12 Jul Dark side to ‘a new dawn’

Tanzania is banking on its natural resources during the global transition to clean energy, but analysts warn there are dangers ahead. Oscar Nkala investigates

Energy demand: Tanzania’s transition minerals include an estimated 70-million tonnes of graphite ore (above), commonly used in electrodes for batteries and fuel cells. Photo supplied

East Africa’s Tanzania is one of several African countries predicting “a new dawn” for its mining industry as industrialised nations race to secure critical transition minerals to power the switch from fossil fuels to clean energy options.

It is estimated the sector will reach $6.6-billion in value in Tanzania by 2027, according to recent market analysis by the United States International Trade Administration.

“In Tanzania, [there’s] a new dawn that’s ready to fuel the global energy transition… the demand for rare earth elements and critical minerals is ever-increasing. Working to meet this demand, mineral exploration in several parts of Tanzania has increased substantially in recent years,” the organisation stated.

The country’s natural resources include gold, copper, silver, nickel, lead, cobalt, graphite, manganese, uranium and 24 rare earth elements. It is also the only source of tanzanite gemstones, found in the foothills of Mount Kilimanjaro.

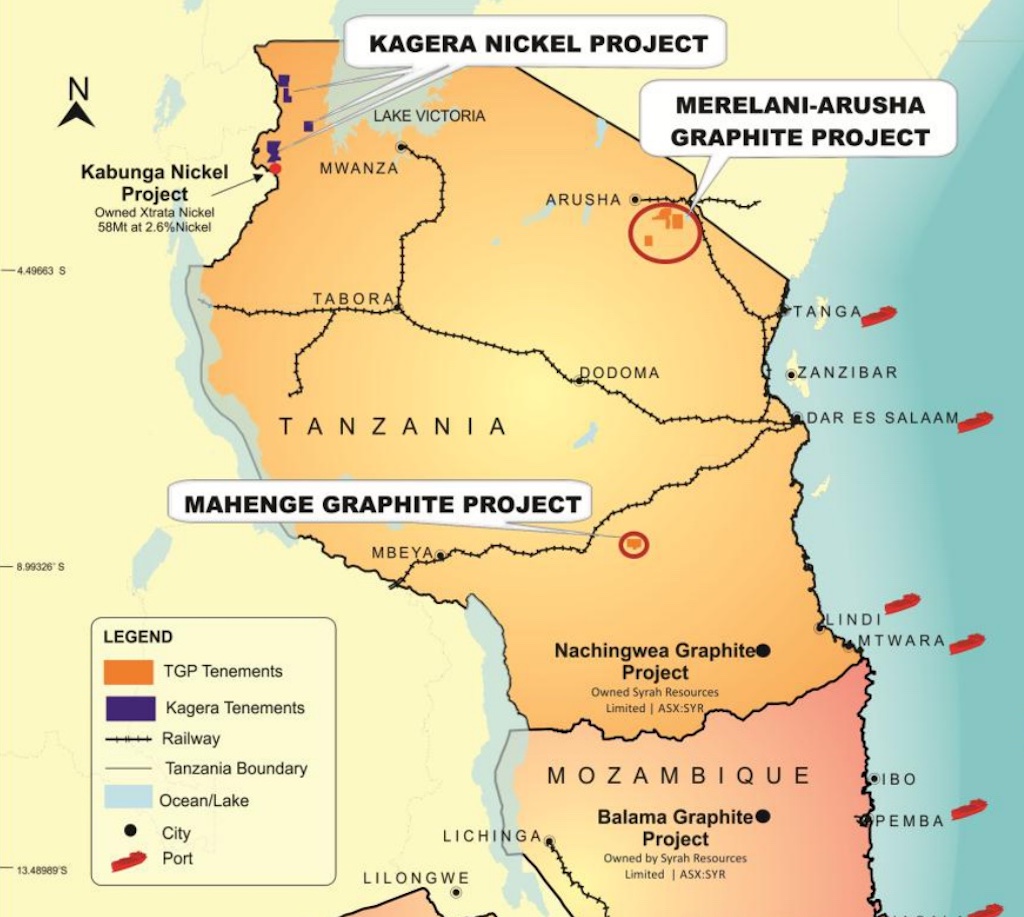

Its transition minerals include an estimated 70-million tonnes of graphite, commonly used in electrodes for batteries and fuel cells, in supercapacitors for energy storage, in nuclear reactors and solar panels. At least 1.52-million tonnes of nickel ore have been confirmed in ongoing exploration works in the Kagera region in the north-west. Though no quantity estimates have been given yet for lithium, it occurs in abundance.

Most of the new mining projects are still at exploration and development stage, but mining policy analysts have already warned of the dangers ahead.

“While critical minerals offer opportunities, there are risks for producers like Tanzania,” said Moses Kulaba of the Governance Analysis Centre at the Natural Resources and Governance Institute based in Dar es Salaam. “These include policy gaps, supply chain governance risks, the geopolitics of consumer nations as well as investment and revenue management risks.”

Rare gems: Tanzania is the only source of tanzanite gemstones, found in the foothills of Mount Kilimanjaro. Photo supplied

Dark side

A research paper published by the African Climate Foundation in 2023 warned the Tanzanian government to amend existing mining regulations in order to capitalise on critical transition minerals investments.

“While critical minerals developments have not delivered transformation yet in Africa, the dark side of the energy transition has become visible with the pollution of soils, air, water contamination, toxic residuals, intensive consumption of water and power, workplace and environmental risks, child labour, sexual abuse, corruption and armed conflict in the mining areas. These problems are doomed to become unsustainable given the increasing pressure on critical minerals extraction from major industrialised economies,” it states.

An assessment by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) of the opportunities and risks that come with critical minerals exploitation in Tanzania and other African countries highlights the high environmental, social, economic, geopolitical costs for producer countries: “While the growth of mineral supply value chains plays a vital role in the clean energy transition, the production and processing of these minerals can lead to a myriad of negative consequences.

“These include significant greenhouse gas emissions from energy-intensive mining and processing activities, environmental impacts such as biodiversity loss and pollution as well as social impacts including human rights abuses, child labour and negatively impacting on indigenous people’s rights.”

Investors in Tanzania’s new mining sector also face challenges arising from multiple laws governing the mining business, UNEP added. Among other remedies, Tanzania should streamline the issuing of mining permits, ensure regulatory clarity and promote transparent governance in the critical minerals sector.

New era: Most of the transition mining projects are based in the north-west of the country, and are still at exploration and development stage. Photo supplied

Geopolitical issue

Critical transition minerals investments have become a geopolitical issue, with the United States attempting to counter Chinese dominance of the sector. US companies have taken the lead in investing in lithium prospecting, and the biggest lithium concessions holders in Tanzania are US companies Titan Lithium and C-Growth.

Tom Sheehy, a research fellow at the United States Institute of Peace, said the US expects Africa to provide some of the 50 critical minerals needed to support technological innovations in the US.

“Critical minerals development in Africa impacts the US at the level of peace and security. Much of the world is coming to Africa in search of critical minerals, but the question is: will these minerals be developed in a way that contributes to African economic development and promote social stability? Or, as we have often seen, will these resources be developed in a destructive and exploitative way?” he said.

“We want to encourage critical mining partnerships that are mutually beneficial with African countries. This means ensuring that critical minerals do not fuel conflict.”

Sheehy said the US will continue to invest in Africa’s critical minerals sector in a responsible way. “Transparency and the rule of law will be critical for African countries to attract investments. They must honour investment rules by adhering to contracts and resisting arbitrary rulings.

“The US and its Western partners will respond to investment opportunities in Africa, but only if there is sufficient confidence in the business climate. If not, there are many competing investment destinations to check globally,” he said.

Mines and Minerals Minister Anthony Mavunde: ‘Tanzania is re-defining the script.’ Photo supplied

Government strategy

Tanzania’s Mines and Minerals Minister Anthony Mavunde said the government is crafting a strategy to guide investments in the critical minerals sector. The government has plans to expand the mining industry to ensure that all Tanzanians benefit, he added.

“Starting in July 2024, we will conduct an in-depth geological survey in two blocks with a total area of 163,574 square kilometres. This will lead to the establishment of several more mines, and significantly open up new investment opportunities across the mining sector,” Mavunde said.

The government is also promoting new nickel, lithium and graphite refineries in-country to promote value addition and create more jobs down the mineral value chain. A new strategy to regulate artisanal mining will be unveiled as part of broad measures to improve working conditions for artisanal and small-scale miners, Mavunde said.

The government is working on a critical minerals policy that will ensure reliable supplies, stimulate further exploration and foster mining innovation while championing the adoption of sustainable and responsible mining practices, he said.

“Tanzania is re-defining the script, not with empty promises but with ground-breaking action which offers transformative partnerships. Our vision is not to just dig up the minerals, we want to ignite the engines of prosperity.”

He said the government is enacting new laws to protect artisanal and small-scale miners from being prejudiced by big mining companies in disputes over mining licences. The regulations are meant to address frequent conflicts arising from mining licence ownership disputes as big mining companies are accused of abusing agreements made with their small-scale counterparts.

The government is also working hard to prevent illegal mining and disrupt the operations of several transnational theft and smuggling syndicates which have established themselves in mining sites in the Lake Victoria basin, he added.

A tailings dump at North Mara Gold Mine: Conflicts erupted over expansion into community lands early in the 1990s. Photo © RAID

North Mara

Analysts warned that mining for transition minerals needs to avoid the long-running problems associated with the North Mara Gold Mine in north-western Tanzania, which is surrounded by five poverty-stricken villages situated on land ravaged by opencast artisanal mining.

In operation since 1930, the North Mara mine has changed ownership many times, the most recent being its acquisition in September 2019 by Canadian company Barrick Gold Corporation, part of the London Stock Exchange-listed Acacia Mining. The mine is now operated by Twiga Minerals, a joint venture in which Barrick Gold controls 84% and the Tanzanian government controls 16% free carried shares.

Gold is not the only mineral attracting investor and artisanal miner interest to the North Mara region. Its mineral resources include copper, cobalt, silver, chalcopyrite, pyrite, quartz and various chlorite group gemstones.

Human rights and social justice issues have been haunting the North Mara and Bulyanhulu mine, also owned by Barrick, since conflicts erupted over expansion into community lands early in the 1990s.

Most residents in the surrounding villages are resentful of the North Mara mine, stemming from what they view as their forceful eviction from their lands and artisanal gold mining sites to accommodate the mine’s expansion between December 2019 and September 2023. Those who spoke to Oxpeckers in Kewanja village said animosity towards the mine is exacerbated by abuse committed by police stationed at the mine and by government officials.

“The problems revolve around the bad relationship between the mine and the communities. There is no trust. Instead, there is mutual suspicion and deep-seated resentment which creates a typical ‘us and them’ relationship,” said Joshua Matombo, a resident of Kewanja village.

“We see the North Mara mine as a profit-driven actor who turned our lives upside down with the help of the government, which collects the taxes. The mine treats us like aliens on our own land. They call us trespassers and illegal miners, which is an insult because we inherited these gold mines from our forefathers.”

In response to concerns about these issues recently raised by Human Rights Watch and the United Nations Human Rights Commission, Barrick’s chief executive officer Mark Bristow said allegations of mine complicity in police brutality, use of the Tanzanian police as a private militia and human rights abuses linked to the evictions were baseless. The company has requested the government and Tanzanian Human Rights Commission to investigate the allegations, he said.

Regulatory challenge: Artisanal miners at work in Geita. Photo courtesy National Environmental Management Commission

Artisanal mining

Artisanal mining for both critical and non-critical minerals poses headaches for mining companies and regulatory challenges for the government.

In the north-western regions of Geita, Shinyanga and Kigoma, artisanal miners produce gold, copper, silver and quartzite gems. Local residents lament the environmental impacts of these mining activities, which include air and dust pollution as well as the discharge of toxic fumes and chemical residues into the atmosphere.

“In Geita, deforestation, mercury and cyanide pollution, dust pollution, noise pollution and chemical contamination of soils are the main problems caused by mining,” said a health technician who requested anonymity because they are not authorised to speak to the media.

Alpha Nyatomba is the director of Population and Development Initiatives, a non-governmental organisation that aims to promote land and environmental rights in communities affected by the mining in north-western Tanzania. He said communities living in mining areas face problems of water scarcity, deforestation and chemical contamination of water sources.

The gold mining and processing factories around Geita dump at least 27kg of mercury a year into the local rivers and environment, according to a study conducted by the National Environmental Management Commission, a government body established to undertake environmental enforcement and awareness raising in Tanzania.

The study found at least five major mines in the area emit between 7kg and 14kg of toxic atmospheric gases annually from amalgamation burning of gold and other mineral purification processes.

At least 17% of the Geita Forest Reserve was destroyed annually to make way for mining between 2016 and 2020, the study found. The forest clearance process included the destruction of vital habitats and the disruption of natural ecosystems key to the mitigation of climate change impacts.

Environmental impacts: Artisanal mining in areas such as Shinyanga (above) causes water pollution, deforestation and land degradation. Photo: Oscar Nkala

Chemical pollution

Recent assessments of chemical pollution linked to artisanal and small-scale mining in the nearby Chunya District showed its rivers contained 10 times more mercury than the safe limits prescribed by the World Health Organisation. A 2020 study into the public health impacts of mining in Metau District recorded a 20% increase in respiratory illnesses that were directly linked to air pollution from mining activities.

The most widespread environmental impacts of mining in north-western Tanzania include water pollution, deforestation and land degradation. The study said a lot of work remains to be done to reform, harmonise and enforce Tanzania’s fractured legal and policy frameworks guiding the operation and regulation of the sector.

“At least 10 different state institutions are involved in oversight and together visit 94% of the artisanal mining and processing sites in north-western Tanzania. They perform various inspections on safety, environment and health, collect taxes, royalties and fees, provide training and assistance, collect data, take care of security and law enforcement and mediate conflicts.

“Yet cooperation and information exchange among these state actors remain ad hoc, as there exists no central coordination. Consequently, many sites are visited occasionally for one function or without knowledge of prior practices or inspections,” says the report.

“Structuring and systematising this coordination with a clarified division of responsibilities and channels of communication could increase the frequency, efficiency and impact of oversight functions.”

Oscar Nkala is a Zimbabwe-based Oxpeckers Associate who works on transnational investigations across borders in sub-Saharan Africa. This investigation is part of the Oxpeckers #PowerTracker series titled ‘The human cost of energy in Africa’.

Find the #PowerTracker tool and more investigations here