05 May Chinese courts treat pangolin offenders lightly

Data investigation by #WildEye Asia exposes lenient punishments for pangolin offences that are unlikely to deter illegal trade. Investigation by Bao Choy

In early March 2020 the Chinese authority undertook a joint force action and confiscated 820kg of smuggled pangolin scales. Photo courtesy Chinese Customs

Court sentences imposed on offenders convicted of pangolin crimes in China from late 2019 to April 2020 are “non-threatening” and will not provide a deterrent to the illegal trade, say environmental activists.

Data collated by #WildEye Asia shows that, of the 34 criminals convicted of pangolin-related crimes since late 2019, close to half were given suspended sentences of less than a year. This meant they did not serve a prison term, though in all cases they received a fine.

For instance, 69-year-old Li Qigai from Guangxi region killed a Malayan pangolin smuggled from Vietnam. Li and two accomplices cut the pangolin’s throat and peeled off its scales. The meat and viscera were ground into powder, and the blood was used for soaking rice as a “Chinese medicine”.

A judge at the Jingxi People’s Court in Guangxi found Li guilty of killing rare and endangered wildlife – pangolins are listed in China as a second-grade protected species. Under criminal law, he could have been jailed for up to three years in jail and a fine.

Yet, taking into consideration that Li had confessed to his crime, on January 17 2020 the court imposed a jail sentence of five months suspended for a six-month probation period, and a fine of 3,000 renminbi ($425). The outcome was that Li had to pay his fine, but was released and would only serve his prison sentence if caught committing a similar crime during the probation period.

Environmental activists in China say this “non-threatening” sentence represents the tip of the iceberg. Despite the international ban on pangolin trade since 2016, an estimated 195,000 pangolins were trafficked in 2019 alone.

The rampant trafficking in and human consumption of pangolins has been linked to the outbreak of Covid-19 in recent studies that have suggested pangolins are the probable intermediary host of the coronavirus that jumped to infect humans.

‘Lenient punishments’

Verdicts in 25 pangolin-related criminal cases involving 34 defendants from late 2019, when the pandemic became a global problem, to April 2020 were published at Chinese Judgement Online, a government database of court rulings. Most cases occurred in Yunnan and Guangxi, the two southwestern provinces that share borders with Vietnam, Laos and Myanmar.

All these cases investigated individuals involved in first-hand selling/buying, rather than the smuggling supply chains. Out of the 34 defendants, 15 were given suspended sentences of less than a year, seven received suspended sentences of more than a year, and the remaining 12 went to jail for periods ranging from eight months to 10 years.

Liang Zhiping, a Chinese legal expert who is familiar with the Wild Animal Conservation Law, said he could not comment on particular court cases and sentences. In general, he described protecting wildlife in the country as “very difficult”.

“The penalty is heavy as written by law. But the incompetence of law enforcement, the lack of substantial evidence, the lenient punishments – including sentencing with probation – is letting a majority of criminals go,” Liang said.

The criminal law (Article 341) stipulates: “Those who illegally hunt and kill rare and endangered wild animals which are under the state key production plan, or illegally purchase, transport or sell those rare and endangered wild animals and their manufactured products, are to be sentenced to not more than five years of fixed-term imprisonment or criminal detention, and may in addition be sentenced to a fine.

“In serious cases, law offenders are to be sentenced to not less than five years and not more than 10 years of fixed-term imprisonment, and may in addition be sentenced to a fine. In especially serious cases, law offenders are to be sentenced to more than 10 years of fixed-term imprisonment, and in addition be sentenced to a fine and confiscation of their properties.”

Another example involved a 20-year-old suspect named Bao Fanduo who was arrested in December 2019 for smuggling almost 20kg of pangolin scales from Guinea to Shanghai. The 20kg of scales indicates at least 40 pangolins were killed, given that one pangolin can produce about 500g of scales.

Bao claimed he merely helped a friend by transporting the scales to China, and thus the court ruled he was an accomplice. Considering his confession and that he was a young father, the court sentenced him on December 26 2019 to three years’ imprisonment suspended for four year, and a fine of RMB60,000 ($8,485).

“The sentences are just too lenient and non-threatening to stop this illegal trade,” said Sophia Zhang of the China Biodiversity Conservation and Green Development Foundation. “In recent years our organisation has observed a trend of light punishment related to pangolin crimes due to the loopholes in existing laws.”

One of the loopholes, she said, is the ambiguous definition of “manufactured products”. According to verdicts in a pangolin-related crime in 2016, two main criminals were convicted of illegally purchasing, transporting and selling 37 dead pangolins. In the first trial in the lower court, the Heshan District People’s Court in the city of Yiyang in Hunan Province, they were sentenced to 11 years and 10.5 years respectively.

However, when the case was appealed in the Yiyang Intermediate People’s Court, the 37 descaled pangolins with their viscera removed were categorised as “manufactured products”. As a result the sentences were reduced by almost half – to 6.5 years and 5 years respectively.

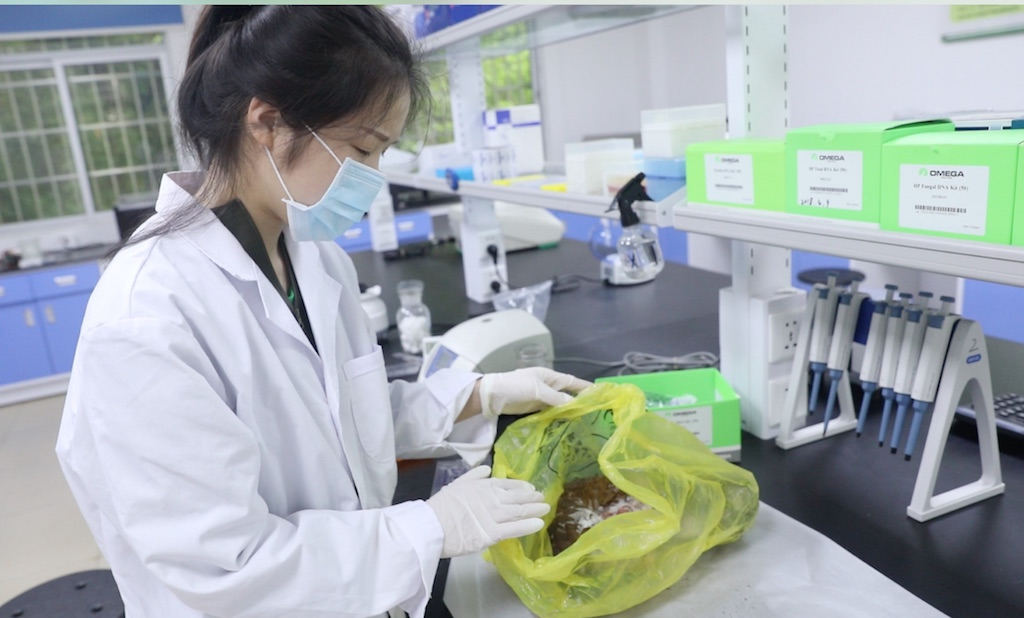

In early 2019, 21 Malayan pangolins seized by Customs officials were sent to Guangdong for rehabilitation. Within a month 16 of them died. Sophia Zhang checks the dead bodies. Photo courtesy China Biodiversity Conservation and Green Development Foundation

New laws

The Covid-19 pandemic prompted the 13th National People’s Congress Standing Committee to ban wildlife consumption in late February 2020, and provinces and cities have since followed by drafting new legislation to prohibit eating wild animals.

Under the new law, due to come into force on May 1, any individual convicted of eating state-protected animals or products faces a fine of five to 20 times the value of the animal; people who organise the eating face fines of 10 to 20 times the value. If the animal is not state-protected, the fine for an individual is one to five times the value of the animal; for people who organise the eating, the fine is three to five times the value.

Conservationists are also expecting a revision of the “List of Wild Animals Under State Priority Conservation”, which has not been updated since 1988. Zhang said there were calls to upgrade the pangolins’ status from Grade 2 to Grade 1 for tighter protection.

Since mid-February, the Chinese authorities have undertaken joint-force operations to crack down on wildlife trade in known hot spots. Details of more than 50 raids have been announced, including two large-scale crackdowns on pangolin trade.

In early March customs officers and local police raided a suspected smuggling syndicate at Guangxi and Anhui. They seized 820kg of pangolin scales, and arrested nine suspects. Then in April, another smuggling syndicate at Chongqing, Guangxi, Anhui and Sichuan was bust: 441kg of pangolin scales were confiscated and 12 suspects arrested.

There were also stiffer sentences in two cases: in early April The Shanghai High People’s Court announced that a certain Li (no full name given), who smuggled 110kg of pangolin scales from Guinea to Shanghai, was sentenced to seven years in jail and a fine of RM100,000 ($14,140). The Supreme People’s Court announced that on March 10 a man named as Chen, who had illegally bought 80 dead pangolins in Guangzhou, was jailed for eight years and fined RMB50,000 ($7,070).

Sophia Zhang checks on a pangolin in her organisation’s rescue centre in Guangdong province. Photo courtesy China Biodiversity Conservation and Green Development Foundation

Legislative reform

Despite the increasing momentum in China to crack down on wildlife crime, legal expert Liang Zhiping said he was not “too optimistic” about comprehensive legislative reform. He pointed to grey areas in the new prohibition, which exempts trade in wildlife for medicinal purposes, fur or scientific research. Aquatic wildlife is not included in the ban either, while the status of reptile and amphibian species remains unclear.

Exemptions for medicinal purposes should be endorsed by a system of “strict examination and approval procedures”, but data from past experiences show these exemptions create loopholes for traffickers to sell wild animals.

Although global wildlife trade regulator CITES introduced an international ban on trade in pangolins in January 2017, more than 200 pharmaceutical companies in China are still using pangolin products for 60 commercial traditional Chinese medicines that claim to offer remedies such as helping to reduce swelling and lactation, and improving blood circulation, according to a study by the China Biodiversity Conservation and Green Development Foundation in 2019.

The legislation process in China is ongoing amid consultation with various stakeholders.

Liang said “powerful vested interests” are pushing for the law to distinguish between “non-edible” and “edible” animals. They want the wild animal breeding industry to fall under categories which could be excluded from the ban, such as “poultry”, “aquatic”, “medicine” or “fur” so their businesses will not be affected.

According to a strategic report published by the Chinese Academy of Engineering, more than 14-million people were working in the wild animal breeding industry in 2016. The industry had contributed more than RMB520-billion ($73.4-billion) to the Chinese economy.

“This may undermine the efficacy of the law to protect species from inhumane practices and prevent public health crises,” Liang said.

• Track these and other cases on #WildEye Asia

Bao Choy is an award-winning investigative journalist based in Hong Kong and a member of the Environmental Reporting Collective. Jiaming Xu, a lead reporter of The Pangolin Reports, also contributed to the story.

This investigation was featured in China here, and was discussed in a webinar on how to become a top wildlife journalist. Sponsored by #WildEye Asia and Internews’ Earth Journalism Network.