02 Jun Philippine wildlife criminals get away with a slap on the wrist

Measly court penalties and weak laws are doing little to stop a lucrative business where kingpins evade justice, and small-time smugglers take the fall. Data investigation by Jhesset O. Enano

Environmental tragedy: Nearly 10 tons of dead and frozen pangolins were found on a fishing vessel that ran aground at Tubbataha Reefs Natural Park in 2013. Twelve Chinese fishermen were sentenced in 2014 to jail terms of between six and 12 years, and each was fined $100,000. They were released in 2016 after the Court of Appeals overturned their conviction. Photos courtesy the Palawan Council for Sustainable Development

Police officers manning a checkpoint in Tandag City, Surigao del Sur province, stopped two luxury vehicles for a cursory scan in October 2019, only to discover they had stumbled upon a multimillion-peso smuggled haul.

The three men inside the vehicles, who were from different cities in Mindanao, were transporting nearly 340 wild animals—an assortment of birds, reptiles and mammals—crammed into cages. They were unable to present any permits for their cargo.

The men said the animals were en route from Mati City, Davao Oriental province, to Pasay City in Metro Manila, a distance of more than 1,500km, but the animals could have originated from further away.

Wildlife law enforcers said the rescued species – which included 156 blue-tongue skinks, 40 sulphur-crested cockatoos and seven cassowaries – were not endemic in the Philippines and were most likely poached from neighbouring Indonesia and Papua New Guinea.

The three men were arrested and charged with illegally transporting wildlife. After three months of trial, they were sentenced by the court to pay only a fine of P5,000 (about US$100) each.

Flight risk: A peregrine falcon was among wildlife seized during an enforcement operation in August 2019 in Manila against a notorious illegal wildlife trader, who mainly does his transactions online, according to authorities. He was sentenced to imprisonment of two years and a fine of P40,000 for illegal possession and trading of wildlife, but was released on probation. He was again arrested for the same offence in 2020 and is again standing trial. Photo courtesy DENR’s Biodiversity Management Bureau

Intergenerational crime

This sentence illustrates how the Philippines struggles in its gargantuan fight against wildlife trafficking and illegal trade, environmentalists say.

Despite government efforts to step up surveillance and enforcement operations, wildlife criminals get away with mere slaps on the wrists. The measly penalties are momentary hiccups in a lucrative business where kingpins evade justice, and in the few cases of convictions, the small-time smugglers — often coerced to take on jobs with promises of easy profits — take the fall.

The difficulty in prosecuting wildlife cases stems from a myriad of challenges, from scarce resources to scant wildlife knowledge among both enforcement and judicial officers. Experts point to another weak link in the chain: the 20-year-old Wildlife Resources Conservation and Protection Act, or Republic Act No 9147.

The law seeks to conserve and protect wildlife species and their habitats, and regulate the collection and trade of wild animals. But two decades since it was passed, both government officials and wildlife experts agree that it no longer responds to the current magnitude of wildlife crime.

In the Philippines, which serves as source, transshipment and destination points for wildlife, at least P50 billion is lost annually due to the illegal trade when economic and ecosystem services are factored in, according to the Asian Development Bank.

“There is a lack of appropriate provisions under existing legislation that deals with wildlife trafficking, not only as a simple environmental crime but as a transnational crime,” said lawyer Teodoro Jose Matta, executive director of the Palawan Council for Sustainable Development, an agency attached to the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) that oversees the environmental plan in biodiversity-rich Palawan province.

“With the environmental damage that wildlife criminals do, it’s an intergenerational crime,” Matta said.

The penalties prescribed by the Act no longer serve as deterrents to big criminal networks and opportunistic poachers, according to wildlife law enforcers.

Minimum penalties

“It is kind of frustrating for us enforcers [that] after these painstaking efforts of running after the criminals, they only end up serving the least of the penalties,” said lawyer Theresa Tenazas, officer in charge of the wildlife resources division of the DENR’s Biodiversity Management Bureau.

Records from the bureau showed that out of 144 wildlife enforcement operations carried out between 2013 and 2020, only 102 cases had been filed in court. In this seven-year period, there were 31 confirmed convictions, with trial courts handing down sentences to 67 criminals. The rest of the cases are ongoing, at least based on their records, said Tenazas, but most are not updated to reflect their actual status.

The bureau, based in Quezon City, gathers wildlife enforcement reports submitted by 16 regional environmental offices and other partner agencies across the country. The government does not have a centralised database to monitor wildlife crimes and validate its success in fighting transnational offences.

Of the 31 confirmed convictions handed down to illegal wildlife traders and traffickers, data showed some received minimum jail time and fines. Under the wildlife law, penalties depend on both the illegal act and conservation status of the seized wildlife.

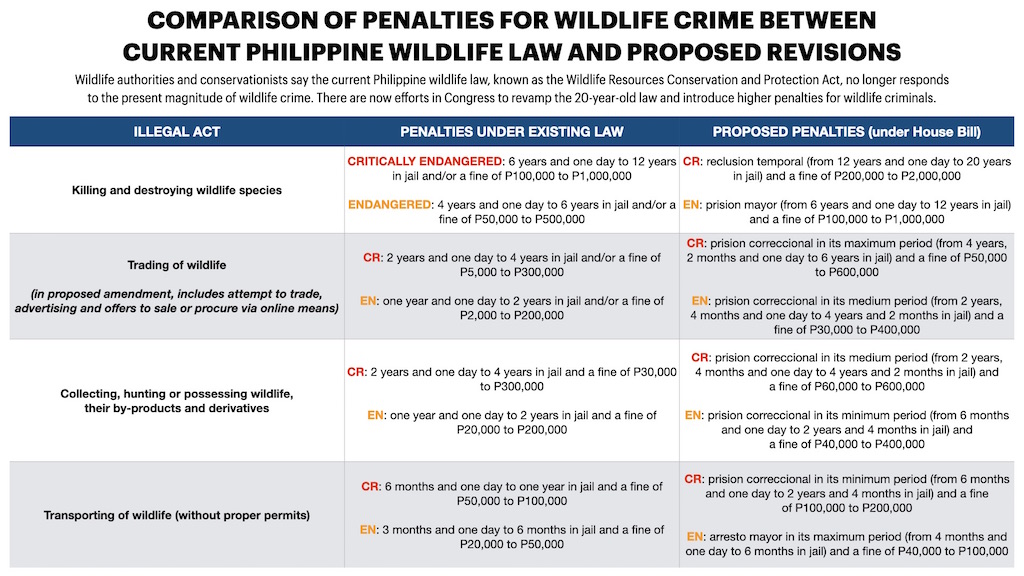

The highest penalties are meted out to those who kill critically endangered species, with imprisonment of 12 years and/or a fine of up to P1-million. For illegal trading, possession and transport, which make up the bulk of convictions, the maximum penalties are two years’ imprisonment and/or a fine of P300,000 (about $6,280).

For illegal transport of wild animals not considered threatened, the penalties can go as low as P500 (about $10) and five days behind bars.

Wildlife law enforcers say accurate identification of wildlife in case documents is crucial in determining penalties. But enforcers are often lack the scientific knowledge to identify species, and the courts often do not take into account the number of wild animals involved in a seizure when deciding the penalties.

“Let’s say you’re trading a pangolin, you still receive a low penalty even if you have 10 pieces,” said lawyer Edward Lorenzo, policy and governance adviser of Conservation International Philippines. “You’re still being charged with one act.

“Even if you sell a hundred birds, if their classification is near-threatened or vulnerable, selling or transporting them would still result in low penalties,” he added.

Endangered menu: Five people were charged after wildlife law enforcers raided an eatery in Pasil village in Cebu City that served turtle meat stew in December 2018. Nearly 95kg of marine turtle meat were confiscated. Government records do not show whether the trial court has handed down a decision for this case. Photo courtesy DENR’s Biodiversity Management Bureau

Economic incentives

In some cases, the penalties handed down are nowhere near the actual market value of the animal in possession or being traded.

Months before police officers found the cargo of nearly 340 poached animals in Tandag City, wildlife law enforcers arrested two men in Mati City, Davao Oriental province, for a similar smuggling activity.

The two illegal traders had in their possession 450 wild animals believed also to have originated from Indonesia and Papua New Guinea, like the Tandag shipment, prompting enforcers to believe that the two cases were related and involved the same network of traffickers.

The seized animals were valued at P50-million (about $1-million), but the municipal trial court handed down the minimum fine for possessing critically endangered species: two years and a day in jail and P30,000 (about $628) in fines. They were also sentenced to a month’s imprisonment and a P5,000 (about $105) fine for illegal trade.

“There is a disparity, a real gap between the economic incentives that the criminals can get in wildlife trafficking, and the disincentives given by the law,” said Matta.

“There’s also a lack of provision in our current laws to penalise accomplices and accessories… Right now, if you are a mastermind, you delegate your activity to local traders and you’re never going to get caught,” he added.

Released on probation: Philippine wildlife authorities seized nearly 450 wild animals, including sulphur-crested cockatoos and black palm cockatoos, from two men in an enforcement operation in Davao Oriental province in April 2019. The two men claimed to be mere caretakers and unaware that the wildlife was smuggled from Indonesia and Papua New Guinea. They immediately posted bail and evaded jail time after conviction by applying for probation. Photo courtesy DENR’s Biodiversity Management Bureau

Out of jail free

Most of the sentences under the current wildlife law are below six years’ imprisonment. First-time convicts often apply for probation to skip jail time and avoid paying the fines under certain terms.

In the Mati case, the two men spent only four days behind bars before posting P40,000 (about $838) bail. After their conviction, both sought probation.

According to the Davao Oriental Parole and Probation Office, the two men, who are cousins, were “very qualified” for probation because there no other criminal charges against them. The two said they were fishermen from General Santos City, South Cotabato province, who were forced to stay on shore after their boat was damaged. They said they were approached by an unnamed person to look after the birds and other wildlife — claiming they did not know they were smuggled — in exchange for P250 (about $5) a day and food.

Their bail was paid for by a relative, said senior probation and parole officer Jonaliza Manguiob, whom they asked for help after they were arrested.

Since their probation application was granted in September 2020, they have not begun their probation service nor shown up at the probation office in General Santos, where their application had been transferred. Manguiob said the men claimed difficulty in travelling because of their fishing activities. Despite their absence, no warrants have been served against them.

The same story occurs in many other cases.

In Tagaytay City, three men who smuggled 10 Philippine pangolins, among the most trafficked mammals globally, were sentenced to just three months’ imprisonment and a fine of P20,000 (about $419) each. Only three pangolins were repatriated alive back to Palawan province; seven others had died in the smuggling attempt.

Two of the smugglers were granted probation, and the other was confirmed to have ended his term last February. The third convict is on the run with an arrest warrant against him, after he failed to appear at the probation office, according to Eduardo Lamorena Jr, Tagaytay probation and parole chief.

Revising the law

These are the realities that wildlife law enforcers and conservationists hope to overturn in amending the wildlife law.

In the House of Representatives, a substitute Bill that revamps the law passed though the committee on appropriations in May after gaining approval from the committee on natural resources in December last year. In the Senate, two senators each filed a Bill in March, and these remain pending at the Senate committee on environment, natural resources and climate change.

Under the House substitute Bill, the penalties for killing a critically endangered animal could now mean 12 to 20 years in prison, on top of a fine of P200,000 (about $4,188) up to P2-million (about $41,884).

Illegal traders could face minimum imprisonment of four years and cough up P50,000 (about $1,047) in fines. Those transporting without proper permits could be sentenced to pay P100,000 (about $2,094) and spend time in jail for up to two years.

The revisions also aim to check loopholes in the current law. For instance, each wild animal seized will now constitute a separate and distinct count of an illegal act. For the first time, the definition of wildlife trafficking will include a criminal act committed by a syndicate, as well as wildlife either bound for import or export from the country.

The proposed amendments also aim to strengthen wildlife law enforcement by creating plantilla positions and deputising wildlife enforcement officers.

“This will deter criminal elements, those involved in trafficking of wildlife,” said Tenazas. “The Philippines is no longer a haven for them.”

Much remains to be done, however, in ensuring actual prosecution and conviction of wildlife criminals, conservationists say. Wildlife law enforcers, especially in the DENR provincial offices, should be trained to handle and see wildlife cases through, and not just settle for the minimum punishment.

The government must also exert efforts to wield other legal mechanisms, said Lorenzo. Wildlife criminals, especially those using electronic and online means in their transactions and those involved in transboundary trafficking, could be slapped with violations of the cybercrime law and the anti-money laundering law.

“There can be more creative ways of using these other modes to target the upper levels of the syndicates and not just the lower-ranking parts of the network,” Lorenzo said. “They’re more important since they’re the ones providing financing, logistics and connections.”

As wildlife crime persists despite continuous enforcement operations and the coronavirus lockdowns, the harsher penalties could no longer afford more delays.

“The amended law will not end anything, but I believe it can go a long way in helping us minimise our current problems,” said Lorenzo. “What we want is our enforcers to be prepared, so that when the world opens again and the illegal trade comes back, at least they are more ready.”

Jhesset O. Enano is an environmental reporter at the Philippine Daily Inquirer. This investigation was sponsored by #WildEye Asia and Internews’ Earth Journalism Network, and was published by the Philippine Daily Inquirer here.

Data used in this investigation is shared in our Get the Data section. You can track these and other cases by subscribing to alerts on the #WildEye Asia tool.