28 Jun How Chinese Flying Money ‘finances’ illegal wildlife trade

Feiqian is the single biggest obstacle in investigating organised wildlife trafficking and related crimes, a year-long investigation by John Grobler established

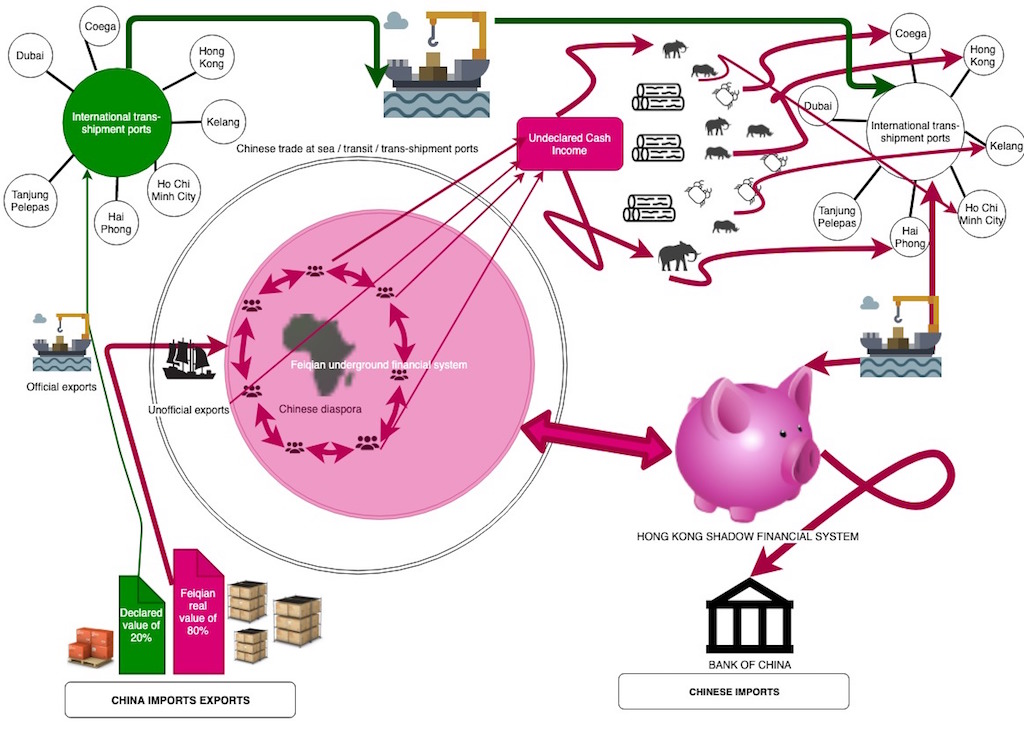

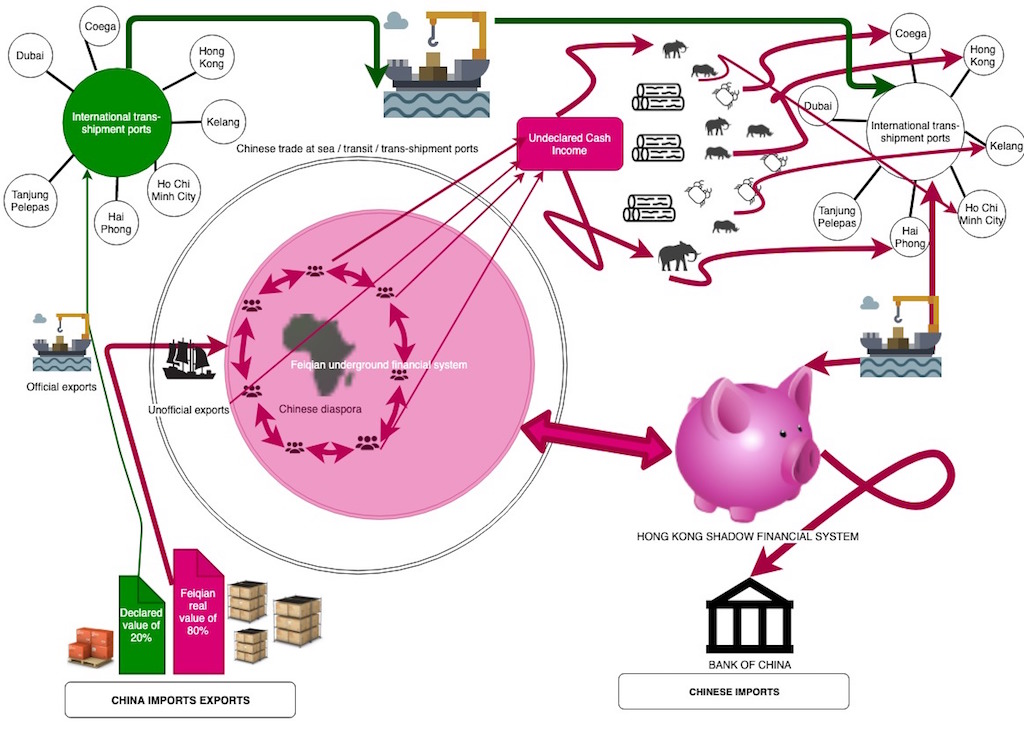

The secret key to Chinese success in Africa: How feiqian aka Chinese Flying Money works. Diagram: John Grobler

An ancient but highly sophisticated trade-based financial settlement scheme known as Chinese Flying Money, or feiqian, has emerged as the key enabling mechanism in the $260-billion-a-year international wildlife contraband market.

Illicit commodities function as a form of currency to enable wealth transfers outside the regulatory oversight of the international banking system, explained a former Singaporean finance expert who asked not to be named for his own protection.

“The trick behind feiqian is that the money never actually leaves China. It’s just the commodities that get moved around”, as part of a longer payment chain among the Chinese diaspora around the world, he said.

The seamless nature of global trade and the huge volumes of shipping containers handled on a daily basis enable the feiqian business to hide in the open, with containers of contraband shifting around like hard currency between Africa and the Far East.

It is a system of invisible and untaxed trade that has given Chinese business an edge in Africa’s construction sector, the untraceable income used to under-bid local competitors and grease palms for contracts.

At its most benign, it is a low-cost and trusted method of remitting money, much like the Islamic hawala transfer system. In its simplest form, Chinese Flying Money uses an established Chinese account holder abroad as a channel to add smaller amounts to an official invoice to a supplier, with the supplier then paying out the extra amount in cash on the receiving end.

Unlike straight barter trade, feiqian is not a straight swop but rather an exchange in stored value that leaves no paper trail except for in the books of the operators of secretive underground Chinese banks. Modern systems have morphed over 1,200 years from the time feiqian first developed as a rice-trading system during the Tang Dynasty.

What makes it even more impenetrable is that it appears mostly to be operated by elderly, well-established women in a closed-off network of mutually trusted contacts, a year-long investigation established. It is also the single biggest obstacle in investigating organised wildlife trafficking and related crimes such as the drugs-for-abalone trade in the Western Cape.

Over the past 10 years feiqian has become increasingly visible in the surge in wildlife contraband trade, stimulated by a global shortage of hard currency. However, two requests to China’s official representative in Windhoek to discuss the system and its impacts in Namibia were declined.

Lots of business but not many visible clients: Hong Kong as the largest seafood market in the world is the feiqian system’s front door into mainland China. Photo: John Grobler

Hardwood smuggling

Regionally, it has become visible in an increase in hardwood smuggling across Africa from any country with deep forest resources but non-convertible currencies, weak administration, poverty and entrenched corruption. Deeply indebted countries prove especially vulnerable to the deep ecological and economic damage wrought by the destructive hardwood trade, research shows.

For example, when the 2014 global oil price collapse saw foreign banks refusing to sell Angola any United States dollars until the country had settled its outstanding debts, Chinese traders in Angola started converting their worthless local currency, or kwanzas, into rosewood logs that were (mostly) smuggled out via Namibia to China – where the timber was sold for very convertible Chinese yuan.

In the multibillion-rand drugs-for-abalone trade in South Africa, this non-linear payment system has defeated all attempts at linking intercepted illicit drug or abalone shipments to specific Chinese buyers known to have been operating in the Western Cape since the early 1990s.

“How do the poachers get paid for hundreds of tons of abalone?” asked Marcel Kroese, a former head of enforcement at the then-directorate of economic affairs and fisheries who is now an international fisheries consultant. During his stint at the directorate, there was only one conviction of a syndicate involving a Chinese collaborator in an elaborate value-added tax scam, despite evidence that huge amounts of cash were being passed around.

“So who has the cash, where was it all coming from?” Following the money as a means of identifying the main Chinese players yielded zero results. “We could not ever find the [source of] money,” Kroese said, making water-proof court cases relying on formal paper trails a major practical, legal challenge.

Hou Xuecheng, implicated in the looting of Namibia’s hardwood resources, is out on bail in connection with ivory and other wildlife contraband-related offences allegedly committed in 2012. Photo: The Namibian

Balance of payments

Feiqian also occasionally appears as a gaping hole in individual countries’ balance of payments accounts with China, as Namibia has discovered in an ongoing R3.1-billion import tax fraud investigation involving Jack Huang, a business associate of Namibian President Hage Geingob.

Huang (51) and Laurensius Julius (42), a former Walvis Bay customs official, are to face trial together with six Chinese citizens on 3,215 charges of fraud and money-laundering in the Windhoek High Court on July 5.

The first suspects were arrested in December 2017 and Huang two months later after the Ministry of Finance discovered a huge discrepancy between the declared value of goods imported and the actual remittance of payments to China in Julius and Huang’s customs clearing activities between Walvis Bay and Oshikango, on the border with Angola.

The state charges that Huang, Julius and their co-accused had from 2013 to 2016 imported a declared value of goods of R213.4-million from China while remitting payments exceeding R3.1-billion, allegedly defrauding Namibia by misrepresentation and money-laundering.

While Huang and Julius are the high-profile suspects as the front operators of the alleged scam, the real feiqian operators were four elderly women charged along with them, said a source in the local Chinese community. One suspect has died in China and another has absconded, with the rest pleading not guilty to all charges and currently out on bail.

Where the contraband found its way into the feiqian payment chain is the manner in which small Chinese traders operate everywhere in Africa: cash only, and most of it off the books. In practice, it amounts to systemic tax fraud: Chinese operators routinely under-declare the value of cheap goods which are then sold for undeclared and unreported cash.

For example, Julius allegedly used his knowledge and access as a former customs official to help his Chinese clients evade taxes by importing cheap clothes disguised as rolls of material instead of finished garments, said a former colleague who asked not to be named for fear of retribution.

Julius then allegedly set up his own customs clearing business, working only with Chinese clients – and soon he was rolling in money, acquiring a seaside mansion and a fleet of 70 fuel transport trucks in the space of three years.

So where did the extra R2.8-billion come from that they remitted to China? This was all feiqian money, made off the back of dodgy state construction deals, with the Chinese collaborators using BEE contractors for fronting, said a well-placed Chinese source in Namibia who asked not to be named.

Typically, this extra cash flow is then used to acquire a high-value and often illicit local commodity, sometimes by syndicates to spread the risk of confiscation, the source explained.

The most obvious such commodity is African rosewood. Huang is the registered owner of XYZ Trading, one of two Chinese transport companies recorded trucking loads of illicitly harvested African rosewood to Walvis Bay. He has boasted openly on social media about being able to avoid using commercial banks by using the “Chinese way” of transferring money.

Another Chinese businessman implicated in the looting of Namibia’s hardwood resources is Hou Xuecheng, who is out on bail in connection with ivory and other wildlife contraband-related offences allegedly committed in 2012. Hou’s former partner Hui Wang, who has also been implicated in rosewood trading, is serving 14 years in jail after he was convicted of attempting to smuggle 14 rhino horns out of Namibia in 2014.

Asked about his role in rosewood trade in Namibia, Hou said he was “only the transporter”, but research indicates he is being paid in rosewood in China for his services.

This is typical of feiqian: the initial investment made in “black money” is doubled by buying up cheap goods in China – again, on syndicated, whole-sale basis – and the goods are then imported at under-declared value, yielding a profit that is often transferred between the parties as loans.

What makes feiqian so suited to smuggling is the fungible nature of all precious contraband: every kilogramme of rhino horn, ivory, abalone, shark fin or log of precious hardwood can be divided up into smaller parts of itself to make those more trade-able at lower values and volumes.

Where the Western Cape abalone, smuggled via Walvis Bay in Namibia, ultimately ends up: one such shipment was tracked to this non-descript building in New Territories, Hong Kong, close to the border with mainland China. Illicit abalone is laundered into the informal trade by taking advantage of Hong Kong’s lower tax rates as Special Administrative Zone. Photo: Alex Hofford

Harvesting money

This singular characteristic is a major clue to what has been at least partly responsible for the surge in poaching of rhinos and elephants in Africa since 2008: speculation, driven by the fact that the syndicates are literally harvesting money. Rhino horn has become more valuable than gold, not for its inherent value but for its exchange value.

After the Convention in International Trade in Endangered Species (Cites) gave the go-ahead for several African countries to conduct a once-off sale of their ivory stockpiles in 2009, in an attempt to drive down black-market prices, poaching in Africa surged, wiping out up to 60% of elephant herds in East and southern Africa, according to the Journal of African Elephants.

This was a simple illustration of both feiqian and the law of price demand, which holds that making a scarce and valuable commodity more readily and cheaply available will increase demand and, as result, price for that commodity.

Instead of selling their newly acquired ivory, the Chinese buyers stockpiled it because actual demand for ivory in China was static or declining, according to TRAFFIC, a Hong Kong-based NGO that monitors global wildlife trade.

The poaching surge was driven by individuals like the notorious “Ivory Queen”, Yang Feng Glan (69), sentenced in February 2019 to 15 years in jail by a Tanzanian court for her part in smuggling USD$6.5-million in poached ivory to China over the past decade.

Glan was convicted of smuggling 1,889kg of ivory – about 350 elephants’ worth – but investigators like the late Wayne Lotter, assassinated two years ago in Dar es Salaam, believed she was handling much more ivory than that.

Most of Glan’s business was conducted by shipping container, so many of the thousands she dispatched to China may have contained other contraband. Her defence in court did not reveal how much of that was for her own account.

With millions of containers annually being stored and trans-shipped through free ports like Coega in South Africa, Dubai, Tanjung Pelepas and Kelang in Malaysia and China’s Hong Kong, a container concealing contraband may not cross any customs point while ownership on paper passes through half a dozen hands in as many countries.

Changing bills of lading and destinations of shipping containers at sea or stored in a port is expensive, but it is a common practice in business, said a veteran Walvis Bay-based shipping agent who asked not to be named for reasons of safety. The middleman would not want his client to know who his supplier is in fear of being cut out, and will therefore do a “switched bills of lading” to hide the origin of his goods.

While such shipments from suspect ports are often red-flagged by customs officials, the volumes passing through trans-shipment ports are so enormous it amounts to chasing one needle through six mega-haystacks, he said.

“If you know the shipping routes, as any halfway-decent shipping agent would, you could play ping-pong with that container [of contraband] between the trans-shipment ports forever,” said the shipping agent.

A senior state prosecutor investigating abalone cases in South Africa said disrupting feiqian will be difficult, until Chinese citizens in Africa play by same rules as everyone else. The only way to enforce that would be to crack down on their cash-only business practices, she said.

This investigation was developed with the support of the Money Trail Project. Editorial support was provided by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project

This investigation was developed with the support of the Money Trail Project. Editorial support was provided by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project