Local authorities work with experts to develop disaster risk plans.

Local authorities work with experts to develop disaster risk plans.

Fires, floods, drought, storms: climate change can worsen the effects of natural disasters across South Africa. Anina Mumm investigates projects that help to reduce the risk of future disasters, instead of simply reacting to them

When the Western Cape experienced its worst storm in three decades in early June, disaster relief teams were on stand-by thanks to the early warnings provided by weather services. Nevertheless, the storm caused several deaths, devastating fires in Knysna and other Garden Route towns, flash floods and other major destruction across the Western Cape.

In one municipality within the Ehlanzeni district of Mpumalanga back in 2012, the roofs of nearly 1,000 houses were blown off during heavy rains, leaving many residents without food and shelter. Disaster managers had to organise blankets, mattresses and collapsible housing, as well as new ID documents, birth certificates and school books.

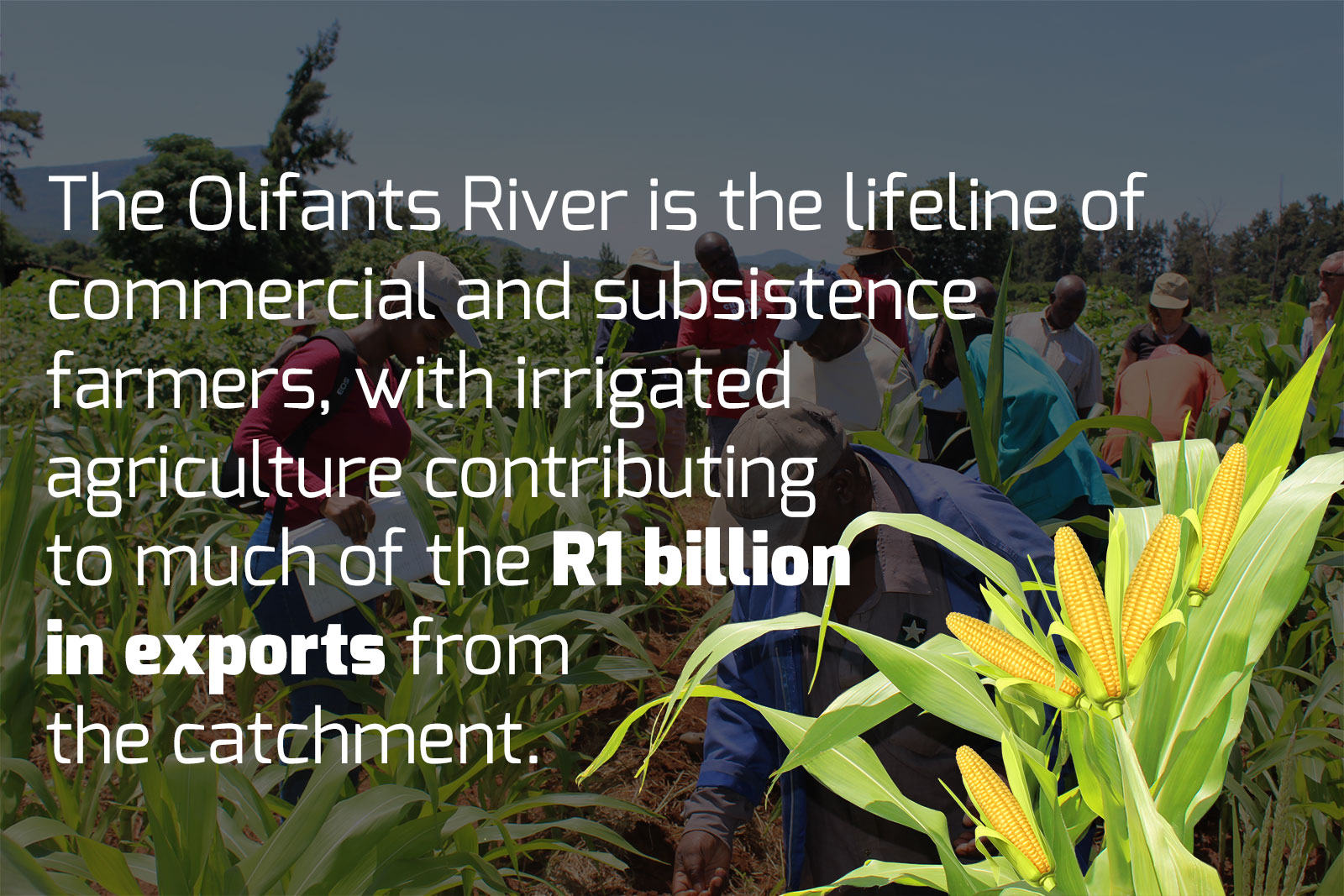

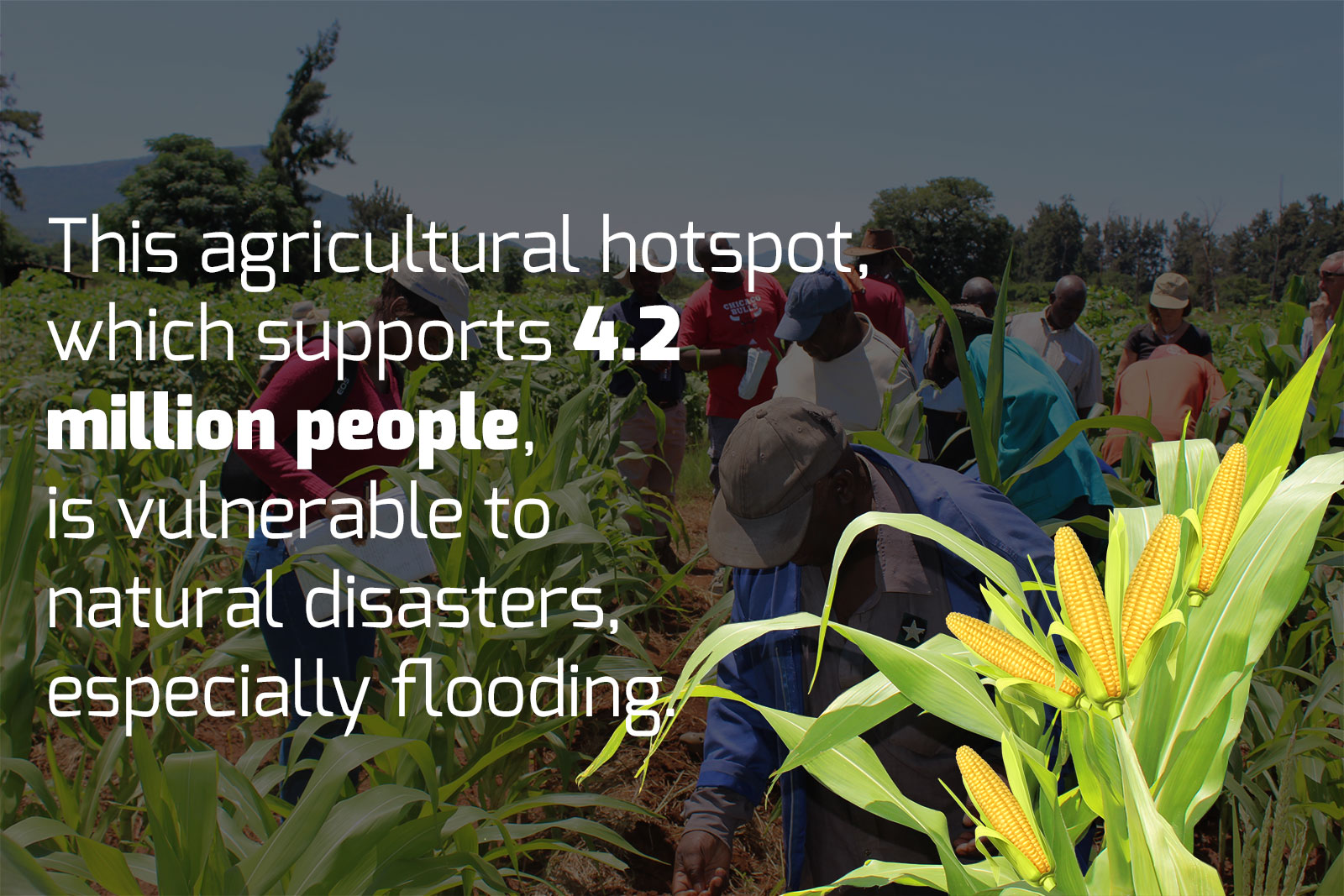

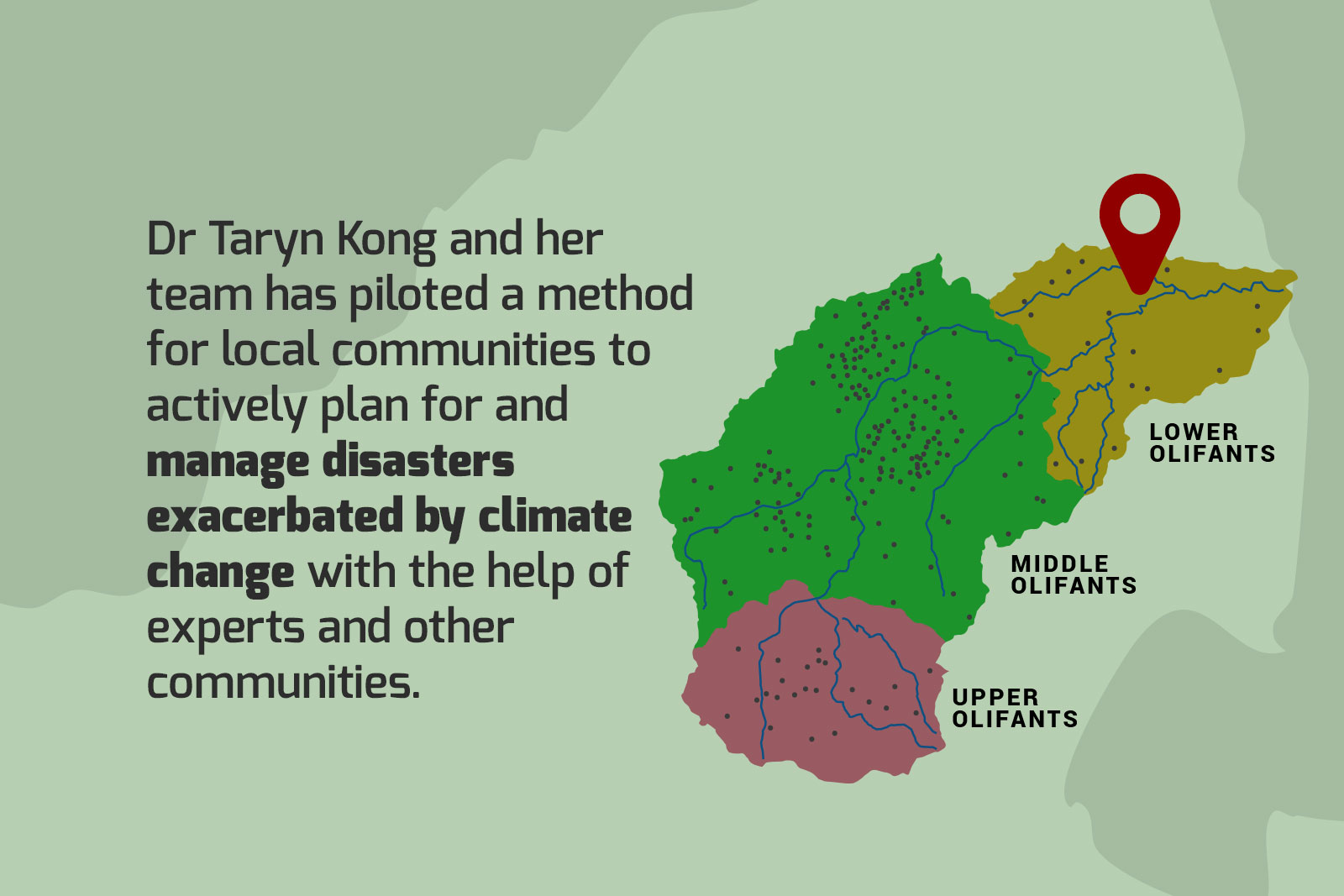

Ehlanzeni falls within the Olifants River Catchment, which is home to more than four million people and which supports major agricultural activities.

The Cape of Storms and the Olifants River Catchment region are both extremely vulnerable to natural disasters like flooding, and a changing climate exacerbates that risk. Local conditions – landscapes, politics, resources and capacities – may be unique, but there is one common thread: a mindshift is needed, from simply reacting to disasters, to reducing the risk of future disasters.

Communities, decision-makers, non-governmental organisations and scientists are searching for better ways to plan for and respond to disasters, but there is no one-size-fits-all template. Unfortunately, these efforts often happen in silos, with little communication or collaboration between groups.

Experts say authorities need to think about what happens before a flood as much as what happens after, and they will need to work together across municipal, district, provincial and even national borders to address these risks effectively.

Social learning and science

A grassroots approach that combines “social learning” and a scientific concept known as “systems thinking” (talking a problem from many different angles) may be what is needed to shift minds and policies to focus on disaster risk planning.

This is according to Dr Taryn Kong, a Climate Change Research Associate at AWARD, a South African NGO that has been working in the field of water resource governance and management for nearly two decades.

“It’s one thing for authorities to provide blankets after a disaster,” she explains, “but quite another to have asked before the rains, ‘why don’t we check if these bridges can accommodate a flood?’” To answer such a question, experts and decision-makers from different fields would be needed.

Hence Kong has been piloting a social learning model in three municipalities in the Olifants River Catchment over the past year as part of the USAID-funded RESILIM-O program. Social learning means bringing people of different expertise and experience together to learn from one another to solve problems, Kong says.

In the context of reducing flood risks in the Olifants River Catchment, she is essentially a matchmaker between scientists and other experts, local authorities and community members to enable municipalities to plan effectively for local climate change challenges.

Julesburg Agricultural Scheme members during an AWARD workshop on farming using agro-ecological processes as one of their farms.

Julesburg Agricultural Scheme members during an AWARD workshop on farming using agro-ecological processes as one of their farms.

Planning for floods

Kong has been piloting the social learning approach to disaster risk planning in Maruleng and Ba-Phalaborwa local municipalities, and the Mopani district municipality in Limpopo.

One of the experts Kong has called on to help in Maruleng is Professor Agnes Musyoki, an economic geography researcher based at the University of Venda. Musyoki has been working with communities in Limpopo for more than 20 years, specifically researching issues around climate change vulnerability.

LISTEN: “Bottom up is best to address climate change vulnerability” – Prof Agnes Musyoki

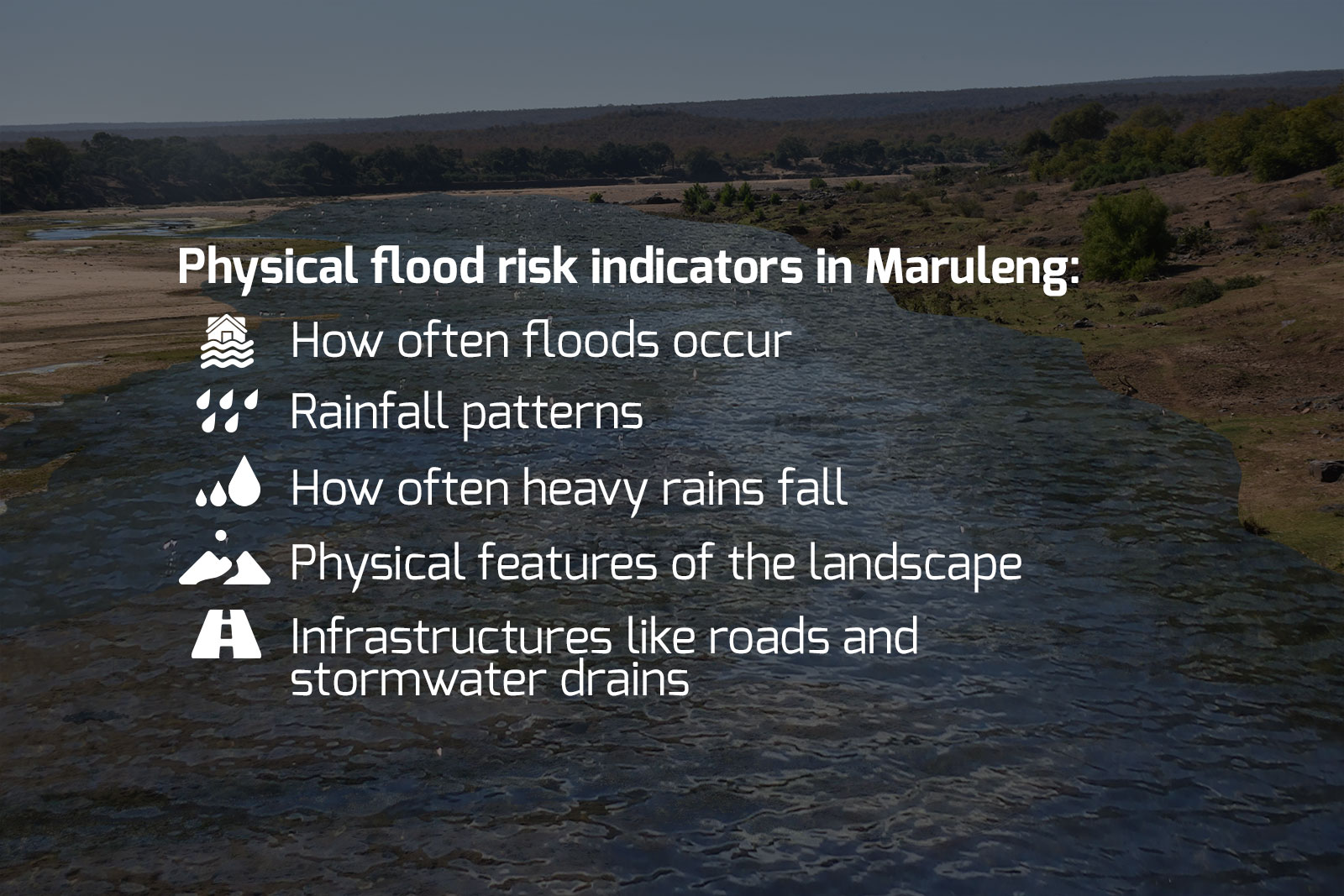

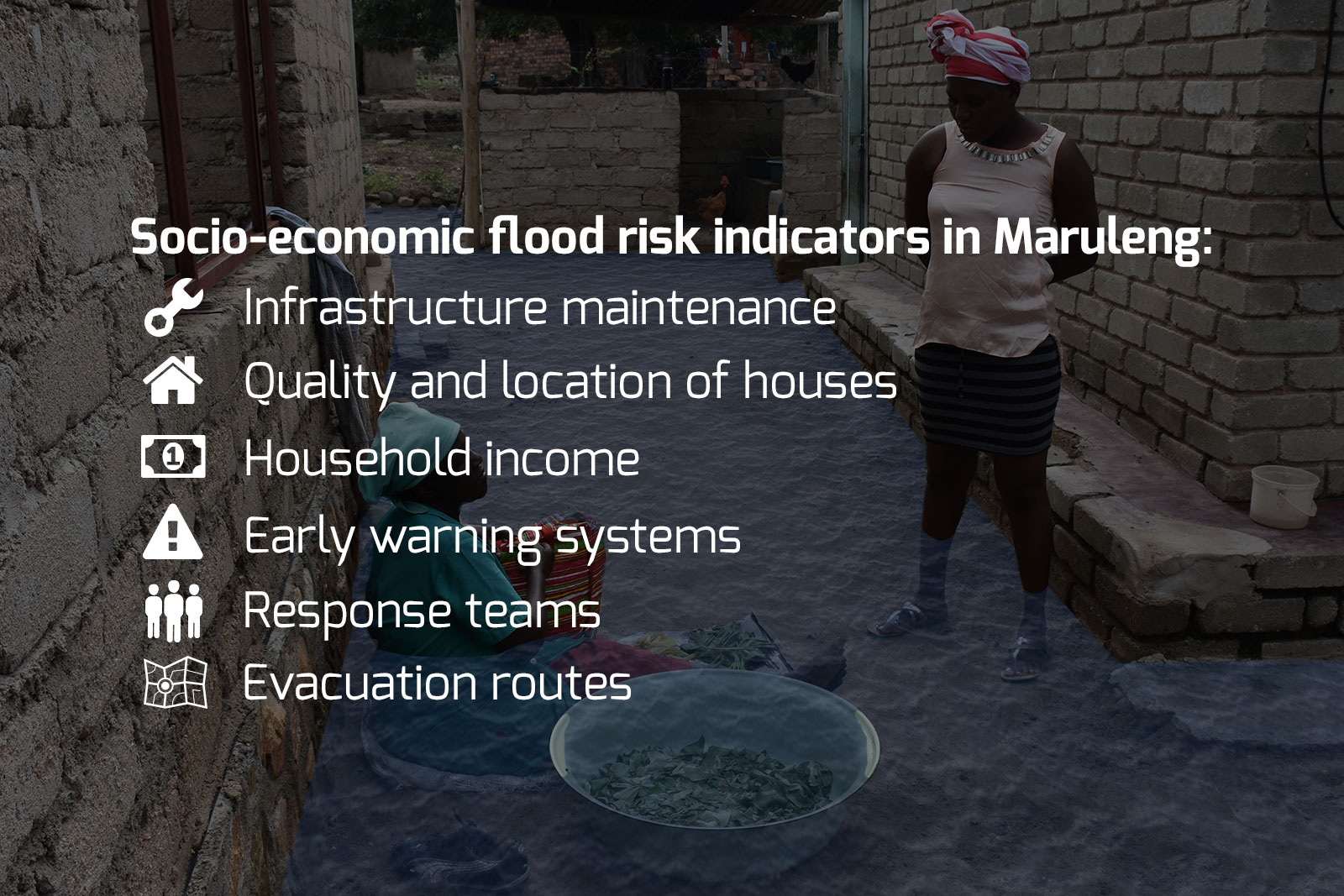

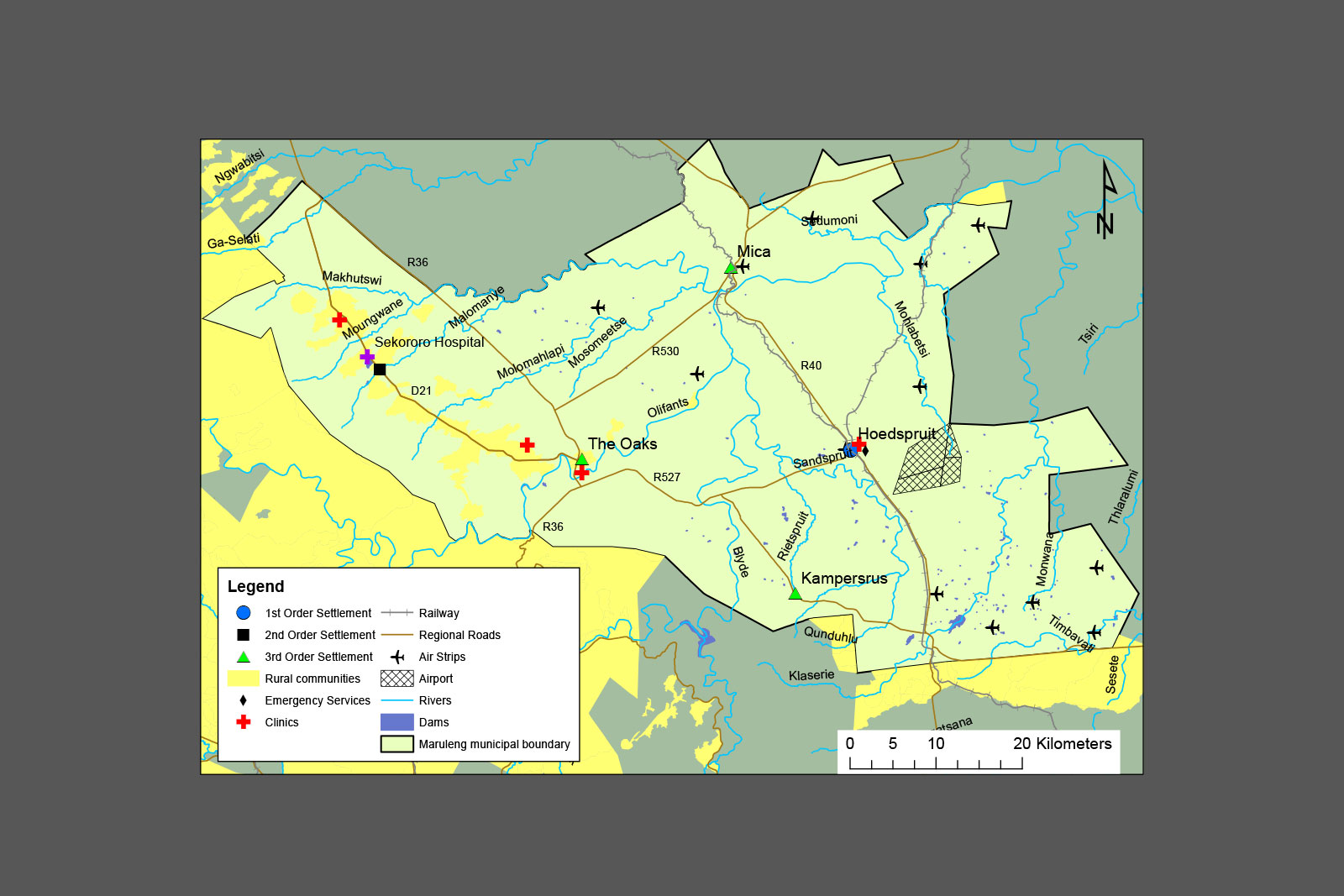

Musyoki, Kong and other experts are working with the Maruleng community to come up with locally relevant flood risk “indicators”, such as where evacuation routes are, the location of people’s houses and how often heavy rains fall.

A detailed analysis of these indicators helps local authorities better understand the different aspects of flood risk, and to plan for disasters in partnership with hospitals, residents and other concerned groups.

Kong says this approach is different to the current system where authorities rely on service providers to help prepare disaster management plans. At the local level, she says, disaster management “advisory forums” are often merely administrative, thus disaster manager can’t in reality draw on the expertise of these forums to support planning.

“Disaster management is cross-disciplinary,” says Kong. “In a rural setting the disaster manager must wear many different hats. It’s often just a side gig for him as he is busy with many other things. He could also come from a background of one particular discipline, but is now expected to work in this multidisciplinary field.

“It should be the role of the advisory forum to provide expert advice in different fields, but in some places there is no such forum, in others the forum may not work as a planning platform, and sometimes the advisors themselves don’t have enough capacity or skill.”

The national government relies on the National Disaster-Management Advisory Forum, but national policies do not always trickle down to address unique local circumstances effectively, Kong says.

The bottom-up approach, with communities on the ground directly participating in disaster planning, is the best way forward for local authorities, says Musyoki. She is an independent researcher who has been involved in the Olifants pilot project as well as many other climate resilience projects in the region.

National Government relies on experts to help plan for risks associated with climate change, including floods. The official structure for this is called the National Disaster-Management Advisory Forum. At the local level, advisory forums are often only administrative and decision-makers thus lack the right support and capacity to properly manage disaster risks.

For the Maruleng flood risk indicators, Musyoki and Kong worked with the local advisory forum and disaster managers to shortlist locally relevant indicators from known options.

LISTEN: “How we developed flood risk indicators for Maruleng” – Prof Agnes Musyoki

The Olifants River at Kruger National Park during the drought season.

The Olifants River at Kruger National Park during the drought season.

Julia Nyathi, one of the small-scale farmers AWARD works with from Finale village, cleaning some pumpkin leaves from her garden with her daughter.

Julia Nyathi, one of the small-scale farmers AWARD works with from Finale village, cleaning some pumpkin leaves from her garden with her daughter.

Each indicator was clearly defined by the group based on their combined experiences and knowledge, and the group had to select indicators realistically, for instance by considering whether the data behind an indicator would help identify hot spots for flood risk, or where the geospatial data might be sourced. Geospatial data is often incomplete or non-existent, and may require technical skills to analyse.

“This is social learning in the sense that we don’t just give you the indicators and say, ‘here, use this’,” explains Kong. “You have to decide for yourself. It is collective learning that brings about transformation in practices or systems. It requires people and relationship-building .”

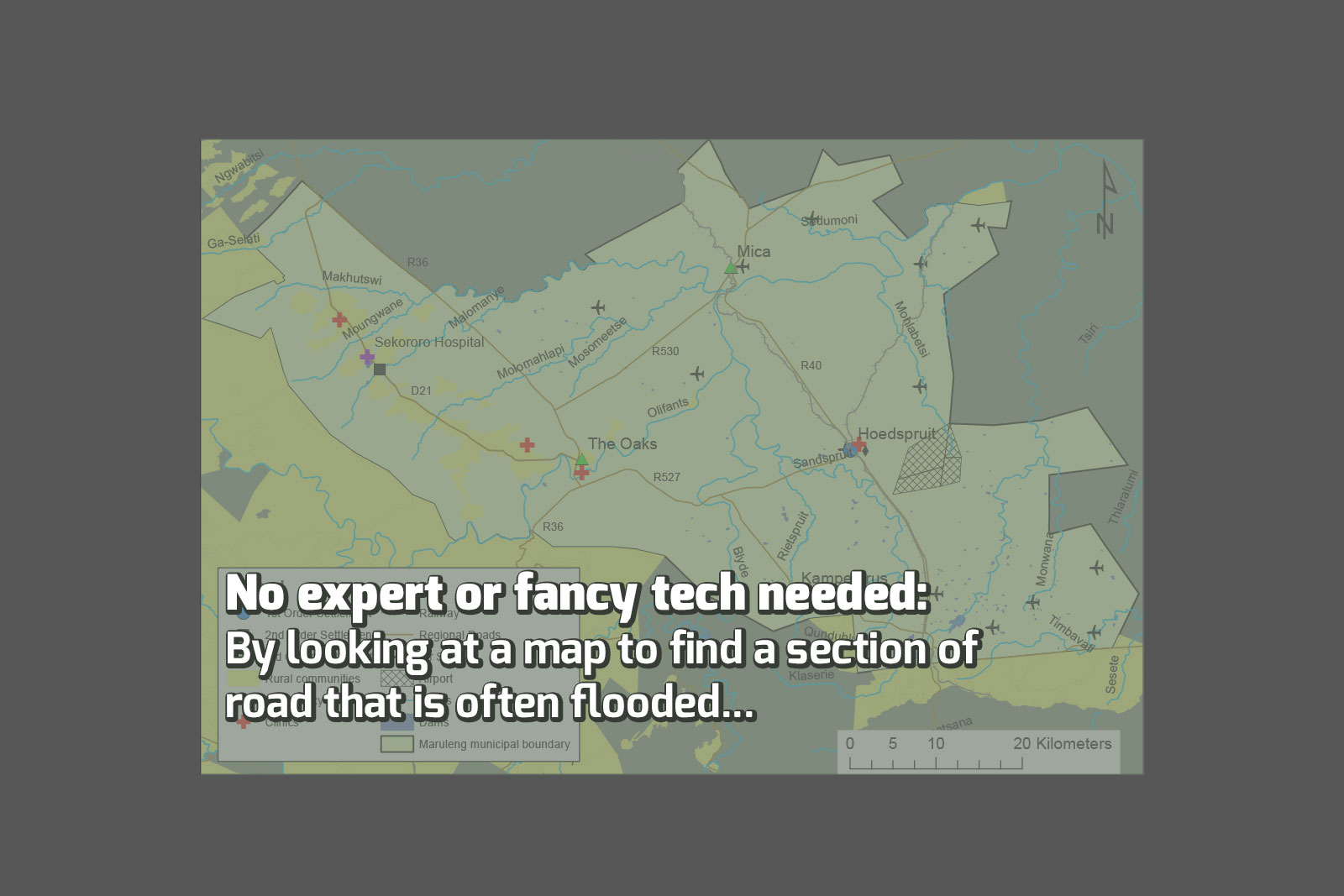

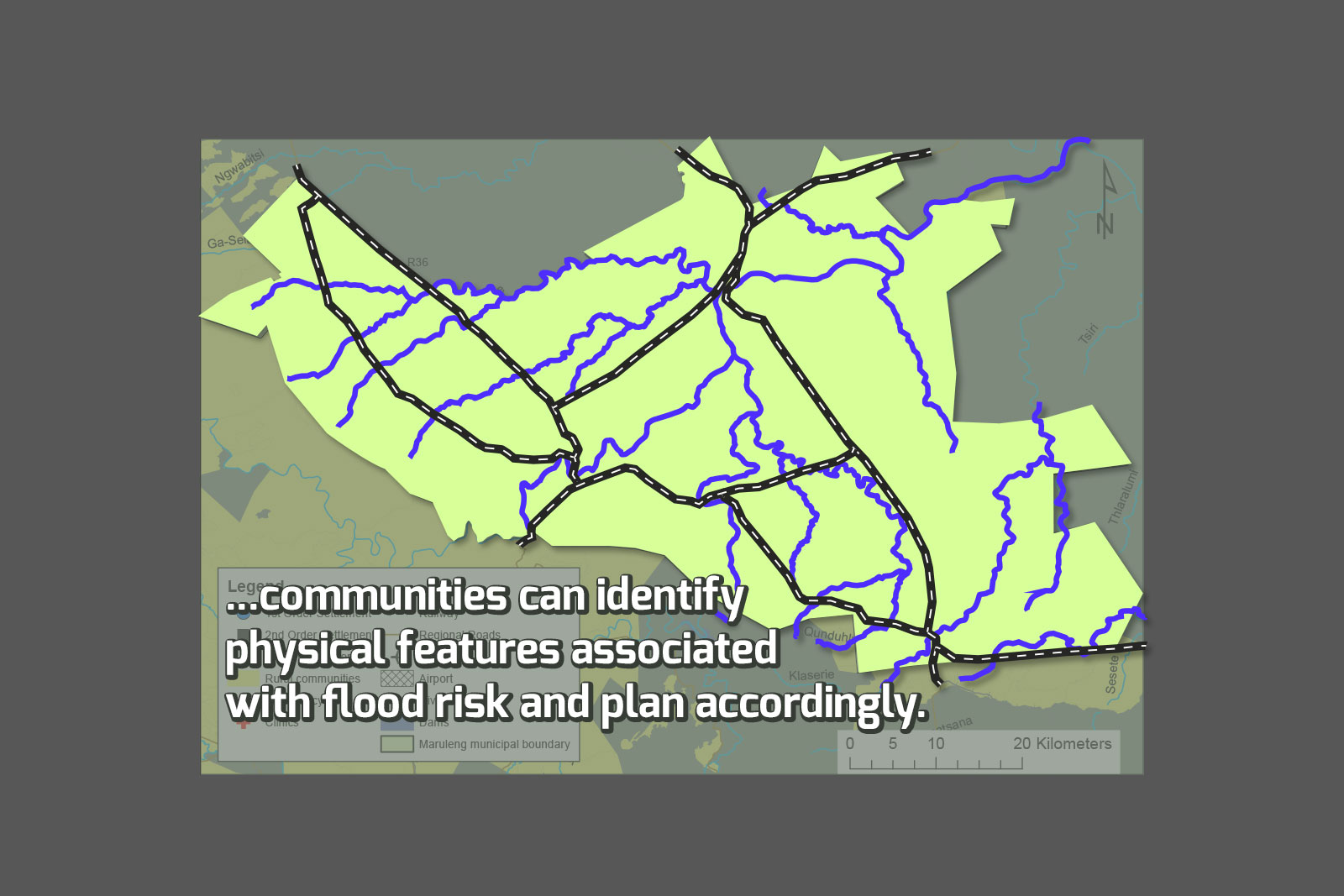

In another example, the group looked at a map in order to identify physical features associated with flood risk, like a certain section of road or a bridge that is often flooded.

Says Kong, “People often think experts and fancy technology is needed, but many times simply thinking the problem through and applying local knowledge can lead to practical recommendations.”

Maruleng settlements and infrastructure. By looking at a map to find a section of road that is often flooded communities can identify physical features associated with flood risk and plan accordingly.

Maruleng settlements and infrastructure

Local flood risk maps

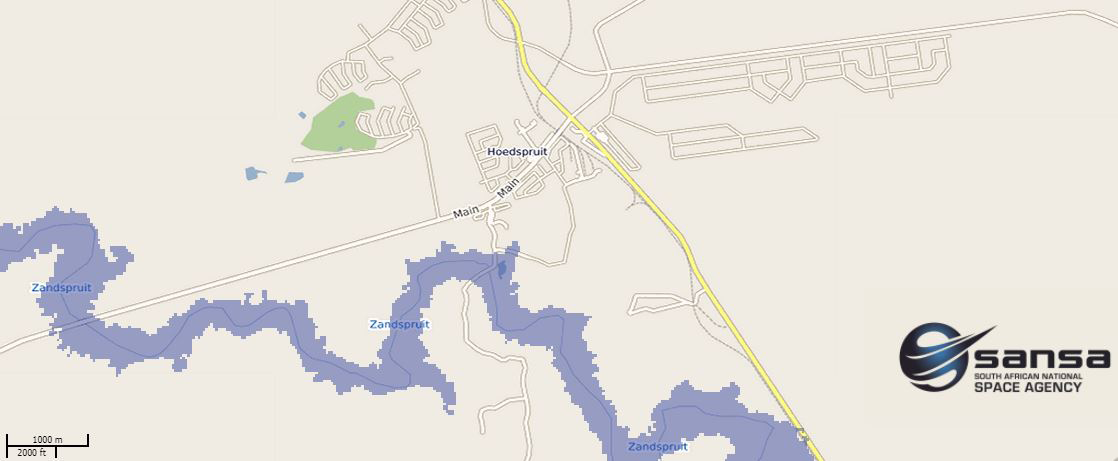

This map shows areas at risk of flooding in Maruleng should river levels rise by five meters. The South African National Space Agency (SANSA) created an online, interactive tool that helps municipalities assess flood risk using maps like these. According to the tool’s developer and remote sensing researcher at SANSA, Phila Sibandze, the map shows which parts of a town could be affected by floods if river levels were to rise by one, three or five meters, depending on the rainfall. As such, the SANSA flood risk map can be used as another indicator to help authorities manage flooding disasters.

Wastewater spillage, an environmental and health hazard, is a major a flood risk

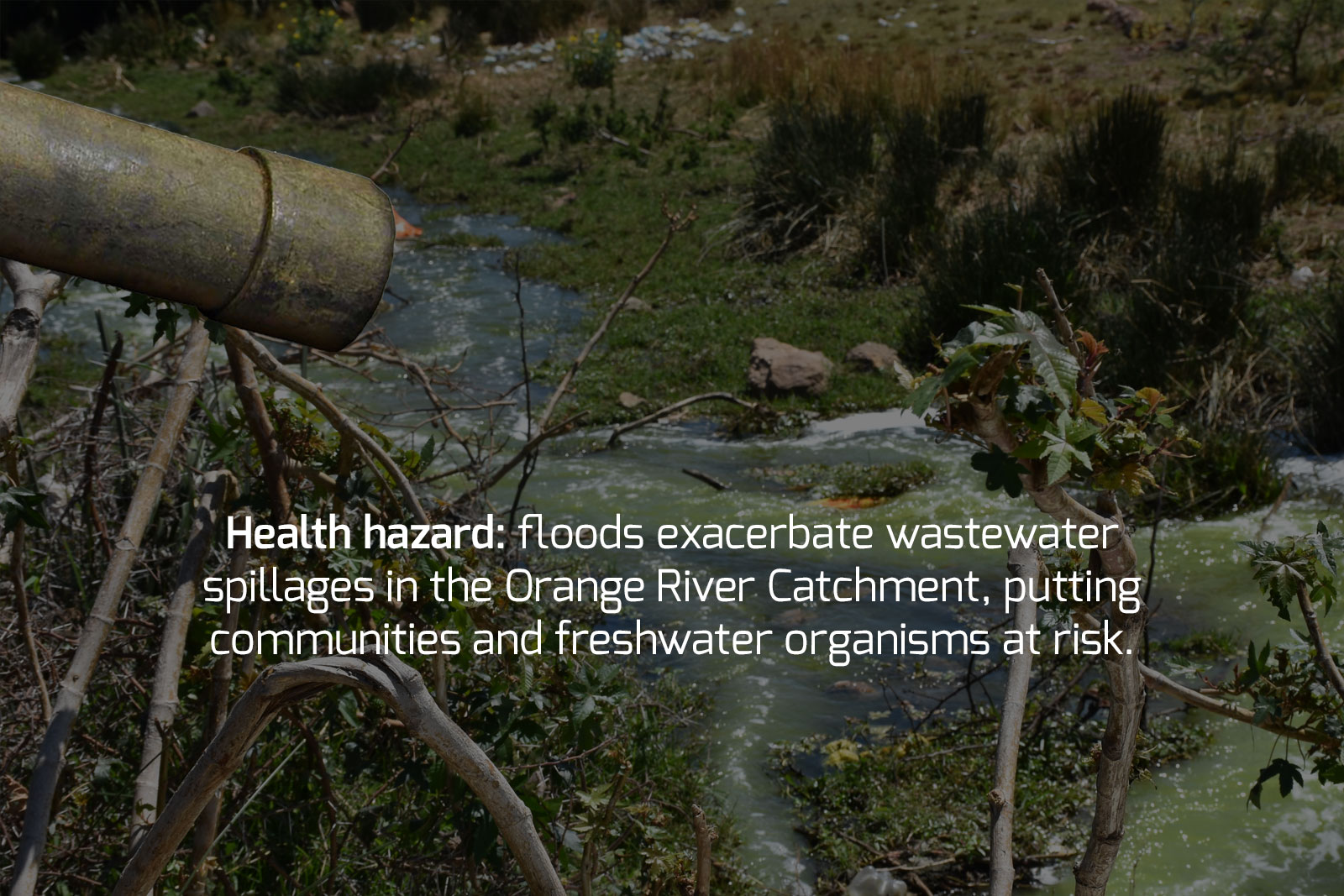

Besides the displacement, injuries and physical damage caused by heavy rains in the Olifants River Catchment, wastewater spillage is a huge risk that requires better flood management and planning.

According to AWARD biomonitoring technician Thabo Mohlala, floods can lead to wastewater spillages that are non-compliant with Green Drop standards.

“Climate change will likely affect this process, with changes in rainfall patterns or flash floods of an erosive character becoming more prominent in most parts of the Lowveld,” says Mohlala.

Wastewater spillages during floods lead to higher water levels that contain more heavy metals (from acid mine drainage) and pollutants, leading to heavy metal accumulation in freshwater organisms, as well as contaminants that affect the health of communities who extract water directly from the river without proper filtration systems.

The main problem is that wastewater systems have not been upgraded to accommodate the population growth in the area, he says. “Most of these systems are choking from high intakes, almost turning them into a bypass for sewerage as it never gets treated sufficiently.”

Wastewater treatment plant in Phalaborwa at Makhushane village discharging wastewater into the village streets.

Wastewater treatment plant in Phalaborwa at Makhushane village discharging wastewater into the village streets.

“These issues require a collaborative approach between the national departments of water affairs and of mineral resources, water resource managers, business and communities,” says Mohlala. “However, the government must play the leading role in directing efforts and evaluating success or failure.”

Zwakele Maseko, senior manager for disaster management in Ehlanzeni, says there are disaster management plans for local municipalities and districts, but that the department of agriculture, for instance, also has its own plan.

“We are working in silos,” he says. “The challenge we have is integrating these plans and checking that other departments’ plans comply with the Disaster Management Act.”

Before meeting with Kong at a disaster management indaba, Maseko’s district was of the view that an external consultant should be appointed to help develop and coordinate disaster management plans. Instead, with the help of Kong’s matchmaking, he says it has emerged that the national department of environmental affairs has experts who can assist free of charge, saving the municipality a substantial cost.

Maseko says Kong is also helping to set up contacts with researchers nationally, as well as disaster managers in Limpopo province so that common inter-provincial issues can be addressed together.

Says Kong, “In Limpopo they may struggle with flood risk management, but in the Western Cape they are doing well, so we can bring experts from Stellenbosch University doing research on this.”

Kong is now establishing what she calls a disaster management “learning network”, which includes university-based groups like the Research Alliance for Disaster Risk Reduction (RADAR), the African Centre for Disaster Studies (ACDS), the Disaster Management Training and Education Centre for Africa (DITEC), the Institute of Semi-arid Environment and Disaster Management, disaster managers, other government representatives and community members, to encourage peer-to-peer learning using social learning approach.

LISTEN: “Can we bring social learning to the rest of the Olifants River Catchment?” – Dr Taryn Kong

While Kong hopes her social learning approach will become a tool sustainably applied in the municipalities of the Olifants River Catchment, Maseko’s take is that better communication and cooperation is needed between neighbouring provinces and with Mozambique.

Referring to the recent floods in the Western Cape, Maseko says other provinces should have proactively offered disaster relief resources when storm warnings were first issued, rather than responding to calls for assistance after the fact.

He hopes the learning network will begin to change attitudes towards mutual learning and multi-disciplinary, inter-provincial collaborations, especially in light of disaster risks caused by climate change.

An Oxpeckers & ScienceLink investigation for #ClimaTracker

Text: Anina Mumm

Graphics/Data Visualizations: Anina Mumm & Artman Designs

Original Photos/Maps: Provided by AWARD

Produced in partnership with Code for Africa and the International Center for Journalists

Funded by impactAFRICA and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.