18 Jul The Boegoeberg Blues: A small Nama tribe holds the key to the Orange Oil Basin’s future

A landmark 2003 ruling by the ConCourt in favour of the Richtersveld community has made the still-impoverished Nama people the gate-keepers of the government’s ambitious plans to turn the Northern Cape into an energy and mining hub.

Investigation and photos by John Grobler

Boegoeberg, located about 10km south of Alexander Bay and site of the Richtersveld community’s ancestral graveyard. It is also the site for a planned industrial mega-park and new deepwater port to service the Northern Cape mining industry and off-shore oil and gas exploration activities in the Orange Basin. Photo: John Grobler

The small Nama clan of the Richtersveld and their ownership of a critical swathe of the Namaqualand’s northern-most coastline has become the single-biggest obstacle to the South African government’s ambitions to tapping the off-shore Orange Basin oil and gas reserves in line with the BRICS agenda.

Specifically, it is their ownership of the Boegoeberg area and adjoining bay earmarked for a new R10 billion deep-water port that gives them the whipping hand over the ANC government’s Integrated Resources Plan (IRP) to exploit the Northern Cape’s mineral resources and transform the Northern Cape into a mining and mineral processing Mecca.

And with the off-shore exploration now picking up pace – Shell plans to sink 40 wells in their Northern Cape Ultra Deep block over the next five years, for example – the pressure is piling up on the government to come to the table.

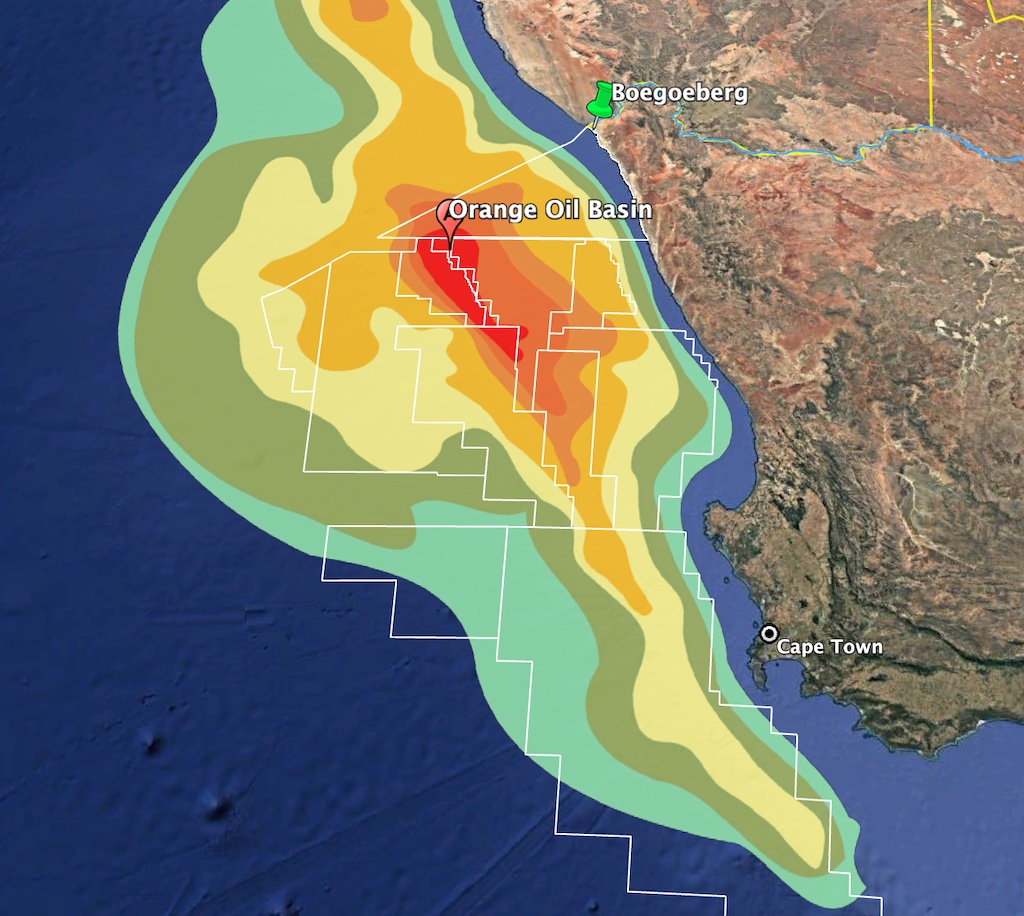

The off-shore Orange Oil Basin is estimated to contain potentially at least 11-billion barrels of light crude and up to 8.7 TCF (trillion cubic feet) of natural gas.

Below: Individual blocks and the rights-holders to the Petroleum Exploration Licences (PELs – Namibia) or Exploration Rights (ERs – South Africa). Datavisualization: Roxanne Joseph

“My personal opinion is that whoever wants to deal with us will have to do so on our terms,” said Kaptein Gert Links in Kuboes, a small settlement of about 2,000 people about 60km inland and 20km south from the Orange River, and home to the Richtersveld traditional authority.

“I might be sitting here in the most remote part of the country, but we know what is going on,” said the great-grandson of Kaptein Paul Links, the first officially acknowledged leader of the Richtersveld Nama whose grave lies on the southern slope of the Boegoeberg with 25 others.

Kaptein Gert Links, great-grandson of Kaptein Paul Links, who is deeply concerned over the potential impact on this rural community that the oil and gas industry would have. The younger people will all leave to look for jobs in Springbok and Port Nolloth, and the Richtersveld settlements like Kuboes where he lives will eventually die for a lack of people, he fears. Photo: John Grobler

The picturesque little village of Kuboes, seat of the Richtersveld traditional authority. A former mission station nestled among the foothills of the surrounding Khubus Mountains, it is still impoverished even though the community now owns 49% of the joint diamond mining venture at Alexander Bay with state-owned Alexkor. Photo: John Grobler

A typical Namaqualand zinc house that was first build by colonial-era diamond and copper miners somewhere along the coast and later rebuilt here in Kuboes, according to local residents. Photo: John Grobler

A faint rainbow falls over the Kuboes valley below the Khubus Mountains of the Richtersveld. After years of crippling drought, the area experienced heavy rains recently that damaged the local infrastructure, washing away roads and bridges. Photo: John Grobler

Landmark ruling

That small graveyard was the single-most important piece of evidence that convinced the Constitutional Court and the Supreme Court in a landmark 2003 ruling to recognise their 1998 land claim against state-owned diamond mining company Alexkor, he confirmed.

But after 18 years of official stone-walling and foot-dragging to implement the terms of the final Deed of Settlement signed on October 10 2007, the Richtersveld people have run out of patience, he warned.

Crucially, South Africa’s two apex courts found that this communal ownership was not limited to the surface of the land, but also encompassed all its natural resources, including the rich alluvial diamond deposits that would become the catalyst for the community’s dispossession.

This clear break with the colonial-era legislation and practices to dispossess indigenous people of their customary ownership of mineral rights as integral to their land rights placed the Richtersveld in the position to lay claim also to the vast oil and gas resources of the off-shore Orange Basin, Links said.

However, with no knowledgeable experts in their own community to negotiate such technically complex agreements, the Richtersveld people were at a major disadvantage, as they had since learnt in their bitter experience of co-ownership of their Alexkor diamond mining joint venture with the government.

Heavy excavators on one of the new diamond mines that have sprung up along the southern banks of the Orange River in the Richtersveld community’s communal lands. The community lacked the experience and knowledge required to negotiate such mining contracts – and is completely at sea when it comes to the off-shore oil and gas exploration rights, said Kaptein Gert Links. Photo: John Grobler

The former Alexkor’s now-defunct Alexander Bay diamond processing plant and workshops stand idle and empty, after the best diamonds have long been mined out. This has made any further mining unprofitable at best and a massive environmental liability, an experience the community does not want repeated in respect of the nascent oil and gas industry. Photo: John Grobler

A typical sight in the area of a former diamond mine along the Orange River that was abandoned and left un-rehabilitated after the regional diamond mining industry collapsed in the wake of the landmark ConCourt ruling that ruled this was communal land and had to be returned to the still-impoverished Richtersveld community. Photo: John Grobler

The derelict Alexander Bay cemetery and, beyond it, the green banks of the Orange River exiting into the Atlantic Ocean. The other, more important cemetery containing the graves of Kaptein Paul Links is located within restricted diamond area and not publicly accessible. Photo: John Grobler

Industrial zone

As result, they were being sidelined and ignored by the government: TransNet, who is to develop Boegoe Bay into a major hub for servicing the off-shore oil fields and establish a massive new industrial zone on the gravel plains surrounding Boegoeberg, was simply ignoring them in laying out the power-line and pipeline corridors across their territory, he said.

In his last meeting with the TransNet officials, they told him that the state would simply expropriate whatever land they needed for Boegoe Bay, taking unfair advantage of their own lack of knowledge of the value of whatever lay underneath that land, he said.

This high-handed approach violated both the letter and spirit of the 2003 ConCourt ruling and left the community deeply suspicious of the government’s agenda, Links said.

“There is not much goodwill left among the community in our negotiations with them,” he said. “Whoever wants access to Boegoe Bay will have to give us iron-clad legal guarantees of recognising our land rights and access in perpetuity to the Boegoeberg grave site.”

“We are not refugees on this land, we’re the original inhabitants who cannot be legally ignored,” he cautioned. “The community has not made any decision yet” about the state’s plans for Boegoe Bay, he warned.

Was this why the proclamation and transfer of Alexander Bay into a local authority was still not finalised and why the pay-outs of individual compensation as final financial settlement of R190-million in damages awarded by the ConCourt was still being delayed?

Final verification of the about 4,500 beneficiaries’ bank account details was completed in early July and the pay-out of about R30,000 each would hopefully commence soon, Links said.

Resident Jason Townsend digging up the old Port Nolloth fishing harbour’s slipway in the hope of finding old copper and brass nails to sell in order to survive. Too often, valuable collector’s items end up being sold and melted down for scrap, he said, pointing to where they had found old ox-wagon wheels that suffered a similar fate. Photo: John Grobler

Above and below: Local services have all but completely collapsed in the wake of the post-2003 economic down-turn, with waste management taking a back-seat, as can be seen at the Port Nolloth Municipal solid waste disposal site. Photos: John Grobler

Environmental damage

As for the rest, that happened before his election as traditional leader earlier this year and the trustees of the Common Property Association, a body created to manage the Alexkor assets they inherited under the 2003 ruling, would have to answer for that, he indicated.

“The land speaks for itself,” he said in reference to the enormous environmental damage that a century of diamond mining had left behind.

The landmark 2003 ruling as an act of restitutive justice had unintended if foreseeable economic consequences for everyone else in Namaqualand as it forced Alexkor to cease all mining operations and lay off about 1,800 workers with immediate effect.

This had a devastating impact on the other Namaqualand communities where diamond mining had been the lifeblood of the regional economy since the 1920s.

Diamond-mining towns like Hondeklipbaai, Koiingnaas, Kleinzee and Kommagas became virtual ghost-towns as the Namaqualand diamond economy imploded overnight – and just never recovered.

The now-silent Koiingnaas diamond mine, first sold off with all environmental liabilities by De Beers to West Coast Resources who then went bankrupt, leaving any effort at rehabilitation in permanent limbo. Photo: John Grobler

A row of fisherman’s houses in the port area of Port Nolloth, where artisanal fishing has become a thing of the past due to the damage that the coastal diamond mining caused to the fish-breeding areas. Photo: John Grobler

A misty day over the small Port Nolloth harbour, too small and too far away to service the needs of the Orange Basin. With international diamond prices now also in the doldrums, even the diamond-pumping boats remain at anchor. Photo: John Grobler

Port Nolloth’s former fishing harbour, where hope for a better future depends on the uncertain implications of the off-shore oil and gas industry for which the local population is ill-prepared. Photo: John Grobler

Legal limbo

The uncertainty of this legal limbo has discouraged any other private investment to boost tourism and attract visitors to the incredibly rich and diverse Richtersveld and Namaqua National Parks, home to the unique and endemic succulent Karoo biome, members of the local business community said.

Unemployment among the youth is now about 95%, said former unionist Carisa Soudens, with many now resorting to poaching rare succulent Karoo plants from the Namaqua National Park to make ends meet. “You can’t blame them, there’s nothing else here,” she said.

Oryx in the Namaqualand National Park, transformed into a flower wonderland by recent heavy rains that also washed away bridges and roads – damage that locals say will not be fixed for years to come. Photo: John Grobler

The wide coastal plains of Namaqualand from Wildeperd Pass in the Namaqualand National Park, where the primordial Great Karoo River formed a river-mouth several hundred kilometres wide. Photo: John Grobler

The unique succulent Karoo landscape around the Nama settlement of Concordia, now fighting for control over their land in face of copper-mining interests. Photo: John Grobler

Boom-and-bust

The 2003 ConCourt ruling also created a legal loophole for the likes of private-sector diamond miner TransHex and Alexkor to abandon their legal responsibility to rehabilitate former mining sites – a repeat of the copper mining industry’s boom-and-bust cycle of the 1970s, said retired mine rehabilitation expert Dudley Wessels in Koiingnaas.

“That’s the greatest tragedy of Namaqualand: nothing of the billions in mining profits made here was ever re-invested locally,” he said. While he welcomed the prospect of an off-shore oil bonanza, he feared the Orange Basin oil rush would end the same way – but with far worse environmental consequences, once that resource was also depleted.

In hindsight, the 18 years of political foot-dragging by the national government in implementing the 2007 Deed of Settlement seemed a deliberate ploy to create a political and legal vacuum in terms of ownership of mineral rights and open the door to legalised land-grabbing by actors aligned to the IRP agenda, local people interviewed over course of a week said.

In the following years, wild-cat diamond mining became rife as foreign illegal miners known as the zama-zamas and fortune-seeking diggers from the North West took over the former Alexkor mining areas.

The worst plunderers have been the North-West diggers doing their own “artisanal mining” with heavy excavators and other industrial equipment, and often within town limits, said Pieter Blackie, a conservation-minded property developer in Kleinzee.

Poorly-controlled and un-supervised diamond mining in the town-lands immediately south of Kleinzee, digging up areas that previously had been rehabilitated. Photo supplied

Evidence of heavy beach mining outside Kleinzee, where diamond miners use heavy equipment to suck out all the diamond-bearing gravel down to bed-rock level, wiping out whatever form of life may have existed here. Photo: John Grobler

Alexkor itself has been a culprit: in 2022, it was criminally charged by the Green Scorpions for building illegal coffer dams that have deeply damaged the local artisanal fishing industry.

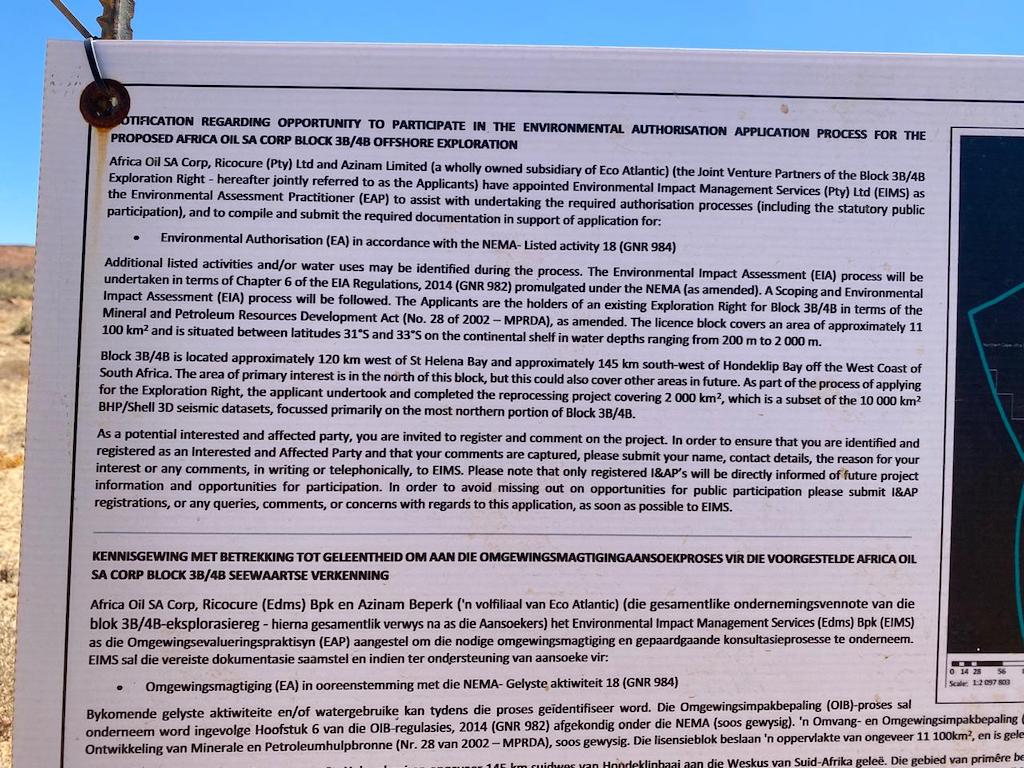

Research indicates statutory public notifications in terms of the Environment Conservation Act (1998) of public meetings on mining licence applications and related developments are being done in a manner that may meet the bare letter of the law, but not its wider intent of ensuring public participation.

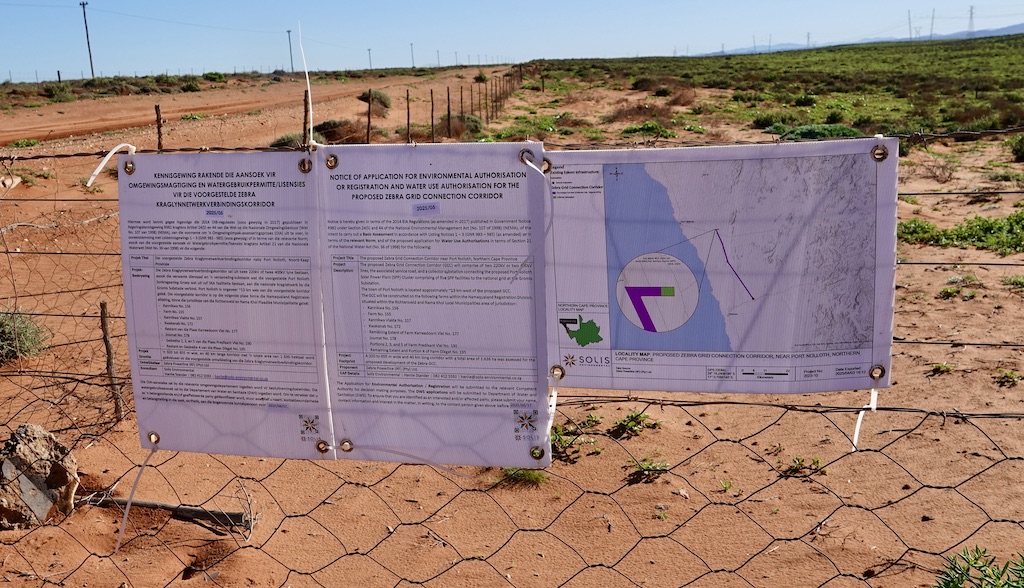

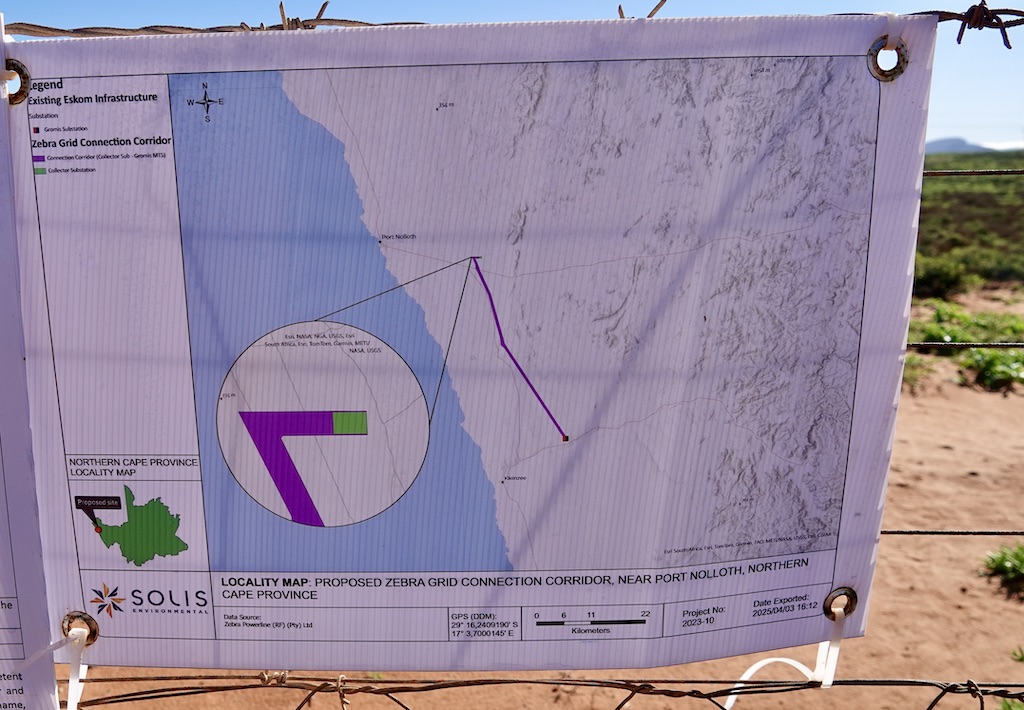

For example, 10km outside Port Nolloth on the Kleinzee road, an official EIA Notice for water usage was pinned to a farm fence – a common practice here. It notified the public that the Zebra Grid Connector Corridor, measuring 320m to 655m in width across 40km of eight farms, was to be created here for connecting the five solar production plants planned for Port Nolloth to the national grid.

Environmental Impact Assessment notices are typically fixed to farm fences or pegged into the ground, with little chance of being noticed by the general public. This one is for the Zebra Grid Connector Corridor, 10km outside Port Nolloth. Photo: John Grobler

Eight farms in this area will have corridors of 300m to 600m wide and 40km in length bulldozed to accommodate the Eskom infrastructure, and the land-owners have little to no say on whether this should be allowed to proceed. Photo: John Grobler

EIA meetings

But in Port Nolloth in July 2025, no one was aware of this. Venues for public EIA meetings are often changed at the last moment to minimise local opposition to questionable mining licences issued by the Department of Mineral Resources, local residents said.

As for any objections, those have to filed in writing and in the case of oil exploration rights, have to be accompanied by a R500 fee, according to one such notice posted on the Richtersveld Municipality’s notice board on behalf of Tosaco, who holds the rights to one of the potentially most lucrative off-shore Orange Basin oil blocks.

Read the small print – if you happen to notice the sign posted along the Hondeklipbaai road. This is the EIA notification for exploration of the off-shore oil blocks 3B/4A – but who would notice it when driving past? Photo contributed

Now you see me, now you don’t: EIA notice for off-shore oil block 3B/4A. Photo contributed

Meanwhile, on the streets of the Namaqualand towns, there was a heavy police presence. Restaurants are checked weekly for any illegal abalone or crayfish, the only other Diamond Coast products that could earn the destitute local people any cash.

The over-all effect was chilling: a selective show of force in the debasing of the environment, while systematically undermining the local traditional authority’s writ and the rule of law.

John Grobler is a Namibia-based associate at Oxpeckers Investigative Environmental Journalism. This is the second in a series of Oxpeckers #PowerTracker transnational investigations that interrogates the environmental, socio-economic and political impacts that the Orange Basin Corridor oil and gas developments could potentially bring. Find the first investigation here