30 Apr Namibia plans to become an energy powerhouse – but is it realistic?

Namibia’s new government is pinning its economic hopes on the development of the Orange Oil Basin to create a quarter of a million new jobs. What does this mean for a small, open economy that is not quite ready yet for a major oil rush? John Grobler investigates

Historically marginalised: the Nama people of the arid plains of Kharas and the Northern Cape are organising themselves as a political force that will shape how the oil and gas resources are to be utilised. First step will be to insist on equity in the oil riches to be able to develop themselves. Photo: John Grobler

Fifty years after Chevron first struck gas off its southern Atlantic coastline in 1974, Namibia is about to embark on an ambitious plan of creating an industrialised economy over the next five years of mining and local processing in Special Economic Zones, fuelled by natural gas from the off-shore Kudu Gas Field and the Orange Basin.

If all goes according to plan, the Namibian government plans to industrialise the country’s under-developed southern and coastal regions into mining meccas, turning the Walvis Gas Port into the biggest regional energy hub and Namibia into a major African energy player as exporter of electricity, oil, gas and – somewhat contradictory – green hydrogen and ammonia. (See our investigations into GH2 in Namibia here.)

All this would add up to a quarter of a million new jobs by 2030, Namibia’s newly elected President Netumbo Nandi-Ndaithwa hopes.

To achieve this, she has streamlined the Namibian government by reducing the number of ministries from 22 to 12, and created a new Directorate of Petroleum Affairs reporting directly under the Office of the President.

“The oil and gas sector holds the potential to transform our economy in the next five years. This new industry requires close monitoring, hence my decision to place it in the Presidency,” Nandi-Ndaithwa told Namibia’s Parliament in her maiden state of the nation address on April 24.

The former Ministry of Trade and Industry has been split up between an expanded Ministry of Mines, Energy and Industrialisation under new Deputy Prime Minister Natangwe Ithete, while the Directorate of Trade now falls under the expanded Ministry of International Relations and Trade, run by Namibia’s former ambassador to Vienna, Selma Ashipala-Mushavyi.

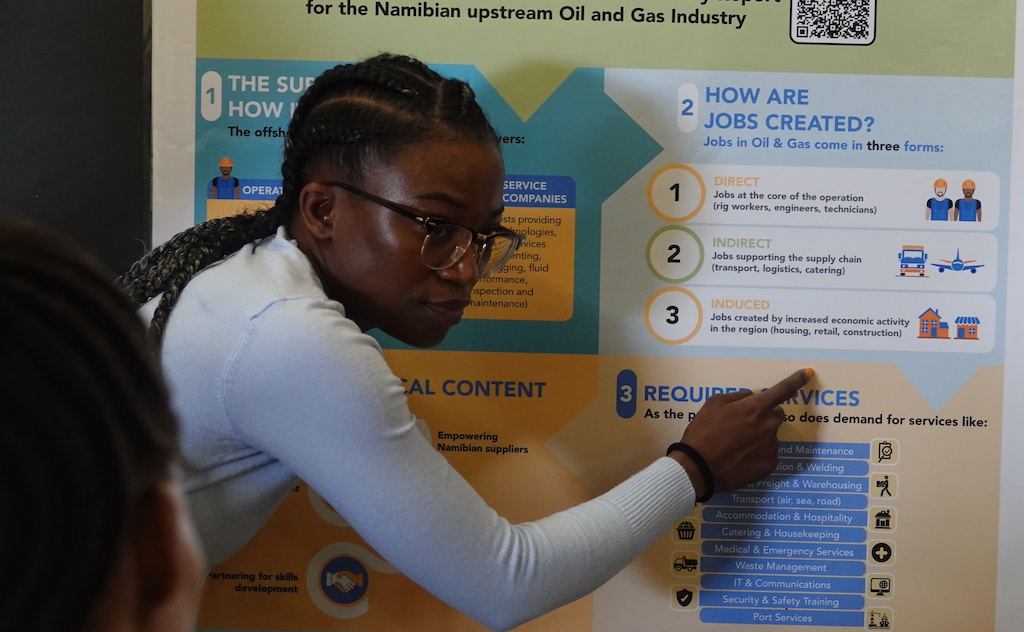

Job creation: An environmental and social impact consultant explains to members of the Bethanie community where the best prospects for employment in the Orange Oil Basin industry will be – in housing, retail and construction, as no one here is qualified for the highly specialised oil industry positions that will become available. Photo: John Grobler

New jobs

But how realistic is this target of 250,000 new jobs really?

On the positive side, exploration has dramatically picked up pace of late. Over the next five years, TotalEnergies plans to sink up to 40 new boreholes in the deep offshore Venus Prospect, located 300km off-shore at depths of 3,000m to 3,200m of water.

Shell, which suspended its USD$400-million exploration programme in Namibian waters late last year, instead plans to drill up to 40 holes next door in South African waters immediately adjacent to their Namibian Jonker-IX prospect which they deemed uneconomic.

Meanwhile, BW Energy is to sink four more wells in Kudu Gas Field immediately north of the TotalEnergies and Shell oil blocks this year, while Galp Energia also is planning four to six new wells in their oil block that surrounds the Kudu Field to the west.

If successful, TotalEnergies and Shell both plan to use floating production storage and offloading (FPSO) platforms – basically giant floating refineries – 300km out at sea that will transport the oil products by ship to either Lüderitz or Walvis Bay.

Limited water supplies: The isolated town of Lüderitz is entirely dependent on the Namib aquifer for water supplies, and the expected future influx of job-seekers can be expected to put this limited resource under severe strain. Photo: John Grobler

Full production

But none of this will create 250,000 new jobs: TotalEnergies, which has had a permanent presence in Lüderitz since 2023, estimated that going into full production would at best create 7,000 new jobs.

Of those, only 600 will be in the oil industry itself, another 600 in the oil services industry, while the financial injection of USD$10-billion would induce the creation of another 5,800 jobs in the related accommodation and logistics sector, according to TotalEnergies.

That may be a conservative estimate in terms of the socio-economic impact. Howard Head, who has been running a marine diamond mining company since the early 1990s out of Lüderitz, said they calculated that every job on each of his eight diamond-dredging boats supported as many as 18 other people.

Lüderitz Mayor Phil Bilhao thinks the job growth will come from a plan to expand the small local port to accommodate the oil tankers and service vessels for the Orange Basin, and from BW Energy’s plan to build a new 400MW gas-fired power plant that will use gas piped in a 300km-long undersea pipeline by BW and Galp.

A bone of contention: The Nama clans of the Kharas, Hardap regions and the Northern Cape province are asserting their ancestral rights to have a direct say in developments such as the expansion of the Lüderitz port. Photo: John Grobler

Ancestral lands

Any onshore developments would have to obtain the political support of the Nama people, whose former ancestral lands stretched the 500km of arid plains and isolated mountains between Gibeon and Lüderitz in Namibia, and Springbok and Port Nolloth in South Africa’s Northern Cape.

Having now successfully blocked the expansion of the Lüderitz port’s manganese shipping facilities, the Namas are becoming more militant in their approach in terms of any industrial development in what can broadly be called Namaland.

“We’re looking for equity,” said Gerson Dausab of the Hardap Regional Council, speaking on the sidelines of a Nama Traditional Authority summit held in Lüderitz in early April.

“Wherever oil is discovered in Africa, it too often leads to conflict because the industry always develops at the expense of the local community. If they share in the ownership, then this can be avoided because the people can develop themselves at the same time as the industry and not be at the mercy of Big Oil.”

A case of delayed development: The expansion of Lüderitz’s small port is currently being blocked by the Nama objections, and the authorities are now considering alternative sites in the North Harbour (top right area, behind Penguin and Seal Islands), across the bay at Angra Point or 30 km out of town at Elizabeth Bay. Photo: John Grobler

Legal hurdles

Apart from political obstacles, there are also legal hurdles to overcome. For example, Namibia’s outdated maritime and Admiralty laws are in urgent need of updating, said Dr Abisai Konstantinus, a maritime law expert.

Namibia also lacks any form of legislation covering the commercial gas sector, having dropped this aspect completely from the 1992 Petroleum Exploration Act with the aim to update it when necessary at a later date.

But 33 years later, this still hasn’t happened – and as matters stand now, there is no plan to re-introduce the Namibia Energy Regulatory Authority (NERA) Bill this year after it was briefly tabled but then withdrawn from parliament in 2018.

So is Namibia planning to wait for South Africa first to table its own, long-awaited Liquid Natural Gas (LNG) Bill in order to use the same legislation for Namibia?

The larger picture suggests this may well be the case. The Harare-based Southern African Development Community’s Secretariat for all electricity control boards in the SADC region in January 2021 had awarded two new electricity licences in Namibia: a 400MW licence for the BW Kudu Energy Plant outside Lüderitz, and a 600MW licence to Xaris Energy to build a gas-powered plant in the Walvis Bay Gas Port.

Having already constructed a massive LNG jetty at a cost of R7.7-billion between 2015 and 2019 at Walvis Bay that has largely remained a white elephant thus far, signs are that the Namibian focus therefore will be on making this investment pay off first before investing in any other oil-related infrastructure anywhere else.

Ready to drill: A stack of oil borehole casings at TotalEnergies’s stockyard in Lüderitz’s small industrial area, ready to be moved out to the Venus Oil Field drill sites where TotalEnergies will sink up to 40 wells over the next five years. Photo: John Grobler

Oil price

The Namibian government plans to borrow R180-billion to finance all of the above-mentioned plans, according to Nandi-Ndaithwa. But with the oil price falling due to economic turmoil in the global economy as result of the American trade tariff war, the single-biggest question is which international lender has the appetite for this kind of risk at the moment.

So what are the realistic chances of Namibia pulling all this off in the next five years? That, according to the best estimate that could be extracted from TotalEnergies, would all depend on what the new NERA Bill would look like.

But with the NERA Bill (and South Africa’s NERSA equivalent) held back by internal politics, as seen from the Nama demand for equity or else, the development of the oil and gas resources off the southwest African coastline continues to hang in the balance for now.

This is the first in a series of Oxpeckers #PowerTracker transnational investigations that interrogates the environmental, socio-economic and political impacts that the Orange Basin Corridor oil and gas developments could potentially bring.