01 Apr ‘Time to shut down Koeberg’s nuclear project’

Experts say recent earth tremors in Cape Town highlight the need to shut down the Koeberg nuclear station at the end of its lifespan in three years’ time. Andiswa Matikinca investigates

Power peril? Watchdogs say the original designers of Koeberg did not fully comprehend the severe environmental attack the structures would be subjected to in a harsh marine environment. Photo courtesy Eskom

Energy watchdogs in the Western Cape say preparations for the decommissioning of the controversial Koeberg nuclear station need to start now so it can be shut down when it reaches the end of its lifespan in 2024.

The life of the nuclear plant was extended to 2044 in the 2019 Integrated Resource Plan, South Africa’s long-term energy vision. But that was before three recent earth tremors in the Western Cape raised further concerns about Koeberg’s safety.

Minister of Mineral Resources and Energy Gwede Mantashe put a damper on extension plans on Friday, March 26, when he announced safety would be a priority consideration when Eskom applies for a new licence for Koeberg through the National Nuclear Regulator.

In terms of new Regulations on the Long Term Operation of Nuclear Installations published by the minister, the cash-strapped power utility will need to prove to the regulator that it has the financial and human resources to run Koeberg for the next 20 years. It will also need to provide an overall safety assessment for the ageing nuclear station.

“It is not safe to continue with the lifespan of the plant,” said Peter Becker, spokesperson of the Koeberg Alert Alliance (KAA). The nuclear plant was designed and constructed with a lifespan of 40 years in mind and it is a big error in judgement to extend that when the utility doesn’t have access to the team that designed the plant, he said.

“The original designers did not fully comprehend the severe environmental attack the structures would be subjected to in a harsh marine environment,” Becker said.

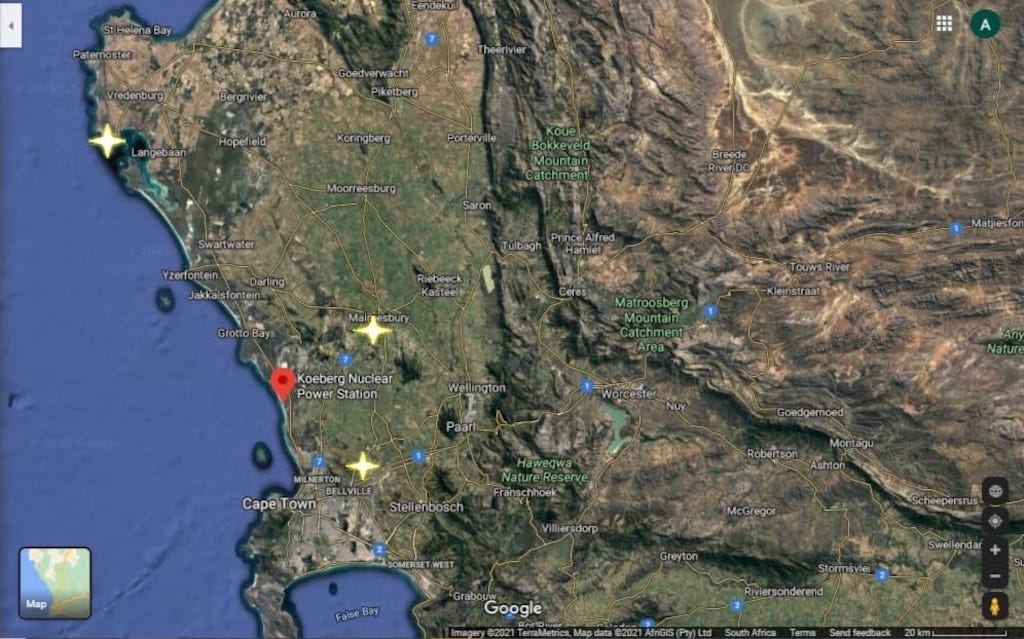

Long-running fears about Koeberg’s safety were heightened when a 2.5 magnitude earth tremor lasting three to four seconds was experienced by Cape Town residents on September 26 2020. The incident followed a 6.1 magnitude tremor that had struck 1,600km offshore of South Africa.

A second tremor caused by a magnitude 2.3 earthquake was experienced near Durbanville a day later. And on the evening of 17 November 2020, less than two months later, there was a third tremor caused by a magnitude 3.5 tremor 76km northwest of Cape Town.

Seismic risk? Satellite image showing the location of three earth tremors in 2020 that raised further concerns about the ability of the Koeberg nuclear power plant to withstand a major seismic event. Graphic: Andiswa Matikinca

Access to information

#MineAlert submitted a Promotion of Access to Information (PAIA) application to the country’s power utility, Eskom, requesting the results of a recent study into the seismic risks associated with the Koeberg nuclear power plant.

Koeberg is the only nuclear power station on the African continent and is located in Duynefontein, 27km north of Cape Town. It is owned and operated by Eskom, and reportedly supplies up to 50% of the Western Cape’s power needs.

After the November 2020 tremor, Eskom issued a media statement assuring the public “there are no safety concerns with regards to the Koeberg power station, which was designed to withstand a magnitude 7 earthquake… the amplitude of a tremor of 3.4 is much less than 0.1% of what Koeberg was designed to safely withstand.”

In its PAIA application, #MineAlert asked for a 2017 seismic risk study conducted for the Duynefontein site of the Koeberg plant. A similar request had been submitted in 2017 to the National Nuclear Regulator by the KAA, but this was rejected due to “mandatory protection of third party information in accordance with Chapter 4 of the NNR PAIA manual”.

Eskom’s information officer, Eddie Laubscher, responded to the #MineAlert application that “there was no study done in 2017”. Instead he provided a 2015 seismic hazard report which assessed the “robustness of the facility’s design to maintain its safety functions when challenged by a seismic hazard beyond the design basis”.

Parts of the report were redacted, which Laubshcer said was in line with provisions in the PAIA regulations. These redactions included personal data, information regarded as sensitive because Koeberg is a national key point, and information considered to be opinion which could “reasonably be expected to frustrate the deliberative process in a public body”.

According to the December 2015 seismic hazard report, “the seismicity of the site due to earthquake-induced ground motion was originally assessed by Dames and Moore [in 1976] and by the Council for Geoscience. The studies included an ‘assessment to evaluate the potential presence of a capable fault and also to determine if any evidence exists of a capable fault within the vicinity of the site’.”

The results of these geological investigations showed there was no evidence to suggest that tertiary or recent sediments were faulted in the Koeberg site area. This means that no rock sediments were fractured in the area, the report states.

An updated Koeberg safety report in 2005 assures that the safety systems are designed to withstand a “maximum credible seismic event, having high intensity even though it has low probability of occurrence”, the report states.

Read between the lines: A redacted internal Eskom document acknowledging that 40 years of exposure to sea air has damaged the concrete of Koeberg’s containment buildings. Infographic courtesy KAA

Another Fukushima disaster?

Watchdogs such as the KAA and the Southern African Faith Communities’ Environment Institute (Safcei) said the recent seismic activities added further fears about plans to extend the life of the plant by 20 years past its original lifespan.

KAA said in response to a PAIA application it had submitted to Eskom, it received a redacted internal document acknowledging that 40 years of exposure to sea air has damaged the concrete of the containment buildings. These enclose the nuclear reactor and are designed, in an emergency, to contain the release of radioactive steam or gas.

“The right way to do things would be to break the containment buildings and rebuild them,” said Becker, “but that is too expensive – and embarrassing, because Eskom has been saying Koeberg is the cheapest and safest energy supply and if the containment buildings are rebuilt, it would be an inherent admission that there was a risk.”

Eskom’s internal document shows the concrete containment dome at Koeberg had at one stage cracked around its entire 110m circumference. In the response, Eskom stated that the containment buildings were pressure tested every 10 years, and had passed the last test. The document did not indicate when that last test was done.

“That means Koeberg could have a leak for nine years and they wouldn’t notice,” said Becker.

Eskom responded in a February 2021 press release that it “is fully cognisant of the risk of corrosion of civil structures at Koeberg, which is a result of the station being located in a corrosive environment”. Ongoing repairs to and testing of the containment buildings had shown the structures were capable of withstanding the most severe accident, it said.

“Concrete repairs have been implemented to reinstate areas of the external façades where spalling and delamination occurred due to reinforcement corrosion in the containment buildings,” the Eskom release said.

But Becker is not reassured. Referring to previous nuclear disasters in Japan and Ukraine, he said: “Fukushima was unlikely, Chernobyl was also unlikely, and if you went to either of those plants the days before the accident and asked if the plants were safe, the answer would have been, ‘yes, of course’.

“Fukushima is the name of a province in Japan – yet now the word ‘Fukushima’ means nuclear disaster site to everyone in the world. Should a nuclear disaster of similar magnitude happen at Koeberg, the Western Cape would forever be known for the ‘Western Cape nuclear disaster’,” he said.

“That would be the end of the wine industry, the dairy industry and the end of all tourism in Cape Town. Thousands of people won’t have a home, a school for their kids and no jobs. How are we going to deal with that as a country?” Becker asked.

This #MineAlert investigation was produced with support from Oxpeckers Investigative Environmental Journalism and Code for Africa’s WanaData project