21 Oct Sweet and sour future for sugar power

Giant sugar companies in Eswatini diversified into biopower cogeneration to keep the lights on, but how long will the strategy last? Phathizwe Zulu investigates

A worker throws dry sugarcane waste, called bagasse, into a fire to generate electricity at a sugar mill. Photo © REUTRS/Jose Cabezas

Facing climate change challenges and ever-increasing demand for energy, Eswatini has relied on electricity cogeneration by biomass and hydropower. Almost 100% of the electricity generated in the Southern African country, formerly known as Swaziland, is from hydropower and sugarcane-based biomass cogeneration.

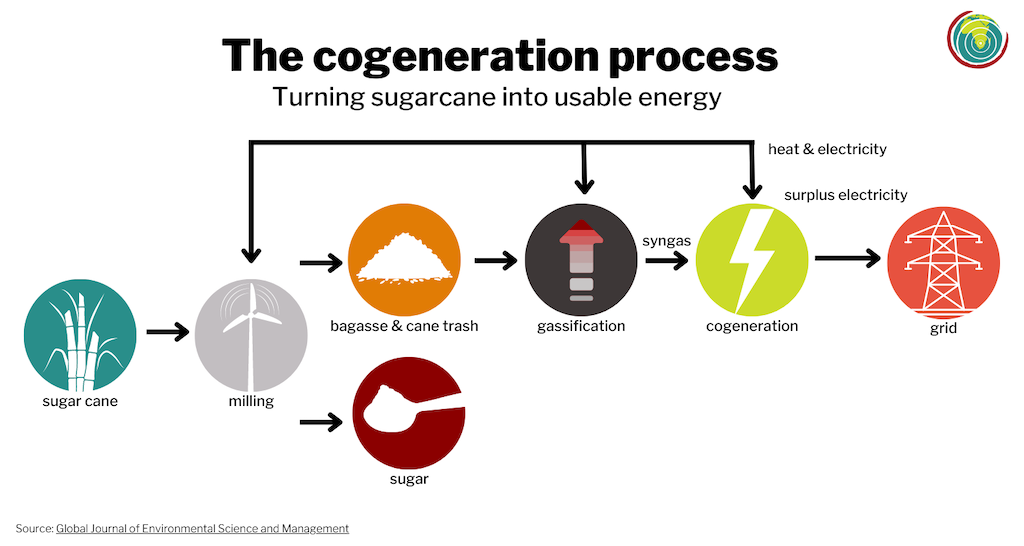

The by-product from the crushing of sugarcane, called bagasse, is recycled and used as boiler fuel in the sugar mills. It is burned at temperatures of up to 400-800ºC to produce steam, which is used as heat for the milling process and to drive turbines that generate electricity. This process is called cogeneration.

Sugar companies Ubombo and Simunye have invested billions of rands into biomass cogeneration projects and are supplying the national grid with excess power generated.

But in the face of such massive investments, what does the future hold for these cogeneration plants?

Renewable energy consultant Rex Brown said the mounting climate change challenges facing the sugarcane industry mean over-reliance on cogeneration energy production is a risky business because biomass is a short-term solution.

“It has inherent risks from climate change itself,” he said. “If investors are willing to invest millions in such energy plants, it is their risk. My advice would be to avoid such power plants. There is only one future: renewable energy based on solar and wind.”

Biopower

Ubombo Sugar Limited was the first independent power producer in Eswatini to supply biomass power to the national grid. On average it produces 165 gigawatt hours (GWh) of electricity annually, of which about 60GWh is supplied to the national grid under a commercial power supply agreement with the state-owned Eswatini Electricity Company (EEC).

Another sugar giant, the Royal Eswatini Sugar Corporation, developed the 47MW Simunye Sugar Cogeneration Plant in multiple phases over the years. It is producing power to support its own production processes and excess electricity is shared with residents of surrounding villages. At this stage it does not sell power to the national grid.

The country’s total installed generation capacity in 2014 was around 180MW, according to its Energy Master Plan 2034. Biomass made up 106MW, hydropower 61.5MW, diesel 9MW and local coal-fired power plants 2.2MW.

The EEC owns and operates four hydro-power plants that contribute 15% to 17% of the total energy consumed. Residual demand is met by power imported from Mozambique and South Africa (Eskom), according to an overview of the energy sector by USAID Power Africa.

A National Energy Policy adopted in 2018 was a game changer, driving rapid transformation of the electricity industry to boost private-sector investment.

Former Ubombo Sugar managing director Oswal Magwenzi said cogeneration was a diversification strategy aimed at avoiding putting all the company’s eggs in one basket.

“Ubombo Sugar created a revenue stream from cogeneration,” he said. “It is about not having one revenue stream coming from one source but coming from markets with different characteristics.

“How do we characterise the sugar market? Volatile sugar prices, changing consumer tastes, ever-changing market risks and ever-growing threats of climate change.

“On the other hand, how do we characterise the electricity market? Ever-increasing prices, a growing demand and government promoting renewable energy as an effort or attempt to fight climate change.”

Magwenzi said cogeneration tended to be a very good strategy for coping with “systematic weather risks”.

“The government is working hard to become self-sufficient while promoting renewable energy, and as a result it provided a growing market for our cogeneration project. It demonstrates that diversification has worked for Ubombo Sugar: now 65% of our profits come from sugar, 35% come from our cogeneration,” he said.

Ubombo Sugar Limited, located in the southeast of the country, was the first independent power producer in Eswatini to supply biomass power to the national grid. Photo © Ubombo Sugar Ltd

Sugar decline

However, the sugarcane industry is in decline, and Rex Brown predicted that post-2050 it may not exist due to various factors.

“We know how fast the climate is changing. We know how long it will take before that industry experiences tough economic hardships, it is an industry on a downswing,” he said.

Sugar’s contribution to the health crisis in the developed world has exacerbated the need to reduce sugar intake globally, he added.

The government has made a commitment that by 2030 half of its electricity will come from renewables, according to the Energy Master Plan and its nationally determined contributions under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change(UNFCCC).

Brown said all power in the country will need to come from renewables if it is to meet the global target of achieving net zero emissions by 2050.

“To meet the average power demand of 300MW, at least 100MW to 150 MW renewables has to be installed by 2030 and another 150MW by 2050,” he said.

Biomass is not strictly renewable and is not the cleanest of energies, Brown said, because volatile organic compounds are released during processing that contribute to global warming.

“But for a small country like Eswatini biomass does offer a little bit of hope and breathing space for more renewable sources of energy like solar and wind to take over eventually,” he said.

Mary Stewart, an international climate risk and energy transition expert, agreed that biomass has the potential to be a bridging technology to renewables while economies seek to reduce emissions. But it will be challenging to find a place for it in 2050, she said.

“If we are going to reach net zero by 2050, we need to invest in technologies which do not result in emissions at all. While the burning of biomass is considered ‘better’ than the burning of fossil fuels, it does still result in emissions,” Stewart said.

Rex Brown: ‘For a small country like Eswatini biomass does offer a little bit of hope and breathing space for more renewable sources of energy like solar and wind to take over eventually.’ Photo © Phathizwe Zulu

Carbon taxes

The process of using waste produce (bagasse) and wood chips to run cogeneration plants through combustion in order to release stored energy will in future subject Eswatini’s sugar companies to carbon taxes.

Brown noted that the European Union is one of the principal markets for Swazi sugar, and that in the near future electricity consumers and businesses would demand clean energy – a move that is expected to place further strain on the future prospects of biopower projects.

In a briefing in July this year, the EU Parliament announced that a new carbon border adjustment mechanism would require EU importers to purchase certificates equivalent to the weekly EU carbon price from 2026. It will initially apply to imports in five emissions-intensive sectors deemed at greater risk of carbon leakage: cement, iron and steel, aluminium, fertilisers, and electricity.

“This new carbon tax on imports means they will look at the carbon footprint of your product,” Brown said. “An assessment will be done on how much carbon energy went into sugarcane and when it arrives in Europe there will be tax on that. To avoid the tax, millers must get their energy from clean sources.”

Stewart said the new mechanism aims to levy the same carbon price on products produced outside the EU as is levied inside the EU.

“This extends to electricity,” she said. “At present it does not extend to sugar, though indications are that the mechanism will extend to cover other sectors in time. It is likely that it will extend to foodstuffs in five to 10 years at least, though it won’t be immediate.”

According to Ubombo Sugar, opportunities for renewable energy generation afforded by the sugar production process assist the company to minimise its carbon footprint.

“The company has a ready supply of renewable fuel: 96% of Ubombo Sugar’s energy consumption is provided from renewable sources – primarily bagasse, supplemented by wood and other biomass,” the company stated in its socio-economic impact assessment report of 2017.

Ubombo was responsible for only 9% of the total carbon emissions of its parent company, Illovo Group, the report added. To reduce emissions, the company had installed wet scrubber systems in boilers, and monitors transport emissions on a monthly basis.

Power trading

Eswatini is part of the Southern Africa Power Pool (SAPP), which offers a wide choice of energy markets in the region. SAPP trades electricity across borders, and opens opportunities for independent power producers.

“Producers are no longer limited to the national buyers – a producer in Eswatini can sell power to a consumer in Malawi, for instance. Because of the power pool, the country is open to a huge market demand within the region,” said Brown.

“We were informed recently that a new inter-connector that is joining Mozambique with Tanzania will link SAPP with the East African power pool. We’ll now have potential customers all the way up to Ethiopia, the energy trading market potential is huge,” he said.

Elisha Mutambudzi, trading officer at the SAPP Coordination Centre, said the power pool’s role is to manage electricity trading systems and markets across Southern Africa, helping to ensure SADC member states have access to affordable, secure and reliable energy. It acts as an intermediary between buyer and seller for every trade concluded on the auction market.

“It issues daily invoice contracts for each active trader and provides back office accounting feed to member utilities. SAPP guarantees that every buyer receives power and every seller gets paid. The market operator bears the foreign exchange risk and credit risk involved in every transaction,” he explained.

The market operator also provides a reliable electricity price index for the region, as well as trading/clearing services, scheduling, delivery, banking, risk management, record keeping and reporting, Mutambudzi said.

“Our aim is to pool the cheapest source of generation to meet demand,” he said. “Transparency offers more possibilities and higher security for institutional investors.

“The SAPP market enables a more efficient procurement or sale of electricity compared to bilateral contracts – there is less work involved in closing deals over the trading platform compared to bilateral trading,” he said.

A section of the production plant powered by Ubombo Sugar’s cogeneration programme. About 35% of the company’s profits come from cogeneration. Photo © Ubombo Sugar Ltd

Investment opportunity

SAPP chief engineer Alison Chikova said Eswatini had committed only 1% of its 59MW capacity to the pool. That leaves 99% of the identified capacity in Eswatini still available for investors.

In its 2020/21 annual report, the EEC indicated that trading in the markets had greatly improved because the COVID-19 pandemic led to surplus supply in the region – owing to stringent restrictions as most countries went into lockdown, resulting in some businesses suspending or reducing operations.

“As a result, total energy traded in the SAPP markets significantly increased from 32,856.7MWh recorded in the 2019/20 financial year to 201,973.3MWh. Even though the foreign exchange rate level continued to be a challenge, total savings from trading in the markets increased almost six-fold from R6.5-million to R37.8-million,” states the report.

The communications manager of the Eswatini Energy Regulatory Authority, Teclar Maphosa, said among the solutions to energy capacity challenges in the SADC region is the integration of the grid and ensuring an enabling regulatory environment to allow regional electricity trade.

“From a regulatory perspective, we have identified the surge in renewable energy solutions as a potential risk if not well managed and appropriately responded to. Consequently, the authority has made it a strategic imperative to actively identify emerging technologies and models in the electricity industry and develop the necessary capacity to respond to them,” said Maphosa.

“It is our belief that efforts to improve regional integration and trade will certainly encourage local investors to participate in the regional electricity market through SAPP,” she noted.

Questions and requests for interviews sent to Ubombo Sugar, the Royal Eswatini Sugar Corporation and the EEC were evaded. Eswatini Bank also refused to answer questions about the funding of renewable energy entrepreneurs.

Wonder Mkhonza: ‘Where workers lose their jobs, there must be a transfer of skills to help them to remain active in the economy.’ Photo © Phathizwe Zulu

Job protection

Wonder Mkhonza, general secretary of the Amalgamated Trade Union of Swaziland, expressed concern at the way the energy transition is being handled by the private sector.

“The transition is not as honest as it should be. No one is keen to take interest in ensuring that jobs are protected,” he said. “A just transition means jobs are protected.

“Where workers lose their jobs, there must be a transfer of skills to help them to remain active in the economy. But that is not the case. No one is coming out clearly to show what and how the transition should happen justly.

Mkhonza said electricity workers should become independent power producers, and the government should ensure that the workers are empowered.

Brown, however, is optimistic that the renewable energy sector is the solution to jobs scarcity in the country.

“There are a lot of jobs that will be created,” he said. “A number of people will be involved in the renewable energy market, either as developers, operators or as maintenance engineers.”

Brown noted that, unlike coal or biomass, clean energy will have a lot of potential for small industries: “We know sugar as the ‘Swazi gold’, but renewable electricity will be the ‘new Swazi gold’ in future.”

Phathizwe Zulu is a freelance journalist based in Eswatini. This investigation was completed with the support of the Oxpeckers Investigative Environmental Journalism #PowerTracker project and the Centre for Investigative Journalism’s Open Climate Reporting Initiative. It was co-published by the Mail & Guardian here, and by the Centre for Investigative Journalism Malawi here