25 Mar EU’s mega-rich fuelling illegal ‘blood timber’ trade

Since the military seized power in Myanmar in 2021 and the European Union imposed economic and trade sanctions on the junta, the teak trade has been pushed underground. Sarah Tekath investigates

A logging yard in Yit Zang on the border between Myanmar and China. Photo © Environmental Investigation Agency

Teak is one of the most highly prized hardwoods in the world due to its finish and durability, and is becoming increasingly popular among the mega-rich.

It’s one of the best-known timbers and hails from the tropical forests of South Asia, where Indonesia and Myanmar have become the world’s largest suppliers.

But since the military seized power in Myanmar in 2021 and the European Union (EU) imposed economic and trade sanctions on the junta, the teak trade has been pushed underground.

Teak’s durability and robustness make it especially popular for the decks of yachts, which is why it has such an enormous price tag. For the clientele who own luxury yachts, money is not an issue. It’s all about prestige.

So the profit margins for teak dealers are high. And while EU imports are prohibited if legality and sustainability cannot be proven, the sought-after timber still finds a way on to the continent.

Illegal logging

The EU Timber Trade Regulation (EUTR), which was meant to reduce illegal logging and to ensure that no illegal wood can be sold in the EU, came into force in 2013.

It prohibits operators in Europe from placing illegally harvested timber and products derived from illegal timber on the EU market. “Legal” timber is defined as timber produced in compliance with the laws of the country where it is harvested.

To make sure all necessary rules are followed, the regulation requires operators who are placing timber on the EU market for the first time to exercise “due diligence”, for example with documentation and verified papers. However, this process depends on the national laws of each country, meaning that a pan-European procedure does not exist.

Faith Doherty, who works for the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA), says there is no legal way to import Burmese teak.

“Before the military coup in Myanmar, there were laws in place to help with sustainable logging and sustainable trade,” she says.

“One of the basic things was the annual allowable cut – how much you can log and where. From our monitoring and documentation, we could say that this was never really adhered to.”

This raises suspicions within the EIA as to how the current system is working, as there is currently no transparency or independent verification.

According to the EIA, illegal timber from Myanmar makes its way via China to the borders of the EU, where it is imported to Italy, Croatia or Greece.

Official figures from Eurostat, the statistical office of the EU, show sawn teak worth between €1.5-million and €2-million a month was imported into the EU from Myanmar in the first half of 2021.

The main importer was Italy, followed by Croatia, Poland and Greece. The figures show a decrease in imports in the latter half of the year, with monthly value of the imports falling from around €1.5-million in June to around €450,000 in November 2021.

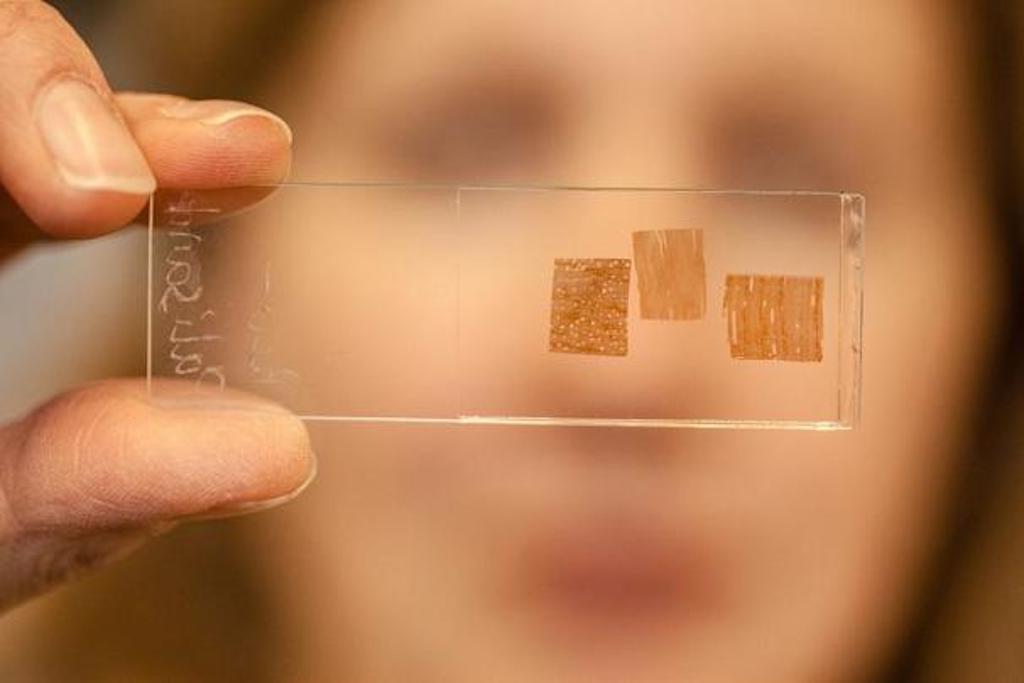

A slide containing wood samples at the Thünen Institute in Germany. If the timber was cut on the border between legal and illegal territory, it’s impossible to distinguish the difference. Photo © Thünen Institute, Germany

Genetic testing

In Germany, the Thünen Institute in Hamburg takes samples of imported timber and genetically tests them. The institute has one of the largest collections of wood samples in the world and can genetically compare them to discover where they originated from.

This method has its limits: if the timber was cut on the border between legal and illegal territory, it’s impossible to distinguish the difference.

“Genetics doesn’t stop at the border. The colleagues from the Institute of Forest Genetics only detect a difference at a distance of approximately 50 to 100 kilometres,” says Gerald Koch, from the Thünen Institute.

Not all types of wood can be tested either.

“In Germany alone, we have about 20,000 registered market participants. Not every wood product can be tested. After all, it’s not just solid wood, but also wood-based materials, fibreboard, paper and finished furniture,” he says.

“Wood is also processed into musical instruments, children’s toys, tool handles and charcoal. These are not subject to the EUTR so far.”

Logs are also mixed up in stockpiles, according to Doherty, and their markings don’t necessarily reflect their origins, making identification difficult, if not impossible.

Teak’s durability and robustness make it especially popular for the decks of yachts. Photo © Canva

Not just the mega-rich

Jeff Bezos, Amazon’s billionaire founder, currently has the world’s largest mega-yacht, built by luxury yacht company Oceanco for $500-million (€450-million).

“It is clear that teak has been used for this yacht. We are not yet sure about its origin,” says Thomas Chung from EIA. “But we know that Oceanco has used teak from Myanmar in the past.”

However, it’s not just the mega-rich who are using teak, governments are involved too.

For the renovation of their military training ship, the Gorch Fock, Germany imported teak from Myanmar, which did not comply with either the Federal Procurement Directive or the requirements of the EUTR, as stated by WWF.

WWF has filed a complaint with the European Commission. In response to queries, the Federal Agency for Agriculture and Food (BLE), which is responsible for controlling timber imports into Germany, replied: “The imports in question were made between 2015 and 2017. It was only in 2017 that the discussion about EUTR compliance of imports from Myanmar arose.”

Chung is far from satisfied with this response: “Since it is already here, we might as well use it. This is an outrageous position,” he says.

“Could you imagine if this was a pile of ivory? The outcry would be huge. But timber is always perceived as a replenishable resource, which is only partially true.”

Teak decking: the EU is working on a supply chain law to help curb the import of illegally logged timber. Photo © Environmental Investigation Agency

Possible solutions?

The only way to protect Myanmar’s teak, according to Gerald Koch, is to list it under the global Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). But, he says, this will only work if Myanmar cooperates.

“The military dictatorship will not support that because it sees teak as an important source of foreign currency.”

Another option, he says, is the monitoring of logging areas with GPS, satellites and drone technology.

Currently, the EU is working on a supply chain law to help curb the import of illegally logged timber. But all European countries would have to cooperate for change to take place.

At the same time, a Europe-wide supply chain law that is intended to encourage business responsibility and anchor corporate due diligence across sectors is under discussion.

“It’s possible that the EUTR with the current guidelines will no longer exist in two or three years,” says Koch. “But we have to see whether all partners are on board.”

This investigation by German journalist Sarah Tekath is part of a series of cross-border data-driven investigations into how the illegal teak trade from Myanmar to Europe is fuelling deforestation and propping up Myanmar’s military regime. You can follow the Rotten Routes project here.

The investigation was produced with support by a grant from the Investigative Journalism for Europe (IJ4EU) fund, and was a collaboration with #WildEye, sponsored by Oxpeckers Investigative Environmental Journalism and the Earth Journalism Network.

The investigation also appeared in Euronews Green here and Neues Deutschland here

You can follow illegal timber and other environmental crime incidents in Europe and Asia on our #WildEye tracking tools