22 Sep South Africa (M)ainstreams wind and solar power

Independent producers are already feeding enough electricity into the national grid to replace two coal-fired power stations. Thabo Molelekwa investigates the status of SA’s ambitious renewable energy roll-out

A wind farm in Jeffreys Bay, Eastern Cape. 1,608MW will come from onshore wind farms in bid window 5. Photo: Flickr

Onshore wind and solar power feature strongly in South Africa’s renewable energy mix due to be contracted from independent producers by the end of September 2022 under the government’s rolling procurement programme.

The fifth bid window of the Renewable Energy Independent Power Producer Procurement Programme (REIPPPP) aims to secure a total of 2,583MW of renewable energy, of which 1,608MW will come from onshore wind farms and 975MW from solar photovoltaic plants.

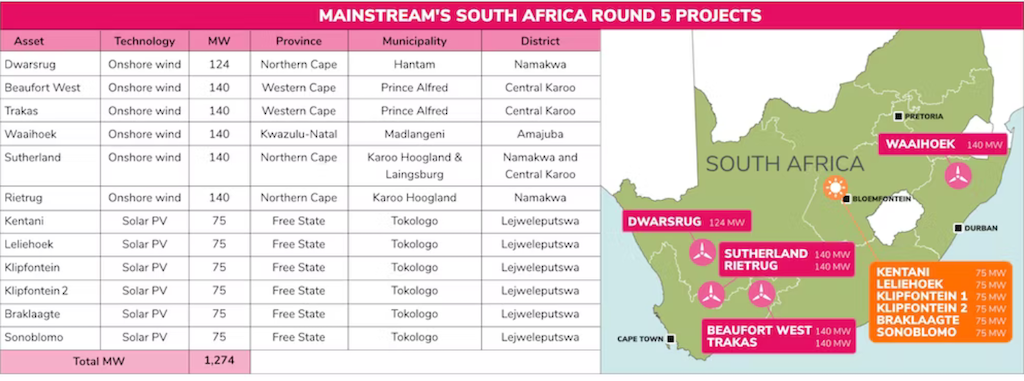

A total of 25 projects have been selected for development, and a wind and solar company called Mainstream Renewable Power succeeded in securing 12 of them. This makes Mainstream the most successful company in the history of the South African renewable energy procurement programme, with more than 2.1GW (gigawatts) awarded to it to date.

“These are completely new projects, and so they haven’t built anything,” said Wikus Kruger, research lead of power sector investment at Power Futures Lab, a centre of expertise based at the University of Cape Town’s Graduate School of Business. “They are supposed to reach the financial close deadline at the end of September.

“That is a deadline for the banks and the other investors to be satisfied with all the contracts in place. Once the risks have been dealt with, then they provide the first tranche of money for the project to start construction,” Kruger explained.

The chosen projects are expected to start generating electricity by the earliest in April 2024. Together they will produce an estimated 4,500 Gigawatt hours (GWh) of green electricity each year, helping to avoid nearly five million tonnes of CO2 per annum once fully operational.

“They will provide South Africa with critical, low-cost, indigenous power and help deliver a just transition towards its clean energy and climate goals,” says the Department of Mineral Resources and Energy (DMRE) in a statement on its website.

Minister of Mineral Resources and Energy Gwede Mantashe. Photo © Ronnie Mamoepa

Tender processes

Bid window 5 is part of a competitive tender process designed under the REIPPP to facilitate private-sector investment into grid-connected renewable-energy generation in South Africa.

Independent power producers are invited to submit bids for development of onshore wind, solar photovoltaic (PV), concentrated solar power, small hydro, biomass, biogas or landfill gas projects. Submitted bids must first qualify for evaluation by meeting minimum compliance requirements, after which they are evaluated based on price and economic development criteria.

Between 2011 and 2015 four bidding rounds, or bid windows, were completed. Competition has been fierce, with 390 submissions resulting in just under a quarter (92) selected for procurement of 6,328MW amounting to R193-billion (USD20.5-billion) in investment, according to researchers Anton Eberhard and Raine Naude in The South African Renewable Energy Independent Power Producer Procurement Programme: A Review and Lessons Learned.

Speaking at the announcement of the preferred bidders of window 5 in October last year, Minister of Mineral Resources and Energy Gwede Mantashe said the country has so far procured and signed agreements with a total of 93 independent power producer projects totalling 7,308MW.

“Eighty-nine of these projects, including bid window 4 projects signed in 2018, are already connected to the grid and are supplying 6,855MW – equivalent to two of Eskom’s coal-fired power stations. These include 86 renewable energy projects, two diesel-fired peaking plants, and five small power plants in the form of hydropower, landfill gas and biomass,” Mantashe said.

According to DMRE site, most of the responses submitted by the preferred bidders in bid window 5 were well prepared, resulting in a high level of competition. The average price of electricity that would be generated by these projects, including wind and solar PV, is R473.94/MWh.

The DMRE says this is the lowest price achieved by the REIPPPP programme since its inception in 2010 and that the average price would have been even lower if it was not for constraints on the national grid that prevented some of the cheaper projects from being selected as preferred bidders.

The department says more investment in grid infrastructure is a critical requirement to ensure participation by cheaper renewable projects in future, especially in those areas with higher solar radiation yield. The 12 wind projects selected as preferred bidders have an average price of R495.22/MWh, and the 13 selected solar PV projects have an average price of R428.79/MWh.

Development targets

As with all previous REIPPPP programmes, the fifth bid round set out a number of key economic development targets to be achieved by the bidders. In this regard, 49.2 % of the 25 projects appointed as preferred bidders are owned by South African shareholders – the desired minimum threshold was set at 49%.

The majority of the equity owned by South Africans has been taken up by black people, notes the DMRE site. On average, black South Africans own 34.7% of the equity across the different projects, while the minimum desired threshold was set as 30%.

In line with the request-for-proposals requirements, the preferred bidders committed to 25% of ownership by black people in the project construction companies. In addition, they committed to 28% ownership by black people during operation.

The Xina Solar One, a concentrated solar power plant in Upington, Northern Cape. Photo: Flickr

Who funds the projects?

The total amount awarded to these projects is R50-billion, with the majority of the projects being awarded an average of R1,564-billion.

Wikus Kruger at Power Futures Lab explained how the funding of the projects is structured: “They get awarded contracts for them to be able to sell electricity to Eskom for 20 years. So companies go to the bank and investors to raise funds.” In other words, they borrow the money.

When the government awards these contracts, it does not award any money. The companies themselves must go and look for money to fund their projects. “The money that goes into this programme is from the private sector,” Kruger told Oxpeckers.

This is a loan that will need to be repaid, he said: “The bank can determine how long the repayment period is and how much interest they charge, and the company needs to repay this loan based on their revenue.”

The developers are expected to sign project agreements with the DMRE by no later than the end of September, and to finalise their outstanding approvals, including obtaining generation licences from the National Energy Regulator of South Africa (Nersa)

The Independent Power Producer quarterly report published in June 2021 shows that the REIPPPP programme has so far attracted R41.8-billion in foreign investment and financing.

According to the report, while retaining shareholding for South Africans is a priority, the associated influx of foreign investment and funding is also significant for the economy as it reflects investors’ confidence to invest in South Africa instead of another country.

In recent years, foreign direct investment in South Africa remained at relatively low levels compared to other emerging-market countries. The REIPPPP not only brings foreign expertise to develop renewable energy projects but, the report says, also improves the country’s balance of payments by offering a fair and transparent mechanism for investors.

Financing and investments (equity and debt) originate from a variety of countries across the globe, with Europe and the United States representing the largest sources of finance.

The DMRE has already opened registrations for bid window 6. The new generation capacity to be procured from window 6 will be increased to 4,200MW, made up of 3,200MW wind energy resources and 1,000MW solar PV energy resources.

Mainstream Renewable Power will deliver six onshore wind projects and six solar PV projects. Graphic sourced

Mainstream Renewable Power

Leading a consortium named Ikamva, global wind and solar company Mainstream Renewable Power will deliver six onshore wind projects and six solar PV projects, including the first REIPPPP project in KwaZulu-Natal province. The 12 projects, according to the company, will generate enough clean energy to power a third of the annual electricity demand of the City of Cape Town.

On its website Mainstream says it manages construction activities and delivers projects into commercial operation. It provides operations and maintenance through its subsidiary, Mainstream Asset Management South Africa.

“Mainstream is the leading renewable energy company in South Africa, with over 2.1GW awarded under the REIPPPP programme to date. Since the programme commenced, Mainstream has delivered 842MW of wind and solar plant into commercial operation,” states the site.

The company was not able to answer questions about the Ikamva consortium: “Mainstream is not in a position to comment on the progress of its projects until such time as we reach commercial close,” said Andiswa Mosetlhi, Mainstream’s external relations manager.

The other 13 successful projects in bid window 5 are divided between the likes of Engie Africa, EDF Renewables, Mulilo Renewable Energy and Total energies, among others.

Minister Mantashe hosted a project agreement signing ceremony with three EDF Renewable projects on Thursday, September 22 – for its Coleskop, San Kraal and Phezukomoya onshore wind power projects, located on the border between the Eastern and Northern Cape provinces – with a combined capacity of 420MW and a combined investment value of R11-billion.

A deadline of the end of October was set for the signing of power purchase and implementation agreements by the remaining 22 projects.

Noupoort wind farm in the Northern Cape. More power lines are needed to connect projects such as this 80MW source to the national grid. Photo: Flikcr

COP26 $8.5bn commitment

At the United Nations COP26 climate change conference held in Glasgow late last year, European donor governments pledged $8.5-billion for South Africa’s Just Energy Transition programme. This commitment was built on an earlier Eskom proposal to launch a $10-billion sustainability-linked loan.

According to Wikus Kruger, the $8.5-billion commitment has nothing to do with these REIPPPP projects. The big question, he says, is what should that money be used for?

He maintains the money should not go to building more renewable energy projects “because we have enough money to do that. There are people who would like it to be used to fund these kinds of renewable energy projects. But we think that would be a mistake because the private sector, which is the banks, the equity shareholders, and the shareholders, are all very happy and willing to provide money for these projects. So they don’t need additional public funds,” he told Oxpeckers.

A big part of that money should go to coal communities in Mpumalanga that are being affected by mine closures or power plants that need to be decommissioned, Kruger added.

He also highlighted the need for more grid investment: “We need more power lines, especially in the areas where the best renewable energy resources are – and that is currently in the west of the country, Northern Cape, Eastern Cape and Western Cape, where there isn’t enough capacity on the power lines to take all the power we need. There are a lot of projects that could be connected to the grid but aren’t because we don’t have transmission lines,” Kruger said.

Children play near illegal settlements built on a former coal mine. More than $250-billion is needed to transform South Africa’s energy system from coal. Photo © Victoria Schneider/Al Jazeera

Drop in the ocean

According to recent research by the University of Stellenbosch, this $8.5-billion commitment is a drop in the ocean, representing just more than 3% of the more than $250-billion needed to transform South Africa’s energy system.

While details of this commitment are currently not clear, the research indicates that, based on available information, a majority of the $8.5-billion will either be sovereign debt channelled via different entities and multilateral trust funds, or simply “mobilised” money from foreign and private investors, with very little concessional or grant funding. This means that the total $8.5-billion will not be easily, or entirely, available or accessible on terms which create the right incentives and mechanisms to transition rapidly.

In an article published by Bloomberg on September 16 2022, Environment Minister Barbara Creecy said the details of the types of financing that will be made available and the terms and conditions attached to the $8.5-billion are still being hashed out, along with South Africa’s investment plans.

“We underestimated when this offer was made exactly how complicated it is,” she told Bloomberg. “One has partners and development institutions with different terms and conditions, and dependent on their own fiscal cycles and so on. So it’s a complicated process.”

More details regarding the commitment are expected to be discussed at the COP27 climate change conference this November in Egypt.

Thabo Molelekwa is a freelance health and climate journalist. He coordinates the climate change citizen journalism project at Heinrich Böll Foundation under the European Union Rural Action for Climate Resilience Project (RACR). This investigation was completed with the support of the Oxpeckers Investigative Environmental Journalism #PowerTracker project and the Centre for Investigative Journalism’s Open Climate Reporting Initiative. It was co-published by the Mail & Guardian here, and by IOL here