27 Feb New mining threat at Mapungubwe heritage site

A rush of coal prospecting applications raises new fears about mining around Mapungubwe National Park, a world heritage site of cultural and environmental importance. Yolandi Groenewald investigates

Mining threatens the transfrontier conservation area that already has too many elephants for its shrinking space. Photo: Yolandi Groenewald

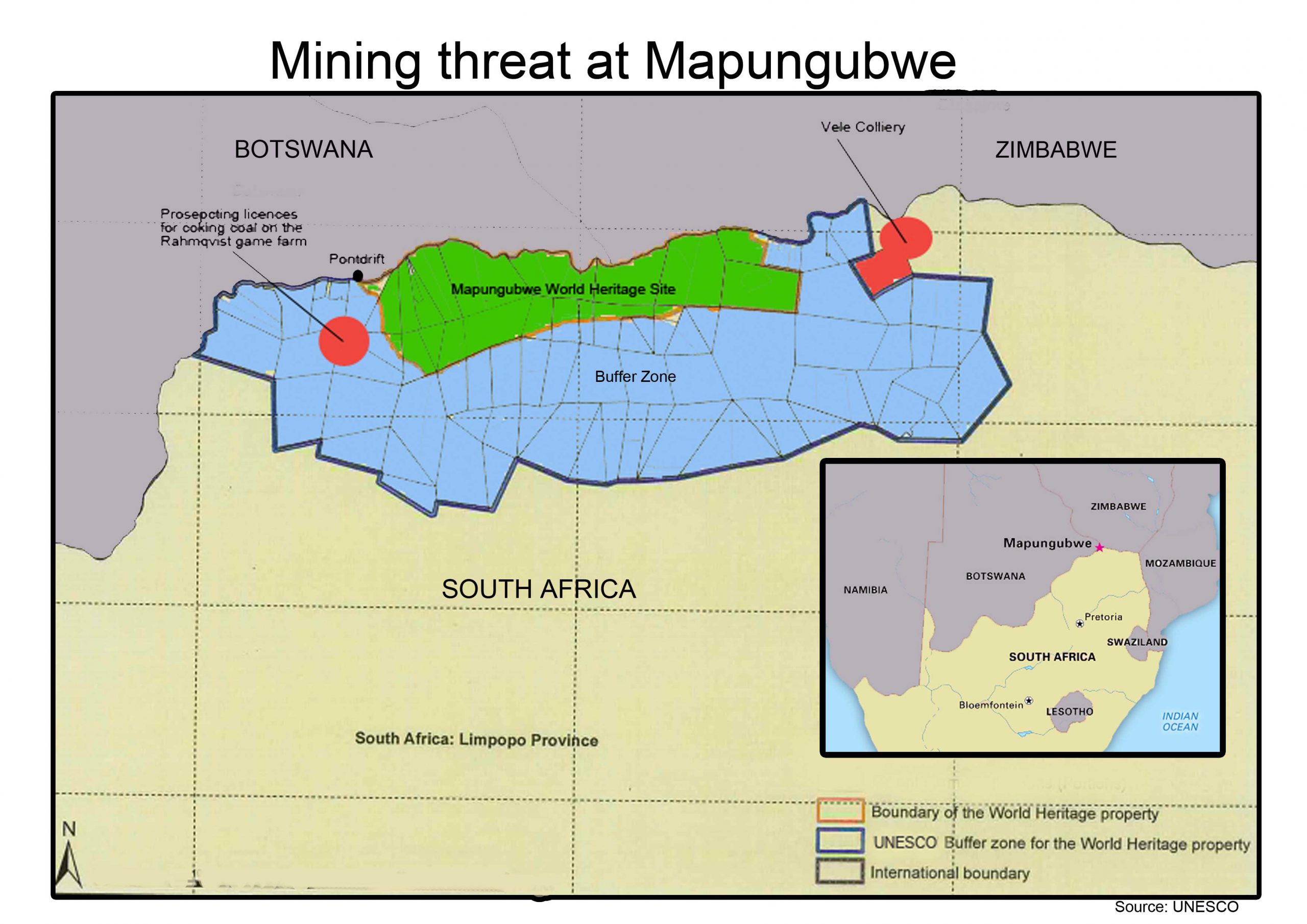

At least 23 prospecting licences have been granted around the edges of Mapungubwe National Park, and mining companies are moving in to exploit a rich coal seam running through the world heritage site.

Oxpeckers has established that at least one of the licences fall within a no-mining buffer zone set up around Mapungubwe by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (Unesco).

The prospecting is taking place in one of South Africa’s most water-stressed regions. Water from the Limpopo river is already overcommitted, regional droughts are the norm, and environmentalists have been asking for years where the water will be found for mining activities that could result from the prospecting.

Mapungubwe National Park, one of South Africa’s nine world heritage sites, lies smack in the middle of a coal seam of precious coking coal that runs from Zimbabwe to South Africa. A world-famous 800-year-old gold rhino statuette was unearthed at the site in 1933, and Mapungubwe was inscribed on the Unesco World Heritage List in 2003.

Unesco does not allow mining in heritage sites and requires a buffer zone around a listed site where no mining can take place. In the case of Mapungubwe, this requirement was tested nearly a decade ago, when Australian company Coal of Africa established its Vele Colliery in the buffer zone.

Coal of Africa, known as MC Mining since 2018, was not the only company sniffing around Mapungubwe. A prospecting licence was granted to Micawber 639 in 2009 allowing it to prospect on farms that fall within the buffer zone approved by Unesco.

Micawber stated in its application for the prospecting licence that it was owned jointly by Aphrodeities Mining, a local 100% BEE-compliant company, and Canadian mining company Takara Resources. Wendy Nqenqa, the chief executive at Aphrodeities Mining, was regarded as a rising star in the mining industry in the late 2000s, although she has been quiet of late.

Micawber has since entered a joint venture with Indian mining company IG Resources, according to two sources who did not want to be named. Oxpeckers unearthed evidence of a dispute between the two companies in the Johannesburg High Court in 2016, though the status of their current relationship is unclear. Neither company responded to requests for comment on the Mapungubwe venture.

The world-famous 800-year-old gold rhino statuette was unearthed at the Mapungubwe heritage site in 1933. Photo courtesy Solve

Official records

Ayanda Shezi, spokesperson for the Department of Mineral Resources, said official records show 23 prospecting licences have been granted in the vicinity of Mapungubwe World Heritage Site.

South African National Parks (SANParks) spokesperson Rey Thakhuli said it was aware of at least five prospecting licences near the national park and had brought them to the attention of its mother body, the Department of Environment, Forestry and Fisheries (DEFF).

“It will be handled at the departmental level. SANParks only gets involved at a commenting stage as an interested and affected party,” Thakuli said. He did not want to comment on the Micawber prospecting licence, saying prospecting and mining applications are dealt with on a case-to-case basis.

The DEFF did not respond to questions from Oxpeckers, despite being given several weeks to do so.

Farmers and landowners in the area confirmed that vast amounts of coking coal, also known as metallurgical coal and required for heating in the production of steel, had been found. They fear it is only a matter of time before mining starts.

The remoteness of the area and Vele’s financial problems had dampened the enthusiasm of the miners to commence with new projects, but the development of Limpopo’s flagship Musina-Makhado Special Economic Zone (SEZ) a few kilometres away from Mapungubwe will create the necessary infrastructure to support coal mining in the area, the sources on the ground said.

Vele mine on the right now falls outside Unesco’s buffer zone, but the game farm where prospecting is taking place is inside the buffer zone. A road to the Botswana border post at Pontdrift separates the game farm from Mapungubwe National Park

Vele sets the stage

Vele mine was given the green light after environmentalists and SANParks officials negotiated an offset agreement with the mining company as a condition to it obtaining a mining licence. The environmental damage caused by the mining was valued and penalised, and specialists were able to stipulate where mining was to take place and to protect areas that are either culturally or environmentally sensitive.

At its opening the Vele Colliery said it had 362,5-million mineable tonnes of shallow dip coal to be mined for 16 years, via a combination of opencast and underground mining. But after financial setbacks the Vele mine was placed under care and maintenance in October 2013 because it was not profitable to operate under current conditions.

Unesco’s World Heritage Committee has made it clear that mineral, oil and gas exploration or exploitation is incompatible with World Heritage status, Mechtild Rössler, director of the World Heritage Centre, told Oxpeckers.

Rössler said due to threats related to the management of the Mapungubwe site and development pressures, notably mining, the committee has kept an eye on the site over the years.

“Should a World Heritage Site face considerable threat to its values, the committee may decide to inscribe it on the List of World Heritage in Danger,” she said. “This was never the case for Mapungubwe Cultural Landscape.”

As part of this monitoring process, South Africa has to report to the committee on the state of conservation of the Mapungubwe site, Rössler said.

In 2014 the Unesco committee approved a new boundary and buffer zone for Mapungubwe in response to the past concerns regarding the impacts of mining on the site, Rössler said.

Despite South Africa adopting an environmental management framework and measures to control the processing of existing mining rights in 2016, Unesco continues to have concerns, she said.

In 2018 South Africa submitted a report in which it declared that Mapungubwe faced no threats from mining and that the two existing mines, Vele Colliery and Venetia mine, both located outside the revised buffer zone, had no significant impact.

Unesco replied that the report gave very limited information on the current state of conservation of Mapungubwe, including monitoring and conservation activities undertaken since 2016.

It asked South Africa to prepare an updated report to declare any major new proposals by December last year. The responsible department, DEFF, did not respond to questions on whether the updated report had been submitted.

Prospecting holes drilled on the game farm owned by Swedish businessman Leif Rahmqvist. Photo supplied

Confirmed prospecting

Leif Rahmqvist, a Swedish businessman, bought a number of farms in the area after 1994 and consolidated them to create a 25,000ha game farm along South Africa’s border with Botswana, near Pont Drift. He named the game farm Mapungubwe Game Reserve, though SANParks won a court case last year prohibiting Rahmqvist from using the name Mapungubwe after the judge ruled that using the same name may cause confusion.

“I wanted to create a space for free-roaming animals with no fences. I fell in love with South Africa, its animals and its people,” Rahmqvist said.

But then miners moved in and threatened his dream, he said. Prospecting has taken place on two of the properties that make up his game farm, which borders on Mapungubwe National Park.

IG Resources, a junior Indian mining company looking to expand its operations in South Africa, and Micawber 639, which holds the current prospecting licence, started prospecting on his farm six years ago. Rahmqvist said IG Resources paid “a lot of money” to Micawber to secure the prospecting rights.

According to the environmental management plan for the prospecting application, Rahmqvist did not oppose the licence. The Swedish national told Oxpeckers he was advised there was little he could do to stop mining.

“It is a South African law. Even as a landowner, I can’t stop it. I wanted to stop it. There was even some illegal prospecting on the farm that I shut down, but the legal prospecting I had to allow. IG Resources negotiated with me about access, and how it should be done,” he said.

“They found very good coal, it was high quality,” he confirmed. “But because of oil prices, to mine that coal is not economical right now. So it was stopped. A big problem on my farm is the infrastructure problem. They need to transport the coal, with a railway or road. They need bigger infrastructure.”

The proposed SEZ a few kilometres away could fix that problem, he said.

While land owners don’t own the mineral rights on their property, they are listed as an affected party and have to be compensated for any damages or activities on their farm. But a land owner’s consent increases a company’s chances of securing a mining licence.

“I don’t want it, I oppose it. But there is little I can do,” Rahmqvist said.

Farmers in the area accused Rahmqvist of facilitating the mining by signing a contract with IG Resources in which he gave his written consent for prospecting, and alleged that he and a charity he set up in Alldays would receive monies from the deal.

However, Rahmqvist denied he would profit in any way from the coal mining. Instead he told Oxpeckers that he would never sell his land, and that he didn’t want to go into an agreement with the miners.

“But it is difficult. I want to protect my land and the animals. But what can I do as a non-South African individual?” he said. “Ecotourism is a much better option for the area.”

Because the coal ridge is quite shallow on Rahmqvist’s farm, open cast mining will be the preferred mining activity, which is extremely detrimental to the environment.

Prospectors were satisfied that they had found sufficient coking coal on Rahmqvist’s farm and have now apparently applied for bulk prospecting licences, which is the first step to gaining a mining licence, said local resident Eugene Small.

Shezi, however, said the department could find no record of such an application by either Micawber or IG Resources.

Leif Rahmqvist with children at an orphanage he founded in northern Limpopo. Photo courtesy Rahmqvist Foundation Centre

Transfrontier park

The prospecting also threatens the proposed Greater Mapungubwe Transfrontier Conservation Area (TFCA), a major regional wildlife conservation and ecotourism initiative involving South Africa, Botswana and Zimbabwe where the three countries meet at the confluence of the Limpopo and Shashe rivers.

Small, a local farmer and hunter, said the transfrontier area has an abundance of elephants, already too numerous for its shrinking space. If coal mining is allowed, the elephants that migrate from Botswana’s Tuli area across the border into South Africa will be even more threatened.

Small said he had watched with trepidation as coal companies drilled prospecting holes and was dismayed when the results showed there was a rich seam with money to be made.

“This is a special part of South Africa, a true wilderness area that is unique. Once the first pit is dug, and the trucks move in, you can kiss the uniqueness and Mapungubwe’s charm goodbye,” he said.

Job creation in the area is critical, he said, but farming, hunting and ecoutourism can trump whatever mining has to offer.

Llewellyn Leonard, a professor of environmental science at the University of South Africa, and his research colleague Lebogang Thema warned that the mining threat would destroy tourism opportunities in the area.

Their research four years ago showed the Vele mine had employed approximately 826 permanent employees (short-term jobs) before being put into care and maintenance, while the tourism sector employed around 700 permanent employees (long-term jobs).

TFCA management estimated that a further 3,904 jobs could be created through tourism opportunities.

Though the governments of Botswana, Zimbabwe and South African signed an agreement on the transfrontier park more than a decade ago, little progress has been made since then.

Thakuli said before the TFCA can be established a memorandum of understanding has to be signed, although SANParks is operating within the framework of that agreement. “The only outstanding issue is the treaty, which is handled at the level of heads of state of the three countries,” he said.

He declined to comment on whether mining poses a threat to the TFCA, saying a proper and detailed assessment has to be made.

Rahmqvist’s game farm could potentially be part of the TFCA, said Thakuli, but it would have to abide by strict norms and conditions. Rahmqvist said he was negotiating about his property’s inclusion, but that it took time.

Number of licences

In 2016 Mapungubwe National Park manager Chrispen Chauke told researchers Leonard and Lebogang that 423 mining and prospecting applications had been submitted to the DMR in northern Limpopo. Of these eight were refused, 12 were rejected, 29 were withdrawn, 174 lapsed and 157 were accepted. Of those accepted, 43 were issued, Chauke said at the time.

The Limpopo regional office of the Department of Mineral Resources closed doors for two months in 2018 following allegations of corruption and intimidation, Engineering News reported. The office opened again at the end of that year, but the office administration remains poor and Oxpeckers was not able to access or verify any permits issued by the office, nor were questions addressed to the office answered.

Asked how many prospecting and mining licences had been granted in the area, national DMR spokesperson Shezi responded that 23 prospecting licences had been issued.

Shezi was adamant that DMR is aware of the sensitivity of Mapungubwe National Park. “The department is currently undertaking a process of restricting mining-related activities in and around the park,” she said.

The prospecting is taking place in one of South Africa’s most water-stressed regions. Photo: Yolandi Groenewald

Water worries

Although the area is not an identified and protected freshwater priority zone, it receives an average annual rainfall of less than 400mm and the Limpopo river ceases to flow during the dry season. No new water rights are currently available, but some farmers in the area may be willing to sell their water rights to mines, local sources said.

Preliminary studies to identify water sources for the Musina-Makhado SEZ, conducted by the Department of Water and Sanitation, identified possible sources that are not being used in Zimbabwe. According to a #MineAlert investigation in August 2019, “Where’s the water for Limpopo’s industrial juggernaut?”, the SEZ is considering entering into an international water user agreement with the Zimbabwe National Water Authority for cross-border water transfer.

The same water sources could also be options for any new mines in the Mapungubwe area, local sources said. Vele mine only managed to secure a limited water use licence.

The environmental management plan that Micawber drew up back in 2008, when it was first granted a prospecting right, brushes over the environmental sensitivity of the wilderness area, and does not list the vast amounts of elephants that call the area their home.

Because prospecting licences do not require a water use licence, the environmental management plan did not touch upon the issue. However, Shezi said some bulk prospecting licences might require a water use licence if the activity warrants water usage.

This investigation is part of the Mining your Water series, supported by the Open Society Foundation for South Africa.

Use the #MineAlert app to keep track of water licence and mining applications in the region