12 Oct Wildlife has no part in TCM, say Chinese doctors

Yuexuan Chen talks to qualified practitioners about wildlife treatments in traditional Chinese medicine, and the perceptions of Western media

Inside a TCM pharmacy. Photo supplied

Throughout the Covid-19 pandemic, Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) has been in the international spotlight as a driving force behind wildlife trafficking and infectious disease outbreaks. TCM beliefs are commonly referred to in the Western media as the reason for “exotic” animal consumption.

TCM is a 3,000-year-old medical system in China and it’s also a modern component of the Chinese government’s national development strategy. Worldwide, 80% of the population relies on traditional medicine as a primary source of healthcare, according to a 2014 study published in Frontiers of Pharmacology.

Chinese herbal medicines can include a mixture of herbs, minerals and animal ingredients. With more than 11,000 medicinal herbs used, and up to 20 herbs used in a single treatment formula, which is altered for individual patients, TCM is difficult to understand – especially for those outside China.

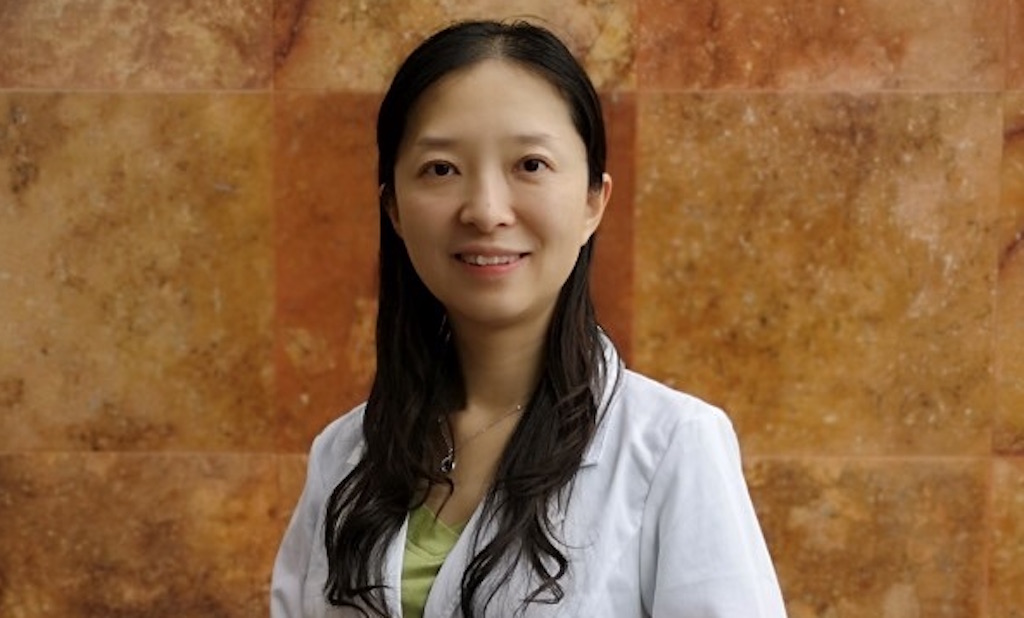

“Some TCM doctors have no formal training, but more than 90% do have formal training like Western doctors do,” said Dr Xiao Yanling, a qualified TCM doctor who practises in Washington state in the US.

“People who complete this education have no possibility of using wildlife treatments because we know they don’t work. Pangolins, bear paws and tiger bones are all things that real TCM doctors no longer use.”

Xiao is a certified oriental medicine practitioner, the only nationally recognised TCM qualification in the US, and 80% of the patients she sees are American. She also has a BsC degree in Chinese medicine from Hubei University and a Master’s degree in integrative Chinese and Western medicine from Tongji Medical College in Wuhan – the city where the novel coronavirus first emerged.

“Wildlife products in TCM hospitals do not exist,” Xiao said. “The only example of effective TCM prescriptions using animal products that I can think of is turtle shells, but it’s all farmed and it uses the leftover shells from turtles that are eaten as common delicacies.

“I have spent a lot of time in the pharmacy of various major hospitals around China and there is extremely limited use of animal parts and, when used, it’s farmed – this I can tell you with certainty.”

According to Xiao, China’s TCM manufacturing guidelines have been standardised, and where they include wildlife ingredients this is a throwback to decades ago.

Following reports linking coronavirus to illicit pangolin trade, the animals have been designated a “national first-level protection animal” and removed from the 2020 edition of the Chinese Pharmacopoeia, published by the Chinese Ministry of Health. However, Chinese news outlets report that the status of “national first-level protection” is not legally binding and does not mean these protected animals are excluded from the Chinese Pharmacopoeia.

The 2010 edition of the Chinese Pharmacopoeia set the precedent for excluding endangered animal parts such as tiger bones, rhino horns and bear bile, recommending substitutes such as artificial tiger bones instead. Even with these advances in the regulations, the Environmental Investigation Agency, an international NGO based in the United Kingdom, reports that China’s laws are contradictory and full of loopholes.

Dr Wang Erjia, a Chinese-American anesthesiologist and toxicology researcher, said where the regulations are broken and wildlife products are consumed, it is largely to flaunt wealth or show off. Superstitions that have little to do with TCM add to the appeal.

“Wild meat is also fresh tasting and has nutritional value – not in a TCM-specific way, but just that there exists nutrients like proteins in the Western sense,” Wang said.

Data collated by #Wildeye Asia indicates that Chinese courts are not accepting TCM as a reason for breaking the regulations. Six out of the eight cases heard in 2019 and 2020 involving the keeping of or dealing with animal parts as part of TCM resulted in convictions, with sentences ranging from three months to one year.

‘People who complete this education have no possibility of using wildlife treatments because we know they don’t work.’ – Dr Xiao Yanling, a qualified TCM doctor who practises in the US. Photo supplied

Eastern and Western Medicine

A Western doctor at Pingle Orthopaedics Hospital in Shenzhen, Dr Fan Peixin, works alongside TCM doctors to treat his patients.

“A combination of both west and east is best,” Fan said. “TCM is holistic and looks at the overall person, their smell, their pulse and tongue. Western medicine is acute and [attacks problems directly]. For this current virus, no Western answers have been found, but TCM has been found to be very effective according to experts,” Fan said.

Dr Zhu, a frontline TCM doctor at Wuhan Union Hospital, said TCM treatment for Covid-19 is effective in aiding recovery and preventing patients’ conditions from worsening. TCM was prescribed for more than 90% of her Covid patients and prescriptions varied depending on the patient and their condition. Few negative side-effects were recorded, she said.

“TCM is thousands of years of traditional culture and knowledge, a collection of objective observations and applications,” Fan said. “Foreigners may not be familiar with this history and tradition.”

One example of Chinese medicine meeting Western scientists was the discovery of the antimalarial Qinghaosu, also known as Artemisinin, after pharmacologist Tu Youyou scoured traditional Chinese medical herb textbooks, according to the Nobel Prize website. Tu re-discovered the recipe in a book dating back to Chinese physician Ge Hong in 340BC and was subsequently awarded the Nobel prize for her work.

All the traditional medicines at Fan’s orthopaedic hospital are herbal and are used to help patients with inflammation, pain, recovery and infection prevention. Commonly used Covid-19 TCM treatments like Lianhuaqingwen and “Pneumonia No. 1 formula” are made from various roots, fruits, seeds and herbs, Fan said.

A three-month-old baby receives a paediatric massage as TCM treatment to regulate the spleen and stomach for lactose intolerance. Photo supplied

A Place in Modern China

For Wu Huifang, a mother and journalism PhD student at Renmin University in Beijing, TCM is the preferred treatment for herself and her child. From her kid’s high fevers to minor colds to herniated disks, TCM has helped her family, she said.

What spurred her enthusiasm for TCM was an infection on her face in middle school. Her family spent 260 yuan on Western medicine when her father’s monthly wage was 300 yuan. The treatment didn’t work, so her mother found a self-taught TCM doctor who was a railroad labourer. Three traditional prescriptions cost her 30 yuan and cured her ailment.

“TCM is personalised and has roots in the community,” Wu said. “Most Eastern medicine seekers will go West, but not always the other way around. In my friend group, some do not recognise TCM, but most people find both to be useful.”

Most Western hospitals in China have a TCM department, Dr Xiao said, which is a “very essential department for both small clinics and big hospitals”.

Jimmy Ouyang, a student at Jiling International Studies University in Changchun, said he mostly visits Western doctors, but goes to TCM doctors for minor illnesses and chronic ailments. He thinks superstitions that Chinese people tie to TCM help to fuel poaching even though there are non-animal-based alternatives and evidence that wildlife products simply do not work.

“What’s dangerous is healing and life-saving traditions getting thrown out,” Wu said. “I personally feel that Western medicine doesn’t fit China. In such a large population, there’s not enough medical equipment and resources to solve all problems with Western medicine, especially in third-tier cities and villages.” (Tiers are hierarchical classifications of cities in mainland China based on development factors such as population and wealth.)

Acquiring illegal, wild products for medicinal purposes in China is out of reach for the average Chinese person’s budget. Herbal traditional medicine for Covid-19 costs around 10 RMB for each treatment, but the same medicine with pangolin scales added costs hundreds of RMB. A treatment regime that has wildlife products in it costs more than most Chinese people’s monthly salaries.

“In the cities, it’s becoming very expensive to see highly qualified TCM doctors, which isn’t how it should be because TCM should be for laobaixing – the common people,” Wu said.

Yuexuan Chen is an Oxpeckers Associate and a fourth-year student at Duke University in the US, studying public policy and biology with a journalism certificate

- Track court cases on wildlife crime using the #WildEye Asia tool