30 Jul How we (almost) became reptile smugglers

Cyberspace provides an anonymous, versatile marketplace for illegal wildlife trade. Rudi Bressa investigates how easy it is to set up illicit deals from Italy

Facebook feed: Once a post advertising reptiles such as this morph ball python is deleted, it’s gone, and as soon as the transaction has taken place, a seller will delete the post. Photo supplied

The internet is flourishing with websites, forums and groups where anyone can discuss and exchange information about the care of reptiles, and where it isn’t rare to find experts who turn their hobby into a moneymaker.

How is the global reptile market regulated? Is the internet facilitating illicit financial flows? The answer, according to our investigation, is affirmative.

Although most e-commerce platforms have banned the sale of wildlife commodities and specimens protected by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), it’s still easy to find almost anything. There’s no need to sink into the depths of the darknet, just take a look at the most famous social networks.

There are many ways to remain anonymous online. On Facebook, it is almost impossible to trace a specific post that shows up on your feed (unless you take a screenshot). Once a post is deleted, it’s gone, and as soon as the transaction has taken place, a seller will delete the post.

In closed groups on Facebook, it isn’t hard to find and buy specimens that can be traded with only a certificate attesting to their origin – though the platform’s Marketplace states that it is forbidden to sell and buy animals of any kind.

It’s easy to join these closed groups on Facebook, you don’t need to take any special steps. The groups’ names are often obvious, such as “Reptiles for sale in Europe”, while others have an ambiguous meaning – especially if you are communicating in Chinese or German, two of the most active markets internationally.

Once joined, the feed is constantly updated and most of the posts are sales announcements, with a price list and the scientific name of the species. Many of the traders seem to be regular breeders who openly declare the CITES origin of the reptile.

Whatsapp wrangle: This seller offers a wide selection of venomous snakes that are strictly forbidden in some countries, including Italy. Photo supplied

First online meeting

While monitoring the feed of one such closed group, we find a way to contact a seller based in Egypt. Our first contact takes place via email, showing interest in his commodities.

The seller sends an updated list with the scientific names of the reptiles, translated into English. Each species has a price, ranging from $3 for insects and snakes of little value up to $400 for an African spurred tortoise (Geochelone sulcata).

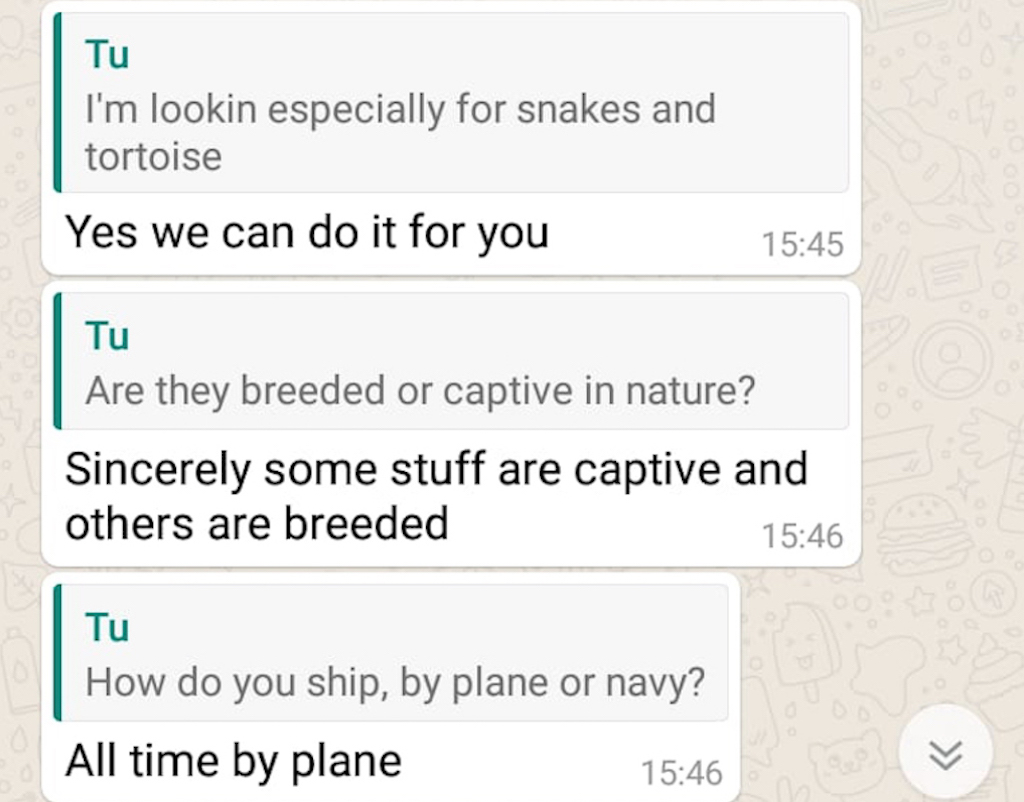

The seller also offers a wide selection of venomous snakes that are strictly forbidden in some countries, including Italy, such as the Egyptian cobra (Naje haje) and a Palestine saw-scaled viper (Echis coloratus), a venomous viper species endemic to the Middle East and Egypt. There is no shortage of Uromastix lizards and turtles, all species included on Appendix II of CITES – meaning they are species that are not necessarily threatened with extinction, but which could be so unless trade is strictly controlled.

We ask where the reptiles come from. “They are all captured in the wild,” says the seller via email. In response to our scepticism, the seller writes, “Don’t worry, we operated in this market for over 20 years”, and still have many “customers in Europe and Asia”.

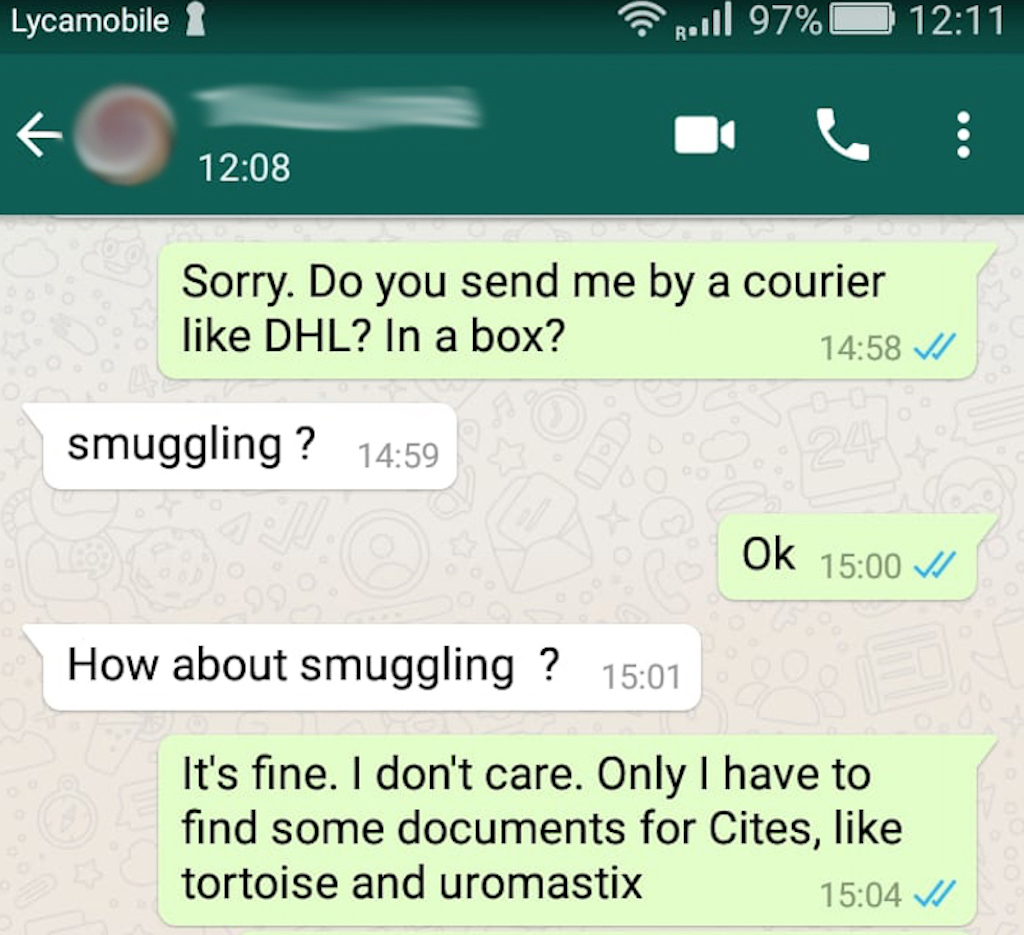

The conversation moves to Whatsapp, where we ask how the reptiles will be transported. “What about smuggling [them]?” responds the seller.

He asks us to place a US$3,000 minimum order, with an advance payment of 70% plus shipment costs. Delivery will take place by plane, he says, and the money transfer must take place through Western Union, an online payment method that would be difficult to trace.

The conversation ends after he asks if we have a licence to import reptiles to Italy. Because we have no intention of going through with the deal, we stop the communications and pass them on to a wildlife law enforcement contact in Italy, who confirms that the “seller could be dedicated to smuggling” and that the information will be passed on to relevant authorities.

Wholesale market: This seller in West Africa sends a shopping list that includes a wide range of mammals, birds, insects, amphibians, reptiles – hundreds of specimens. Photo supplied

African trader

A few weeks before the most awaited gathering in Europe of reptile traders, the Terraristika fair in Hamm, Germany, online posts and offers are increasing and the feed is constantly updated.

It’s in one of these posts that we meet a seller based in Togo, West Africa. Looking at his posts and pictures, it seems he has been working the market for a long time.

First contact is made via email: he sends a shopping list that includes a wide range of mammals, birds, insects, amphibians, reptiles – hundreds of specimens.

The seller explains that he “often sends goods to European countries”, and says “we have many customers all over the world. Many of them come from Asians [sic]. Obviously we have some in Germany and Italy.”

We ask where the reptiles come from. “Some are captured in the wild, others bred in captivity,” he replies.

The “shopping list” he sends includes protected species, such as royal pythons (Python regius), Calabar pythons (Calabria reinhardtii) and African rock pythons (Python sebae), at a cost of $30 each. There is also a wide range of tortoises.

We ask if the animals are all provided with documents and with CITES certificates. “Certainly, everything is done according to the laws,” he says.

Transport will be by airplane, at our expense, while payment must be made by bank transfer. He says sending the animals to Hong Kong can be arranged, but not to mainland China. It is not easy to do these type of transactions in Thailand these days, he adds.

Although he sends a CITES permit provided in Hong Kong to prove the legitimacy of his operation, he also says many of the animals are “caught in the bush” – indicating they are not captive-bred.

Once again, we end the communications and pass them on to a wildlife law enforcement contact.

This investigation is part of a transnational series investigating how online illegal wildlife trade facilitates illicit financial flow, produced with the support of the Money Trail project.

Rudi Bressa is an Italian freelance journalist and contributing author who writes about nature, conservation, climate change, energy transition and sustainable development. He has published several stories about poaching in Italy and contributes to LaStampa, LifeGate, Renewable Matter and other media.