22 Jun Climate change: How will South Africa act?

South Africa is party to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, and has to produce a plan of action before the end of the year. Steps taken so far have not been encouraging, writes Ruth Kruger

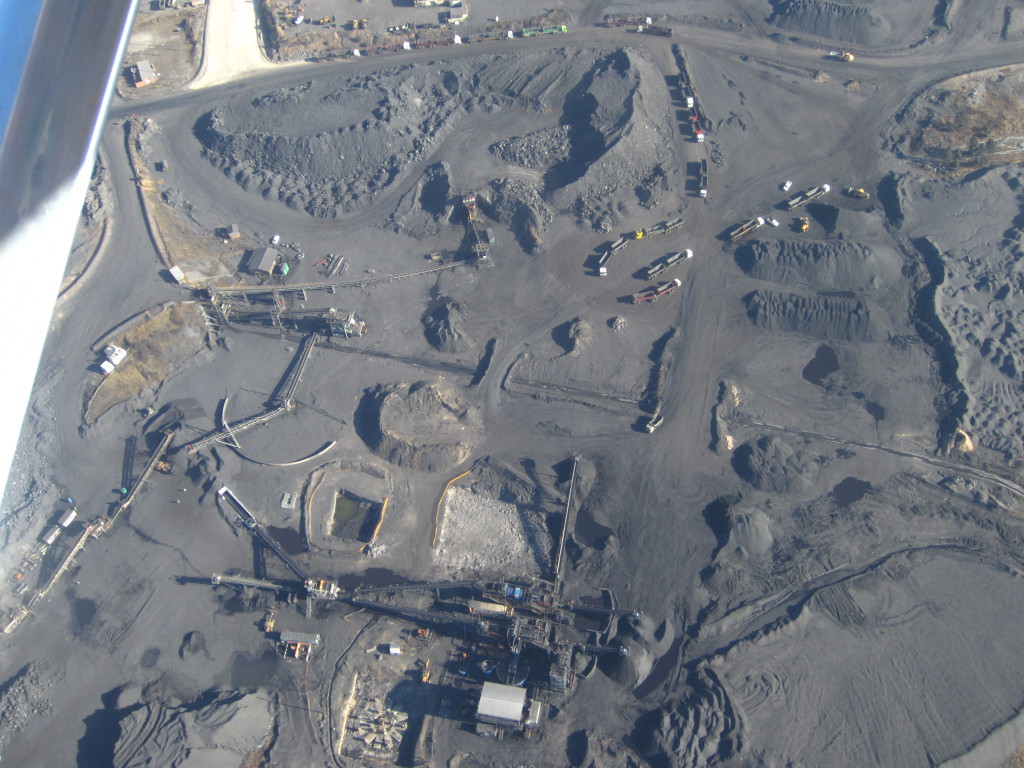

Coal trucks collect their loads on the Mpumalanga Highveld, where most of South Africa’s coal is produced. Photo: Tracey Davies, CER

The Department of Environmental Affairs is preparing a plan of action that will be submitted to the United Nations before its next climate change meeting in Paris in December 2015. There are high hopes for this meeting, which is expected to lead to a legally binding agreement tying all countries into climate change action.

The agreement will be based on national plans of action and climate change commitments, called the Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs). In March the Department of Environmental Affairs gave an update on the development of South Africa’s INDCs, and announced the intention to submit these by August or September.

Will the INDCs address South Africa”s climate change responsibility?

David Hallowes, an independent researcher, is not hopeful: “South Africa is a party to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, so we have to produce INDCs. But the government is not going to offer more than they offered in the meeting in the Copenhagen agreement” – referring to commitments made during the Copenhagen summit in 2009

His expectations were confirmed at a briefing by the department to the parliamentary portfolio committee on environmental affairs on May 26 2015, which provided an update on South Africa’s national climate change response strategy. Judy Beaumont, deputy director general for climate change, stated: “South Africa is putting instruments into place to achieve a 34% and 42% reduction [of emissions] against business-as-usual by 2020 and 2025. That’s the Copenhagen pledge in terms of mitigation. It will be the focus of South Africa’s INDPs.”

So it seems South Africa will not move beyond what was promised in 2009. Beyond that, however, all we can do is watch the South African landscape for clues on the shape that the INDCs will take.

Minimum emission standards

In March, the national air quality officer granted the vast majority of postponements sought by industry of the minimum emission standards. The standards are a new tool which should have applied with effect from April 2015, and were designed to regulate the emissions of numerous dangerous pollutants, such as sulphur dioxide, nitrous oxides, hydrogen sulphide and particulate matter.

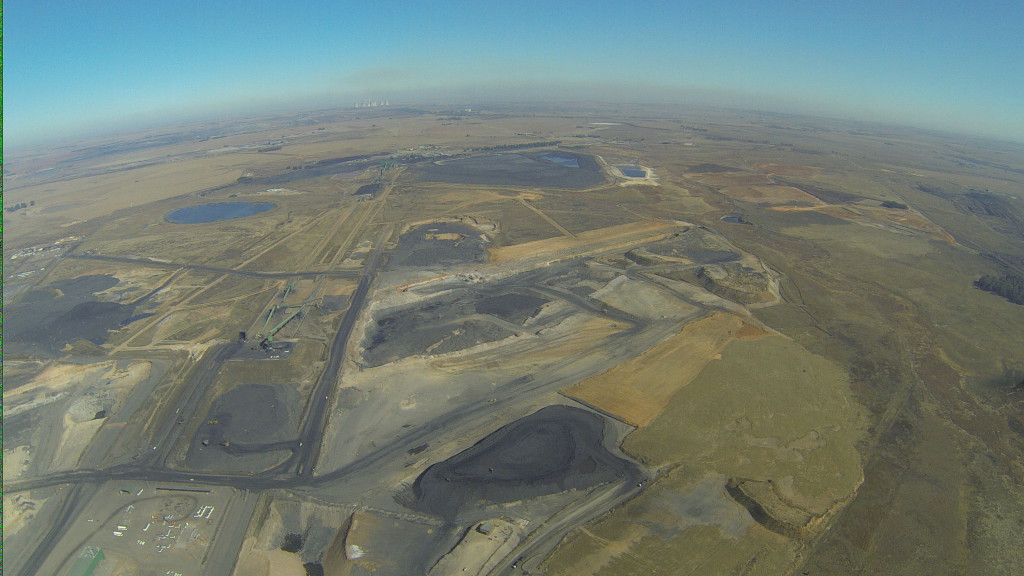

Energy production through opencast coal mining and coal-fired power stations has transformed the landscape on the Mpumalanga Highveld, and filled the atmosphere with smog. Each power station emits a toxic combination of SO2, NOx, particulate matter, and other pollutants. Photo: Melissa Fourie/CER

Since the Act came into force, there has been an assessment of the costs and benefits of its application every 10 years. The first assessment showed that for every dollar spent by industry to reach compliance, there was a saving of $25 on health. Now, a few decades later, $30 are saved on health for every $1 spent on compliance by industries.

South Africa”s minimum emission standards set an upper limit for the emission of various pollutants – first a limit that applies to all existing coal-fired power plants from April 1 2015, and then a stricter limit that will apply to these plants in five years’ time, from April 1 2020.

It is the first time a regulation of this kind has existed in South Africa, and the standards are still far more lax than standards in several other jurisdictions. Euripidou was involved in the negotiation of these limits, and believes they represented a compromise by civil society.

“It felt as though we were making a bigger compromise than industry. But we had to have a peg in the ground, and in that spirit we agreed to the limits,” he says.

If the standards are properly applied and enforced, though, they can be a valuable step towards ensuring the constitutional rights of all South Africans to an environment not harmful to health or well-being, and to have the environment protected.

However, according to Euripidou, that is not what is happening. “The minimum emission standards are not being respected, and not being applied the way they should be,” he says.

“The air quality legislation states that there should be no postponement of the standards unless an industry is in compliance with the national ambient air quality standards – which are significantly weaker than those recommended by the World Health Organisation. But that is not what is happening now.

“The minimum emission standards postponements have been granted. They are clearly political decisions, which contradict the intention of the Air Quality Act and our environmental rights in terms of section 24 of the Constitution.”

Industries have known of the impending application of the minimum emission standards at least since they were published in 2010, and several industrial giants, such as Sasol and Eskom, were intimately involved in their creation before that.

However, many industrial facilities – including Sasol’s operations in Sasolburg and Secunda, and all but one of Eskom’s coal-fired power stations – applied for postponement of the standards for at least five, and in many cases, 10 years. In fact, they first tried to be exempted from the standards entirely, but settled on postponement when the minister confirmed that exemptions were not legally permissible.

Rolling postponements

There is still the possibility, however, that the very same industries will apply for postponement again when their first postponement period is up, prompting fears that South Africa’s largest polluters will be able to avoid emissions standards forever, by simply receiving “rolling postponements” until the facilities are decommissioned.

“Rolling postponements are going to happen,” says Euripidou. “The only way we can resist this is to mobilise people. The sheer weight of public opinion will drive action, whether have a progressive government or not. If there isn’t the weight of public opinion, we will get nowhere. Government will do exactly as it wants.”

Smoking stacks of an Eskom power station. In the background is a human settlement, in close proximity to the power station and its air pollution. Photo: Melissa Fourie/CER

Pollution mitigation technology costs money, at least in the short term, says Hallowes. “Clearly it’s cheaper to emit carbon if you don’t put a scrubber on.” The “scrubber” is technology that reduces sulphur emissions.

The national air quality officer may have missed an opportunity to contribute to South Africa’s INDCs. Putting the minimum emission standards into place and enforcing the regulation could be an INDC in and of itself, particularly if INDC projects involving all climate-affecting pollutants are acknowledged, not just those that deal with carbon.

Carbon may be the most well-known of the emissions that impact on the climate, but it is not the only one. Many industrial pollutants interfere with climate in complicated ways, and the minimum emission standards would regulate and reduce these, so that its proper implementation would help to mitigate climate change.

If, however, these standards are toothless, governed by their own postponement clause, then South Africa stands to lose credibility and the minimum emission standards cannot be seen as an INDC.

For the moment, the minimum emission standards postponements have been granted. Reasons have been requested in terms of the Promotion of Administrative Justice Act, but have not been received. At the very least, the national air quality officer should commit to allowing no further postponements. This is essential for South Africa’s position in climate change negotiations, and also more immediately for the health and well-being of the millions of South Africans who are forced to breathe these poisonous pollutants.

Ruth Kruger is a volunteer for the Adopt-a-Negotiator team in the run-up to COP21 in Paris. This article was written in her capacity as programme officer at the Centre for Environmental Rights, with support from attorney Robyn Hugo, head of the centre”s pollution and climate change programme.