25 Oct Where’s the water for Limpopo’s industrial juggernaut?

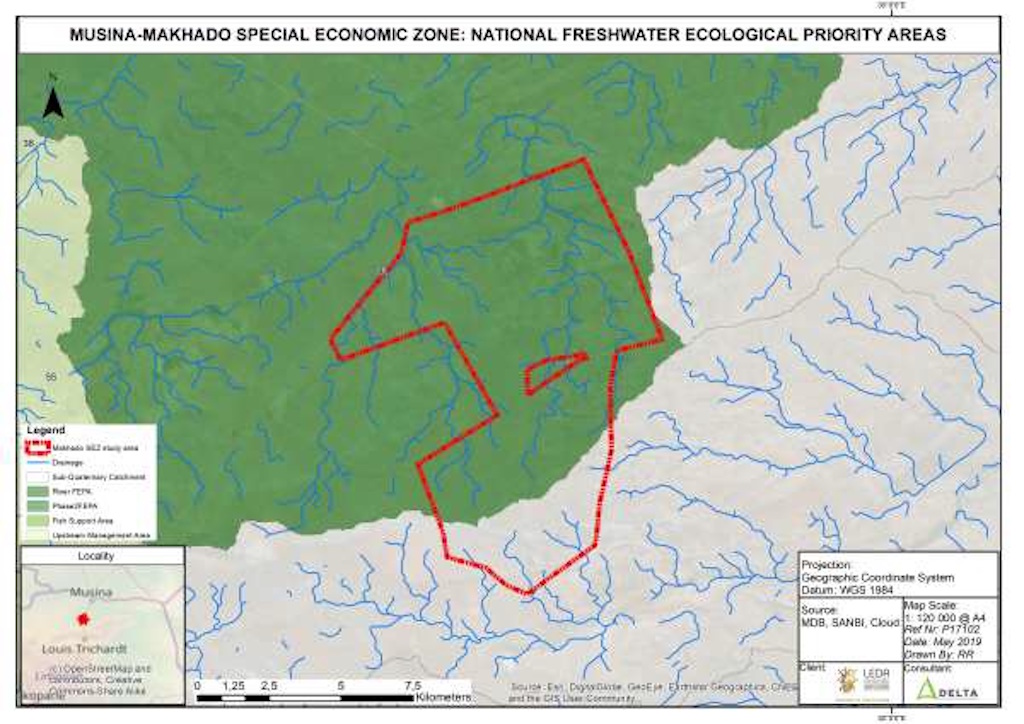

Limpopo’s flagship Musina-Makhado project is being developed in an arid region that includes national priority freshwater ecosystems. Andiswa Matikinca investigates

Shape of the future: A ‘typical illustration’ of what the Musina-Makhado SEZ could look like, according to the recently released final environmental scoping assessment report

The long-term availability of water is a critical risk for the development of a giant energy and extractives complex projected to rake in multibillion-rand investments in water-stressed northern Limpopo.

Chairperson of the Musina-Makhado Special Economic Zone (SEZ) board, Rob Tooley, said the availability of water is a big challenge for the development. Although he believes there are sufficient water sources to kickstart the project, he said it needs to ensure there is enough water to sustain it going forward.

Tooley said a specialist has been appointed to identify long-term water sources. Preliminary studies conducted by the Department of Water and Sanitation had identified water sources that are currently not in use in Zimbabwe and the project would likely enter into an international water user agreement with the Zimbabwe National Water Authority for cross-border water transfer, he said.

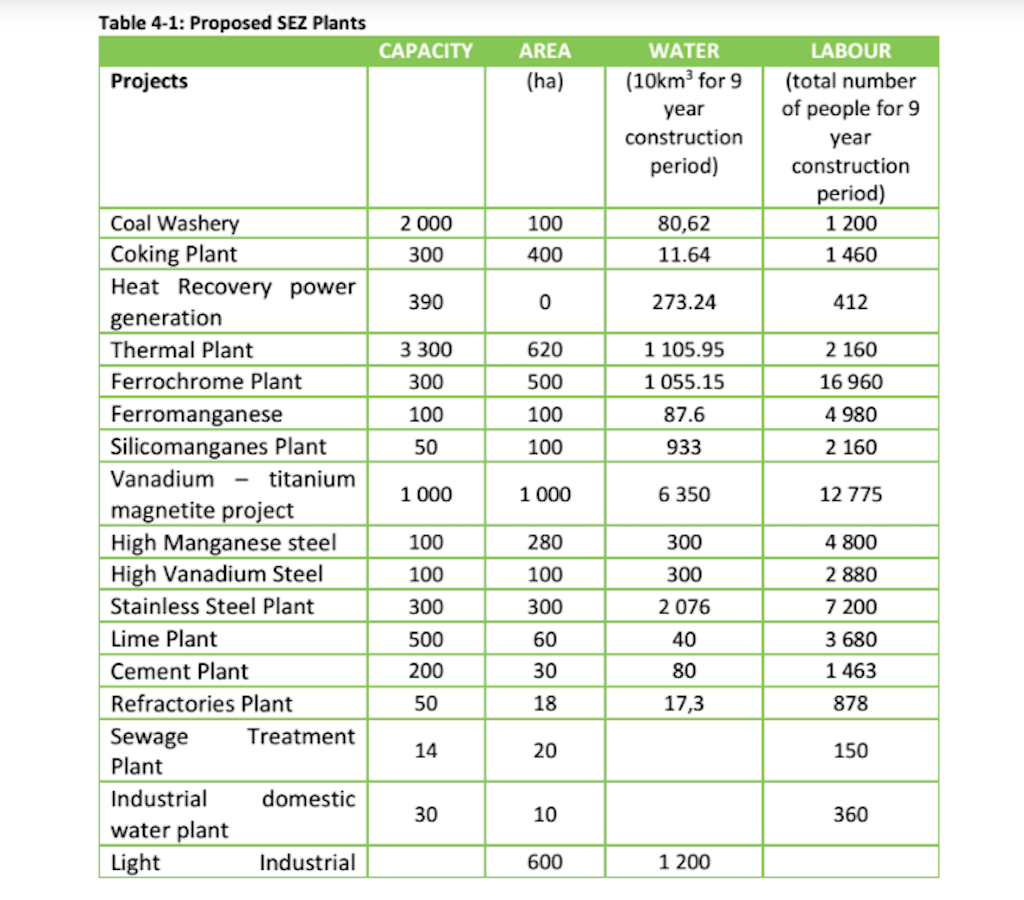

A Government Gazette notice published in September 2016 noted that total permissible surface and groundwater abstraction volumes available for the SEZ project were estimated to be 0.377 cubic metres. However, according to the recently released final environmental scoping assessment report, the first phase of the development alone will require a total of 123-million cubic metres of water, 30-million of which is expected to be provided by the Limpopo Department of Water Affairs.

“The project would be built in an area of Limpopo that is already so water-stressed that the Department of Water and Sanitation, and the final scoping report itself, concede that a ‘definite source of sustainable water for the SEZ is still under investigation’,” said Ruchir Naidoo, an attorney at the Centre for Environmental Rights.

“It is clear that without a guaranteed supply of water, the SEZ would not be able to function, nor would it be able to contribute towards long-term regional ‘development’ goals without having severe consequences for other water-users and ecosystems. This could have country-wide repercussions, particularly if water resources from other parts of the country are to be relied on.”

Overlap: A large section of the 7,000ha southern development site occurs within national freshwater ecological priority areas. Map from environmental scoping assessment report

Freshwater priority areas

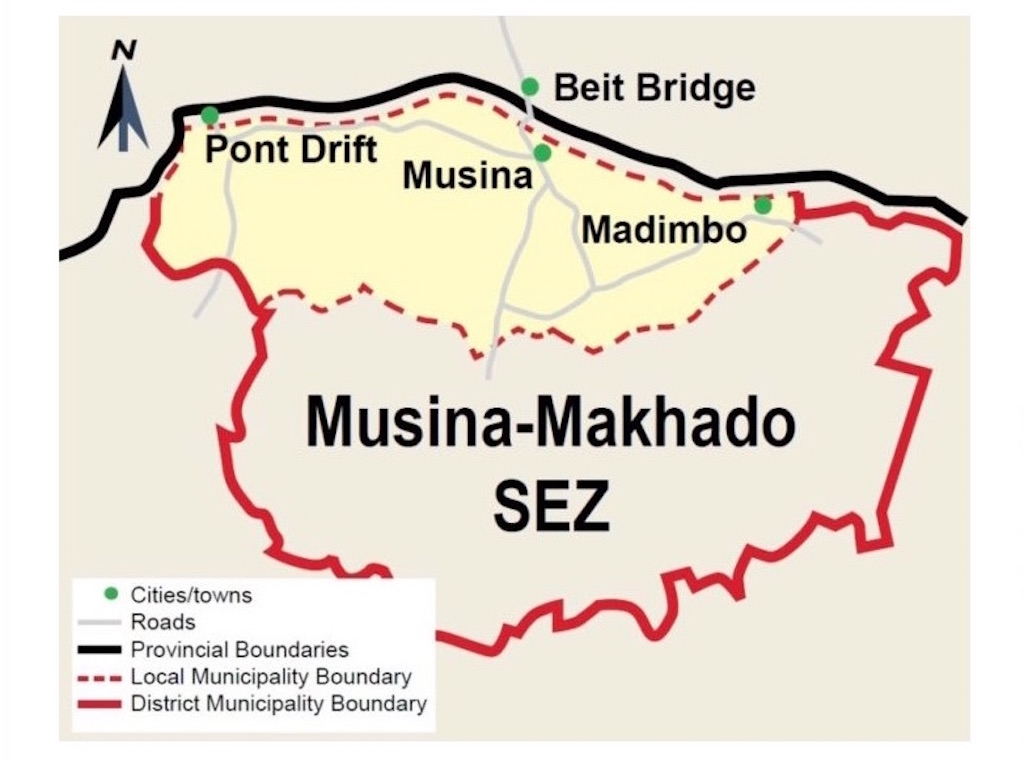

Designated by the Department of Trade and Industry in 2016 and gazetted in 2017, the Musina-Makhado SEZ development is part of a deal struck by President Cyril Ramaphosa and his Chinese counterpart, Xi Jinpin, in which the Bank of China will pump at least R15-billion into SEZs in South Africa, Mail & Guardian reported in March.

Concerns about the Musina-Makhado development include potential impacts on water catchments in the Limpopo and Sand water management areas. A large part of the development falls within an identified National Freshwater Ecosystems Priority Area (NFEPA), according to the scoping assessment.

The two main sources of water in the region are the Limpopo river, the second-largest perennial river in South Africa, and the Nzhelele Dam. This is a catchment area that is also characterised by wetlands, eight of which fall within the project’s southern development zone.

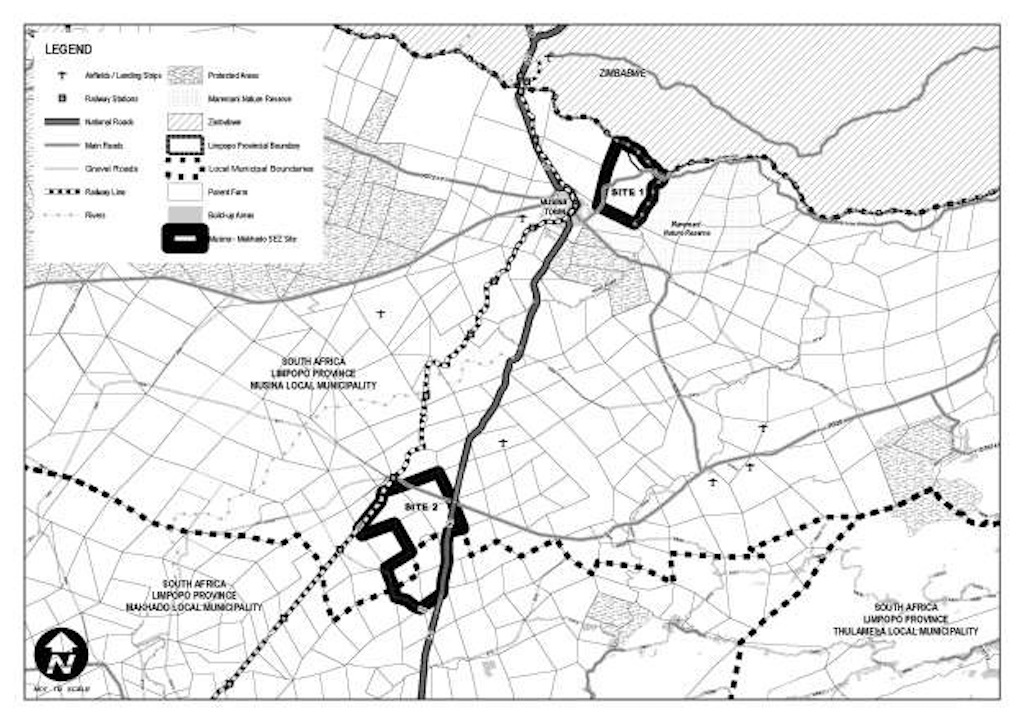

The SEZ consists of two main sites: the northern site is designated for small industry development and the southern site is anticipated to become a heavy industrial hub specialising in energy and metallurgical development.

The southern site, which falls between the Musina and Makhado local municipalities and covers more than 7,000ha, has raked in investment commitments of more than R150-billion and could create more than 21,000 jobs, according to the province’s premier, Stanley Mathabatha, in his state of the province address in March.

In addition to the energy and metallurgical complex for the production of high-grade steel, the SEZ will host other land use activities that include infrastructure, light industries, intermodal facilities, housing, retail centres, business uses, community facilities and telecommunication services, according to the final environmental scoping assessment report.

Rich pickings: The area marked for development has large deposits of coal and various metals. Map courtesy LEDA

Environmental impact assessment

The SEZ is now in the process of conducting its Environmental impact assessment (EIA), which according to the National Environmental Management Amendment Act must include public engagement on the potential positive and negative environmental impacts of the proposed development.

Mining contributes at least 24% of Limpopo’s income and is expected to be boosted by the SEZ development. Adjacent to the SEZ site, MC Mining (Coal of Africa) currently holds four mining right applications for hard coking and thermal coal. There are also 11 applications for prospecting, exploration and mining rights for coal, copper, ore, sand and a range of heavy minerals on the eight farms where the Musina-Makhado site is located – two were rejected while the others have been granted.

Tooley confirmed there are prospective mining projects in the area as it has large deposits of coal and various metals. “In conjunction with the Department of Mineral Resources and Energy, we are investigating who has licences, who will be extracting what and what we will have to do prior to anything happening and signing off on those agreements,” he said.

The northern development zone (site 1) is designated for small industry development, the southern zone (site 2) is anticipated to become a heavy industrial hub specialising in energy and metallurgical development. Map from environmental scoping assessment report

Concerns and objections

The final environmental scoping assessment report, which outlines the major potential impacts to be addressed in the EIA, notes that the environmental concerns in Limpopo align with those applicable to the rest of South Africa and that these will require “further detailed investigation”.

These concerns include “intrusion into the protected area network, detrimental effect on the biodiversity assets of the region, resource use conflicts (especially with respect to land and water), large-scale land transformation, potential increase in pollution pathways and high water requirements of the development in a water-scarce area where much of the existing water resources are required for agriculture and thus food security”.

Tooley said the project has met some negativity from farmers and communities involved in agricultural activities, but will continue to negotiate and engage with them. The possibility of the construction of a coal-fired thermal plant has also been met with negativity, but he believes this might not be built because concerns around global warming.

Mashile Phalane, head of the community-based Batlhabine Foundation in Limpopo, voiced his concern about the number of coal-mining applications which he believes are on the rise due to the mining prospects mentioned in the SEZ project. His biggest concern is the effects of mining on scarce water sources in the area, leading to impacts such as acid mine drainage that could affect agriculture, a major contributor to the province’s economy.

Phalane said he was also concerned about Chinese investments into the SEZ, which he believes will be “a way of pocketing money”, and about the protection of human rights when development starts.

Some of the manufacturing plants envisaged for the heavy industrial development zone in the southern site, according to the environmental scoping assessment report

New power station

Civil organisations grouped under the Life After Coal/Impilo Ngaphandle Kwamalahle campaign are opposing the development of new fire-powered coal stations and associated mines in the SEZ. This includes a 3,300MW thermal power plant that will cover an area of 620ha and run on fossil fuels, according to the scoping report.

Speaking on behalf of one of the organisations, groundWork, Bobby Peek said proceeding with this type of project doesn’t make sense considering the costs of coal-fired power stations, climate change and the costs to human life and the environment.

“We can’t afford to continue with the very same industrial development model that has created the poverty and environmental injustices we have today. We should be looking for a new development model, we can’t continue relying on mining, which has destroyed our water and our people’s health. We can’t rely on smelting, which has caused millions of tons of toxic pollution around the country,” said Peek.

The Centre for Environmental Rights is representing a civic coalition that plans to object to the EIA on a range of issues, including potential water, air quality and climate impacts.

The centre submitted a request under the Promotion of Access to Information Act to the Department of Trade and Industry earlier this year, asking for various documents containing economic, technical and legal information on the SEZ project. It received partial electronic access to some of the documents requested, and the items that were refused were on the basis of them being non-existent or outside of the DTI’s possession, Naidoo said.

“It is clear that the anticipated environmental, climate and health impacts of all of these facilities combined will be astronomical. With such impacts in mind, this becomes a matter of national and international concern,” attorney Naidoo said.

The environmental scoping report states that preliminary studies by the Department of Water and Sanitation found there were “unused water sources” in Zimbabwe that could be made available for the SEZ development. Questions sent to the department by Oxpeckers about which water sources had been identified and whether discussions for this arrangement with Zimbabwe had begun were unanswered.

Questions to the department about the status of water use licence applications for the SEZ development and for associated mining projects, and whether the potential impacts of these activities on the freshwater priority areas had been assessed, also remained unanswered.

Questions sent to the Limpopo Economic Development Agency about the impacts on water sources and how these will be mitigated were also not answered at the time of publication.

This investigation is part of the Mining your Water series, supported by the Open Society Foundation for South Africa. Use the #MineAlert app to keep track of water licence and mining applications in the region