02 Aug ‘We want a say in transition mining’ – DRC communities

Communities living on and working land in the Democratic Republic of the Congo say they are not informed about mining permits for energy transition minerals. Jonas Kiriko speaks to them

Village chief Mulema Bantu: ‘We know that conditions are often stipulated for mining companies, but we know nothing about them or their content.’ Photo: Jonas Kiriko

Subsidiaries of Canadian mining company Ivanhoe Mines received new operating permits in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in 2023, but nearby community members who had to make way for the mines say they were not consulted and had no influence in the process.

“When a company obtains a permit, it only discusses it with a particular landowner without taking into account the opinions of the villagers who live in the area. We know that conditions are often stipulated for mining companies, but we know nothing about them or their content,” said Mulema Bantu, a village chief whose people had to move from their land to make way for Kengere Mining near Kolwezi, an important mining centre for copper and cobalt in southeast DRC.

Kengere Mining is a subsidiary of Ivanhoe Mines and is registered as a private company in the DRC. On April 16 2023 it was granted an exploitation permit to operate a small copper mine of 38 square kilometres that will expire on April 15 2028.

Another Ivanhoe subsidiary, Makoko SA, was granted four connecting exploitation permits for copper on April 16 2023. All four permits cover an area of 424 square kilometres and will expire on April 15 2048.

The road to Kabundji village: Because it is sandy and overgrown, farmers light fires to help keep it clear. Photo: Jonas Kiriko

The first health institution under construction in the village of Kabundji, built by the state with mining royalties. Photo: Jonas Kiriko

On the ground

According to testimonies collected on the ground in and around Kengere, outsiders are now taking control of negotiations with the company. The communities who used to live in the village simply have to accept the deals after the fact.

The Congolese Mining Code of 2002, as amended in 2018, makes consultation with local communities mandatory when a mining concession moves from exploration to an exploitation or operating permit. Neighbouring communities must also be consulted before any renewal or extension of exploitation permits.

“We were recently informed that a mining company had obtained an exploitation permit in our village. This means that many of us will find ourselves unemployed,” said Moïse Mwana Bute, a resident of Mushima village.

He not only fears losing the right to access his land, but that the mining company will not hire local labour because they are often perceived as underqualified.

“My brother and other villagers grow corn in the area. They too could lose their land. And since we were not consulted, we do not know if they will be able to obtain compensation. We are not opposed to companies coming to set up in our area, but we need to be informed,” Mwana Bute said.

“Recently a mining company built a hospital, which was a prerequisite for its mining licence, but we do not know when this was decided. If we had been consulted, we might have [highlighted] other priorities – mainly the road or the cellular network, for example,” said Medark Kyungu, who lives in the village of Kabundji.

To access his village, one must either ride a motorcycle or a bicycle, or walk. The track is sandy and often overgrown, since it crosses a vast savannah area. Farmers light wildfires sometimes to clear new paths to reach the various villages south of Kolwezi.

Esperant Mwisha Mali, a researcher at the University of Lubumbashi and specialist in the governance of the mining sector, said it is the responsibility of the company holding a permit to inform local communities.

“If there is relocation or environmental impact, the first victim will be the community. For this reason, [local communities] must be informed of the existence of a permit and the events that follow its issuance,” he said during a seminar on the ethical sourcing of cobalt in the DRC, held in June 2024 by the African Great Lakes Centre at the University of Antwerp in Belgium.

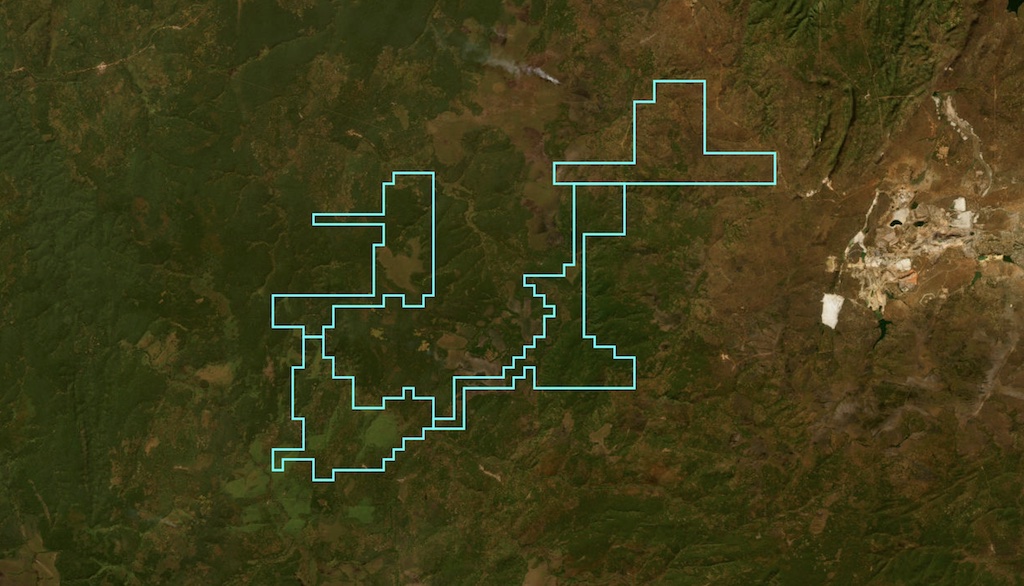

The two Ivanhoe subsidiaries have exploitation permits for copper mining in the southeast of the country. Map: C4ADS. Source: Spatial Dimension’s DRC Cadastre Minier (data as of Aug 1, 2024)

Satellite image of a village within Kengere Mining’s permit. Source: Google Earth, August 13 2020

Makoko SA was granted four connecting exploitation permits for copper that cover an area of 424 square kilometres. Graphic: C4ADS. Source: Spatial Dimension’s DRC Cadastre Minier (data as of Aug 1, 2024)

Cobalt supply

According to the university, approximately 60% to 70% of the world’s cobalt supply currently comes from the southeastern provinces of the DRC where these villages are based. Other transition minerals used in “green energy” production, including copper and lithium, also come from this part of the country.

“While the majority of the DRC’s cobalt is produced by large-scale industrial mining, an estimated 20% comes from rudimentary small-scale mining. Alongside growing demand, increased attention is being paid to human rights abuses occurring upstream of the cobalt supply chain, with particular attention to child labour and appalling working conditions in the cobalt industry, ” states an African Great Lakes Centre report.

In order to position the DRC in the global value chain of batteries, clean energy and electric vehicles, the Congolese government created the Congolese Battery Council in December 2022. This is a public body created with the sole aim of setting up, promoting and managing a value chain of minerals used in the manufacture of batteries.

The DRC has significant reserves of lithium, which is an essential component of batteries. Implemented in partnership with Zambia as part of a joint project to develop lithium reserves, the Congolese Ministry of Industry says it needs US$30-billion to develop this electric battery project.

The only manual well in the village of Kabundji and its surroundings, serving about 10,000 inhabitants. Photo: Jonas Kiriko

Mining code

Demeester Maloba, a Congolese journalist specialising in mining and environmental issues, said according to article 80 of the current Mining Code, consultations on mining operations must be carried out beforehand with local communities, including on the possible conversion of a permit from exploration to exploitation.

“The community must be at the centre of the process,” he said. The code stipulates that “the operating permit is renewable provided that its holder undertakes in writing to respect the conditions, which define social responsibility towards the local communities impacted by the project activities…,” he added.

Esperant Mali said the dialogue mechanism involving local communities and mining companies must be strengthened: “When a company gets a licence to operate, part of their role is to connect with the community members who live on the land for which the licence was issued.”

“This work must be done in collaboration with CAMI [the mining registry under the supervision of the mininster of mines] and with civil society organisations, which should inform the communities that the space they live in has been granted to a company and tell them what they will receive in return,” he recommended.

Efforts by Oxpeckers to find out from CAMI whether the non-involvement of community members in mining permit processes could lead to the permits being revoked were unsuccessful. Several email exchanges took place with the communications department of this public company in charge of regulating permits before the communications were blocked without any explanation.

Trucks at the Kasumbalesa crossing, the main exit point on the border with Zambia. DRC exports most of its minerals in raw form. Photo: Jonas Kiriko

Political connections

Ivanhoe Mines, based in Vancouver, already exploits copper in the Kamoa-Kakula mine more than 20km southwest of Kolwezi, capital of the province of Lualaba. This copper mine is a joint venture between Ivanhoe Mines (39.6%), the Chinese company Zijin Mining Group (39.6%), the DRC government (20%), and Crystal River Global Ltd registered in the British Virgin Islands with its headquarters in Hong Kong (0.8 %).

Zijin Mining was involved in forced evictions of the population around Kolwezi in 2022 as part of the expansion of its copper and cobalt mines, according to an Amnesty International report. This Chinese company has also been singled out for the use of mineral products with high radiation levels as part of its Commus project in Kolwezi, earning it a temporary suspension by the Congolese government in April 2024.

In an article published on April 19, Africa Intelligence revealed that Zijin Mining was involved in the Manono lithium project in the province of Tanganyika in southeastern DRC and would have paid a sum of US$70-million to “an obscure Congolese NGO” whose leaders had links to the ruling Union for Democracy and Social Progress party.

Oxpeckers has not been able to establish whether Ivanhoe and Zijin Mining are cooperating on the Kengere mining projects. Data indicates that Ivanhoe’s subsidiary Makoko SA is 10% owned by a Congolese citizen reputed to be close to the family of the former president of the DRC.

Emails sent to Ivanhoe inquiring about it links with Zijin Mining, in particular its participation in the Kengere Mining and Makoko SA projects, remained unanswered at the time of publication. Both companies are registered in Lubumbashi, but neither has an online presence and could not be found in available trade data.

Oxpeckers also wanted to find out if Ivanhoe and its subsidiaries plan to meet the disgruntled communities in Kengere in order to discuss their expectations.

Consultation with local communities during all stages of the process helps companies to protect their investments and also to comply with regulatory texts in the mining sector, commented Florent Musha, a member of the civil society and urban coordination organisation of Kolwezi.

Jonas Kiriko is an investigative journalist based in the DRC specialising in topics related to environment, agriculture and water. This investigation is part of the Oxpeckers #PowerTracker series titled ‘The human cost of energy in Africa’, and was produced in collaboration with the Center for Advanced Defense Studies (C4ADS).

Find more Oxpeckers investigations into transition minerals here