14 Jul Following South Africa’s mining millions

A data-driven #MineAlert investigation shows that 10 UK-based companies paid out at least US$1.076-billion to South African government and community entities in 2018. Andiswa Matikinca investigates where the money went

Transparency needed: According to a 2018 Corruption Watch report, ‘the pay-out of mining royalties has become distorted, unequal, and open to abuse and misuse’. Photo courtesy ActionAid SA

Ten publicly listed British companies with mining projects in South Africa reported paying out at least US$1.076-billion to government and community entities between July 2017 and December 2018.

Mandatory disclosure regulations which came into effect in the United Kingdom in 2015 require publicly listed companies that operate in the petroleum and mining sectors to disclose the amounts they pay to governments in countries where they operate.

The 2018 South African payments were for tax, royalties, infrastructure improvement, mining and other licence fees, as well as payments towards custom and excise duties and property rates and taxes, according to data hosted by Resource Projects.

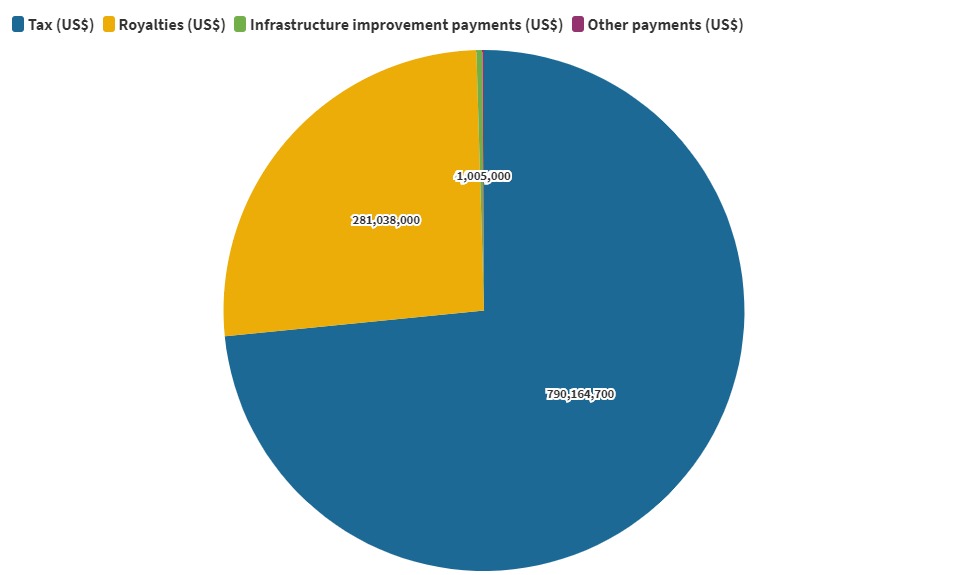

Analysis of the payment data disclosed by the 10 companies showed that a total of $790.1-million went towards taxes, $281-million towards royalty payments, $4-million towards infrastructure improvement, and just over $1-million towards “other payments” which include customs and excise duties as well as property rates and taxes.

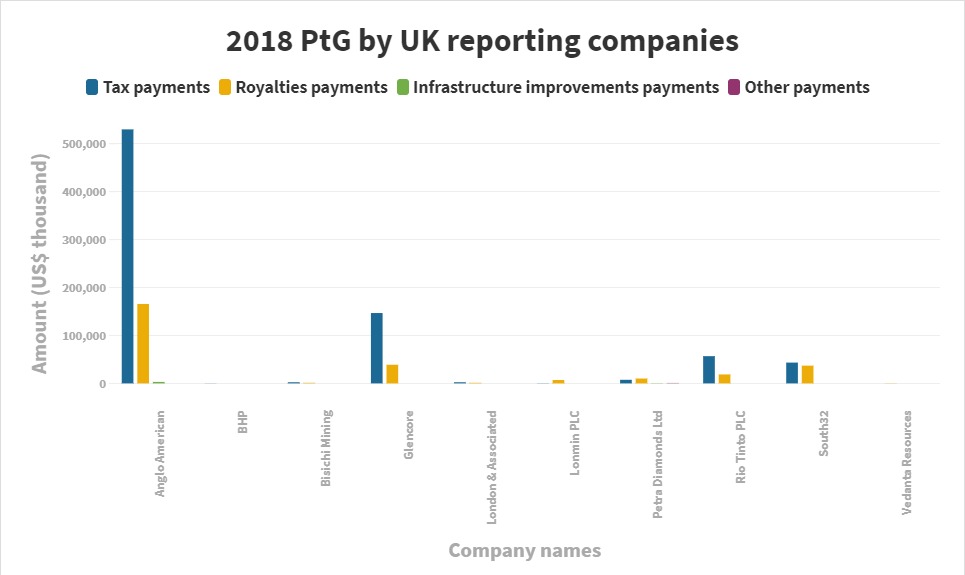

The 10 listed companies, their projects and reported payments were:

Anglo American paid out $698.7-million;

BHP Billiton paid out $292.7-000;

Bisichi Mining – Black Wattle Coal Mine (Mpumalanga) – paid out $3.8-million;

Glencore paid out $185.7-million;

London and Associated Press, which has a 41.5% interest in Bisichi Mining and its Black Wattle Coal mine, paid out $3.8-million;

Lonmin paid more than $7.7-million. The mines were Akanani Platinum Mining (Limpopo); Eastern Platinum Mine (North West); Pandora Joint Venture (North West); Western Platinum Mine (North West); Messina Platinum Mine (Limpopo);

Petra Diamonds Limited paid out over $19.5-million. The mines were Cullinan Diamond Mine (Gauteng); Finsch Diamond Mine (Northern Cape); Kimberley Ekapa Joint Venture (Northern Cape); Koffiefontein (Free State);

Rio Tinto – Richards Bay Minerals (KwaZulu-Natal) – paid out $75.5-million;

South32 paid out $80.4-million. Its South African Energy Coal operations were Khutala Colliery; Klipspruit Colliery; Wolvekrans Colliery (Mpumalanga); South African Manganese (Northern Cape);

Vedanta Limited Resources – Black Mountain Mining (Pty) Ltd – paid out $702,000.

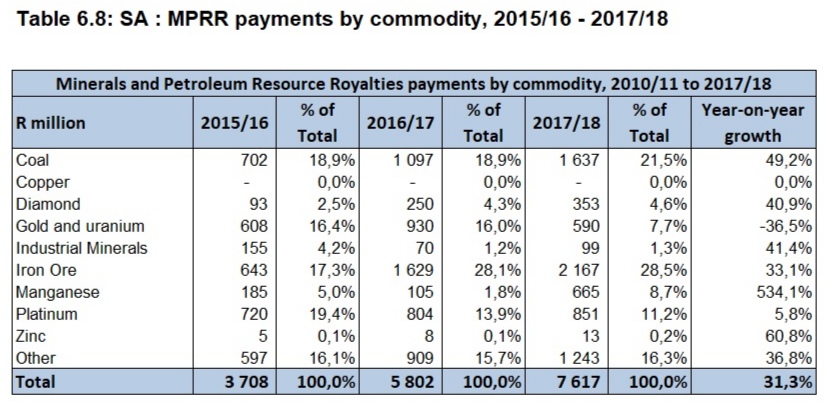

Iron rules: Royalty payments made by different mining sectors to SARS in 2015/16 and 2017/18. Graphic courtesy SARS

South African legislation

The Minerals and Petroleum Resources Development Act of 2002 (MPRDA) recognises mineral and petroleum resources as belonging to the nation, and the state as their custodian. In terms of the Act, the minister of mineral resources in consultation with the minister of finance determine the fees to be paid to the state for resources mined by different companies.

Mining royalties are classified in two forms, one being state royalties that are paid out to SARS and the other being contractual royalties that are paid to the owners of the land as part of an agreement between them and mine host communities.

SARS collects all the state royalties, which are paid into the National Revenue Fund and are allocated for different purposes by the National Treasury on an annual basis. “Royalty payments” are allocated to the government, and “contractual royalties” are payable to the owners of the land, including communities.

Asked where the 2018 payments went, and how decisions were made about where they were allocated, the National Treasury said: “As per the majority of tax instruments that South Africa uses to raise tax revenue, mineral and petroleum royalties are not earmarked for a specific spending programme (or, in this case, for mining communities)”.

According to the Treasury’s media team, although royalty payments are classified as “non-tax revenue” – meaning that they are revenue not directly generated from tax – they are still “paid to SARS by mining companies and flow into the National Revenue Fund, along with other tax revenue”.

“Government decides on an annual basis how best to spend the total revenue collected in the National Revenue fund – based on government’s objectives and priorities”, said the Treasury team.

Recent Tax Statistics jointly published by the National Treasury and SARS show that the revenue collected in the 2017/18 financial year for mining and petroleum royalties was a total of R7,617-million, and R8,612-million in the 2018/19 financial year.

The commodities that brought in the most revenue in the 2017/18 financial year were iron ore (28.5%), coal (21.5%), platinum (11.2%), manganese (8.7%), gold and uranium (7.7%).

The remaining payments would have been paid as contractual royalties to the owners of the land, including communities. However, questions sent to local municipalities who would have received some of these payments on behalf of the communities, asking for confirmation of whether the disclosed payments had been received and allocated for their intended purposes including for the benefit of the communities that host the mining projects – remained unanswered.

Questions were sent to the seven of the 10 companies about which entities they made their reported payments to, and whether any payments were made directly to mine host communities or community trusts.

The head of sustainability engagement at Anglo American, Hermien Botes, said companies did not have direct control over the royalty payments once they were handed over to the state, and the revenue sharing system of community development trusts could be tricky.

“They [community development trusts] are intended for community benefit and are managed by those communities. We work with them to improve governance, but do not have direct control,” said Botes.

Four of the companies – Bisichi Mining, London and Associated Press, Rio Tinto and South32 – did not respond. Four companies provided feedback on their royalty payments and how they were spent.

Payouts breakdown: the payments made by the companies were for tax, royalties, infrastructure improvement, mining and other licence fees. Graphic: Andiswa Matikinca/Flourish

Petra Diamonds

Four of Petra Diamonds’ South African mining projects reported making payments of just over $19.5-million. These payments were spread across the Free State, Northern Cape and Gauteng provinces, and were paid directly to SARS, local municipalities and local schools. The payments made were for taxes, royalties, infrastructure improvements and “other” payments.

Marianna Bowes, spokesperson for Petra, said mining royalties are paid directly to governments and are declared annually.

In addition, she said, Petra dedicated a “social spend” of about $1-million in 2018 that was governed by its approved Social and Labour Plans (SLPs). SLPs are one of three key documents that mining companies need to draft and submit to the Department of Mineral Resources when applying for a mining right in a certain area.

The “social spend” was paid directly towards the completion of agreed projects and programmes with local host communities where the majority of the mines’ workforce comes from, Bowes said.

Govan Teteme, chairperson of the Northern Cape Mining Affected Communities in Action, is a resident of the Danielskuil community situated near the Finsch Diamond Mine owned by Petra Diamonds. Teteme agreed that some of the developments reported by the mine have been implemented, including road and infrastructure improvements and the sponsoring of local schools.

Unemployment remains a burning issue for the community, however, and they have not benefited much from the SLP agreements that the mine made with the Department of Mineral Resources and Energy.

“We want development in the community through skills training that will target the issue of high unemployment. We need skills that enable us to be employed by the mine,” he said.

Who spent what: Where the payments to government (PtG) by the 10 companies were intended to be spent. Graphic: Andiswa Matikinca/Flourish

Lonmin

Lonmin’s operations were acquired by Sibanye-Stillwater in 2019. Lonmin’s financial records showed it paid $6-million in income tax for the 2018 financial year, a total of $1-million was paid in prepaid royalties (overseas tax), and a financial investment of $103.5-million was made to community programmes.

The community financial investment, or social spend, was reported to have been directed towards community education programmes in schools, skills development, sports, arts and culture, community health programmes (including school nutrition), basic community services, supplier development and other corporate social investment-related spend.

The 2018 financial report also mentioned that two community trusts with 0.9% shares in both the Eastern and Western Platinum Limited operations had been formed in 2014 and both were entitled to dividends from the operations’ earnings.

Asked whether the company tracked how these payments were spent, the senior vice-president for investor relations at Sibanye Stillwaters, James Wellsted, said as far as he was aware taxes and royalties paid to the government by law do not go directly to mining communities, but into the national purse.

“I’m not aware that Lonmin tracked how the money they paid to trusts was spent unless they had representatives on the boards of the trusts. Unfortunately the trusts are subject to various confidentiality agreements,” Wellsted said.

Community member and chairperson of the Sikhala Sonke Women’s Organisation, Thumeka Magwangqana, is a resident of Wonderkop town in North West province. She holds a qualification in Early Childhood Development obtained through a school programme funded and developed by Lonmin.

Magwangqana said the mining company’s contribution has been fairly visible to some parts of her community. After having talks with Lonmin and attempting to hold them accountable to their SLP commitments, Magwangqana said they received a donation of equipment from Lonmin to support some of her organisation’s development projects.

“There are many different stakeholders and organisations from the community who engaged with Lonmin, but I cannot say that everyone has benefited the same,” she said. Khalamntwana informal settlement, for instance, does not have basic services such as electricity and running water – proof that not everyone benefits equally from the mines, she said.

Helping hand: Vedanta reported contributing R108.9-million towards community development in 2018 via an employee share ownership programme managed by a trust. Photo courtesy Vedanta/Black Mountain Mining

Vedanta

Vedanta’s Black Mountain Mining reported paying $702,000 to SARS in 2018. Vedanta Zinc International’s business analyst, Hein Pienaar, said “these financial resources are managed at a national government level, according to their development plans and priorities”.

Black Mountain’s Social and Labour Plan (SLP) Close Out report for 2014 – 2019 stated that the employees of the company have a 6% ownership of the company via an employee share ownership programme called the “Voorspoed Trust”, which had contributed R108.9-million towards community development in 2018.

“Black Mountain Mining submitted a draft new five-year SLP to the DMRE in September 2019, for the period 2019 – 2023. This document has not yet been approved by the regulator and cannot therefore legally be made public until such time as formal approval has been received from the DMRE to do so,” said Pienaar.

Ina Basson, who lives close to Vedanta’s Black Mountain Mine and is a member of Northern Cape Mining Affected Communities in Action, said residents have not seen much compliance with the mine’s community commitments. It had committed to funding tourism development in the community, yet nothing had happened since 2013.

“The only thing the company has done so far is to pay stipends for Early Childhood Development teachers at pre-schools in the community,” she said.

According to Basson, community requests that have been sent to the mine through memorandums include road upgrades, building of schools, and supplying the community with water as some of the mine’s water pipelines run through the community. These requests have also been shared on the local municipality’s development plan, but to date none of them have been met, she said.

Transparency needed

In 2018 research by Corruption Watch on mining royalties highlighted that “the pay-out of mining royalties has become distorted, unequal, and open to abuse and misuse”.

The research focused on a number of mining projects in two of South Africa’s provinces, North West and Limpopo, and found there was a lack of transparency around the negotiation and conclusion of mining royalty agreements with mine-affected communities, as well as with the conversion of mining royalties arrangements from one form to another – such as the conversion from development accounts for beneficiaries to equity sharing with communities – and the withholding of mining royalties by companies.

“The key challenge which hinders royalties reaching host communities is the manner in which tax royalties are collected and shared between stakeholders, and the lack of transparency,” senior legal researcher at Corruption Watch, Mashudu Masutha, told #MineAlert.

“The structures put in place in order to ensure host communities are partners in the ecosystem of mining, including SLPs and the transformative codes of good practice for broad-based black economic empowerment, are grossly mismanaged and maladministered,” she said.

Greater transparency with regards to revenue coming into the public purse and regarding the value of commodities on host communities’ land is needed to ensure mining royalties benefit mine host communities, Masutha said.

“More stringent requirements on accountability mechanisms are needed,” she said. The DMRE should also have its own reliable, publicly accessible repository of information on mineral licence holders and mineral rights applicants in order for us not to depend solely on the private sector for information on the value, density and spectrum of our mineral resources.”

The initial data collection process was done in partnership with the Publish What You Pay South Africa coalition, of which #MineAlert is a member, Publish What You Pay UK and Global Witness as part of collaborative research on mining companies’ payments to governments and local community benefits in South Africa.

• This investigation for #MineAlert was developed with the support of Oxpeckers Investigative Environmental Journalism, Finance Uncovered and the Money Trail Project

• Use the #MineAlert digital tool to find data on these and other mining projects around SA. Related data sets are shared in the Oxpeckers Get the Data menu