30 Sep Potential impacts of gas flaring in Soyo, Angola

Journalist Neusa e Silva travelled to Soyo to discover the potential human and environmental costs of gas flaring on the ground

View of the flaring towers from Praia dos Pobres, situated 2.28km from the Angola LNG complex, the largest natural gas exploration investment on the African continent. Photo: Neusa e Silva

Gas flaring associated with oil exploration in Angola has raised significant concerns regarding its detrimental effects on climate change and food security. Environmental experts warn that the practice may be contaminating local soils and water resources while simultaneously contributing to increased regional temperatures. In Soyo, a province in northern Angola, growing questions surround the security of community proximity to gas flaring projects and whether adequate measures have been taken to protect public health and the environment.

Ana Maria (a pseudonym) and her elderly mother, both residents of a neighbourhood near Soyo Municipal Hospital, shared their experiences with our reporter, Neusa e Silva. Although initially hesitant and wary of strangers, Ana Maria eventually agreed to speak about the challenges faced by her community. Soyo, a city in Angola’s Zaire Province, is home to approximately 260,000 people, many of whom rely on subsistence farming and fishing to sustain their livelihoods.

Ana Maria, like many women in the region, supports herself by farming and selling cassava. However, she highlighted the increasing difficulty of farming in recent years, attributing these challenges to two primary factors: rising temperatures and the rapid deterioration of crops.

“In recent years, it has become increasingly difficult to farm,” Ana Maria explained. “The city has been getting noticeably hotter, and the vegetables and tubers in our fields are spoiling even before we can harvest them. This phenomenon has been intensifying for about five years, coinciding with the increased operation of the gas flaring towers nearby. During what used to be the cold season, the temperature hardly drops anymore. Our crops are rotting in the fields long before they should. It wasn’t like this in the past.”

Restaurants at Praia dos Pobres. Photo: Neusa e Silva

Oil production

Located in southwest Africa, Angola is one of the largest oil producers on the African continent. Oil production is the country’s main source of revenue, accounting for around 98% of export earnings and approximately 75% of the Angolan state budget. A significant part of these oil exports come from the provinces of Cabinda and Soyo, where the country’s largest oil exploration projects are located, both offshore and onshore.

When Ana Maria and other interviewees referred to the illuminated towers, they were referring to the two gas flaring towers located in the Angola LNG (Liquefied Natural Gas) project complex, the largest natural gas exploration investment on the entire African continent.

This project is made up of the following national and international oil companies: Sonangol (Angola’s national fuel company with 22.8%), the American company Chevron with 36.4%, the French company TotalEnergies with 13.6%, Azule Energy Exploration (Angola) and Azule Energy Angola Production B.V.

Azule Energy is an autonomous energy company that resulted from the combination of the assets and workforce of BP Exploration Operating Company Limited (“BP”) and Eni International B.V. (“Eni”), each with an equal 50% stake, according to information available on its official website.

The Angola LNG consortium is dedicated to processing and receiving natural gas from different oil exploration platforms, and has the capacity to supply the global market with up to 5.2 million tons of liquefied natural gas (LNG) per year, according to the consortium’s website.

Our reporting team contacted the management of the Angola LNG project to ask about the measures adopted to mitigate possible environmental damage and the impact on the population living near the complex. We were informed that, at the moment, it is not possible to visit the complex or grant interviews.

We also requested an interview with the official entities and the regulatory body, in this case the Angolan National Oil and Gas Agency, to find out whether the country has implemented measures to regulate and control the levels of gas flaring by operators, if any. However, as of the closing date of this report, we had still not received the promised answers.

In addition to Angola LNG’s facilities, Soyo province is home to other oil exploration projects, both offshore and onshore, operated by national and global companies.

Local farmers highlighted the increasing difficulty of farming in recent years, attributing these challenges to two primary factors: rising temperatures and the rapid deterioration of crops. Photo: Neusa e Silva

Land expropriation

Farmers Ana Maria and Helena Vanda Estevão told our reporter that the degradation of their crops began to increase about five years ago. But what is even worse for Ana Maria is that the land where some of the women grow their own food is being expropriated, without any justification.

“Yesterday, they told us to pull up the cassava in 15 days because the land has already been sold,” said Ana Maria. “No one has been able to explain to whom the land we planted was sold. All they say is that the second city of Soyo will rise in the place of these plantations. No one knows who the companies or people are who are selling or buying the land. We do not know if it is the administration that is selling it without informing the people, they have not said anything, nor have they announced anything on the radio or television,” she said.

Another place visited by the reporter was Bubu Island, a small fishing village, where we met Donã, a fisherman who has lived on the island since 2000. Donã shared that in the past, they used to fish in the waters around the island, but now there are almost no fish left.

“We don’t fish here anymore, now we go fishing in the open sea to catch fish. Some use nets, others use lines, in the open sea. But back then, we used to fish here with nets. We used to catch snapper and several other types of fish until 2007. Now, not anymore,” he said.

In a conversation with Angolan family physician Dr. Sandra Gabriela (pseudonym) about the risks faced by Soyo residents due to continuous direct and indirect exposure to gas flaring, she explained that in the short and medium term, exposure to gas flaring significantly increases the likelihood of developing cancer, inflammatory diseases, skin cancer and many other health problems. The burning of gas can also cause headaches, migraines, insomnia and nausea, the doctor said.

“Prolonged exposure can lead to liver damage, birth defects, cancer and even mental health problems,” said Dr Gabriela.

Donã, a fisherman from Bubu Island Donã, told the reporter that now there are hardly any fish left. Photo: Neusa e Silva

Climate risk and regional food scarcity

Experts indicate that gas flaring, associated with oil extraction, has severe impacts on soil contamination, a phenomenon frequently observed in oil exploration areas. In flaring zones, there is an increase in local temperatures, the release of toxic pollutants, and soil contamination. According to the latest Climate Risk Report for the Southern Africa region, the Met Office, ODI and FCDO have warned that the region is on the brink of a devastating famine crisis.

On April 22 2024, CARE, the Council for the Humanities, FANRPAN and the Rural Women’s Assembly reiterated the warning, calling for support from international donors.

To understand the relationship between these phenomena and natural gas exploration activities in Soyo, we spoke to environmental engineer Vanessa Mateus. In addition to our reporter’s on-site research, the journalist also asked an expert whether the gas flaring operations were considered harmful to the environment and human health.

Asked about the effects of gas flaring, Mateus said she was concerned about the safety of the distance between the gas flaring projects in Soyo and Cabinda and the surrounding communities. She noted that “although many projects in the concession phase are destined for areas without communities, agricultural activities or natural conservation areas, the lack of master plans at municipal or land-use planning level contributes to local disorder, bringing communities closer to the companies”.

She added that new neighbourhoods or houses are springing up every day near the companies, partly due to rural migration, as people looking for better living conditions are attracted to the areas where the exploration companies are operating.

Biodiversity is also at risk, she said. “In general, we can consider that there is significant loss and removal of biodiversity, as animals and plants tend to be more sensitive to certain impacts. The effects on air quality and natural watercourses are very difficult to control.”

Pollutants are carried by winds and are no longer just localised; they become regional and even provincial, she explained. “The same goes for leaks into rivers and seas, which are spread by currents and can have local, regional, or even provincial impacts.”

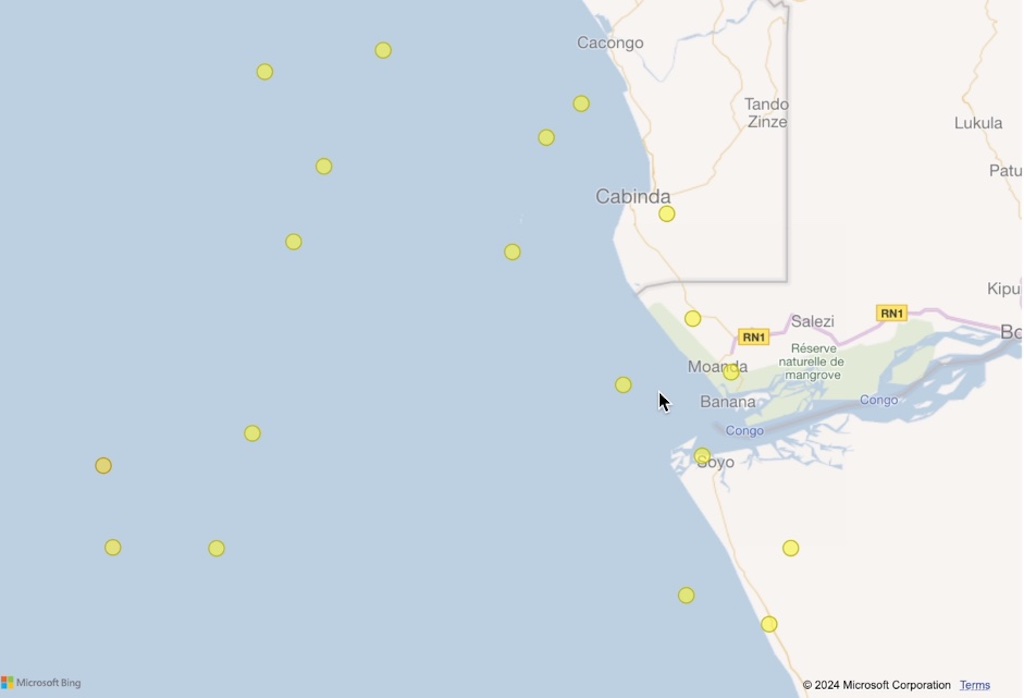

Individual flaring sites – Gas flaring volumes (mn m3/year). Source: World Bank. Graphic supplied

Increased production plans

At the end of last year, Azule Energy and its partners announced the laying of the foundation stone for the construction of the facilities of the New Gas Consortium that will operate in the city of Soyo. The press release, dated October 4 2023, states that “it will be the first non-associated gas project in Angola, with production scheduled to start in 2026, an investment valued at around 2.2 billion dollars”.

On the other hand, Angola LNG recently announced plans to increase its natural gas production. In a recent interview with Jornal de Angola, Angola LNG CEO Amilton Cunha said that the increase was the result of new investments underway, which will allow the company to receive more associated and non-associated gas from offshore platforms. Amilton Cunha highlighted that Angola LNG currently sends more than 50 ships loaded with products to the global market every month, reinforcing its importance in the energy scenario.

The CEO of Angola LNG highlighted the company’s social impact in the province of Zaire, where its social responsibility policy has contributed significantly to the provision of basic services, improving the living conditions of the local population.

Neusa e Silva is an Angolan journalist and international freelance correspondent based in Portugal. This investigation is part of the series “Burning Skies: Behind Big Oil’s toxic flames”, developed by Environmental Investigative Forum, a global consortium of environmental investigative journalists, in partnership with the European Investigative Collaborations network, and their partners Daraj, Source Material and Oxpeckers Investigative Environmental Journalism. This series was supported by Journalismfund Europe