09 Dec Cyber sleuths crack down on online wildlife crime

Law enforcement agencies in Europe are making an impact on illegal wildlife e-commerce, a #WildEye data investigation shows

Reptiles are among the most popular species advertised online. Green tree snakes (CITES Appendix II) are just one of the many species for sale on platforms such as Facebook and Instagram. Photo: supplied

Attempts to clamp down on online illegal wildlife trade have been boosted by more than a dozen recent interventions by law enforcement agencies in Europe, data collated by #WildEye shows. The majority of these interventions resulted in convictions and arrests in cases involving several hundred thousand euros.

The cases include the sentencing in the United Kingdom of Catherine Emberton to 120 hours of community service in 2015 for selling more than 100 pieces of jewellery containing tiger parts. Her business made close to €21,000 in total.

Police discovered she was selling the jewellery on an internet auction site. Emberton tried to pass the pieces off as antiques, which would make them exempt from requiring permits. However, the items did not qualify for exemption and most of them contained raw teeth and claws set in metal.

In 2016 antiques expert Chao Xi received a six-month prison term from the Portsmouth Magistrates’ Court in the UK, suspended for two years, for illegally trading more than €10,600 worth of ivory on eBay, which he had bought as “trinkets” for his family.

Last year 40-year-old Timothy Norris, also from the UK, was caught selling fur coats, scarves and hats made from endangered leopards and wolves on eBay. Items seized from his home were determined to have been made from animals that had been killed recently, and included clothing made from snow leopards, clouded leopards, lynxes and wolves, all of which are classified as vulnerable or endangered species.

Also in 2018 a rhino horn was seized in France after its owner put it up for sale online for €200,000. Authorities investigated the man, whose name remains unknown publicly, for almost a year before conducting a search of his home.

At the beginning of 2019, more than 200 illegally stuffed animals were seized by police in Spain after they discovered online posts advertising the animals for sale. Six people were arrested and law enforcement agents found dozens of stuffed animals, including an African lion, white rhino, Bengal tiger, hippopotamus, African crocodile, antelope and giraffe, in an illegal taxidermy workshop in Alicante.

More than 200 stuffed endangered animals were seized from an illegal taxidermy workshop in Spain in February 2019. Photo: Spanish Civil Guard

Global trade

The incident in Spain was one of the more significant online-related seizures, due to its size and scale. Though the money earned illegally in these crimes is substantial in some cases, however, none of the incidents involved large-scale organised criminal networks.

And despite the successes in curbing online illegal wildlife trade, #WildEye data shows that it continues to thrive. It is part of a global illicit wildlife trade estimated to be worth between $7-billion and $23-billion each year, according to the World Economic Forum, though it is impossible to know the true value of online wildlife trafficking.

Increased access to online technologies and e-commerce platforms – as well as the rapid rise of social media – have provided new channels for criminals to operate through and, according to wildlife trade monitoring network TRAFFIC, “illegal wildlife trade has become a common occurrence online”.

In response a global partnership known as the Coalition to End Wildlife Trafficking Online was launched in March 2018. It has just over a year to reach its stated goal of reducing wildlife trafficking online by 80% by the end of 2020.

The coalition, currently made up of more than 30 partners, is led by the World Wildlife Fund, TRAFFIC and the International Fund for Animal Welfare. All the organisations involved agreed to a multifaceted approach to shut down online trade routes for cyber criminals, acknowledging there is no one solution to the problem.

Since its establishment, the coalition has actively assisted law enforcement agencies, explored new technology to detect and eliminate illegal trade information, and has raised awareness among platform users, according to TRAFFIC’s executive director, Steven Broad. He touched on the group’s activities and achievements at a gathering in Beijing in March. An additional eight internet companies joined the coalition and several publications and campaign ideas were introduced.

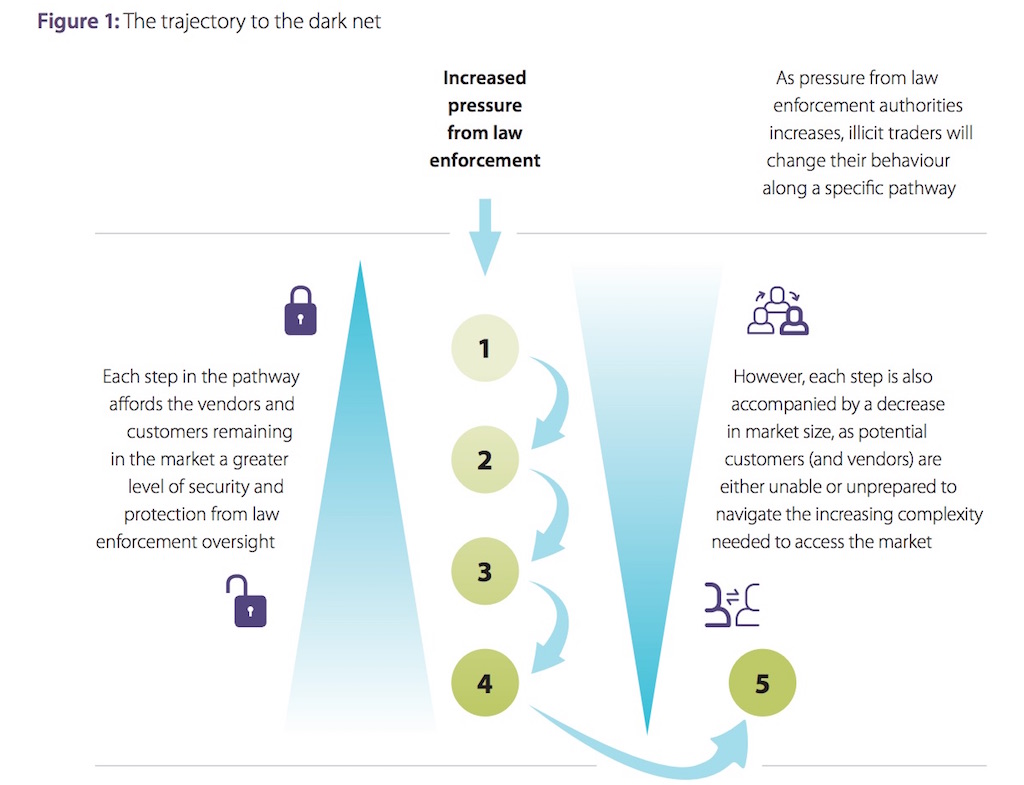

Increased law enforcement could lead illicit traders to the dark net over time. Graphic: Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime

Dark Web

Research and analysis by the Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime suggests very few criminals turn to the Dark Web to trade in illegal wildlife because the use of closed groups and private chats on social media enable the trade so there is no need to look elsewhere for the time being. This could start to change as law enforcement “steps up” and the trade is forced to evolve into something less conspicuous, the organisation says.

Investigations by the Alliance to Counter Crime Online (ACCO) have shown how the very technologies meant to moderate harmful content on the internet actually connect traffickers faster than moderators can remove them, according to wildlife trade investigator Dan Stiles.

ACCO’s work in trying to detect and disrupt wildlife crime online focuses mainly on Facebook and Instagram, and they have publicly condemned these companies for failing to act appropriately when they see wildlife trafficking take place on their platforms.

While individuals selling illegal commodities online can be prosecuted, Stiles wrote in a commentary piece in October this year, there are not yet any legal pathways in the United States that formalise and regulate cooperation between online service providers and law enforcement agencies. The main problem is these platforms’ privacy policies and regulations.

“When it comes to social media, the enabler always walks free,” said Stiles. “It’s time for regulators to take steps to hold online platforms accountable for facilitating the illegal trafficking of wildlife.”

ACCO collects data of online posts advertising illegal wildlife for sale and passes them on to law enforcement to investigate. Together with other member organisations, they have gathered comprehensive information about how and where criminals operate, and recommendations for what internet companies and law enforcement should do to disrupt wildlife crime.

Research by IFAW in 2017 found reptiles, birds and ivory are the most commonly traded species online. Graphic: Roxanne Joseph

Legal vs illegal

Ivory and reptiles are two of the most popular commodities for sale online. In 2017 IFAW recorded more than 12,000 endangered and threatened specimens offered for sale over a period of six weeks, via nearly 6,000 advertisements and posts on online marketplaces and social media platforms. Reptiles made up the largest group of animals for sale, including mainly live tortoises and turtles.

Online criminals target the remaining markets where ivory can still be sold legally as antiques. On auction sites, including eBay.uk, dozens of items made from ivory are offered for sale.

A recent study by the University of Kent found these online ivory traders are exploiting the complicated set of rules created to restrict the trade in the UK to antique items made prior to 1947. The traders claim their items are antiques, but many of the ivory products for sale on marketplaces like eBay are in fact items fashioned from poached elephant tusks.

Currently the only reliable method of determining the age of ivory – carbon dating – is an expensive and lengthy process. The online-based ivory trade highlights the difficulty in distinguishing between legal and illegal products.

Determining the legality of trade is also a problem in reptile trade online, where traders often produce counterfeit documentation. Exotic-looking reptiles, such as iguanas and the southern African giant girdled-lizard (Sungazer), are often traded through Europe, where the continent acts as a stop-over point.

Southern Africa is rich in reptile diversity, comprising almost 500 species and, according to Michael Adams, a herpetologist at the Biodiversity Company, most of the reptiles are only found nowhere else in the world. This makes them a target for the illegal pet trade.

At the same time, many endangered reptiles originating from Southern Africa are threatened and endangered, but are not protected by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) and are therefore not protected under European Union laws.

After traders smuggle the reptiles to Europe, they are mostly free to trade across borders within the EU and demand high prices without the fear of penalties.

At the Terraristika reptile trade fair in Hamm, Germany, it is difficult to tell if the deals are legal or not. Prices range from €75 for a chameleon to more than €2,000 for a boa snake. Many of the species on sale there are protected by CITES and yet thousands of euros change hands.

Every seller has a website to show off their merchandise and lots of interactions take place online, prior to the fair. According to Italian journalist Rudi Bressa, who attended the fair earlier this year, “Traders here know each other and they communicate via social networks.”

This article by the Oxpeckers’ #WildEye manager was supported by a grant from the Earth Journalism Network’s Investigating Wildlife Trafficking project