08 Mar Exposing the abalone-rhino poaching links

John Grobler investigates the overlap between abalone and rhino horn smuggling syndicates operating between South Africa, Namibia and Hong Kong

Question marks: The Chinese residents had acquired properties in Plattekloof Extension 3 to the sum of R16.17-million between 2011 and 2016, mostly paid in cash and without any visible means of a formal income. Illustration: John Grobler

A transnational abalone smuggling syndicate has been hiding out in plain sight in a luxury Cape Town suburb since 2005, seemingly protected by the very officials responsible for combating poaching and prosecuting organised crime.

Although several of the syndicate’s members have repeatedly been arrested since 2006, the National Prosecutions Authority (NPA) and Directorate of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry (DAFF) in Cape Town could not explain how ringleader Jiangliang Li, also known as Jieyan Li, was still at large in spite of being arrested twice in recent years for abalone-related offences.

The syndicate was identified in a six-month-long investigation into the overlap between abalone and rhino horn smuggling syndicates operating between South Africa, Namibia and Hong Kong.

The trail started with a fugitive smuggler named Zhi Geng in Namibia, or Zhi Wen Cheng in South Africa, who was identified as one of the kingpins of abalone and rhino horn smuggling from South Africa and Namibia to Hong Kong via the Northern Cape.

Re-tracing the source and route for a shipment of abalone and rhino horn that Geng and his accomplice, James Baron Wallace, were caught with in Windhoek in February 2016 to its intended address in Hong Kong led to an abalone-dealing company called Blue Ocean.

This in turn connected Geng to a group of Cape Town-based families who were discovered to be not only some of the main buyers of illicit abalone in the Western Cape, but also at the centre of syndicated rhino horn smuggling in Namibia.

The inter-relationship of these families was not immediately obvious because they alternate between their middle names and the Mandarin and Cantonese versions of their names, which translate differently into English and so obscure their common origins.

What they all had in common is an interest in expensive property and a superstitious adherence to certain numbers in doing their business, it emerged.

The group’s Cape Town property acquisitions, timed to correlate with their respective birth dates in an intricate, hierarchical fashion, was ultimately what revealed their inter-relationships and suspected money laundering.

Deeds Office records showed that two of them, aged 18 and 22 years at the time and with no visible formal income, had between July 2011 and February 2012 spent R10-million in cash buying up four of five adjoining mansions on one corner at the top end of Geelhout Crescent in Plattekloof’s Extension 3.

The syndicate’s influence was most visible in the Western Cape, the only source in Africa of the highly prized but slow-growing Haliotis midae, in the proliferation of gangsterism associated with the illicit abalone and drug trades, and the near-extinction now of wild Cape abalone since 2005.

Lie of the land: Abalone poachers took full advantage of an over-stretched police force to start poaching on an industrial scale. Illustration: John Grobler

POISON-THE-WELL POLICIES

Up to 2004, the abalone resource had started recovering slowly from historical poaching as effective policing by joint patrols by South African National Parks (SANParks) and the South African Navy kept it at bay, if not under control.

Between 1994 and 2004, abalone poaching was typified by three types: for own use, for selling for cash for drugs or swopping abalone for drugs, and by members of the drug-selling gangs looking to improve their standing by generating extra cash, said Bryan Minnie, a former senior South African Police Services (SAPS) Crime Intelligence officer.

But when the ANC won political control of the Western Cape for the first time since the end of apartheid rule in 1994, the joint navy-SANParks patrols were suddenly cancelled and responsibility for policing the abalone resources turned over to SAPS.

This was a major boon to the abalone poachers, who took full advantage of an over-stretched police force to start poaching on an industrial scale – as reflected in Hong Kong’s abalone import data for 2005 to 2016.

Since then, Minnie said, organised abalone poaching was run by two groups divided roughly along racial lines: organised criminal gangs associated with The Numbers, a prison-based gang of coloured and black members, and by white professional divers with fast boats, cars and sophisticated communications equipment.

But so far, only the professional poaching gangs were being bust, Cape Town High Court records going back to 2006 showed – while the Chinese perpetrators kept slipping away to re-start operations from the same suburbs in a radius of about 30km around Plattekloof.

Following the general elections of April 2009, then president Jacob Zuma moved fisheries from the Ministry of Environmental Affairs to Agriculture and appointed Tina Joemat-Pettersson, a trade unionist from the impoverished Northern Cape capital of Kimberley, as its new minister.

In 2011’s provincial elections, the Democratic Alliance won the Western Cape by a narrow margin – and from that point onwards, the ANC appeared to be following a poison-the-well policy vis-a-vis the informal fishing industry in the province.

‘Mr Big’: SARS seized Quinton Marinus’s luxury house in Plattekloof Extension 2 for unpaid taxes. Source: Cape Argus

GROUND ZERO: GANSBAAI

In effect, it amounted to selective morality, dictated to by private interests. “The ANC does not really want to rule in the Western Cape province, but they want to do the [drug and abalone] business run by the Cape Flats gangs,” said Annie Robb, a former operative of ANC’s military wing now living near Gansbaai, the epicentre of the abalone poaching in the Overberg area.

What revolutionised abalone poaching was the advent of cellphones, corruption and starving the local police of resources: in Gansbaai, only two out 17 police vehicles were operational, Robb pointed out.

Drugs and abalone formed part of one huge regional but centrally controlled syndicate, she said. “The poachers run everything here, from Cape Town to Gansbaai,” and appeared to be all one large family, she said.

Under Joemat-Pettersson, the fishing communities of the Overberg area were denied their traditional fishing and abalone harvesting rights, effectively pushing them into organised crime by forcing them to resort to poaching to make a living.

Rising unemployment also saw a sharp increase in drug use among the youth in the local communities – all part of a deliberate policy to radicalise them and, in effect, make the Western Cape increasingly ungovernable, Robb said.

On May 2 2015, in the run-up to the next round of provincial elections on May 18 2015, Zuma met secretly with Quinton “Mr Big” Marinus and Igshaan Davids, two of the top alleged Cape Flats gangster bosses, at his official Tuynhuys residence, investigative news agency AmaBhungane reported in the Mail & Guardian newspaper of November 20 2015.

The meeting was also attended by other community leaders and members of the Griqua royal family from the Northern Cape, AmaBhungane reported their sources as saying.

Zuma wanted their support for wrestling control of the Western Cape back from the DA, in return for which he said he would “look into” their tax problems with the South African Revenue Service, AmaBhungane reported. SARS had recently seized Marinus’s luxury house in Plattekloof (in Extension 2) for unpaid taxes, they added.

This meeting was preceded by a preparatory meeting arranged by Durban underworld figure and Zuma family associate Lloyd Hill at a business boardroom in Saltriver. Hill told the group their support would be rewarded with business opportunities, using an unnamed nonprofit company as a vehicle, according to AmaBhungane’s sources.

This time, the tactic failed: the DA went on to win 59.4% of the vote. But gangsterism in the abalone industry started becoming more violent than ever, marked by shoot-outs, hi-jacking of abalone shipments and armed raids on abalone farms.

The plight of the informal fishing community, still denied access to the only natural resource available to them, became more desperate than ever, according to their testimonies to a parliamentary committee.

Corruption in the Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries’s offices, as subsequent arrests in March 2018 were to show, had become rife, with officials confiscating abalone from small poachers and selling it back to the organised syndicates.

Abalone factory: The rented house at 26 Geelhout Crescent that was turned into an abalone drying plant by the Chinese syndicate’s South African and Zimbabwean operators. Photo: John Grobler

FLYING MONEY

A few kilometres away from Mr Big’s confiscated home in Extension 2 of Plattekloof, the Chinese families in Extension 3 were flourishing.

The first Chinese national who moved there, official property records showed, was Sun Fun Lai (born 5/6/1954), a bachelor who sold the house situated on Erf 20819 (27 Geelhout Crescent) on 2/11/2001 for R1-million to Ling Lin (born 1/11/1971) and Sophia Sherene Lin (born 30/8/1980).

The only bond issued among all five properties was for the house at 27 Geelhout: a mortgage of R500,000 registered on 1/2/2002.

The next Chinese arrivals were Jieyan Li and his 22-year-old daughter Jieyi (born 30/7/1989), who bought Erf 20818 (29 Geelhout) in Jieyi’s name for R2.17-million in cash on 7/7/2011.

Four months later, on 3/11/2011, the then 18-year-old Ka Kit Cheng (born 5/7/1993) bought the adjoining properties on Erf 20817 for R3.1-million, and another four months later, on 24/2/2012, also the properties on Erven 20816 and 20815 for R2.85-million in cash each.

Property records further showed that Ling and Sophia Lin then on 18/9/2014 bought a second house situated at 21 Cambridge Crescent in the upmarket gated community of Baronetcy Estate in Table View for R2.09-million in cash.

They also acquired two business premises at the Century Century mega-mall Montague Gardens on 29/4/2016 and 20/5/2016 for a total of about R2.1-million, paid in cash.

All told, this group of Chinese residents had acquired properties to the sum of R16.17-million between 2011 and 2016, mostly paid in cash and without any visible means of a formal income, in the case of the Li and Chueng families.

Ling Lin appeared to have opened and closed several businesses: Coalition Trading 114 CC, registered on 26/2/2003 and Travel Revolution CC on 12/8/2003. These companies had since been de-registered, according to CIPRO records.

Li owned or controlled two companies: Colourful Holdings CC, registered on 16/4/2015 as well as Chop Chop Steak Bar CC, registered on 26/4/2017. Both recorded their registered places of business as Lin’s home at 27 Geelhout Crescent.

There was no restaurant of any kind at 27 Geelhout – which at any rate would have been illegal under local zoning laws, neighbours said. In several visits to this address, no other cars except one luxury German sedan (parked and not moved once from November to February) could be observed at this address. No one would answer the doorbell and the house appeared neglected.

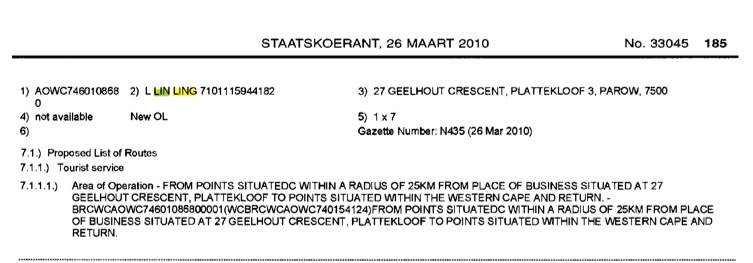

Li Ling’s taxi licence: Neighbours said the only taxi-type vehicle ever regularly seen in the neighbourhood was a Mercedes Benz Vito van with dark windows that would arrive at 10h00 every morning at the rented house at 26 Geelhout Crescent. Source: Government Gazette

THE TAXI & 26 GEELHOUT CRESCENT

In March 2010 Li Ling was granted an official taxi licence for a vehicle of seven passengers operating in a radius of 27km around Bellville. This in itself was unusual, as the Cape Flats taxi industry is heavily politicised and controlled by the Cape Flat gangs – and the Bellville area is a prime taxi route area.

The neighbours said the only taxi-type vehicle ever regularly seen in the neighbourhood was a Mercedes Benz Vito van with dark windows that would arrive at 10h00 every morning at the rented house at 26 Geelhout Crescent, two houses downhill from the Lin and Li families’ houses.

The young white driver would then park inside the garage, directly attached to the house by an internal door, where it would remain until 16h00, when it would leave again. Sometimes, it drove first drive up the hill past 29 Geelhout Crescent before turning around and driving downhill out of the neighbourhood, said one neighbour.

The house, rented from an old Indian couple for R25,000 a month, did seem odd: the two young Zimbabweans who were staying there (who claimed to be gardeners) never put out any rubbish bins, but cats appeared to be strangely attracted to the place: “All the cats in the neighbourhood kept jumping over the [back] wall,” said another neighbour.

The penny dropped in February 2017, when the police raided the house: turned out that it was an abalone drying house, its windows boarded up to prevent the strong smell of cooking abalone from reaching the neighbours.

A local newspaper later reported 12 suspects had appeared in court on abalone-related charges, following arrests made at addresses in a radius of about 30km north of and including in Plattekloof: Durbanville, Table View, West Beach, Atlantic Beach and Parklands.

Among those arrested were two Chinese suspects: Lee Ngok Sui (56) and “Andrew” Lau (30). Their surnames are the Cantonese variation of the surnames of the two partners in Blue Ocean in Hong Kong, namely Yin Sum Chiu and Chen Luk Lai.

‘The old man’: Jiangliang Li, also known as Jieyan Li, was still at large in spite of being arrested twice in recent years for abalone-related offences. Photo: sourced

NAMIBIAN BORDER

Around the same time, a WhatsApp crime intelligence report, circulated among police reservists and shared later with this reporter, stated that a certain Li Jieyan was arrested in the Northern Cape near or on the Namibian border, about 700km north of Cape Town, with two pick-ups full of abalone worth R6.5-million as well as two ivory tusks.

A luxury SUV registered in Li Jieyan’s name listed his home address as 29 Geelhout Crescent, two houses uphill and over-looking the rented abalone-drying house. A vehicle fitting its exact description was seen parked in the enclosed parking area by this reporter.

There was, however, no police activity ever at 29 Geelhout Crescent, home to “the old man” as Li Jieyan was dubbed by investigators, a neighbour said: the young couple and the old man who lived there kept a very low profile.

Two neighbours identified the old man living at 29 Geelhout as Jieyan Li by a picture, circulated on this closed social media group, showing a Chinese man in his early 50s, in handcuffs and standing behind a white panel van with some cash on the floor.

Were DAFF, the National Prosecuting Authority and the Hawks aware of this abalone connection between 26 and 27 Geelhout Crescent? While all expressed interest in this information, none of them would confirm or deny anything and stopped responding to emails or phone calls. They were not willing to confirm anything, not even the arrest of “the old man”, Jieyan Li.

High Court ruling: Velddrif harbour in the small West Coast fishing village from where the Chinese syndicate exported abalone disguised as canned fish bait. Photo: John Grobler

GANSBAAI – WEST COAST CONNECTION

This was not the first time the authorities had encountered this Chinese syndicate.

A Cape Town High Court ruling by Judge J Gamble in September 2017, in connection with an abalone case dating back to 2006, showed that a shadowy Chinese syndicate was the main driving force behind the poaching.

The 256-page judgment set out in detail how the Chinese syndicate had used low-grade pilchard, packed as bait, to hide abalone shipments to Hong Kong, using the numbers 3 and 4 to secretly identify their hidden loot.

Although 19 men were initially arrested, only nine eventually faced trial after key suspects – “Richard” Chao, Jyeng Chang Ku, Wei Lui Lui and Stanley Dlamini – skipped bail and disappeared. A fifth suspect, a Michael Chang who owned the truck used to smuggle abalone to Namibia, also absconded after the bust.

Testimony by one of the accused, Pieter du Toit, made it clear that the Chinese were running the syndicate, Judge Gamble found: “… we found that accused 10 Richard Chao was obviously the manager of the enterprise…

“This fact was later confirmed when accused 4 took the witness stand and described his working relationship with Chao… The import of his evidence was that Chao was in effective control of the enterprise, whose principal business it was to export abalone overseas,” Judge Gamble found.

The nine remaining accused were found guilty on most of the organised crime charges. While the Chinese suspects disappeared, their syndicate was to resurface five years later in another major abalone bust.

In 2010 the Hawks raided two rented houses in Table View and Parklands, just north of Plattekloof, and a warehouse in Vredenburg, about two hours’ drive further north of Cape Town, seizing R20-million worth of abalone and arresting four men: Sean Kruger and his father Cecil Kruger, Albi Bucchianeri and Busobenkosi Matera.

Two containers of abalone were also later recovered from Hong Kong and a fifth suspect, Zhi Cheng Wen, was charged. He appears to have evaded arrest by slipping across the border into Namibia – where he is known as Zhi Geng, according to a source who knows him personally.

Their illegal abalone smuggling enterprise, as set out in the charge sheet, showed close coordination with Li Ling’s business dealings: on March 30 2010, just as Lin’s taxi licence was granted, Sean Kruger rented a warehouse in Vredenburg, two hours’ driving north of Plattekloof.

On April 14 2010, he and Bucchianeri had set up their front company Virdon CC while Kruger Senior and Matera respectively rented houses at 4 Northridge Road in Parklands and 88 Briza Street, Table View, to use as abalone drying plants before moving the product to the Vredenburg warehouse where it was packed in shipping containers they then shipped to Hong Kong.

Between April and August 2010, this group and other unknown persons then collected, prepared and packaged nearly 100,000 units of abalone for export to Hong Kong before being bust.

All were granted bail – and it was to take another seven years before the four men were eventually convicted of racketeering and sentenced to a record 137 years in the Khayelitsha Regional Court in February 2019.

Economic alternative: The Port Nolloth abalone farm, where owner Jianliang Li and his manager were caught drying illegal abalone at the back of the plant. They appealed their arrest under a special clause in South African criminal procedure law. Photo: John Grobler

NAMAQUALAND AND NAMIBIA

Sean Kruger next popped up in Port Nolloth in the Northern Cape, where Denver Barron, president of the Fisheries and Mariculture Association, introduced him to Quiryn Snetlage, a former diamond diver turned pioneering abalone farmer.

The association was an initiative of the Northern Cape provincial government’s economic development department to develop mariculture as an economic alternative to the declining local diamond mining industry, Snetlage explained.

Kruger was hired by Rockefeller Kelp, an empowerment company which was granted a kelp farming concession for the area. Kelp is what abalone feeds on, and the idea was that they would develop the resource to supply the abalone farms on the Eastern Cape coast with abalone seedlings and the kelp to feed them.

The business relationship lasted less than two months before Kruger was back to his old poaching ways, using teams of unemployed young local divers to strip their carefully managed abalone seabeds at night, Snetlage recalled bitterly.

Kruger was “very involved with the Chinese” who were to eventually take over Port Nolloth Sea Farms, the abalone farming business that Snetlage had started before Kruger’s pilfering nearly ruined him, said a still-angry Snetlage.

The Port Nolloth Sea Farm had changed hands a few times since he sold out and last he heard it was taken over by a Chinese national and a Malaysian named Ma under the name Port Nolloth Abalone Farms, he said.

Kruger also took advantage of another, relatively unknown aspect of abalone farming: the use of ephedrine as a growth stimulate for the abalone seedlings, and also the base chemical for drugs like tik, a dangerous but cheap meta-amphetamine derivative that has ravaged communities in Northern, Western and Eastern Cape.

In 2013 or 2014, Kruger was caught transporting a large bag of tik from Port Nolloth to Kleinzee, the former diamond mining town 40km south where he was living with his family at the time. He got off on a technicality in court, said the police officer who had arrested him.

DAFF stonewalled all queries about the new concession holders’ identities – for several political reasons, as it subsequently would emerge.

Mostly, Zhi Geng was doing a lot of driving: Between Walvis Bay and China Town, a complex of warehouses in Windhoek, up to the Oshikango border post with Angola, to Rundu and to Katima Mulilo on the border with Zambia, and trips down to the South African border. Illustration: John Grobler

ORANGE RIVER BORDER TO WALVIS BAY

Zhi Wen Cheng, now calling himself Zhi Geng, arrived in Walvis Bay in the latter half of 2011, said a source who knows him personally. A copy of his passport, issued May 28 2015 by the Chinese Embassy in Maseru, Lesotho, stated his place of birth in remote north-eastern Liaoning Province in China on July 12 1979.

The source said Zhi Geng had later confided that he had nearly been caught smuggling rhino horn into China earlier that year, making his escape just as the airport police were collaring his hired mule carrying the suitcases with the rhino horns. Geng’s arrival in Namibia was to mark a surge in poaching of Namibia’s critically endangered black rhino population.

Local businessman Harald Blum recalled Geng as “Jack”, a cocky young guy who operated from a rented office in the former Walvis Bay town library with nothing more than just one desk, chair and a landline telephone. This was odd, seeing that “Jack” also carried several mobile phones on which he was constantly talking away, said Blum.

Whatever he was doing, he appeared to be successful: soon he was driving an expensive, late-model German sports car with “Sky Blue” personalised plates. The flashy car – later reported as stolen in South Africa, said Blum – got him officially noticed by local law enforcement agencies trying to stem the rising poaching tide and looking for suspects who fitted what is a typical smuggler’s flashy profile.

Mostly, Geng was doing a lot of driving: between Walvis Bay and China Town, a complex of warehouses in Windhoek, up to the Oshikango border post with Angola, to Rundu and to Katima Mulilo on the border with Zambia, and trips down to the South African border.

Evidence led in the case of Stephen Miller and his eight co-accused in their trial showed the abalone was being smuggled into Namibia by a truck that was owned by a Michael Cheng, who fled South Africa after Miller and the others were arrested.

A truck owned by Fysal Fruit, a fresh-produce distributor and trucking company closely linked to the families that police say run the Cape Flats gangs, was also confiscated in 2014 by border police after a shipment of abalone was discovered among the other goods.

Fysal Fruit and two other Cape Town-based fruit and vegetable wholesalers had branches in Walvis Bay and Ondongwa, close to Oshikango on the Angolan border, said Ivan Marshall, a Walvis Bay businessman, community activist and anti-drug campaigner.

Walvis Bay has a major drug problem, and their information was that trucks belonging to those companies were used – knowingly or not – to transport drugs from South Africa to Namibia, said Marshall, an accusation confirmed by the Namibian Drug Enforcement Unit.

The drugs – and likely the abalone as well – were typically hidden in the middle of pallets of fruit and vegetables in the refrigerated trucks, he said, just as had emerged in court in the Miller case in Cape Town.

More than 800 refrigerated trucks cross the border at Vioolsdrift every month, making it impossible to search all of them, said Vioolsdrift border police commander Colonel Wessie van der Westhuizen.

With day-time temperatures often exceeding 50 degrees Celsius, there was always a risk that any unwarranted search could cause especially frozen goods to go off, and so expose the police service to civil claims, he explained.

Risky business: The old Hawston fishing harbour, empty except for flowers strewn in a funeral service for two poachers who did not return from the sea. Photo: John Grobler

THE HAWSTONE-KIMBERLEY CONNECTION

James Barron Wallace, who was charged with Geng for illegal possession of abalone, said they met through the semi-precious gemstone trade. A native of Hawston (a hive of abalone poaching, like Gansbaai), he admitted to dabbling in the Chinese abalone business in the 1990s, but said he gave it up because of the strict new laws and prohibitive penalties when he got married and moved to Namibia.

He said he had sold several parcels of tourmaline to Geng and exported those to China on Geng’s behalf over the years. He claimed that Geng had asked him to verify if abalone was legal in Namibia and what export permits were required and he made a phone call to the Namibian police’s Protected Resource Unit (PRU) – only to be promptly arrested.

While abalone is not explicitly mentioned under Namibia’s Fisheries Act, it is covered under Appendix I of CITES, said the PRU’s Chief Inspector Louretta Tsuses. The PRU then searched Geng’s rented townhouse in a luxury complex close to the Chinese Embassy in Windhoek and discovered 95kg of dried abalone and 1.5kg of rhino horn, cut into 27 pieces.

Charged with possession of rhino horn in addition to the abalone, Geng and Wallace were granted bail of N$250,000 and N$30,000 respectively and were required to hand in their passports. Seven months later, Geng skipped bail and disappeared, leaving the state no choice but to withdraw charges against Wallace.

Geng was now believed to be hiding among the huge Chinese community of Bruma Lake in Johannesburg. He did, however, leave clues behind that were to lead to the syndicated rhino horn smuggling operation in Namibia which, like the rest of the abalone syndicate, was hiding in the open all along.

Vioolsdrift on the Orange River border, crossing into Namibia: Border police searched a luxury sedan with two men crossing into South Africa and discovered R2.4-million in South African currency hidden behind the door panels. Photo: John Grobler

BACK TO THE BORDER

In early January 2018 the Port Nolloth police, acting on a tip-off, searched the abalone farm premises and discovered a cache of illegal abalone being dried in a separate room, said a senior Northern Cape police source. Two men – Jiangliang Li and Hendrick Reynders from Hermanus – were arrested, this source said.

Northern Cape Regional Court prosecutor Wentzel Engelbrecht confirmed the arrest, but said because the suspects had appealed their arrest under a special clause in South African criminal procedure law, the names could not be released until a ruling was made by the Cape Town High Court.

Engelbrecht also said he was not aware of Li Jieyan’s arrest a year earlier near the Nakop border post by the Hawks. When showed the WhatsApp picture of Li in handcuffs, he ceased communicating.

On February 2 2018, the Vioolsdrift border police searched a luxury sedan with two men crossing into South Africa and discovered R2.4-million in South African currency hidden behind the door panels. The Chinese passenger – Dang Yin Chen, born October 7 1977 in Hanan Province – said the money belonged to his brother who owned two shops in Mariental, Namibia.

Chen’s passport showed that he had flown from China to Cape Town on December 24 2017, and on December 31 to Windhoek. Some of the cash was still wrapped in paper that showed it was withdrawn in tranches of R100,000 at a bank in Ongwediva – about 1,000km further north of Mariental.

His driver, one Stanisraus Jemim from Rundu, carried an unusually numbered passport – T0010283 – a type of passport usually only issued to national security officials.

Jemim was employed by Stina Wu, a Chinese businesswoman who owns several shopping malls and who had told the Namibian police that Zhi Geng was her employee after his arrest in an attempt to secure bail for Geng, said Chief Inspector Louretta Tsuses of the Protected Resources Unit.

On March 23 2018, the Hawks raided the DAFF offices in Gansbaai, arresting nine employees on charges of racketeering and corruption, including Steven Baadjies, a nephew of celebrated Umkontho we Sizwe veteran Clement Baadjies.

They also arrested eight other suspects in the greater Overberg area, including long-suspected abalone kingpin Ernie “Lastig” Solomons and Preston Julius for what the NPA’s advocate Nico Breyl said was a scheme whereby DAFF inspectors were selling poached abalone they confiscated back to the poachers.

Among this group were the DAFF employees who allegedly took a R1.9-million back-hander from Shamode Trading’s Deon Larry.

Larry could not be located to question about his alleged relationship with the Chinese group, but in a 2013 Appeals Court ruling confirming his conviction for indecent assault on a schoolgirl in 2013 pointed at a long-standing relationship between Larry and a certain Chinese national, referred to in the evidence as “the old man”.

Evidence led in the case showed Larry had told the schoolgirl, whose family was experiencing financial difficulties and had lost their house which was then bought by Larry on an auction, that he knew a Chinese man who would sponsor her studies.

He then took her to an empty house in Rosendal, Delft, where an “old Chinese man” was waiting outside while Larry took her into one of the bedrooms and tried to force himself upon her, Judge LJ Bozalek found.

Powerful connections: 29 Geelhout Crescent, where the metallic-bronze Land Rover Discovery Li was driving when arrested at Ariamsvlei was traced back to and found parked in the driveway. Photo: John Grobler

SELECTIVE PROSECUTION

What was noticeable about the abalone cases that made it to court was that only the professional poaching syndicates – but none of The Number-related gangs – were being fully prosecuted thus far.

This suggested that selective prosecution was used to force the professional poachers out of business in favour of the Cape Flat gangs’ abalone-for-drugs model – while leaving the Chinese buyers alone.

This confirmed a long-standing accusation from the DA that the ANC was using fisheries policy to deny local fishing communities legal access to their only natural resource.

By forcing increasingly impoverished local communities into the arms of organised crime by resorting to lawlessness, the ANC was trying to politically destabilise the Western Cape, said DA MP Beverley Shäfer.

This accusation was borne out when the poorest community in Hermanus, situated between Hawstone and Gansbaai, rioted and burnt down several houses and a community centre. The incident came shortly after the arrest of DAFF officials and members of The Numbers in the Overberg area.

On March 28 2018 City Express newspaper broke a story showing that the newly elected ANC secretary general Ace Magashule’s daughter, Thoko Malembe, was a partner in Unital Holdings, which was handed a contract to construct 1,050 low-cost houses in the Free State under Magashule’s premiership.

According to Unital’s share register, Malembe’s Chinese partner is none other than Jiangliang Li, the same person who, it is believed in absence of official DAFF confirmation, is the new owner of Port Nolloth abalone farm and who in January 2018 was arrested for laundering poached abalone through the Port Nolloth plant.

“Jieyan” is the Cantonese version of the Mandarin name Jiangliang – indicating that “the old man” of 29 Geelhout Crescent, the Chinese abalone boss, may have been indirectly in business with one of the ANC’s most powerful officials.

Funding for this investigation was supplied by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project