21 Aug Status of plans to frack SA’s ‘water tower’

An Appeal Court ruling has stalled plans to frack the Drakensberg in KwaZulu-Natal, but two exploration applications are still on track. Yuexuan Chen investigates

Bird’s-eye view: Spioenkop Dam photographed from Sentinel Peak in Royal Natal National Park. The dam borders on exploration rights application 12/3/346. Photo: Yuexuan Chen

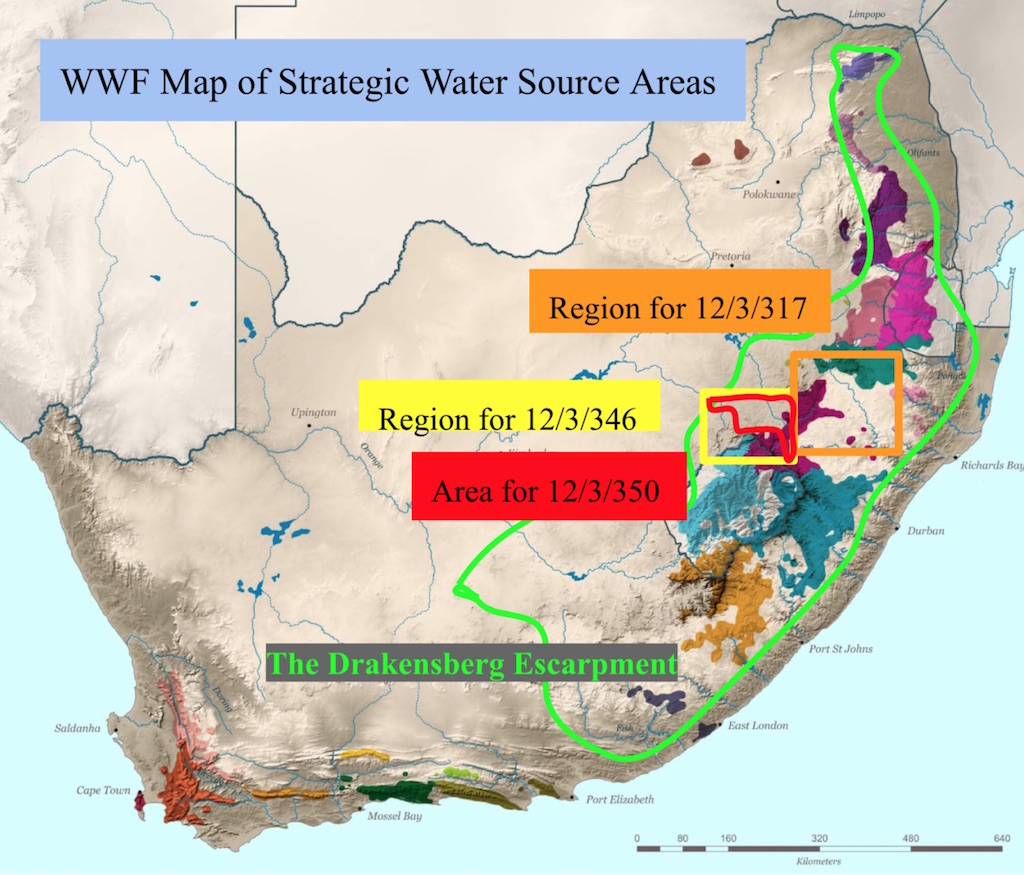

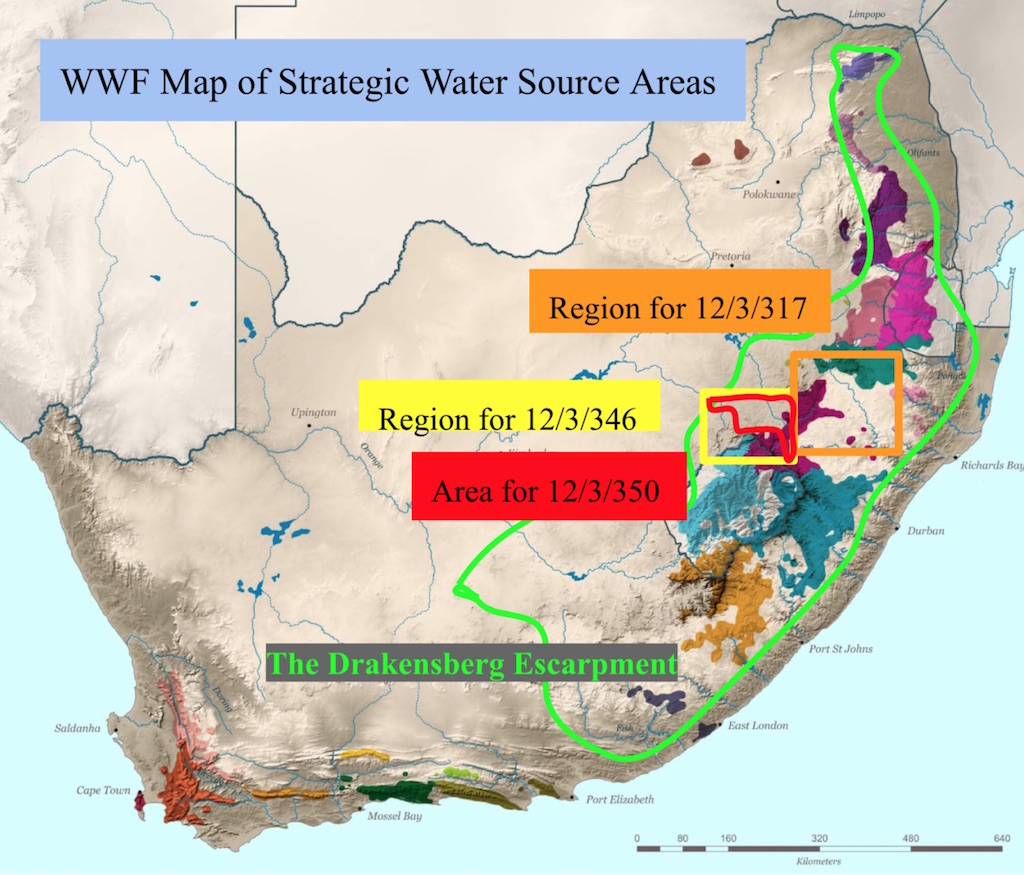

This year has seen a long fight in and out of the courts on the future of hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking”, in South Africa. A Supreme Court of Appeals ruling in July stalled fracking exploration in the Karoo, and one of the fracking exploration applications in KwaZulu-Natal was withdrawn.

Rhino Oil & Gas, the American company that registered exploration rights across large swathes of the Drakensberg escarpment, withdrew one of its applications (12/3/317 ER) – but it still has two more exploration rights applications that have been approved by Petroleum Agency South Africa (PASA).

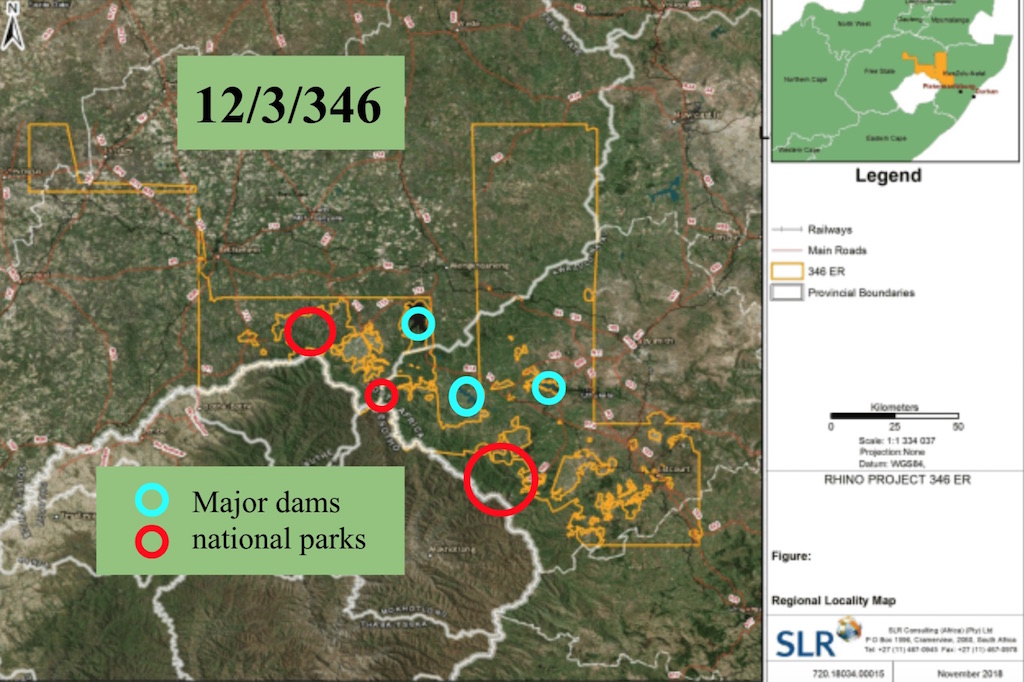

The first, application 12/3/350 ER, covers more than 7,000 square kilometres and 4,000 farms. The second, application 12/3/346 ER, covers more than 1,0000 square kilometres and 5,000 farms.

The survey areas of the second application border on three major dams – Woodstock, Sterkfontein and Spioenkop – and three national parks – the Royal Natal, Golden Gate Highlands and Maloti-Drakensberg national parks.

Under threat: The survey area for application 12/3/346 ER covers more than 1,0000 square kilometres and 5,000 farms. It borders three major dams and three national parks. Graphic: Yuexuan Chen

What does the court ruling mean?

The Appeal Court ruled on July 4 that the Department of Environmental Affairs has the power to regulate petroleum regulations related to environmental matters, not the Department of Mineral Resources. This case dealt with fracking exploration in the Karoo, but sets the precedent, according to PASA, for future shale gas legislation in South Africa.

“The Department of Mineral Resources understands that the ruling held that the exploration for petroleum by fracking should not take place before such time that it is lawfully regulated,” Lindiwe Mekwe, the chief executive of PASA, wrote in response to email questions.

Environmentalist Judy Bell from Frackfree SA believes “the ruling just slows [the oil companies] down”, and that the Department of Environmental Affairs will allow fracking to proceed.

“We haven’t even scratched the surface of environmental and social issues,” said Nicky McLeod, director of Environmental and Rural Solutions – a non-profit focused on sustainable development of rural communities. “Right now, we’re just fighting out the legal details in court.”

Other court cases brought by affected farmers against exploration applications that covered almost half of KwaZulu-Natal lead Rhino Oil & Gas to withdrawing application 12/3/317ER.

Janse Rabie, head of natural resources at AgriSA – an NGO that represents thousands of farmers – said the departments of environment and of mineral resources will need to redraft technical regulations before any fracking takes place, “and no invasive activities can take place until then. According to reports, it’s not even sure that there are sufficient shale gas reserves and a lot of evidence shows that the reserves are not viable.”

Water tower: Rhino Oil & Gas withdrew application 12/3/317 ER – but it still has two more exploration rights applications situated in strategic water source areas. Graphic: Yuexuan Chen

Impacts of fracking the Berg

Fracking injects high-pressure water and chemical mixtures into the ground to force oil and gas out of shale rock. Citing health and environmental concerns, four European Union countries, four provinces in Canada and multiple states and cities around the United States have banned fracking.

A ban on fracking in South Africa was lifted in 2012, with the government citing benefits of jobs and domestic energy production.

Rhino Oil & Gas is an American company based in Dallas, Texas. The US has recorded increases in agricultural water prices, water contamination in five states, decreased health of children living near fracking sites and earthquakes triggered as a result of fracking.

A huge area of the Drakensberg mountains lies within KwaZulu-Natal. “It’s the water tower of South Africa,” said Roland Schulze, emeritus professor of hydrology at the University of KwaZulu-Natal. “It’s a region with high rainfall and low variability of rainfall.

“It is not only a mountain range in which water flows eastward to the KwaZulu-Natal system that supplies the major dams, but also westward from Lesotho into South Africa’s biggest, most important dams. Pipelines from Lesotho supply the industrial hub of South Africa, Johannesburg.”

KwaZulu-Natal itself does not transfer as much water as it used to outside the province because of the dams in Lesotho. Water is the biggest export and main source of income for Lesotho – making up 40% of the country’s GDP, Schulze said.

Bronwyn Howard from Frackfree SA said, “KwaZulu-Natal is a water powerhouse. There are six major catchment areas in northern KwaZulu-Natal that feed through to major cities.”

Howard said the Tugela catchment, the most over-extracted in the province, would be affected if fracking goes ahead in the exploration areas.

One common argument in favour of fracking is that it could help create a domestic energy source for South Africa, ignoring the fact that water is an energy source too.

“Not only from a water perspective, but also from an energy perspective, the Drakensberg is a very, very important ecological region which needs to be looked after exceptionally well,” Schulze said. “There are all these dams that have been built and all these inter-catchment transfers that are taking place.”

Schulze pointed to the Tugela Vaal Transfer Scheme, which uses four dams on the border of KwaZulu-Natal and the Free State to generate hydropower. Woodstock Dam is the main water source for the scheme and water is transferred from the scheme via the Drakensberg Pumped Storage Scheme to the Sterkfontein Dam – both dams are bordered by application 12/3/346.

The Drakensberg is at high elevation, which makes it especially sensitive to climate change, he added.

“If the temperature in the Karoo is 36 and it goes to 38, there’s not much difference, but if it goes from 8 to 10 in the high mountains, you flip the ecology,” Schulze said. “We’re a water-scarce country, so it’s an area that really has to be developed in a very sustainable way – and sustainable means some, for all, forever.”

Energy source: A view of all catchments and rivers from Roland’s Cave near Cathedral Peak indicates the Berg’s potential to generate hydropower. Photo: Yuexuan Chen

Is fracking coming to the Berg?

At this stage, all applications are for non-invasive exploration only. It is not known if there are enough extractible shale gas reserves to make fracking profitable in the region, but environmentalists say their concern is, “what if they find something?”

Once aerial surveys start and if they find things, the next step is seismic testing, which is invasive, Howard from Frackfree said.

“Geologically, the Drakensberg consists of basalts, igneous rocks and not sedimentary rocks with any oil in it,” Schulze said. “However, further down there are sedimentary rocks at a lower altitude and I guess that is where people are looking at for hydraulic fracturing.

“I have not been following the fracking story very closely because I believe it will never get off the ground in KwaZulu-Natal. There is far too much social and ecological pressure to do it. And there are too many alternatives for energy.”

Rhino Resources owns Rhino Oil & Gas, which was founded by Patrick Mulligan, a Texas businessman and attorney who passed away last year. The office address for Rhino in the US is where Mulligan’s law firm used to be. Repeated attempts by #MineAlert to contact that office were not answered.

The corporate office address is a PO box in the British Virgin Islands, known to be an offshore tax haven. Many attempts to reach the Cape Town office and current chief executive, Phillip Steyn, for comment were also unsuccessful. The receptionist at the Cape Town office confirmed that Steyn is the only person in that office and she only knew of two other people in the company who are shareholders.

She also did not know any of the contact information for other Rhino offices. The company website hasn’t been updated since 2016, connection to the site is not secure and the site has a strangely basic design.

It is unconfirmed whether Rhino even has the financial and corporate resources to explore fracking in the region.

“Sometimes corporations speculatively obtain these applications to sell to other oil companies,” Rabie said.

Looking forward

A report by the Worldwide Fund for Nature in 2016 predicted that national demand for water will increase by 32% by 2030 as a result of population growth and industrial development.

“Who is going to make way for fracking?” Bell from Frackfree asked. “Are we going to take [water] from agriculture? Subsistence people? Municipal allocations?”

She labelled fracking as one of those technologies that is “just too destructive”. She pointed to the Strategic Environmental Assessment report for Karoo shale gas to show that the money South Africa could save from importing petroleum won’t outweigh costs like jobs lost to tourism, or the environmental and social effects of fracking.

“[When it comes to fracking], it’s not greenies versus people with money,” Bell said. “It’s how are we going to make it through the next 50 years? It’s a matter of health.”

When it comes to making policy decisions, Schulze said there is a fear that the government is thinking about short-term gains instead of long-term benefits. The big oil companies wield immense financial power over a relatively inexperienced government, he said.

“There’s no stability from the top,” Schulze said. “I don’t know how many ministers of water affairs we’ve had.”

Schulze previously sat on the board of Umgeni Water, when there were five technocrats and five human resources people.

“There’s not a single technocrat left,” he said. “We’ve politicised everything that should be run technically. As a technician, I couldn’t care who’s in the government – I’ve got to make sure the water is there for the people.”

Yuexuan Chen is a student majoring in biology and public policy at Duke University in the US. She served as an intern at Oxpeckers for two months