages, but responsiveness varied widely. The process stretched over months, with small wins accompanied by long silences.

Eskom only responded to questions the day after we published an investigation in October, Inside renewable energy land deals. The public utility’s media desk said its land lease programme was designed to fast-track new generation capacity by making Eskom-owned land available for renewable projects.

Proof of its effectiveness, Eskom said, was Red Rocket Energy achieving financial close on the Tournee Solar Park – “the first project to advance to construction under our pioneering land lease programme. This milestone demonstrates the critical role of public–private partnerships in unlocking South Africa’s renewable energy potential.”

Asked about lease agreements that did not go ahead, Eskom’s media desk said the land parcels awarded “will be used for future renewable energy initiatives or new partnerships, in accordance with changing market conditions and best practices”. It did not share copies of land lease agreements requested, citing confidentiality.

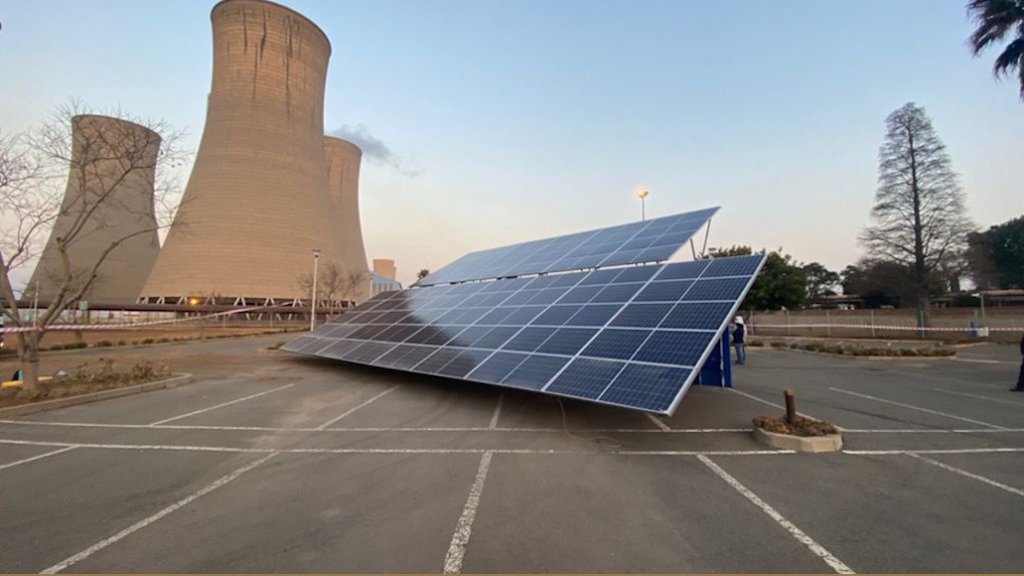

Where the buck stops: Komati was meant to show what the just energy transition should look like on the ground, and our PAIA journey showed how hard it is to see the deals behind it. Better requests helped; institutional culture mattered even more. Photo supplied

What we learned

This research reaffirmed what many journalists and civil society actors already know: while PAIA provides a legal framework for accessing public-interest information, its implementation often falls short.

The process highlighted that timing and persistence are critical. Repeated follow-ups were often the only way to obtain even the most basic responses, exposing a system that rewards tenacity rather than transparency.

It also became clear that well-crafted, specific requests, especially those referencing obligations of state-linked entities or the public-interest override in Section 46, prompted more serious engagement.

Institutional culture played a major role in determining compliance. Eskom’s partial cooperation contrasted sharply with the resistance from private IPPs, suggesting that adherence to PAIA depends as much on organisational norms as on legal duty.

Capacity constraints further shaped outcomes, with delays and non-responses frequently stemming from the absence of dedicated information officers or proper internal systems, particularly within municipalities and smaller companies.

Overall, the process yielded valuable contextual data and opened new lines of communication, but fell short of achieving full transparency.

A just cause: For Abongile Nkamisa of Open Secrets, access to information isn’t bureaucracy, it’s environmental justice. Without it, she said, communities are shut out of decisions that shape their futures. Photo supplied

Why access matters

Access to information in the public interest, such as information about public land leased for private projects, is “critical”, according to Abongile Nkamisa, a lawyer at Open Secrets. “It allows organisations and citizens to hold decision-makers accountable, promote transparency, and ensure that public resources and policies serve the common good,” she said.

“PAIA is meant to enable the public to access critical information efficiently, fairly and without undue obstruction, so that public oversight and informed debate are genuine and possible.”

Access to information is not a bureaucratic exercise; it’s the foundation of environmental justice.

Land and energy decisions shape livelihoods, displacement and economic opportunity. When these deals are negotiated behind closed doors, the people most affected – often rural and low-income communities – are excluded from decisions that determine their future.

As journalists, pushing for access to information allows us to expose inequities, connect the dots between policy and lived experience, and hold power to account. Without documentation, it’s impossible to verify claims about local benefits, job creation, or “just transition” outcomes.

The Access to Information Network (ATIN)’s 2024 report on Access to Information in the Climate, Energy and Environmental Space echoes our findings. It shows that environmental and energy-related PAIA requests are routinely blocked by the same barriers #PowerTracker encountered: overuse of confidentiality exemptions, delayed responses and lack of proactive disclosure.

After meeting with the ATIN and reading their report, we learned that our experience is far from unique. This led us to ask, is this behaviour part of a national pattern of secrecy around climate and energy governance, and why is it so commonplace?

In the public interest: #PowerTracker will continue to liberate data on renewable energy land leases across South Africa. Photo: #PowerTracker

What comes next

Each PAIA request, even when denied, builds a trail of accountability. The more systematically we track the responses, the clearer the patterns of obstruction – and the stronger the case for reform.

Although we were unable to access copies of actual land lease agreements, we were able to get hold of templates of a power purchase agreement (PPA) with Eskom, and an implementation agreement with the Department of Mineral Resources and Energy.

Going forward, the #PowerTracker team plans to strengthen its approach to access-to-information work by refining future PAIA requests explicitly to invoke Section 46 – the public-interest override – as well as the disclosure duties of state-linked entities. Strategic appeals will be pursued where refusals occur, drawing on relevant case law and using oversight bodies such as the Information Regulator to reinforce accountability.

At the same time, we will leverage media visibility to link transparency more clearly with public accountability in the energy transition. Maintaining our centralised database of all requests, outcomes and follow-ups helps track trends across the renewable energy sector and identify recurring barriers to disclosure.

Collaboration is also key. By working with partners such as the ATIN network, our aim is to advocate for broader, systemic reforms to South Africa’s access-to-information regime, ensuring that transparency becomes the norm rather than the exception.

Lessons learnt: Although Red Rocket Energy declined to answer our PAIA request, we learnt some important lessons as part of the rejection process, and will keep pushing IPPs to make land lease agreements public. Photo: Red Rocket Energy

Why we keep pushing

Every denied request tells a story: of institutions still learning (or refusing) to operate in the open, of information systems that serve bureaucracy over accountability, and of a democracy still finding its way toward full transparency.

For journalists, PAIA is not just a tool – it’s a test of endurance and purpose. The process may be slow and frustrating, but it lays the groundwork for future breakthroughs. Each piece of correspondence, each partial disclosure and each refusal adds to the broader evidence base that will, eventually, make secrecy unsustainable.

The right to know is the first step toward the right to a just, equitable and truly transparent energy future.

Our recent PAIA experience demonstrates that systematic, persistent and publicly visible use of access-to-information laws remains essential to unlocking the opaque structures of South Africa’s renewable energy transition.

The struggle for openness continues – and we’ll keep pushing.

Roxanne Joseph is project manager at the Oxpeckers #PowerTracker project, which is supported by the African Climate Foundation’s New Economy Hub

You can find a data on renewable energy land leases in South Africa under out Get the Data section here, and an easy tutorial on how to use the #PowerTracker data-driven mapping tool here