04 Feb Dynamic data discovery: The future of detecting wildlife cybercrime

Being able to identify transactions involving restricted species, and conversations happening about them, will assist law enforcement in the fight against wildlife trafficking. Roxanne Joseph reports

Technical process: The Dynamic Data Discovery Engine is designed to build as comprehensive a picture as possible of how, where and when vulnerable plants and animals are transacted over the internet. Photo: Provided

The internet is used to trade endangered animals, plants and their parts, and more broadly hosts communities and subcultures where this trade is normalised, routine and unchallenged.

There are numerous law enforcement agencies and organisations working to ensure that wildlife trafficking is identified, prevented and prosecuted at every opportunity, but with almost complete anonymity, easy access and seemingly endless variety, the internet makes this even more difficult to do.

Detecting Online Environmental Crime Markets, a report released in January by the Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime (GI), introduced an innovative tool called the Dynamic Data Discovery Engine (DDDE). It is designed to build as comprehensive a picture as possible of how, where and when vulnerable plants and animals are transacted over the internet.

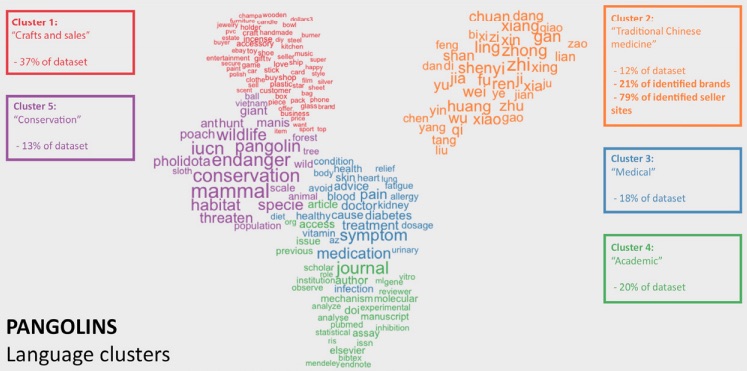

If you were to type “claws”, “skins” or “horns” into a search engine, you would be met with too many results to sort through. The DDDE attempts to solve this by giving you results that contain only illegal transactions, or discussions related to restricted commodities.

For sale: When we searched for ‘ivory for sale’ (based in South Africa), Google pulled up a whopping 1.2-million results. These results do not necessarily indicate illegal activity, and would need to be manually collected and narrowed down to begin to get a picture of ivory for sale online. Photo: Provided

To see what the DDDE was capable of, researchers Carl Miller, Jack Pay and Josh Smith trialled the tool across three case studies: orchids, pangolins and ivory. The intention was to identify as many URLs (the address or link to a page available online) as possible, and as precisely as possible, that were engaged in either the transaction of the commodity, or conversations about them**.

Case study #1: Orchids

Orchids were chosen as the first case study to test the initial data collection and analysis strategies of the tool. Researchers chose to focus on 14 websites (spanning more than two dozen languages) that are known to sell restricted species of orchids, and they identified words and phrases related to their sale.

They then conducted a process of elimination, trying to narrow down the results to contain as many relevant URLs as possible. Finally, they divided this into categories to determine which references were sales and which were simply mentions containing the word “orchid” and related keywords.

The orchid case study collected nearly 122,000 web pages from approximately 3,300 sites:

- Just over 1,000 were pages on eBay that mentioned a restricted species of orchid;

- These orchids were being sold by 10 separate vendors in the United Kingdom, United States, Germany, China, Malaysia and Thailand; and

- A further nine different websites selling restricted orchids were also discovered.

Test case: Some orchids can fetch tens of thousands of dollars. Once, in an offline auction, a rare orchid sold for $150,000. TRAFFIC, a wildlife trade monitoring network, found that tens of thousands of flowers are traded illegally across international borders every year. Photo: Pixabay

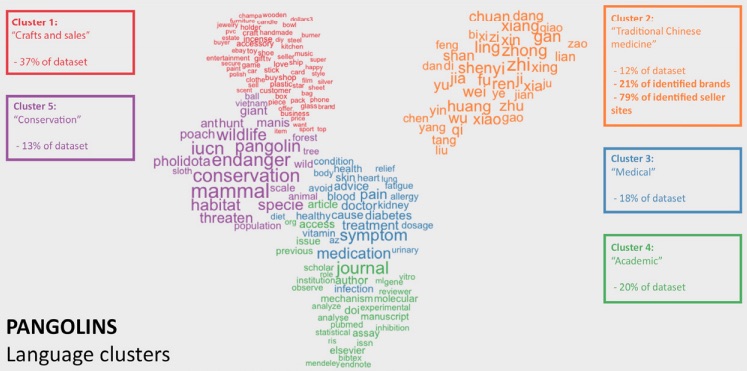

Case study #2: Pangolins

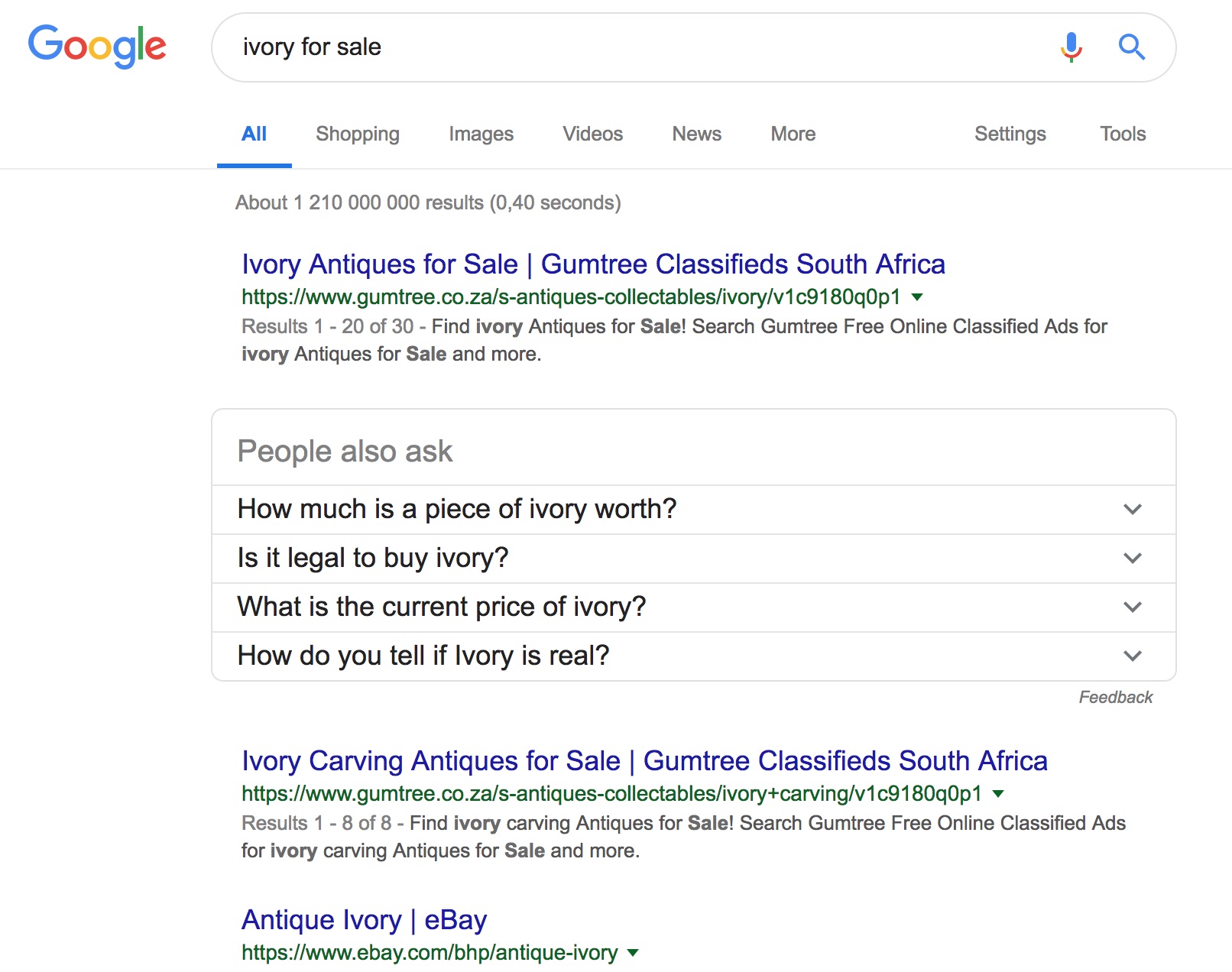

The second case study looked at the illegal sale of pangolins, and allowed for a smaller, more precise dataset. This is because pangolins make up approximately 20% of all wildlife trafficking.

Researchers started by creating an initial dataset, which they then narrowed down to results that only contained keywords pertaining to the illegal sale of pangolins and their scales, which are a popular ingredient in traditional Chinese medicine.

The pangolin case study gathered nearly 40,000 URLs:

- 5, 000 of them were found to be relevant to the transaction of pangolins; and

- Over half of these sites recommended or discussed the use of commodities containing pangolin parts in the context of traditional Chinese medicine.

Scales for sale: Pangolins are the world’s most trafficked mammal, with an estimated 10,000 to 100,000 poached each year. It is impossible to say how much of this takes place online, but with increased internet access this is likely growing. Photo: Provided

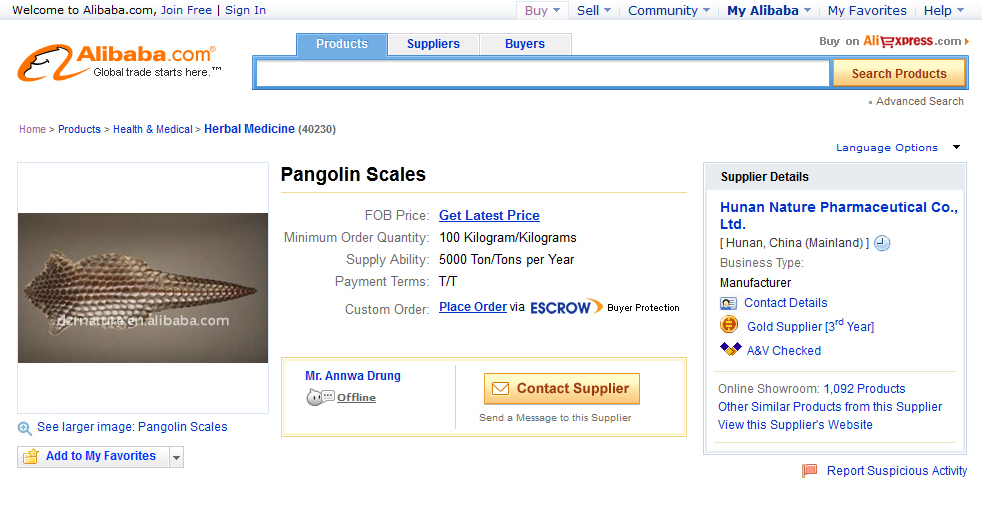

Case Study #3: Ivory

The main focus of the ivory case study was to improve the ability of the DDDE to discover larger quantities of data more automatically. A series of web searches were made using the keywords and each of these pages was then put through a process called “crawling”. This is the use of computer programming to browse the internet in a methodical, automated manner.

Within this case study, the data was put through a rigorous set of processes, with the aim of creating a more precise dataset. Distinguishing between legal and illegal ivory, and between ivory and other forms of horn, bone and teeth was a significant challenge when performing this analysis.

The ivory case study found more than 45,000 URLs:

- Nearly 8,000 of these were related to the online sale of ivory;

- 40% contained more general commentary about commodities containing ivory;

- Almost 30% contained descriptions of ivory-related products; and

- Just over another 30% were related to the sale of ivory.

Legal vs illegal: Ivory is one of the most sought-after commodities, but it is often difficult to distinguish the illegal sale of ivory from the legal. Photo: Conservation Trust

A limited, but powerful tool

Throughout these case studies, it began to emerge that the DDDE process was identifying not just individual websites, but in fact communities of websites that shared common vernaculars and interests, and that may be explicitly linked to one another too.

Researchers took the data that the tool produced and attempted to map different communities. In doing so, they hoped to provide a different way of differentiating between relevant and irrelevant activities and secondly, to distinguish between the different kinds of relevant activity that the DDDE found.

The data that is emerging from this tool is ground-breaking, and while there are limitations initially, the Global Initiative and its researchers have created something that will learn from its own processes, and become more accurate over time.

Being able not only to identify transactions involving restricted species, but also conversations happening about them, will inevitably assist law enforcement in the fight against wildlife trafficking. However, until the process has been more refined – and the data becomes more reliable and effective – researchers need to interrogate and conduct their own analyses on the information made available by the DDDE process.

** While the DDDE was able to collect more results than could be done manually, wildlife trafficking is an extremely complex issue, consisting of many legal, cultural and moral nuances. The results from the tool did not include only illegal examples; given the large number of results returned, it is likely that some of these were legal.

• Use our #WildEye geojournalism tool to track Europe’s role in the international illegal wildlife trade