24 Aug Confessions of an ivory poacher

Oscar Nkala talks to a jailed Zambian elephant poacher about the structure, financing and operations of cross-border smuggling gangs

Another bust: 13 elephant tusks, a hunting rifle and dried elephant meat abandoned by Zambian poachers in Zimbabwe’s Hwange National Park on August 11 2018. Photo courtesy Bhejane Trust

Zambian national Witness Katongo (not his real name) is an unhappy inmate of Khami Maximum Prison near Bulawayo, the second largest city in Zimbabwe.

Taken to the high-security prison after receiving a 14-year jail term for three counts of attempted murder and the illegal possession of nine elephant tusks in March 2016, Katongo considers himself lucky for he has lived to tell his story.

“Most Zambian poachers who venture into Zimbabwe are shot and never live to tell the tale. I am very lucky to be alive, never mind the maiming. I know many who were buried as paupers here because their families never got to know of their deaths,” he said.

Narrating the events leading to a gun-battle that left him with a stitched-up right leg and an amputated left leg, Katongo said he was leading 14 Zambian poachers back home from Botswana through the Hwange National Park in Zimbabwe.

The group was returning from a nine-day poaching expedition in the Pandamatenga area of northern Botswana. They were driven by urgency to meet the dug-out canoes that would transport the men and ivory across the Zambezi river to safety in Zambia.

Katongo was the gang’s “principal force protection” officer, armed with an AK-47 strapped to his back, and two hunters with .303 rifles made up the rest of their defence unit.

“It was still dark as I led the group in single file through the forest. It was raining heavily, and that worried me because it made for poor visibility,” he recalled. “Suddenly what I had thought was a shrub materialised into a soldier right in front of me. Two other ‘shrubs’ rose on the left, erupting into a clutter of gunfire.

“Before I could unsling my rifle, I was cut down by a hail of bullets that nearly demolished one leg. The other guys returned fire briefly and took to their heels with the rest of the group. In the melee, a porter dropped a bag with eight elephant tusks. I was arrested with a 16-year-old boy who secured his freedom by selling out to the police.”

The escapees included two porters who made off with bags containing 16 more elephant tusks, all sourced from Botswana. Katongo began serving his Zimbabwean jail term in mid-2017 after trials that left him angry and surgery that left him with an amputated leg.

“I am not angry because I was jailed,” he said. “Every poacher expects that to happen anytime. I am angry because I am here, yet I did not commit any crime in Zimbabwe. I was only passing through from Botswana. I told this to the police, but they would not listen.”

In prison, the ex-Zambian soldier claims to have turned to Christianity and “found God”. Visited at Khami prison on July 30, he opened up about the structure, financing and operations of a Zambian cross-border poaching gang.

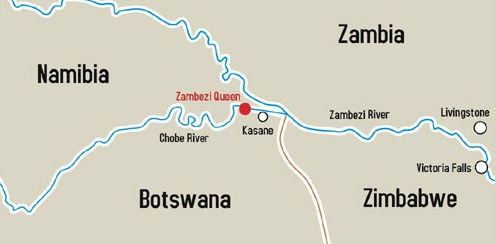

Cross-border trade: Zambian gangs use two well-known smuggling routes to transit through Zimbabwe to Botswana

Smuggling routes

According to Katongo, Zambian poaching groups going to Zimbabwe and Botswana recruit operatives from villages around Simonga, a poor Zambian fishing community located across the Zambezi from the Victoria Falls.

“The marksmen, weapons and force protection guys are usually former or serving soldiers and policemen. The trackers, guides and porters come from Simonga and other villages on the Zambezi.

“Every November a local businessman based in the city of Choma returns to the villages to recruit poachers. He brings cash, food, cellphones, multiple sim cards, AK-47s, hunting rifles and ammunition. The marksmen recruit the porters, couriers and people to run communications between the gang and the syndicate,” Katongo narrated.

From places like Simonga, the gangs cross the Zambezi into Zimbabwe in dug-out canoes hired from locals. They then use two well-known smuggling routes to transit through Zimbabwe to Botswana.

“With the help of Batswana, we targeted elephant herds outside reserve areas. It could be a month before the hunting party returned to Zambia,” Katongo said.

Since joining the Simonga-based poaching gang in 2011, Katongo said he had poached elephants in the Kazungula, Kasane, Pandamatenga and Nata areas in Botswana. The Zambian poaching gangs had adapted to overcome the shoot-to-kill policy practised for years by the Botswana Defence Force (BDF), he said.

“In Botswana there are more elephants outside the protected areas than in. The BDF may be good, but the elephants are too dispersed and highly mobile in the rainy season. So it becomes impossible to protect all herds. By splitting up into small groups, we would stalk and shoot for days before returning to Zambia,” he said.

In Botswana the poachers either stay in the bush, shifting camps daily to avoid detection, or are accommodated by Batswana accomplices.

Suspected Zambian and Batswana elephant poachers exit the Maun Magistrate’s Court in February 2018 after their first appearance in connection with the illegal possession of 11 elephant tusks. Photo courtesy The Voice (Botswana)

Poaching surge

According to statistics released by the Botswana Department of Department of Wildlife and National Parks in April, poaching has surged since 2016: at least 62 elephants were killed between April 2017 and April 2018, up from 42 in the same period between 2016 and 2017. The statistics also showed an increase in the trafficking of elephant tusks, with 109 seized in 2017-2018, compared to 48 in the same period in 2016-2017.

Without specifying nationalities, the report said foreign nationals were the main culprits while Batswana were increasingly getting involved in poaching and wildlife crimes. Recently updated statistics from the department show 30 elephants were poached in the Ngamiland district between May and July 2018, with most culprits being foreign citizens.

According to investigations by The Botswana Gazette, Zambian suspects have been involved in cases involving at least 66 elephants tusks in Zimbabwe, Botswana and Namibia since August 2017.

Recent seizures include 13 tusks that were abandoned at a police checkpoint in Botswana by a suspected Zambian poacher in June. Fifteen tusks from Botswana were seized in July from suspected Zambian poachers after a gun-battle that killed one in Matetsi National Park, Zimbabwe.

Zimbabwean conservation organisation Bhejane Trust said when Botswana banned hunting in April 2014 it had “inadvertently invited” Zambian poaching incursions by ending security patrols along the border with Zimbabwe. The trust works with the Parks and Wildlife Management Authority of Zimbabwe (ZimParks) in various conservation, anti-poaching and rangeland conservation initiatives.

“When Botswana stopped hunting, it effectively abandoned [patrols in] vast chunks of land adjoining the Hwange and Matetsi [national parks] areas of Zimbabwe. This was an open invitation to Zambian poaching gangs who had had it tough in Zimbabwe, with many of their key members killed in contacts with game rangers,” said the trust’s co-founder and lead conservationist, Trevor Lane.

With safer areas to operate in Botswana, Zambian poachers by-passed Zimbabwe to enter Botswana in the Kazungula border region and link up with Namibian accomplices.

“They then traversed the Chobe [river] into the back areas where they could shoot elephants. Some of the gangs would take a short-cut through Zimbabwe, and a couple paid the price by encountering Zimbabwean game rangers, leaving their ringleaders killed and all their spoils and ivory lost,” he said.

Oscar Nkala is an Oxpeckers Associate. This article also appeared in The Botswana Gazette here

• Read more stories on poaching links in Botswana and Zimbabwe