18 Nov South Africa’s energy transition rises in the east

Mpumalanga, the province ‘where the sun rises’, takes centre stage in SA’s Just Energy Transition Plan. Yolandi Groenewald unpicks the details

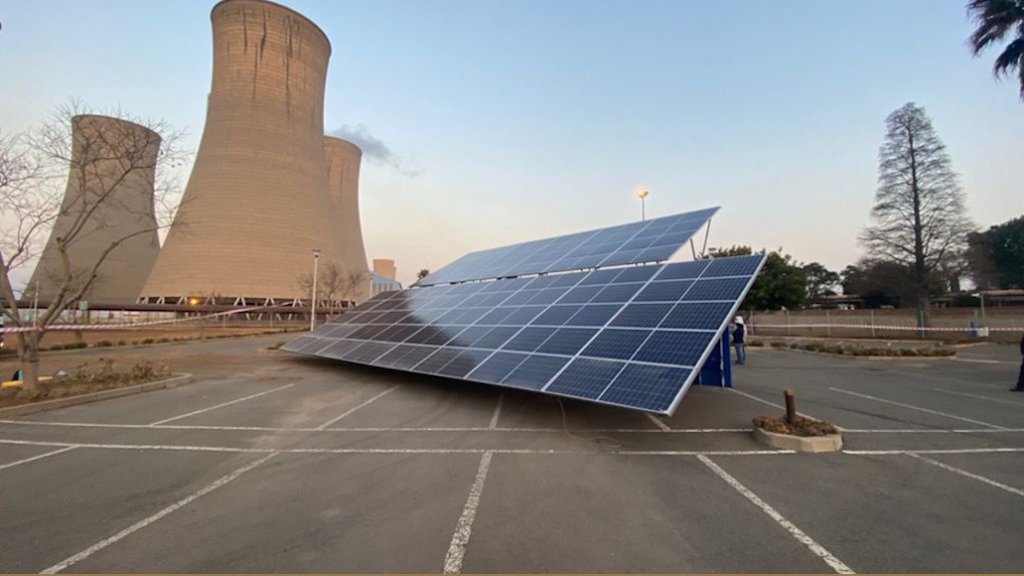

Out with the old, in with the new: Komati is being used to demonstrate how old power plants can be repurposed. Photo supplied

Mpumalanga province, historically the heartland of South Africa’s coal-fired power industry, will need R60,4-billion to move to a greener tomorrow, according to the country’s presidency. With its abundance of coal mines and ageing coal power plants, the province faces an uncertain future as coal is frozen out of South Africa’s clean future.

The architects of the country’s new energy deal posit an alternative economic diversification strategy that will include not only renewable energy opportunities but support for jobs in tourism, agriculture and mine rehabilitation in the province in the east, which borders Swaziland and Mozambique.

The transition will change Mpumalanga’s economy forever, according to the new deal, called the Just Energy Transition Plan (JETP). “The provincial economy is heavily dependent on coal for employment, the municipal rates base and community development activities,” the plan states.

Four priority investment areas for Mpumalanga are set out in the JETP and the investment plan released by the presidency on the eve of the United Nations COP27 climate change conference in Egypt, held from November 6 to 18 2022: firstly, to repurpose coal power plants and coal mining lands; secondly, to build economic diversification; thirdly, to assist with the transition of workers and communities; and lastly, to build enabling conditions for the transition.

Future power: The Just Energy Transition Plan aims to contribute to building economic resilience in Mpumalanga communities, as well as restoration of the environment. Photo supplied

The Komati model

The repurposing of old power stations is already on the go. Komati, one of Mpumalanga’s oldest power stations, was decommissioned in October in what is seen as a model for repurposing.

Situated halfway between the towns of Middelburg and Bethal, Komati had been in operation since 1961 and was a minor power station in state utility Eskom’s fleet, only generating about 1GW of power.

Mandy Rambharos, former general manager for Just Energy Transition at Eskom who has been closely involved in defining the JETP deal, said the power utility was learning by doing. Komati was the first step in this learning process.

She explained that Komati was being used to demonstrate how old power plants can be repurposed. Next in line according to Eskom’s plan are the Camden and Hendrina plants, due to close between 2023 and 2025.

Shortly before the release by President Cyril Ramaphosa of the investment plan (known as the JET-IP), the World Bank approved a loan of US$497-million (about R9-billion) to fund the decommissioning and repowering of Komati using renewables and batteries.

Eskom plans to use the loan to install 150MW of solar power, with some panels placed directly on the old mining ash heaps, as well as 150MW of battery storage and 70MW of wind power. All 193 employees at Komati have been offered alternative Eskom jobs.

Coal heartland: Mpumalanga currently produces 83% of the country’s coal, and 12 of Eskom’s 15 coal-fired power plants are found in two of the province’s districts. Photo © Jeremy Glyn

More than just a coal heartland

Lebogang Mulaisi, a commissioner at the Presidential Climate Commission and head of policy at trade union Cosatu, explained at a COP27 side event that Mpumalanga has so much more potential than merely being the heart of South Africa’s coal sector. Mine rehabilitation, for example, can be a serious intervention, while agriculture should also play a significant role in the transition, she said.

“It is not just about moving workers from one sector to another, it must be about fair wages and creating better new opportunities. Listen to the people that will be affected,” Mulaisi said.

Mpumalanga currently produces 83% of the country’s coal, and 12 of Eskom’s 15 coal-fired power plants are found in two of the province’s districts. Around 85% of South Africa’s coal-mining jobs are situated in Mpumalanga.

The JET-IP acknowledges that Mpumalanga residents suffer negative environmental and economic impacts from the coal industry. This includes “air and water pollution and the coal mining-related destruction of high-value agricultural land. A just transition is an opportunity to address both current development challenges and impacts from a coal phase-down,” the document states.

It also says Mpumalanga has important advantages that could support the just transition, including an existing industrial base and experienced workforce, excellent wind and solar resources, and proximity to electricity load centres and transmission infrastructure.

In setting up the JETP deal climate commission officials consulted local communities in Mpumalanga, but found people feel deeply ambivalent about the green transition. They are acutely conscious of the destructiveness of a carbon-intensive economy, and the social consequences of jobs such as coal trucking. Yet they are deeply anxious about the change that is coming.

Daniel Mminele, head of the Presidential Climate Finance Task Team: ‘We are working on translating pledge into tangible manner.’ Photo courtesy SA government

Retiring an ageing fleet

By 2035 Eskom plans to shut down nine power stations, most of them in Mpumalanga, terminating 15GW of power and putting up to 55,000 jobs at risk. The JET plan states that South Africa’s ageing fleet of coal power plants – totalling 39GW and averaging a lifespan of 42 years – will be “retired over the next three decades, with 22GW due to be decommissioned by 2035”.

Many of these power stations are at the end of their life and Eskom will have to forge a new path for the power stations that makes use of existing infrastructure such as transmission lines.

“Coal fleet closure will directly impact about 90,000 coal workers in the mines and power plants of the poverty-stricken Mpumalanga province where the sector is concentrated, having dire consequences for the extended number of livelihoods supported by workers in the sector, both in Mpumalanga and elsewhere in the country,” the plan states. The entire value chain – from mining and electricity production to end-use sectors – employed almost 200,000 people in 2020.

The closures and coal phase-out means no new jobs are being created in the sector, and young workers will not be entering the coal-mining workforce.

“Between 4,500 and 7,500 new jobs will not materialise,” the plan states. “Older workers typically exit the sector before the official retirement age. Over the decade, almost 18,500 older workers will leave coal mining, and many will require social support.”

It estimates a further 3,000 to 9,000 additional job losses will be attributed to decreasing coal demand over the period 2020-2030, especially from 2025 onwards.

Daniel Mminele, head of the Presidential Climate Finance Task Team, is all too aware of the economic impact of the transition and believes no one should be left behind in the process, least of all the coal workers of Mpumalanga.

“While the JETP is a strong pledge, we are working on translating pledge into tangible manner, with terms and conditions favourable to our country that will not impact negatively on future generations of South Africa,” he said.

Mpumalanga reinvented

Reskilling workers in affected industries will be crucial. Economists at the International Renewable Energy Agency said in a recent report on renewable jobs that to truly move to a new green economy, jobs cannot merely be shifted to electricity generation once again. The researchers at South Africa’s JET-IP concur: new jobs need to be created in renewable manufacturing, and South Africa will need to invest in such an industry.

Thus, Eskom plans to train workers and open a factory on the Komati site to produce micro-grids, and mobile solar-power units are being built on old shipping containers. The ambition is to employ 500 full-time workers churning out 900 units a year.

Eskom is also encouraging solar and wind operators to set up shop in Mpumalanga – with its readily available transmission lines – by auctioning off spare land. The first round resulted in contracts for 2GW of power, according to Eskom.

Architects of the JET-IP believe its outcomes should contribute to building economic resilience in Mpumalanga communities, restoration of the environment, creation of better jobs, and contribute to ensuring human capacity and capabilities. But to achieve this transition will require major investments, sparked by funding already committed.

This is the deal: French President Emmanuel Macron (left) receives the JET-IP from President Ramaphosa while US Special Presidential Envoy on Climate Change, John Kerry, and EU head Ursula van der Leyden looks on at the Sharm El-Sheikh Climate Implementation Summit in Egypt. Photo courtesy US State Service

Real money

At COP26 held in Glasgow late last year, European donor governments pledged $8.5-billion towards South Africa’s transition. At this year’s COP27 the first real money started flowing to South Africa from the deal when the country secured loan agreements of €600-million (R10.7-billion) from France and Germany.

Funding from the $8.5-billion JETP deal is intended to be disbursed over the next five years. Just before COP27 Ramaphosa said about 2.7% of the funding would be in the form of grants, while the balance will be loans and concessional loans from various finance institutions, raising concerns about South Africa’s debt levels.

The president said $7.7-billion has been allocated to the electricity sector. Green hydrogen projects will receive $700-million and the electric vehicle sector $200-million.

But he pointed out this was just a drop in the ocean: South Africa’s electricity sector will need R648-billion over the coming five years for generation, storage and network infrastructure. This includes R242-billion for wind, R233-billion for solar, R132-billion for transmission, R23-billion for batteries, R14-billion for distribution and R4-billion for coal plant decommissioning, Ramaphosa said.

Yolandi Groenewald is an associate editor at Oxpeckers Investigative Environmental Journalism specialising in the business and politics of climate change. This investigation is part of the Oxpeckers #PowerTracker series interrogating financial flows to power generation projects in Mpumalanga