08 May Where is Zimbabwe’s cyanide queen?

Police are keeping mum about the extradition of Li Song, wanted in connection with the use of poison in illegal wildlife trade. Pamenus Tuso investigates

An undated photograph shows Li Song, a Chinese national wanted by authorities in connection with the illegal importation of cyanide, a toxic chemical that has been used to poison wildlife in Hwange National Park, Zimbabwe. Photograph supplied

Zimbabwe’s national police force appears reluctant to pursue Li Song, a Chinese national allegedly at the centre of a poaching network that uses the deadly chemical cyanide to kill animals in the country’s game reserves.

Li was arrested in 2024 by the Zimbabwe Anti-Corruption Commission (ZACC) for allegedly importing large quantities of cyanide fraudulently and storing the toxic substance in unsafe locations.

According to court records, in August 2024 Harare magistrate Dennis Mangosi issued a warrant for her arrest after Li failed to appear in court, leading to suspicion by authorities that she could have escaped and returned to her home country, China. The case involves alleged misrepresentation to the Zimbabwe Revenue Authority over the importation of sodium cyanide, a salt of cyanide that turns into a toxic gas when it interacts with water.

Li skipped bail and is evading prosecution. Meanwhile, wildlife conservationists are asking hard questions: how did a high-profile foreign national wanted by the courts manage to skip the country undetected? Why are the police dragging their feet in updating the public on law enforcement efforts? And most damming of all – why authorities appear to be reluctant to pursue the wanted suspect.

In a telephone interview, National Prosecution Authority of Zimbabwe spokesperson Angeline Munyeriwa said, “The docket for Li is now in the hands of the police. We forwarded the warrant of arrest to the police for action. Our role is to prosecute only.”

Despite concerted efforts to obtain an update on progress made in executing Li’s warrant of arrest, police spokesperson Commissioner Paul Nyathi failed to respond to questions about whether she had fled the country, the Zimbabwe Republic Police has engaged Interpol or other international agencies about the case, and there are broader efforts by law enforcement to track and prevent illegal importation of hazardous chemicals such as cyanide which is used in poaching activities.

The inquiries, first submitted on March 31, were acknowledged by officers in Nyathi’s office, who repeatedly assured that a formal response would be forthcoming, but this was not done by the time of publication.

Communications manager of the ZACC, Simiso Mlevu, also did not respond to questions submitted in late April about the matter. Considering the unit – a constitutional body formally established in 2013 whose functions include investigation, prosecution and punishment of corruption and other criminal conduct – was responsible for Li’s arrest, this reporter sought clarification on whether it has the authority to execute a warrant of arrest independently, and whether it had engaged Interpol or other relevant law enforcement bodies.

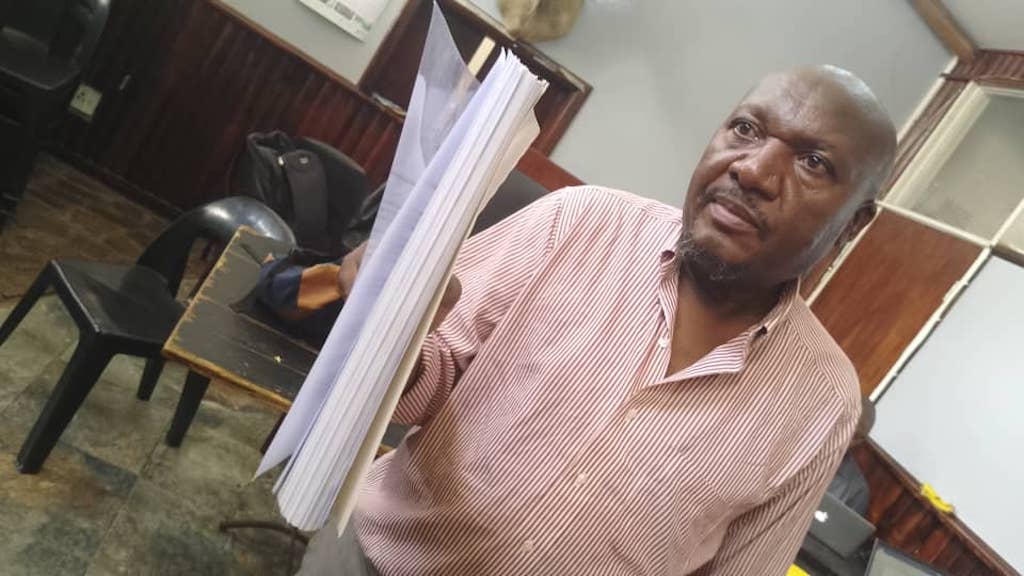

The journalist with a dossier of court documents related to a range of allegations made against Li Song, including wildlife crimes, fraud, forgery, theft of trust property, money laundering and even attempted murder. Photo supplied

Official protection

According to court documents, Li was born on January 20 1972 in Henan province in central China. She arrived in Zimbabwe in 2003. She has been reported to be linked to top government officials (names provided) who allegedly provide her protection against a litany of cases she faces in a country ridden with corruption. In its 2024 corruption index survey, Transparency International ranked Zimbabwe number 158 out of 180, countries making it one of the world’s most corrupt countries.

According to sources who were closely linked to her, Li arrived in Zimbabwe under modest circumstances and worked as an official interpreter for a Chinese construction company, China First. The company had numerous contracts in the country. The sources say Li would claim that her father was a high-ranking general in the Chinese army, whom she allegedly claimed supported her in her ventures.

We further established from the same sources that Li later purchased China First after it had gone under the hammer. The interpreter had transformed into a businesswoman, acquiring various properties, including upmarket houses in Beijing and Henan.

Our investigations established that she used to frequent Sammy Levy village, an upmarket mall in the capital, Harare, which is often patronised by socialites, businesspeople and diplomats. This, according to research, was at the time she stayed in the same neighbourhood at number 82 Piers road with her son.

“Li used to frequent Sammy Levy Village gym and the Golden Peacock Restaurant in Borrowdale where she networked with ease. She would at times be accompanied by government officials and she became a centre of attraction,” said a source privy to her lifestyle who preferred not to be named in the story.

A drinking point suspected of being targeted by poachers who lace water sources with cyanide in Hwange National Park, Zimbabwe, on April 5 2025. Photo: Pamenus Tuso/SA | AJP

Cyanide case

According to court documents, the 2024 cyanide case involved DGL9 Investments Pvt Ltd, a mining company based in Inyathi in Zimbabwe’s Matabeleland North province. Li is a former director of the company and her co-accused, Bernadette Mukuku, is a former employee.

According to state papers, Li and Mukuku falsely represented to the Zimbabwe Revenue Authority that a consignment of sodium cyanide and hydrated lime they imported from Mauritius was conducted by the company, whereas it was done in their personal capacity. This enabled them to avoid paying customs duty of US$40,000. Police investigations have pointed to the use of the two chemicals in wildlife poaching in the country.

The case was initially heard at Bulawayo Magistrates’ Courts – case number BCR05/03/24 – before it was transferred to Harare under unclear circumstances.

Cyanide poisoning has been a significant threat to elephants in Hwange National Park, Zimbabwe’s biggest nature reserve with an estimated 50,000 elephants.

In 2013 poachers killed more than 300 elephants by poisoning salt and water pans with the lethal chemical. Over the years since incidents have continued, with 14 elephants poisoned in October 2015 in three separate incidents within the park and nearby Deka Safari area.

The decomposing carcass of an elephant believed to have succumbed to drought conditions in Hwange National Park on November 27 2024. Photo: Pamenus Tuso/SA | AJP

Powerful individuals

Elizabeth Valerio, a Hwange-based conservationist and leader of opposition political party United Zimbabwe Alliance formed in May 2021, recalled how trains used to stop randomly along the railway line in the national park to pick up ivory. She suspects that the ivory came from elephants killed through cyanide poisoning, and that the scheme had the backing of powerful individuals.

“Cyanide poisoning has been going on for over a decade. Some of these activities had far higher authorities behind them,” she said.

“The use of poison in illegal wildlife trade is always a concern because not only is it a silent and effective way of killing animals, but the knock-on effects within the ecosystem are large,” said Nathan Webb of the Wildlife Conservation Coalition, an association of organisations whose mandate is to provide a collective and united voice for conservation in north-western Matebeleland.

Proposed changes contained in the Wildlife and Parks Amendment Bill will include punishment for poachers who use poisons, Webb said.

“This is not something that has previously had a charge or a penalty. The biggest deterrent has got to be the penalties and fines and the punishment that people get when caught with such issues,” he said.

Elephants and a calf at a watering hole in Hwange National Park on November 27 2024. Li was allegedly involved in the controversial export of 100 elephant calves from Zimbabwe to China in 2017. Photograph by Pamenus Tuso/SA | AJP

Elephant exports

A leading wildlife conservationists in the Hwange area who asked not to be named for security reasons said Li was also involved in the controversial export of 100 elephant calves from Zimbabwe to China in 2017, and that she masquerades as a close associate of the late president Robert Mugabe’s family.

Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority spokesperson Tinashe Farawo was reluctant to comment on these claims. “The issue of Li Song is a matter before the courts and we cannot be seen to be commenting on issues before the courts,” he said.

He however confirmed that between 2018 and 2019 Zimbabwe exported elephants to China. “The last time we exported elephants was in fulfilment of a trade agreement between the two countries,” he said.

There has so far been no response to inquiries sent in mid-April to Li via email. Questions included whether she intended presenting herself to the authorities in connection with case number BCRO5/03/24, whether she was aware of the warrant of arrest issued against her, and whether she wanted to comment on the allegations against her.

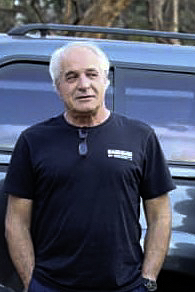

An undated photograph of Francesco Marconati, Li Song’s former boyfriend and business partner, currently involved in a series of contentious legal disputes with Li Song. Photograph supplied

Other allegations

According to a dossier of court documents in our possession, Li has faced other allegations beyond wildlife crimes, including fraud, forgery, theft of trust property, money laundering and even attempted murder. Despite the gravity of the accusations, the complainants say the cases have not been pursued by authorities.

The documents show that Li, who had been in a business partnership with her former boyfriend Fransesco Marconati, was removed as director of Eagle Italian Shoes Pvt Ltd and Eagle Italian Leather Pvt Ltd in October 2021. Marconati filed a case in November 2021 accusing Li of the unlawful and forced sale of shares in the two companies.

In May 2022 he opened another fraud and forgery case at Bulawayo Central Police Station, accusing Li of forging an invoice from South African chemical supplier Cure Chem Investments. The case was later moved to Harare after no action was taken by Bulawayo police.

Marconati also accuses her of illegally transferring more than US$809,000 from Eagle Italian Shoes and other Marconati-linked companies to offshore entities. This allegedly involved movement of funds through Ecobank Zimbabwe to a Mauritius Commercial Bank account. The matter was also reported to the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe, according to the documents in our possession.

As a follow-up to what he believes to be sluggish progress in addressing his complaints, in April 2024 Marconati lodged complaints with the ZAAC, the Commissioner General of Police and the Prosecutor General.

In January 2024, Marconati wrote to Prosecutor General Loice Matanda Moyo, requesting a meeting to discuss evidence that Li had used her Mauritius-based company, Jacaranda, to siphon large sums from Zimbabwe. He accused her of breaching trust and covering her tracks with help from “unnamed individuals”, vowing continued efforts to recover the lost assets, according to the court documents.

• Editor’s note: Post-publication several readers alerted us to media reports in September 2024 that Li had been deported with her son for being “a national security threat”. According to the lawyers involved in the cases against her, these reports were based on “hearsay” and there has been no official confirmation of her deportation. Police and other authorities contacted for this article did not respond to questions about whether she had left the country, and whether extradition proceedings were being executed.

• Track data on wildlife and other environmental crimes across the globe on the Oxpeckers #WildEye tool

This investigation was produced with support from the Southern Africa Accountability Journalism Project (SA | AJP), a partnership between the Henry Nxumalo Foundation, Oxpeckers Investigative Environmental Journalism and Viewfinder Centre for Accountability Journalism. It was funded by the European Union. Its contents are the sole responsibility of SA / AJP, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union.