13 Nov ‘Greatest wildlife crime on the planet’ threatens multiple ecosystems

Millions of glass eels are smuggled out of Europe each year, and their looming extinction poses a serious ecological threat. #WildEye looks at the impact their decline has on other species

European eels are most vulnerable at an early stage of their life cycle, when they are small, transparent glass eels around 7cm long. Photo: Sustainable Eel Group

Smuggling of glass eels – juvenile eels, also known as elvers – from Europe to Asia has reduced the population to less than 10% of what it was three decades ago. In some areas they are already starting to disappear entirely, according to Laurent Beaulaton of the French Agency for Biodiversity.

The Sustainable Eel Group has dubbed this trade the “greatest wildlife crime on the planet”, and estimates it to be worth about $5-billion a year. Earlier this year the group’s Andrew Kerr said when the eels leave Europe they are worth one Euro each and within a year, having grown in size on an eel farm in Asia, their worth jumps to 10 Euros.

Despite being listed as critically endangered by international conservation bodies, and the suspension of their export out of and import into Europe since 2010, the smuggling of European eels to Asian destinations has rocketed since the 1980s.

According to the Sustainable Eel Group, more than 75% of the juvenile eels being trafficked come from France, and to a lesser extent, Spain, Portugal and the United Kingdom.

The group’s director of scientific operations, Florian Stein, says the illegal trade is a major threat to the species’ survival, alongside overfishing and habitat loss.

The decline of the species is a significant problem for Europe, because they have socio-economic importance and have historically sustained many small-scale fisheries. They are also at the epicentre of many of the ecosystems in which they exist.

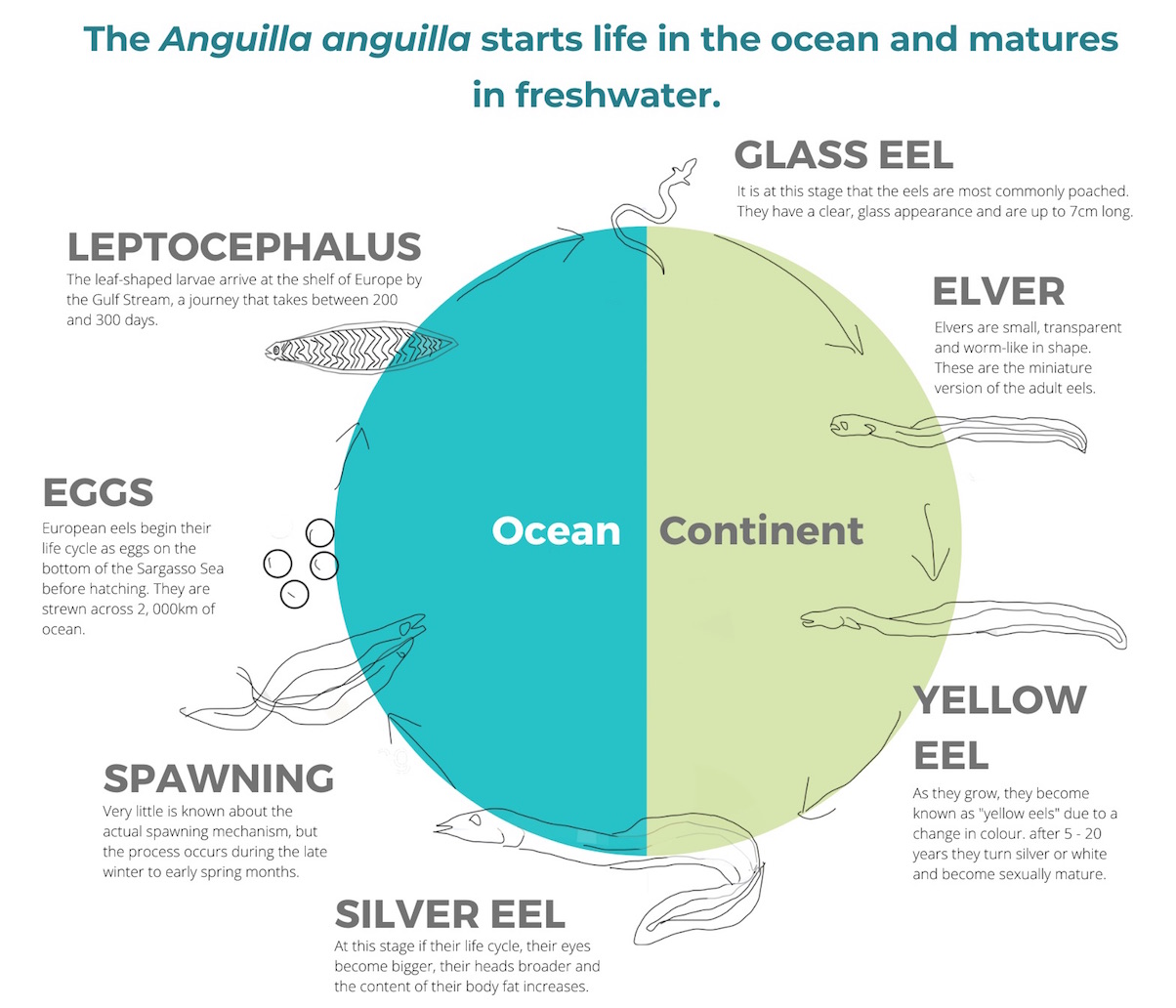

At all stages of their life cycle, eels are central to a range of ecosystems. Graphic: #WildEye

Life cycle

Eels begin their life cycle in the ocean and spend most of their lives in fresh inland or brackish coastal water, returning to the ocean to spawn and die. The leaf-shaped larvae are brought to the continental shelf of Europe by the Gulf Stream, a journey that takes from 200 to 300 days to complete.

Upon approaching the coast, the larvae metamorphose into a transparent “glass eel” of up to 7cm long, enter estuaries and many migrate upstream. It is at this stage that they are most commonly poached, often to be consumed as appetisers in restaurants in south east Asia and around Europe.

As they grow, they become known as “yellow eels” due to a change in colour and after between five and 20 years they turn silver or white and become sexually mature. They are usually around 60-80cm long and can, in exceptional cases, reach a length of up to 1,5m.

At this stage in their life cycle, their eyes become bigger, their heads broader and the content of their body fat increases. This makes them a meaty feast for other, larger carnivores.

Because they range in size throughout their life cycle, the carnivorous European eels are an important and formerly abundant food source in all of the ecosystems in which they exist. Their diets primarily consist of invertebrates, such as molluscs and crustaceans, and other fish.

Small and top predators alike consume the eels, especially during colder months, when the eels are particularly vulnerable because this is when they hibernate and do not feed.

Eels are central to a range of ecosystems, said Beaulaton: “There are not many species in European rivers, so if even one species is erased – and the eel is usually the most abundant – this can have a big impact on the ecosystem.”

European eels, at any stage of their life cycle, are important to maintaining a balanced ecology as they play a significant role in the food chain, Beaulaton said. Otters and birds such as bitterns and herons often prefer eels to salmon because they are a lot easier to catch and have a high fat content.

In spring, when many species are reproducing, elvers become an even more important food source for predators needing to keep their energy up. Eel declines put extra pressure on salmon populations, which end up being the major food source for the predators.

Eels also have cultural significance in many European countries, and are the basis of popular dishes in many restaurants across the continent.

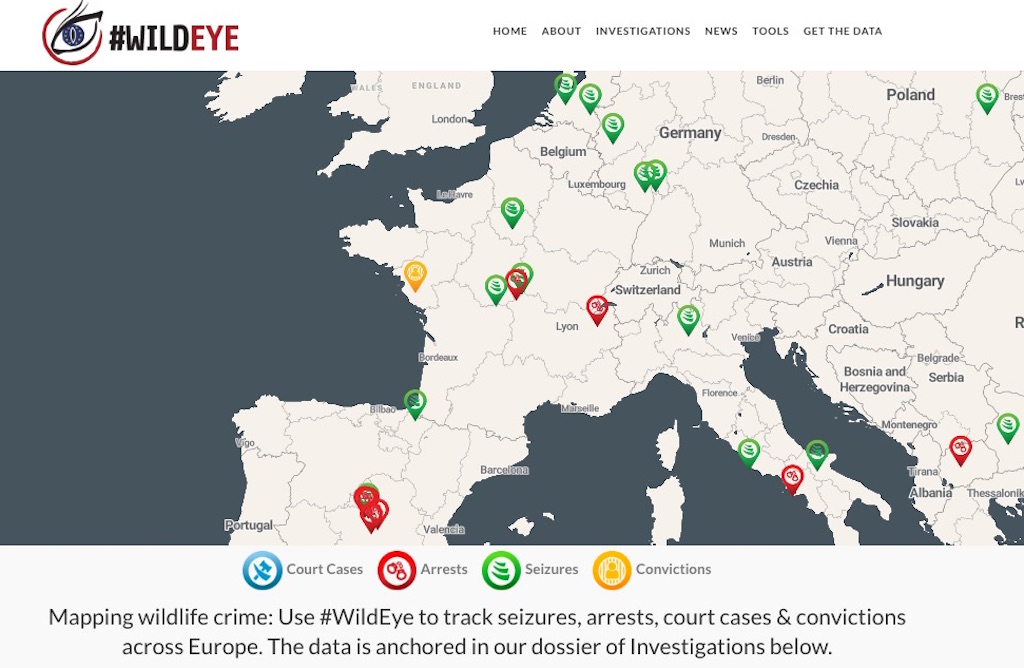

Oxpeckers’ #WildEye tool includes more than two dozen incidents related to European eel smuggling in the past five years. Photo: Supplied

#WildEye data

A search of data on eels on the Oxpeckers’ mapping tool #WildEye shows there have been more than 20 significant European eel-related law enforcement incidents (excluding large-scale operations) in Europe over the past five years. Almost a third of these are arrests and convictions.

In 2015, for example, 100kg of eels were seized from fish markets in Bari, Italy. They were poached from Lake Lesina, a well-known haven for the species due to its abundance of food sources. That same year, two Chinese traffickers were arrested after two million glass eels – which they declared as a “food product” and transported in polystyrene boxes – were seized at Sofia Airport in Bulgaria.

This year in April, five men were arrested for trying to smuggle nearly €120,000 worth of eels from Macedonia to Malaysia. Authorities discovered the live cargo (glass eels) hidden in a car in which four of the traffickers were travelling, during a routine highway control check. A customs official was accused of granting them a “free pass” from Bulgaria into North Macedonia.

At the end of October two Chinese nationals were sentenced in France for trying to smuggle baby eels in their suitcases. The court in Bobigny handed down a 10-month suspended sentence and €7,000 fine each.

Operation Lake, a joint investigation launched in 2016 by Europol, Eurojust, Interpol and the European Union Wildlife/CITES Enforcement Group, saw nearly 500 separate operations taking place across the continent in 2018/9. Glass eels were one of the endangered species targeted.

In early November 2019 Europol announced that more than five tonnes of glass eels were smuggled during the most recent fishing season this year. More than 150 suspected smugglers were arrested and all the eels seized were reintroduced into their natural habitat.

Operation Fame resulted in 38 arrests and more than 700kg of glass eels recovered. The confiscated eels had been placed in plastic bags and suitcases, to be sent to Asia by plane. Spanish newspaper Euro Weekly reported that 16 arrests were made and four criminal networks dismantled, all at the centre of a €6-million eel smuggling ring. In this instance, almost six tonnes of live glass eels were seized and subsequently returned.

Both operations form part of the European Union’s recent efforts to curb the extinction of some of the continent’s most endangered species, including glass eels.

In an effort to curb the smuggling, methods to trace the eels’ DNA are being developed. While the science is not yet 100% accurate, genetic evidence is as close a match as possible.

The aim is to be able to identify eels coming in or going out of Europe. Currently scientists are able to distinguish between eels living in different habitats, under different conditions, using muscle tissue and certain elements of the eels’ DNA. In the most recent substantial study, they were able to tell the difference between eels from the United Kingdom, France and Spain.

Farmed eels being fed with a pendulum feeder. Photo: Scandanavian Eel Group

Eel farms

One place where this technology could be useful is on eel farms. While eel farming in Europe is not illegal, exporting the fish to other countries is. However, there are few farms in Europe, according to the Federation of European Aquaculture Producers, and they produce a total of about 6,000 tonnes of eels each year.

Glass eels are captured mainly along the shores of Europe with nets, trawls or traps. In many instances, they are sent to eel farmers where initially, they are kept in smaller tanks for quarantine purposes. Here, farmers examine the eels for disease and wean them on to artificial diets.

As they grow heavier, they are transferred to a juvenile production unit with larger tanks. When the eels reach marketable size, they are moved into larger ponds, where the temperature and their diets (now several meals of dry feed a day) are carefully monitored.

This is only one farming technique, though. They are also cultured according to a system known as valliculture, where they are grown in marine and brackish waters.

After harvesting, the eels are sorted into different sizes and kept in holding tanks without food for one to two days to prevent any possible off-tastes. If they are intended to be eaten fresh, they are chilled, packed into oxygenated plastic bags with a bit of water to maintain moisture, and then transported to markets and restaurants.

This article by the Oxpeckers’ #WildEye manager was supported by a grant from the Earth Journalism Network’s Investigating Wildlife Trafficking project