02 Aug Inside the temple of trade

Thousands of euros change hands at reptile trade fairs, but it’s hard to tell if the deals are legal or not. Rudi Bressa investigates

In the bag: Traders communicate beforehand via social networks and close the deal as fast as they can. Photo: Rudi Bressa

It’s a very busy day at Terraristika, one of the largest reptile fairs in Europe, held in Hamm, Germany. Throngs of people come and go with large polystyrene boxes. Inside there may be a royal python, or a Hermann’s tortoise.

The thing that jumps to mind is the clear difference between the professional breeders and traders, and the occasional customers who come here to buy the next pet. The former look at the event as a business opportunity, while the latter can be seen leaving the fair with a newly purchased box, happy with their deal and new reptile.

Thousands of euros are changing hands. The price for a boa snake ranges from €1,700 to €2,000. Monitor lizards, Uromastyx lizards and chameleons range from €75 to €300, and royal pythons from €200 to more than €1,500.

Outside in the fair’s parking lot are vans and cars that come from all over Europe. Some are refrigerated to keep the temperature inside just right for the reptiles being transported.

In the exhibition halls, many of the species on display are protected by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), which regulates the international trade in protected and endangered species. Some boxes offer for sale an Argentine boa, a Burmese python and Egyptian turtles – all species listed on CITES Appendix I that should not be allowed to be sold, except for scientific purposes.

Many other species are covered by Appendix II, which only allows strictly controlled trade. Examples include a Blood python, African savanna monitor, Panther chameleon and many geochelons originating in China and Vietnam.

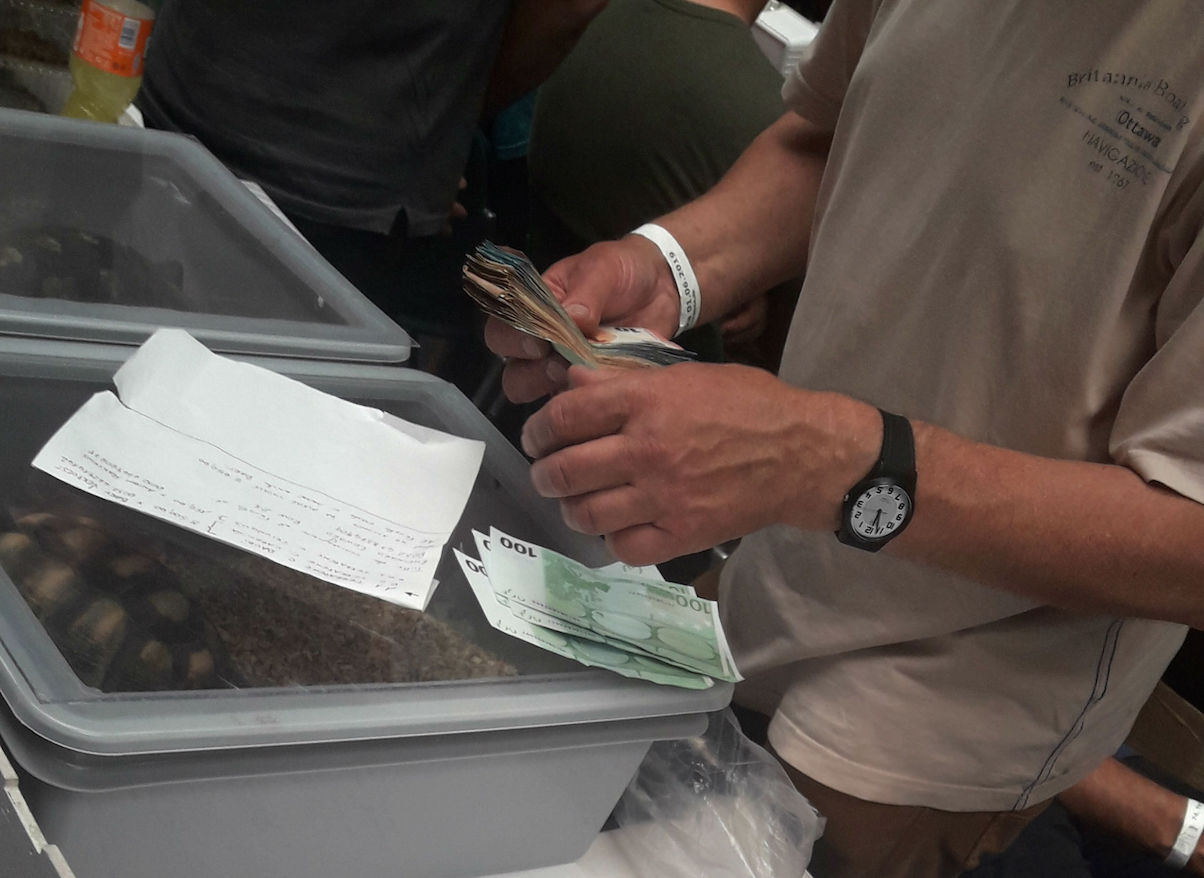

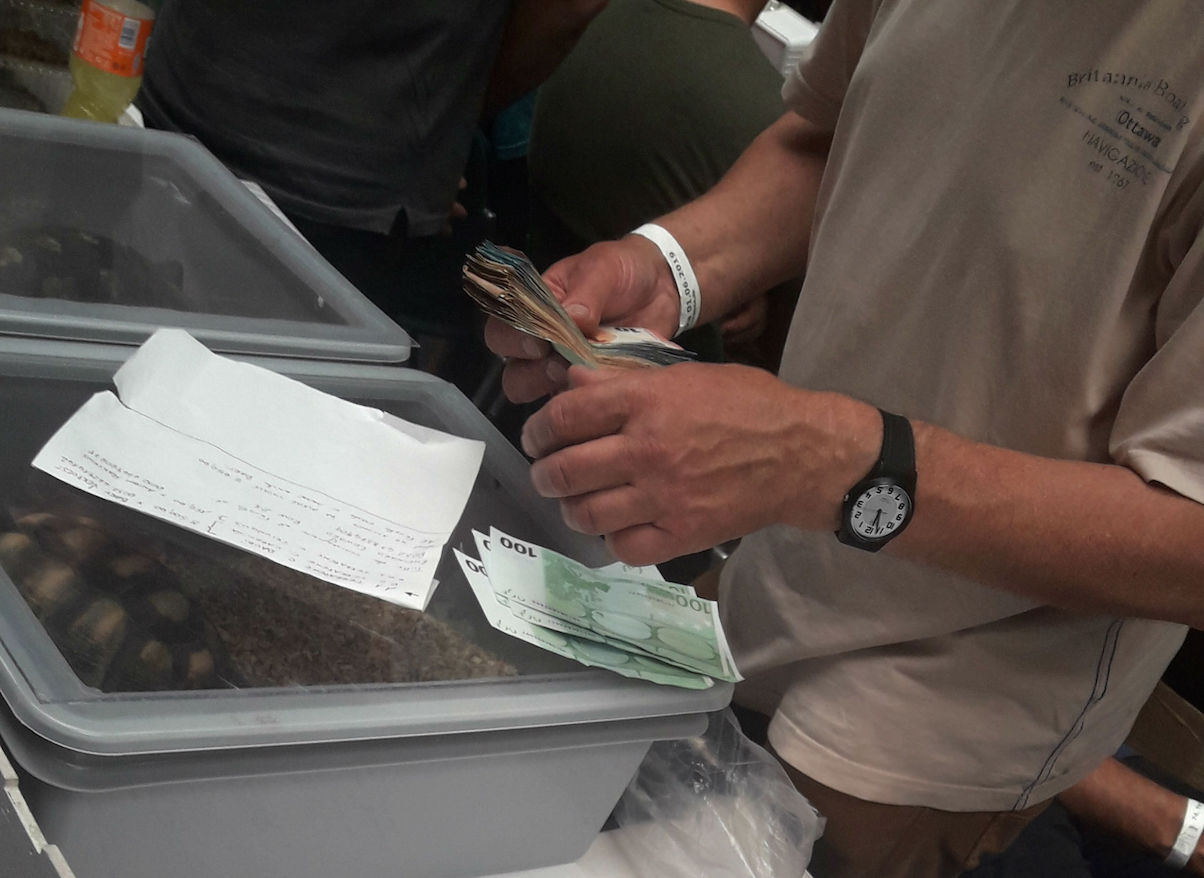

Traders here know each other and they communicate via social networks: “Hey, do you remember me? We met on Facebook.” Some have ongoing chats on Whatsapp, which helps them to close a deal as fast as they can: a quick look at a python inside a cotton bag, a signature on the document that should certify the lawful origin and, finally, the payment. The deal is done.

Every seller has a website to show off the merchandise. Some of them have done a good job, like Timo, whose boxes are empty before noon. “Today I had a good day,” he says. Asked where his reptiles came from, he says: “They come all from South America.”

Money maker: Professional traders and breeders treat the event as a business opportunity. Photo: Rudi Bressa

Legal or not?

It’s hard to tell what is legal and what is not. Asked about whether his merchandise is legal, Timo becomes suspicious and closes off the conversation: “Sure, it’s all legal.”

All the documents at the fair are paper and it is unclear whether there is a master set where they are all collated, and if they should be made available for checks by wildlife experts. At the information desk an official says it’s necessary to register each outgoing animal before leaving the fair.

“Everything that goes in and out must be recorded here,” says one of the sellers, an active trader who continuously goes in and out of the fair. “Someone can buy a reptile and then resell it shortly thereafter, perhaps at a higher price.” Perhaps also with a date of birth different from the original, which makes it difficult to trace the origin of the animal, whether it is from breeding stock and grown in captivity, or caught in the wild.

“Here 60% of the animals you see are all WC [wild captured] and recently imported,” says the seller, although in most cases the abbreviation used to describe the reptiles is CB (captive breeding).

By 1pm the fair is emptying and the traders with reptiles left over put them back in their carriers. The best deals have been done, and it’s time to prepare for the next reptile trade fair.

This investigation is part of a transnational series investigating how online illegal wildlife trade facilitates illicit financial flow, produced with the support of the Money Trail project.

Rudi Bressa is an Italian freelance journalist and contributing author who writes about nature, conservation, climate change, energy transition and sustainable development. He has published several stories about poaching in Italy and contributes to LaStampa, LifeGate, Renewable Matter and other media.