30 May Battle for the green heart of the West Coast

Does the world need more phosphate? Is it worth digging up a biodiversity and heritage hotspot for fertilizer? Marie-Louise Antoni investigates plans to mine on the doorstep of the West Coast National Park

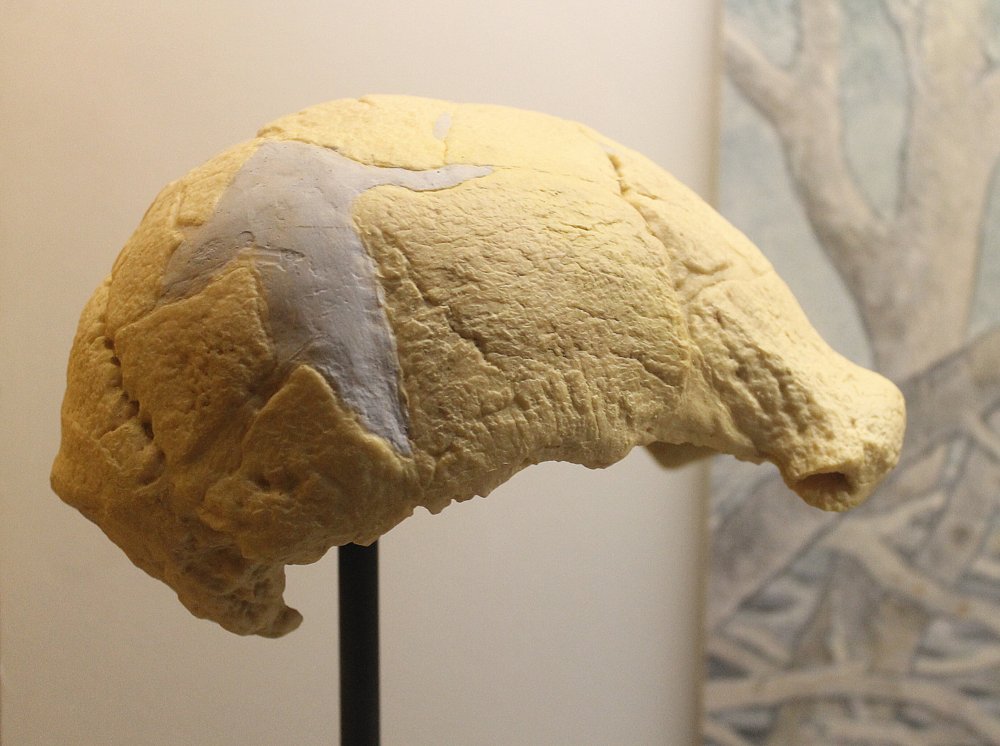

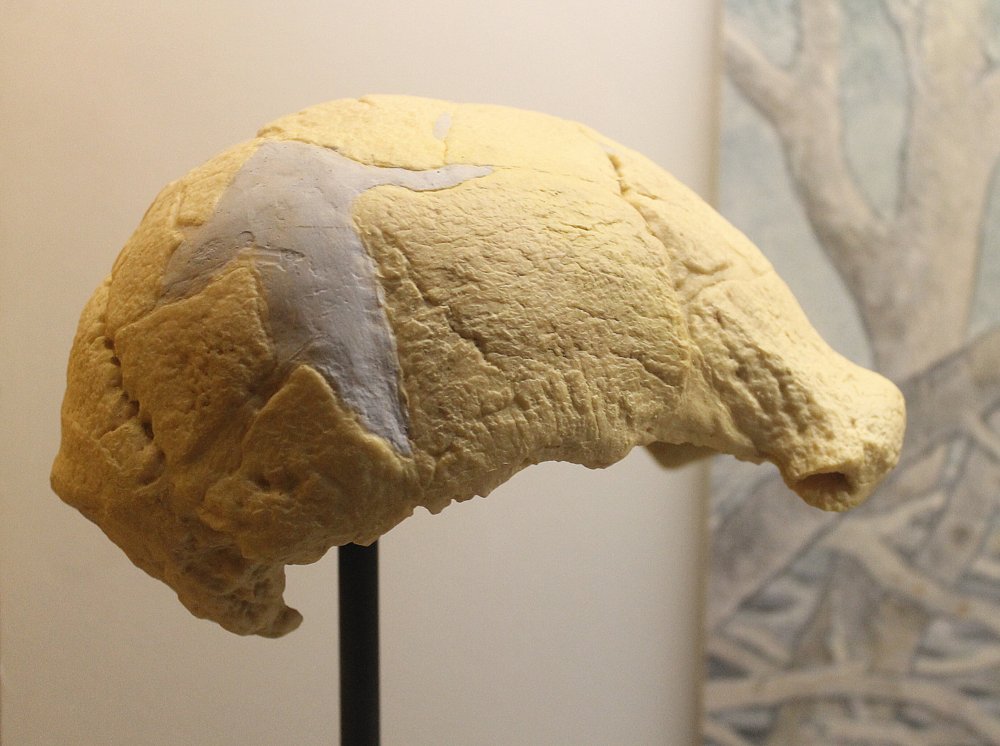

The fossilised human skull known as the Saldanha Man, dating between 700 000 and 400 000 years ago, brought international attention to the area

The company already holds prospecting rights, but obtaining mining rights will be a battle, because the minister of mineral resources can turn down or limit applications that affect critical biodiversity, heritage, or areas of hydrological importance. The application is challenged by all three.

But the company is confident about its prospects. “From a legal standpoint, we believe it will be compliant. We’re legally within our rights to proceed with the application,” said Michelle Schroder, metallurgical manager and spokesperson for the mine.

Tourism mecca

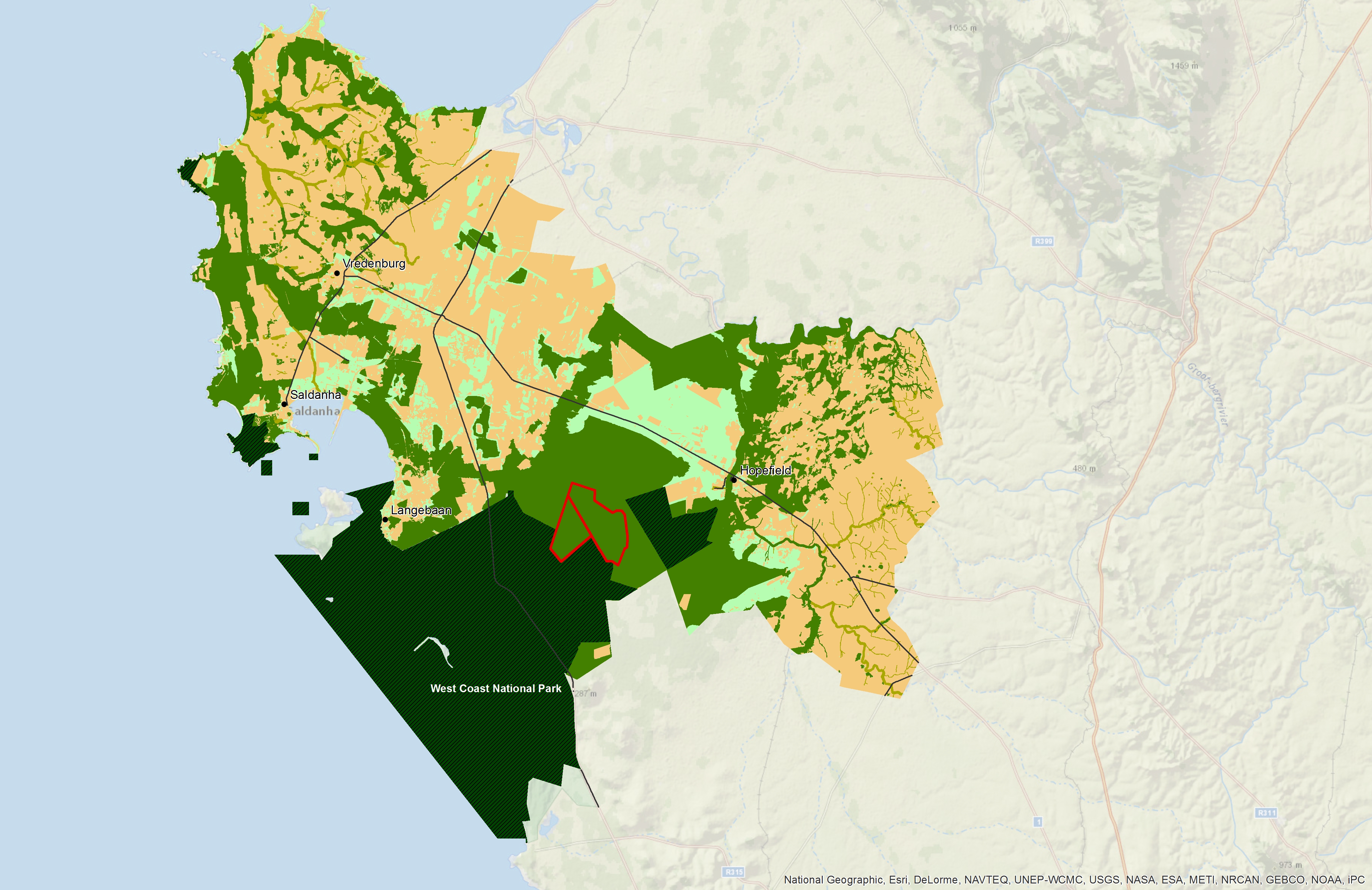

The site falls within the biosphere reserve and lies on the West Coast, just over an hour outside of Cape Town. An aerial view shows an expanse of green pooling out from the Langebaan Lagoon, spreading inland to the town of Hopefield about 30km away.

Much of this land belongs to the park, world-renowned for its flora and birdlife, and the lagoon is an international kite-surfing mecca and vital to tourism. Every year, the park attracts more than 200 000 tourists, and creates 20 000 permanent jobs, indirectly sustaining about 100 000 people.

The proposed mine lies in the very heart of this, on the park’s buffer zone, within a critical biodiversity area (CBA). About 400ha will be actively mined, while another 220ha have been set aside for further development. And the deposit is mammoth – the second largest in the country – with ore tonnage weighing in at around 90 million.

The local economy has traditionally been supported by more sustainable industries, like agriculture, fishing, conservation and tourism, and the site falls well outside the Saldanha Bay industrial development zone.

The property is zoned for agriculture and was previously a private nature reserve, and it separates two portions of land belonging to South African National Parks (SANParks). It was considered vital to the park’s expansion strategy, being earmarked for a biodiversity corridor, and is why SANParks tried to buy it over the years.

The region is generally water-scarce, and the company will be using groundwater, some of which will be pumped back into the system. There are two important aquifers in the area, and one is believed to seep into the lagoon, which is internationally protected for its wetland ecosystem as a Ramsar site.

“We’re looking at water very closely with the department,” said Schroder. “We’re trying to understand what our potential impact might be and how to mitigate it.”

The red outline shows Elandsfontein’s prospecting area. The green shades indicate protected areas, critical biodiversity areas and regions of ecological support

Middle and Early Stone Age tools of more than a million years old have also been found, and the site is of global significance. Dr David Braun, who currently holds the research permit for the archaeological site, noted in a study that the area is “one of the richest sites of its kind in Africa”.

The mine’s infrastructure will also require waste treatment facilities, a slime dam, power lines, as well as an 18km pipeline to the port in Saldanha. This will run over neighbouring properties, many of which are also CBAs.

But the company says the deposit is strategic, and although there isn’t a current shortage of phosphate, it says global demand is rising. Phosphate is used in agricultural fertilizers, and the company says it’s critical to food security.

Between 300 and 400 jobs will be created, and 80% of the labour force will be locally sourced. The current life of the mine is estimated at 15 years. The company says it will develop skills, and it’s also looking at bursary schemes for science students at various tertiary institutions.

“We want to move away from the perception that mining is a filthy, dirty thing,” said Schroder, adding that the company is planning significant offsets and rehabilitation. “There will be better conservation in the area if we mine than if we don’t.”

There will be a 10:1 offset ratio, Schroder said. “Environmental impact has been a critical driver in our decision-making, and we’ve employed the best experts. The net effect is positive.”

Letter of the law

Asked whether the application was a difficult one, Philip le Roux, technical manager for the mine, said: “No, not at all. We’re following the letter of the law. We already have prospecting rights and have also received departure from the municipality.”

But has the company done enough to inform those it says will benefit from the mine, the very same people who, should the operations not go according to plan, will be saddled with the consequences?

Le Roux believes it has. “We followed the law. We advertised,” he said. “We’re working with all organs of state and government departments, as well as different organisations. We’re saying, ‘Please come and monitor us so that we can comply.’”

The current process falls under the Mineral and Petroleum Resources Development Act and Le Roux said the company is bound by the department of mineral resources’s regulations. These state that companies must consult stakeholders and submit their first scoping report within 30 days of notification.

“We were expecting a response from the department in January, but it came through in December,” he said.

However, documents show that the company submitted their application on December 9. By law, the department has 14 days to reply, which means the company would have had a response by around Christmas Eve latest.

In reality, though, the department responded the very next day. But Elandsfontein Exploration and Mining only published its notices on December 19, more than a week later, and well into the holiday period. These notices were placed in two newspapers, alongside a telephone number that did not work.

Spectacular flower displays and kite-surfing are among the attractions that draw more than 200 000 tourists a year, creating 20 000 permanent jobs and indirectly sustaining about 100 000 people in the region

Technical fault

The mine’s environmental consultant, Olivia Braaf, was notified of this error. She apologised, saying it was a technical fault, but by January 8 it still did not work, while the deadline for public comments to be included in the first submitted scoping report fell on the same day. Braaf still maintained that the process was legally compliant, and that contact could have been made via email, post or fax.

At public meetings held in Hopefield and Saldanha on January 6 and 8 respectively, several stakeholders complained. One even asked for a letter be written to the department to request an extension, but instead, project holding costs were cited. However, the company did say that concerns would be raised with the department.

Meeting minutes submitted to the department on January 22 do not mention these discussions, however, nor was a written objection, dated January 20, included in the report. In fact, the report specifically states that no objections were made.

Braaf said the written objection did not apply to that stage of the process, but adds that objections have now been included in the final scoping report.

Furthermore, in Elandsfontein’s submission to the department, the company states it intended to hold two sets of public meetings during the scoping phase, while only one set was held. A further environmental impact assessment meeting was scheduled for May, but this has not yet taken place.

“This is just the start of the process,” said Braaf. She added that the department’s guidelines state that consultations do not end after 30 days.

“In fact, further in-depth consultation is required to more substantially inform the environmental impact assessment and environmental management programme. There will thus be ongoing consultation through the process with interested and affected parties and key stakeholders.”

Public participation

Tracey Davies, attorney at the Centre for Environmental Rights, said public participation in mining right applications is extremely important. “The process takes on an even more significant role when the mining is likely to affect biodiversity priority areas”, she said.

Davies referred to the 2013 Mining and Biodiversity guideline. “The guideline makes it clear that in such cases there may be a greater number of stakeholders interested in and concerned about the proposed activity.”

The Consultative Forum of Mining in 2002 created a set of public participation guidelines, sponsored by the Chamber of Mines. The forum agreed that consultations don’t only benefit the public. When properly conducted, they also benefit mining companies, enabling them to prove due process, which adds to their credibility and is ultimately less costly.

And while there’s no blueprint process, the guideline repeatedly uses the example of “an open cast mine bordering a national park” as an example of where public sensitivity would be high.

It also says that public sensitivity heightens with issues such as water catchments, archaeology, and areas with a sense of place, such as conservancies, nature reserves, national parks, Ramsar sites and heritage sites, and particularly for new developments in previously undisturbed areas.

These guidelines (explicitly confirmed by the 2013 Mining and Biodiversity Guideline), include a public sensitivity matrix (ranging from “very low” to “very high”). Because of the described tangle of factors, the mine’s application could fall under the “high” to “very high” categories.

This would mean extensive public consultations, media releases and radio announcements, and between 200 and 400 stakeholders should be identified (or, depending on its classification, between 1 000 and 3 000). Currently, the company’s publically released database contains just under 200, but around 30 of these names appear twice or even three times.

Conscious decisions

“We looked at the guidelines, but at the end of the day, decisions are made by law,” said Le Roux. “In my opinion, we’ve sat down with the best experts. We’re making decisions and 90% of them are based on environmental reasons, for the least impact, and to the benefit of everybody.”

Schroder said, “We’re aware of the guidelines, but have not taken them into account at this stage,” but added, “we believe we can mine responsibly. We’re taking conscious decisions; decisions that are not necessarily cost-effective but that are the most environmentally safe.”

The company has now released its scoping report, and the deadline is June 2. It will submit its second report – the environmental management programme report – June 10. This means these two phases were run almost concurrently.

However, the guidelines specifically recommend two distinct phases, so that stakeholders can make sure their concerns are addressed. The guidelines state that stakeholders “contribute essential local knowledge and wisdom”, and these processes help to “clarify the degree to which they are willing to accept or live with the trade-offs”.

Although these guidelines are soft law, and as such difficult to enforce, proper consultations would go a long way in demonstrating good faith. It would also give more credence to the company’s slogan of “Putting Nature First”. – oxpeckers.org

#MineAlert: Find out about mining projects near you, and register for alerts, here

Related links:

• West Coast mine tests new authorisation system

• SA’s water bubble