16 Nov Question marks over Namibia’s green hydrogen plans

Hyphen’s ambitious GH2 venture is flawed and opaque, according to local critics. John Grobler spoke to them

Lüderitz on the southwestern coast is where Hyphen is planning the largest green hydrogen project. Photo: John Grobler

Two years ago, Namibian President Hage Geingob caught locals by surprise at the COP26 climate change conference in Glasgow when his government appointed Hyphen Hydrogen Energy on a 40-year contract to set up one of the most ambitious green hydrogen projects in Africa.

Namibia is planning a series of million-dollar investments to become a major green hydrogen supplier to Europe and Japan as early as 2028. Both the European Union and the Japanese government have supported the venture, in the hopes of getting new imports to meet their climate change goals.

Hyphen is a Namibian-registered green hydrogen development company, specifically formed to develop such projects for international, regional and domestic supply. Green hydrogen (GH2) is produced through the application of renewable electricity, and offers an alternative to fossil fuels.

“We were a little surprised at the government’s choice of a partner,” said Phil Balhao, an opposition party member of the Lüderitz Town Council, the site where Hyphen’s project will be developed. He added other bidders with an “established track record”, such as South Africa’s Sasol and Australian Fortescue Future Industries, sent offers that “seemingly just got ignored”.

The envisaged Lüderitz complex would include the construction of a new deepwater port, a 6GW wind and solar farm, a mega desalination plant and a conversion plant capable of transforming hydrogen into 300,000 tons of ammonia fertiliser a year. Photo: John Grobler

Big ambitions

With a GDP of around $12-billion in 2022, Namibia’s plans on green hydrogen are big, aiming for more than $20-billion in investments. Government authorities are negotiating funding options with the EU, which plans to import around 10-million tons of hydrogen and ammonia by 2030.

“Today we have more than five such [green hydrogen] projects under development,” Geingob told the UN General Assembly on September 20 this year.

The largest of those five projects is Hyphen’s GH2 complex located on the country’s southwestern coast, near Lüderitz. This would include an initial 5GW wind and solar farm, a mega desalination plant that turns sea water to fresh water, a conversion plant capable of transforming hydrogen into 300,000 tons of ammonia fertiliser a year, and the construction of a new deepwater port to accommodate tankers to ship the end product around the world.

Hyphen says the project will require an investment of $10-billion, an amount almost equivalent to Namibia’s GDP. Hyphen also says the Namibian government is planning to buy a 24% equity stake in the company.

Through an information request, the EIB told Climate Home News that the funding has not yet been approved and is subject to due diligence.

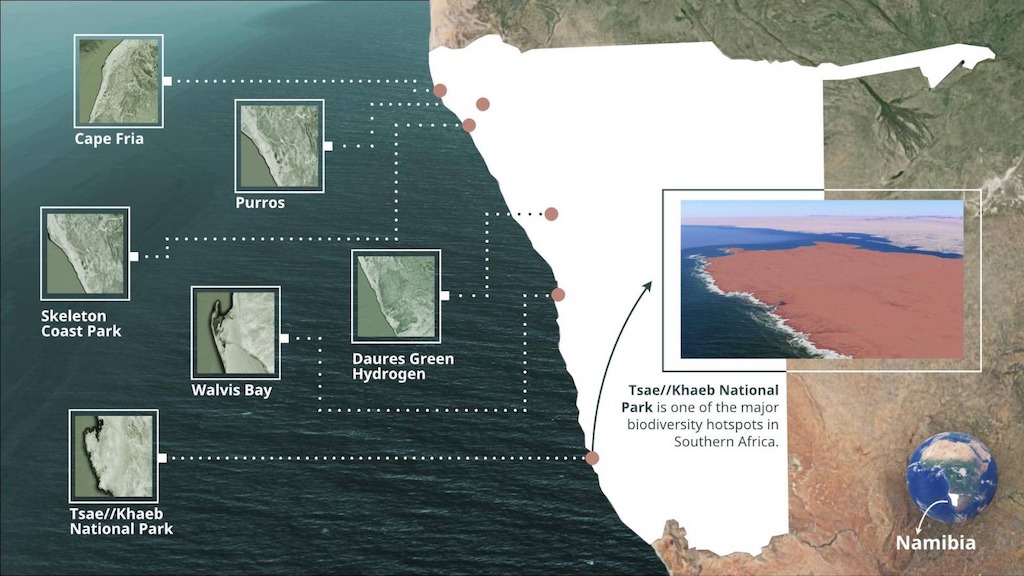

The sheer size of the Hyphen project at Lüderitz drove the planners to select the surrounding Tsae//Khaeb National Park, one of the major biodiversity hotspots in Southern Africa, as the construction site. Graphic: Fanis Kollias/Spoovio

Lüderitz project

Green hydrogen was dropped from Namibia’s official National Energy Policy in 2016 – only for it to re-emerge five years later as the central feature of Geingob’s Harambee Prosperity Plan II, said independent Namibian scientific and technical management consultant Detlof von Oetzen.

“Hydrogen was considered very promising, but it […] was based on still experimental technology like fuel cells that were still too expensive to use on a large scale,”

The sheer size of the Hyphen project at Lüderitz, covering an estimated 1,500 – 2,000km2, drove the planners to select the surrounding Tsae//Khaeb National Park, one of the major biodiversity hotspots in Southern Africa, as the construction site.

Hyphen’s plans not only require building a whole new N$40-billion (US$2.1-billion) port at Angra Point, 30km out on the peninsula across the Lüderitz Bay, but also call for the construction of a whole new town 15km inland to host what Hyphen says will be a 15,000-strong workforce that will double the current Lüderitz population.

Daures: Remote range area of Namibia’s endangered desert elephant and southwestern black rhino populations. Photo: John Grobler

Daures project

The next-biggest project of the five concessions allocated so far is the Daures Green Hydrogen project located halfway between the Brandberg massif and the Skeleton Coast some 600km north of Lüderitz. This project faces even bigger infrastructure challenges.

Not only is it located about 250km from the nearest port at Walvis Bay, but access to water, electricity or communication infrastructure in this arid and remote area on the edge of the Dorob National Park is limited.

Daures is also located within the range area of Namibia’s endangered desert elephant and southwestern black rhino populations, Von Oetzen pointed out.

Angra Point, site of a future Hyphen plant. Photo: John Grobler

Skills shortages

Despite the high ambitions, the Namibian government and Hyphen could find a shortage of skilled manpower and construction capacity, experts said.

“We do not even have a category for petrochemical or petroleum engineers at the moment,” said Sophia Tekie, chairperson of the Engineering Council of Namibia (ECN). “If we have any, they are registered as [one of 40] chemical engineers.”

“Although the ECN has 2,015 registered engineers in eight disciplines at present, about 30% to 40% of them are already retired and only do part-time consultancy work,” said her predecessor, Markus von Jeney.

Local construction capacity is also constrained, according to Bärbel Kircher, director of the Construction Industry Federation, where membership has declined from 480 companies in 2015 to 240 member companies, operating at only 50% capacity.

“Currently our local contractors are largely displaced by foreign contractors, excluding them from opportunities. This is often due to conditions set by external financiers,” said Kircher.

Namibian construction companies are not likely to benefit from the green hydrogen projects, Kirchner said. “The current procurement methods and trends do not provide a promising outlook for the future.”

Hyphen responded that it is still in an early stage of the project, but has developed a socio-economic development framework with the government that is being shared with the public via an ongoing roadshow.

“It is estimated that the project will create up to 15,000 new jobs during the construction phase, 3,000 permanent jobs during its operation, with the target for 90% of these jobs to be filled by Namibians and 20% by youth,” the company said.

James Mnyupe: The official ‘Green Hydrogen Commissioner’ . Photo: Facebook

Industry regulations

The GH2 plans are taking place under a lack of industry regulations and with little transparency, especially when allocating concessions, critics said.

All pre-independence legislation on the commercial trade of industrial gases, including Liquid Petroleum Gas (LPG), was repealed by the 1992 Petroleum Products Act. This left a regulatory vacuum around new technologies like green hydrogen.

This legal omission has enabled the Namibia Investments Development & Promotions Board (NIPDB), created in the Office of the President in early 2021, to seize control of the green hydrogen initiative that would otherwise fall under the remit of the Ministry of Mines and Energy, the critics said.

The NIPDB first issued the request for proposals for Hyphen’s project in 2021. A few months before, in September 2020, the board appointed James Mnyupe as the official “Green Hydrogen Commissioner” without a public recruitment process.

Previously a technical advisor to the Office of the President, Mnyupe had also been acting as an investment advisor to Bank Windhoek until July 31, its spokesperson confirmed.

In a televised speech, Mnyupe said the request for proposals was under the Ministry of Environment and was exempted from the Public Procurement Act, “where the underlying regulations that could govern concessions for example are absent or being drafted”.

“The Policy on Tourism and Wildlife Concessions on State Land affirms this,” he said. The NIPDB used this as a legal basis to propose the energy project within a national park and hold a closed selection process.

He quoted the policy by saying that “the tender board has concurred that the ministry is not required to follow the tender board procedures when tendering concessions under its jurisdiction. It is of the opinion that the authority to issue concessions in such areas rests with the minister.”

By law, the ministry must ensure that the awarding of concessions is competitive, fair and transparent and ensure that safeguards against favouritism, improper practices, fraud, theft and corruption are in place and followed.

The Nature Conservation Amendment Act under Section 17(2)(k) empowers the minister of environment and tourism “to establish a renewable electricity source for the purposes of the management of game parks, nature reserves and other protected areas or protection of the environment or the combating of climate change”.

Mnyupe said the bidding request for proposals launched in August 2021 met the spirit of both the Nature Conservation Amendment Act and the Policy on Tourism and Wildlife Concessions on State Land. “The request for proposals was floated live on various local and international media. The results were announced publicly on local and global media,” he added.

The Namibian government published a list of six bidders, who submitted nine bids between them. However, the content of the bids was not made public, nor the reasoning for Hyphen’s selection.

In response to questions, Mnyupe said the tender process was “conducted with the utmost transparency and fairness”. The three-person bid evaluation committee did a “detailed and comprehensive evaluation” of the proposals, supported by independent experts from the US government’s national renewable energy laboratory and the EU’s technical assistance facility on sustainable energy, he said.

Walvis Bay: Located about 250km away from the Daures project, second-biggest of the five concessions allocated so far. Photo: John Grobler

Transparency concerns

Civil society contested the bidding process, saying Hyphen’s selection was “concerning”. Under normal conditions, a project of this level would require increased transparency, including the reasoning for selecting Hyphen’s proposal, said Graham Hopwood, executive director of the Namibian think-tank Institute for Public Policy Research.

“That was never done because they used an obscure part of a conservation law because the project will take place in a national park,” said Hopwood.

The project could pose an economic risk to the country, Hopwood added, referring to Namibia’s stake in the company. “Why should we invest Namibia’s money in a project whose feasibility has not been established?” he asked.

Hyphen responded that the government had run a competitive tender process for the first land allocations, and the evaluation of bids was undertaken by independent experts. “The process, which closed on September 16 2021, was open to all bidders with six individual bidders submitting nine separate bids across the two land parcels,” the company said.

It was unreasonable to expect Hyphen to make public the feasibility and implementation agreement concluded between it and the government, a spokesperson responded.

“It is important to understand that the green hydrogen industry is intensely competitive, with billions of dollars in funding being mobilised and countries competing against each other to be first to market and attract investment.

“In a competitive world it would be irresponsible and to the detriment to the development of the Hyphen project and Namibia’s broader green hydrogen industry for it to publish commercially sensitive agreements in the public domain that competitor projects / countries could use to compete against Namibia,” Hyphen said in a statement.

John Grobler is an associate editor at Oxpeckers Investigative Environmental Journalism. This is the first of a series titled Shades of Green Hydrogen, a collaboration with Climate Home News supported by Journalismfund Europe’s Investigation Grants for Environmental Journalism

John Grobler is an associate editor at Oxpeckers Investigative Environmental Journalism. This is the first of a series titled Shades of Green Hydrogen, a collaboration with Climate Home News supported by Journalismfund Europe’s Investigation Grants for Environmental Journalism