20 Jan ‘Gold rush’ as Botswana meets appetite for lion goods

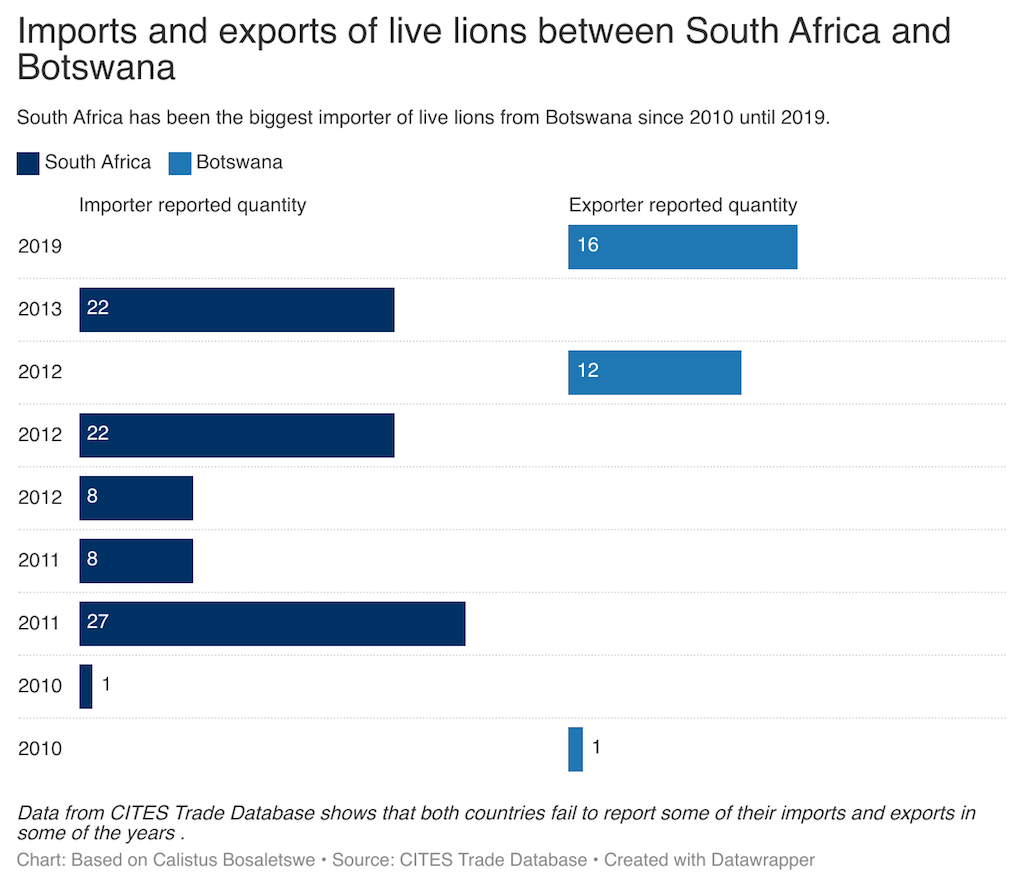

Data shows that over a 10-year period South Africa received most of the live lions and their products exported from Botswana – including 16 live lions in 2019.

Investigation by Calistus Bosaletswe

The government banned canned hunting of big cats after an Oxpeckers exposé showed the then minister of agriculture, Christian de Graaff, had exported a large shipment of lions to Makhulu game farm in South Africa. Photo © Oxpeckers

Botswana is deeply involved in the controversial export of live lions and lion products to satisfy growing international demand.

Experts fear that the legal trade in lion commodities, including bones, claws, teeth and skins, could be used as a front for illegally obtained products.

There are also concerns that the export of live animals may be linked to “canned” lion hunting in South Africa, the subject of international condemnation.

In the past, Botswana has been at the centre of uproars about the illegal exportation of lion bones to South Africa, and has controversially exported live lions to South Africa for canned hunting.

Lion products are growing in importance as a replacement for tiger derivatives in some traditional medicines in Asia as tigers become rarer and more difficult to hunt.

The products are claimed to be the result of trophy hunting, natural mortality and “problem” lions that farmers have killed in retaliation for attacks on their livestock.

Botswana continued to take part in the trade even after the previous president of the country, Ian Khama, imposed a moratorium on the hunting of the big cats in 2014. The government also banned canned hunting of carnivores, in response to an exposé by Oxpeckers Investigative Environmental Journalism that showed the then minister of agriculture, Christian de Graaff, had exported a large shipment of lions to a canned hunting outfit in South Africa. (Botswana bans canned hunts)

About 20,000 African lions are thought to remain in the wild. The International Union for the Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN) Red List now classifies them as “vulnerable”, and some experts believe that at the current rate of decimation, the big cats may be extinct by 2050.

CITES data

A trove of data from the CITES Trade Database, which is managed by the UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre on behalf of the CITES secretariat, highlights the depth of the country’s involvement.

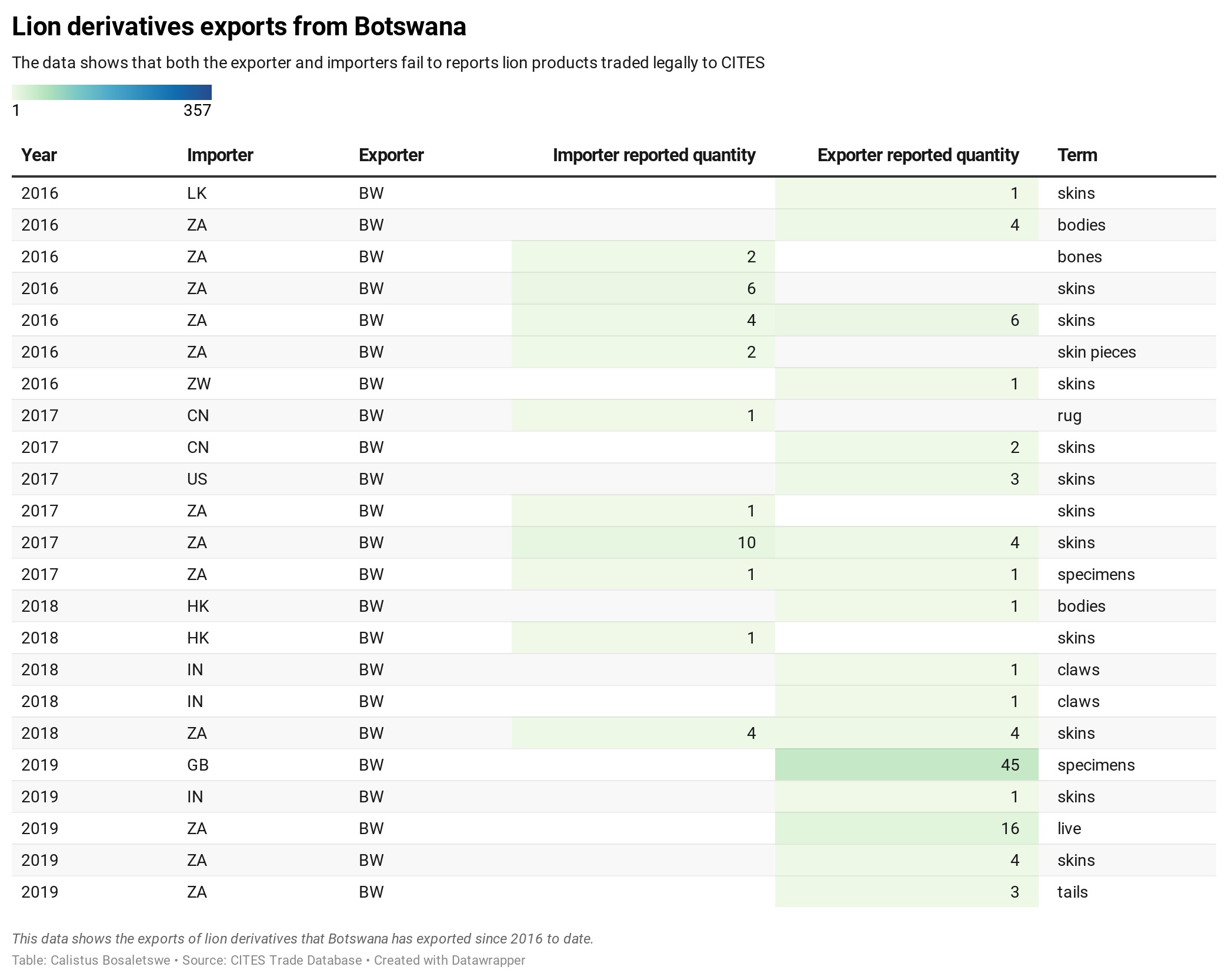

The data shows that over a 10-year period South Africa received most of the live lions and their products from Botswana, while lion derivatives went to China – the second largest consumer – Hong Kong, India and the United States.

The data shows that in 2019 Botswana exported 16 live lions to South Africa, as well as derivatives such as bodies and skins.

The exports are listed as being for personal and commercial use. It is not clear whether “commercial” indicates they went to South Africa’s canned hunting industry.

In response to questions about who exported the live lions, Botswana’s director at the Department of Wildlife and National Parks, Kabelo Senyatso, said he could not divulge the name of the farmer behind the exports, or of the South African buyers.

“The lions belonged to the farmer who exported them. We are not in a position to divulge who the lions were sold to,” said Senyatso.

Asked whether the trade could damage Botswana’s reputation for wildlife conservation, he said the exported lions would be governed by South African laws.

“Botswana cannot impose on South Africa how to manage resources within their jurisdiction,” he said.

Senyatso said the moratorium on the hunting of lions in Botswana was still in force, but denied that the exporting of live lions defeats its purpose, saying that the traded animals were bred in captivity and not hunted.

“The moratorium is on lion trophy hunting, not the export of live animals as in this case, or products from problem animal control,” he added.

He said the Wildlife Conservation and National Parks act of 1992 allows for the killing of any animal that has damaged and or is likely to damage property.

The Act requires farmers to report the circumstances of a killing and deliver trophies of the killed animal to the department or a police station. The department then carries out auctions of the dead animals and their products across the country.

Senyatso said the export of lions to South Africa was meant to address the carrying capacity of wildlife ranches and improve the gene pool.

Mind the gap: The data shows discrepancies in reporting by importing and exporting countries

Lion products

The CITES trade data base shows that the largest sale of lion products between 2010 and 2015 took place in 2013, when 126 claws were exported to China, from “problem” lions killed by farmers, natural deaths and trophy hunting – before the hunting moratorium came into place. Senyatso would not divulge the names of the three people involved in the claw exports.

The data also shows that China is not reporting the imports from Botswana, as required by the UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre. India and Hong Kong have also failed to report lion imports from Botswana such as claws, skins and bones from 2015 to the present.

China only reported importing a rug in 2017, but failed to report nine claws imported in 2015 and two skins in 2017. Hong Kong failed to report the importation of a lion body, while India did not report the importation of two claws in 2018 and a skin in 2019

A former CITES desk officer at the department, Abednico Macheme, said that dealers could choose to utilise a commercial trade quota that is available to Botswana on lion parts and derivatives. “The claws you refer to were sourced in this manner and legally traded,” he said.

He said illegal trading takes place when criminal syndicates exploit loopholes in the legal system. “This becomes dangerous when there is institutionalised corruption, either at ports of entry or source points,” he said.

“Lion derivatives became a cheaper replacement for tiger products because the overheads associated with running a captive facility are eliminated. But illegal activity from smuggling is possible based on counterfeit documents from the legal trade,” added Macheme.

“Lions are listed in the CITES Appendix II which allows for legal trade in live lions and lion products,” said Macheme.

He would not comment on the export of the 16 live lions to South Africa in 2019, because he was not aware of the circumstances.

This data-driven investigation was a collaboration between Oxpeckers Investigative Environmental Journalism, INK Centre for Investigative Journalism and IJ Hub