06 May Africa’s pangolins caught in ‘the perfect storm’

Recent seizures of huge hauls of scales have turned Nigeria into Africa’s key illegal pangolin exporting country. Alexis Kriel investigates what is driving the trade

Lagos market: The peddlar offered two live pangolins to a Chinese undercover volunteer called ‘African Warrior’. Photo courtesy China Biodiversity Conservation and Green Development Foundation

“African Warrior” is a Chinese conservation activist who volunteered to travel to Nigeria in West Africa earlier this year to investigate the illegal trade in pangolins. For the sake of her security, and to protect her anonymity, her group gave her the soubriquet of a leader setting out to war.

She provided regular updates on her progress in Nigeria to the China Biodiversity Conservation and Green Development Foundation, the environmental NGO that sent her there. Corresponding with them on WeChat, the Chinese social media app, she described what she found in a Lagos market:

“The local peddler has two living pangolins. He can speak Chinese. The pangolins have been kept in a bag wrapped in two layers; the outer layer is a flour bag with the Chinese name of the flour printed on it, and the inside one is a yellow bag with English letters.

“The peddler kicks the pangolins with his foot, indicating that they are alive. Another ragged peddler takes a pangolin out of another bag – it is curled into a ball. He lifts it up and throws it on the ground. After the pangolin uncurls and starts to move away, the peddler steps on its tail.”

The foundation is achieving what few organisations, in China, have achieved before in the efforts to save pangolins from extinction. In September 2018 the foundation filed the first domestic public-interest litigation against the state forestry department of Guangxi Zhuang for negligence after 32 rare and endangered pangolins that had been confiscated died while in the state department’s care. In January this year, the foundation obtained notice of acceptance of the lawsuit and the first public-interest litigation case involving pangolins in China was officially approved and is currently being heard.

Since then, the Chinese government has agreed to co-operate with the foundation to create new pangolin legislation, which it hopes will lead to the elevation of pangolins from a Grade II to a Grade I animal in China. This will mean permits for hunting pangolins and the use of pangolin scales are decided on a state level, as opposed to a provincial level, affording greater protection to pangolins and regulations more in line with those contained in the Convention in International Trade in Endangered Species (Cites).

Dr Jinfeng Zhou is the Green Development Foundation’s secretary general and the first chairperson of the China Pangolin Research Centre, a private organisation established in February this year in a signed agreement with Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University.

“We must fight for change urgently. We need more stakeholders,” said Zhou.

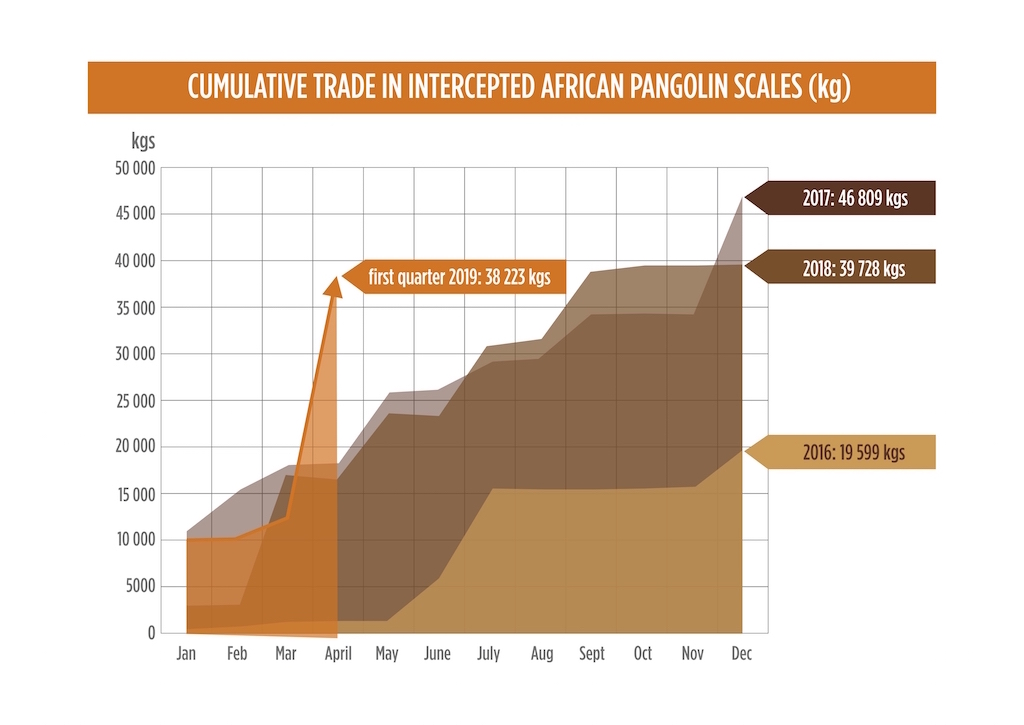

Drastic surge: The growing demand for pangolin scales has contributed to making it the most heavily poached and trafficked mammal on the planet, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature. Graphic: Lori Bentley

Boasting rights

In Hong Kong business people are treated to pangolin meat openly, despite laws that prevent its consumption, and it is often used for boasting rights during business deals. The scales are used in Vietnam and China for traditional medicinal cures.

The recent drastic surge in the illegal trade of pangolin scales has created panic among conservationists and environmental NGOs, who see the spike as signalling an acceleration on the course to extinction for this endangered animal that is high on the red list of threatened species of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

A confiscation of pangolin scales from Nigeria destined for China, amounting to 9.14 tons and intercepted by Hong Kong customs in February 2019, was the single largest confiscation of pangolin scales in history.

Then, in April, there were two confiscations of scales in Singapore, a week apart. The scales were sent from Nigeria and were bound for Vietnam. The two amounts were just under 13 tons each and, combined, represented the deaths of an estimated 40,000 pangolins.

As a result of the large quantities of scales being confiscated, Jinfeng Zhou’s foundation set up a team to investigate the illegal use of pangolins in Nigeria. His team’s work is devoted to opening up avenues for co-operation with Nigeria to stem the trade and to enforce the law.

He has sent letters to the Nigerian Embassy in Beijing, the minister of environmental protection for Central Africa and to the Nigerian president, hoping to strengthen ties between the two countries for protecting pangolins and other endangered wildlife species. As a result of these letters, the foundation has been invited to participate in the National Biodiversity Conference to be held in Nigeria from May 20 to 22, under the theme “Delivering Nigeria’s business deal for nature”.

“We hope that Chinese corporations in Nigeria will bear social responsibility. They should donate to endangered wildlife, like pangolins – it is conducive for enhancing their public image to the world, and encourage their employees to participate in conservation,” Zhou said. He believes every Chinese citizen applying for a visa to visit Nigeria should be routinely informed that trade in pangolins is illegal.

“The Nigerian government must establish strict and clear laws to improve the punishment system, and at the same time increase publicity. Relevant knowledge should be popularised from rural to urban areas, with increased public participation,” he said.

Nigeria has ratified the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species, which has banned all trade in Pholidota – the definitive order of pangolins, comprising all eight species. It remains the key exporting country of pangolins to Asia, however – according to the Nigeria Customs Service, in 2018 alone the illegal trade in pangolin scales seized in the country had a value of US$900-million.

Lagos is Nigeria’s largest city and has become the collecting hub for pangolin scales from Nigeria and neighbouring countries Cameroon, the Central African Republic, the Republic of Congo and Gabon, according to a recent threat assessment prepared by the United Nations office on drugs and crime (UNODC).

The Nigerian law that governs protection of pangolins falls under the Endangered Species Act, which states: “No capture, local or international trade is allowed. For a first offence, a fine of US$1,500 may be imposed and/or imprisonment up to five years.”

Cites has no record of arrests or convictions under this legislation in Nigeria up to September 2017, and is currently seeking updated information in preparation for the upcoming Cites COP18 meeting.

Oxpeckers sent questions relating to the confiscations of pangolin scales originating from Nigeria this year, as well as whether there had been any arrests and prosecutions in connection with the illegal trade in pangolins, to Sikiru Tiamiyu, Nigeria’s spokesperson for the Convention on Biological Diversity, of which Nigeria is a signatory. Tiamiyu said he had passed them on to the Nigerian environment minister and the director of forestry, but their responses had not been received at the time of publication.

The former minister of environment, Ibrahim Usman Jibril, said in response to the seizure in August last year of 7,100kg of pangolin scales alleged to have originated in Nigeria by Japanese customs officials that investigations had been initiated.

The Nigerian Federal Ministry of Information and Culture quoted Jibril as saying the source of the scales could not have been Nigeria because pangolins were near extinction in the country and Nigeria was being used as a transit route for illegal wildlife trade.

“… there has not been any case of illegal wildlife trade from Nigeria as a source country. However, globalisation allows and encourages international trade which traffickers have exploited and exposed us to some of these unwholesome practices which we frown at as a nation and defender of endangered species,” he said.

Jibril resigned as environment minister in December 2018 and was not prepared to comment on the recent confiscations of scales linked to Nigeria, passing on questions to the new minister, Suleiman Hassan Zarma.

A white-bellied pangolin for sale in a ‘chopbar’ in West Africa. Photo: Rob Bruyns

Perfect storm

It is the perfect storm that brings together these two disparate countries in an exchange that suits both parties but is driving Africa’s pangolins to extinction.

In most African supply countries, pangolins are traded as bushmeat in local markets which double up as a source of scales for export to China and Vietnam. Bushmeat is used as a source of protein and of income during lean agricultural periods in many West and Central African countries.

More than half the population in Nigeria lives below the poverty line; pangolins are still available in bushmeat markets, every day – although, according to local accounts, because of alarming rates of harvesting, they are becoming harder to find.

“The market tradesman calls me often and asks me if I want pangolins,” said African Warrior. “They can get pangolins and they are looking for a market. Chinese people are eating pangolin soup in Lagos, every day.”

The African headquarters of many international Chinese companies are based in Nigeria, employing thousands of Chinese citizens who earn at least 10,000 yuan (about $1,500) a month. The American Enterprise Institute estimated the value of Chinese investments and construction contracts in Nigeria at US$21-billion between 2016 and 2018.

According to African Warrior’s research, most of the pangolins traded in Nigeria are sold to members of the Chinese community, as individual animals (for domestic use) or in bags of scales (for export).

The local traders told her they could provide from 200kg up to 500kg of scales a month. The scales are stockpiled and shipped to Asia hidden in containers and enclosed in packages labelled and marked as an inconspicuous product – such as “frozen beef” or “sliced plastics”.

Field studies in Central and West Africa conducted by UNODC showed that hunters who had previously sourced pangolins for their meat are now capitalising on the scales, and that the supply is being “crowdsourced” to include part-timer and non-specialist hunters. The meat markets serve as a central point for the aggregation of scales.

The hunters interviewed in the UNODC study knew that hunting pangolins without a licence was illegal, but most said the offence was less serious than other forms of poaching – for example, the poaching of elephants. Fear of enforcement did not play a big role in their decision making.

African Warrior said when she was in Nigeria police were present and police cars were parked at the entrance to the market in Lagos, but they turned a blind eye to the flagrant trade in wildlife.

“By the time I arrived at the market, it was afternoon. Pangolins were sold out, leaving only crocodiles, lizards, snakes and turtles – all captured from the wild. Even before entering the market, I was surrounded by peddlers who recognised me as Chinese and wanted to sell me wild animals,” she said.

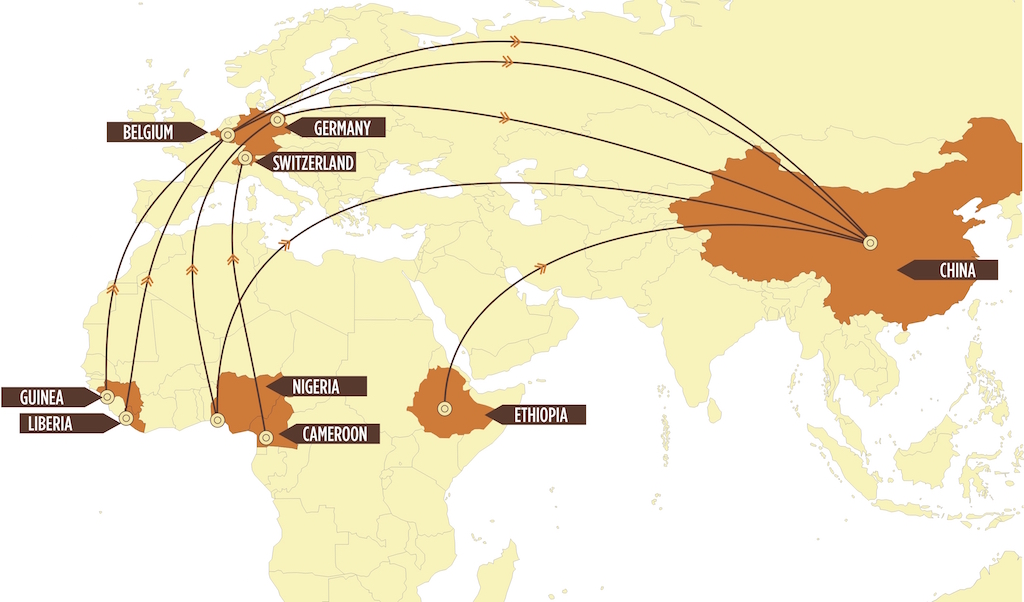

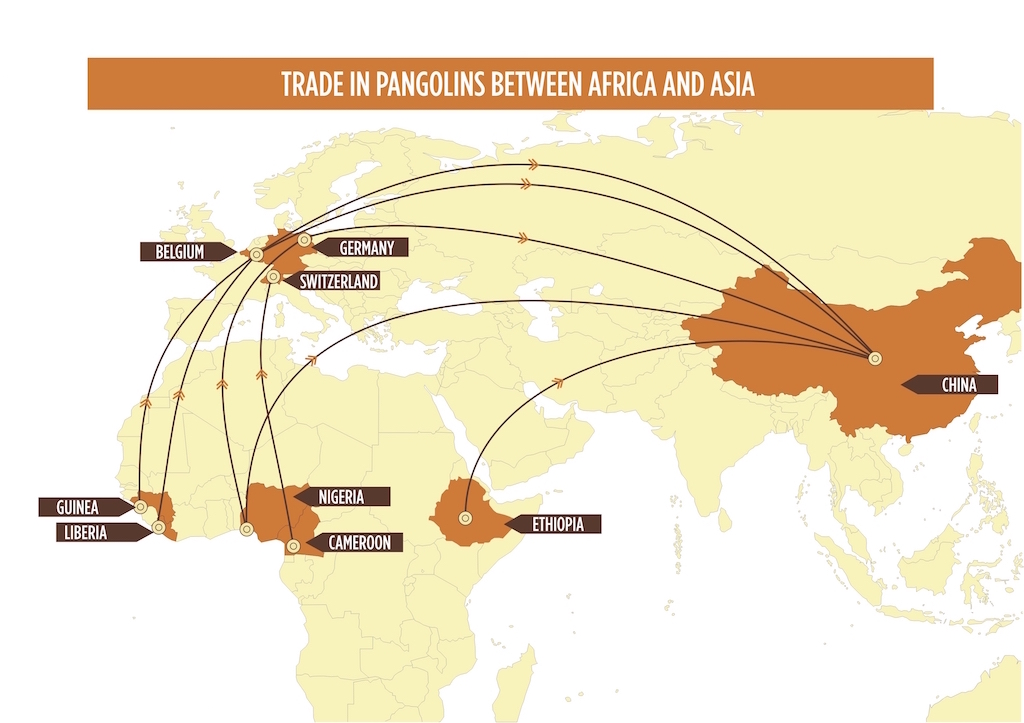

Global trade: Traffic found that most of the air shipments of pangolin products out of Africa routed through European countries. Graphic: Lori Bentley

Trade routes

Research by Traffic, the global wildlife trade monitoring group, found that most of the air shipments of pangolin products out of Africa routed through European countries and that trafficking trade networks were constantly shifting.

Traffic analysed 1,270 seizure incidents between 2010 and 2015 and found that the trade involved 67 countries and territories across six continents. The report demonstrated the global nature of pangolin trafficking, which is not limited to Asian and African range countries – though trade outside of Asia and Africa is poorly understood.

The African Pangolin Working Group, a non-profit organisation set up in 2011 to conserve Africa’s pangolins, sent a team to investigate the bushmeat trade in pangolins in Ghana, West Africa, between September 2013 and January 2014. (The author of this article is the projects director of that group.)

The team found that at the rural eating houses where bushmeat is served, referred to colloquially as “chopbars”, pangolin scales used to be a by-product of the pangolins sold as bushmeat and were discarded. In recent years the scales have become a valuable commodity that is sought as the primary product, and the meat has become a derivative.

More recent research by the working group in Southern Africa found in-country and cross-border trade in pangolins in and between South Africa, Zimbabwe, Mozambique and Botswana. In South Africa the trade is mostly in live pangolins, with limited scales being sold through muthi (medicine) markets for use in traditional African cures.

Colonel Johan Jooste, national commander of South Africa’s Directorate for Priority Crime Investigation in the South African Police Services, responsible for combating and preventing national priority crimes – including trade in threatened and protected species such as pangolins – said recent court cases that had resulted in convictions and sentencing of pangolin traders served as a deterrent.

“There is currently no indication of syndicates involved in the trafficking of pangolins in South Africa. All arrests show that what we are seeing is opportunistic individuals who want to make money but do not have a market to sell these animals. They are fishing for potential markets when they get arrested,” Jooste said.

Chopbar: At rural eating houses where bushmeat is served, pangolin scales have become a valuable commodity. Photo: Rob Bruyns

Criminal syndicates

Ofir Drori is the founder of Eagle, a group that has been instrumental in the arrest, prosecution and convictions of wildlife poaching and trafficking syndicates in nine African countries. He described a syndicate-driven racket behind the pangolin trade – with traffickers who have one foot in Asia and one foot in Africa propagating the supply and demand in both countries.

They are Chinese but are integrated with high-ranking government officials from Africa – corrupt ministers, ex-ministers and mayors, who are investing back into the syndicates for further buy-in from customs people and police commissioners, he said.

Drori said these networks existed in Africa from as early as the 1980s, operating in many countries simultaneously. “When there are high margins, the syndicates intimidate the freelancers and form monopolies – those who were doing rhino horn and ivory added pangolins.”

He is critical of big conservation NGOs which he believes have been aware of the syndicates trafficking wildlife for two decades but have failed to find a solution. “The only way we will be successful is if we have a very serious shift regarding conservation. There is a huge conservation machine, [but it is] not making progress,” he said.

Pangolins, now commonly referred to as the most traded mammal on earth, were previously conspicuous by their absence in conservation awareness. They have garnered attention worldwide since being uplisted from Appendix II to Appendix I by CITES at COP17 in South Africa in 2016. This legislation intended to regulate international trade, but more than two years later the international trade has increased.

Drori said the Eagle template is to be active on the ground, infiltrating criminal networks, setting up sting operations, co-operating with law enforcement agencies to enact arrests, preventing corruption and creating deterrents through awareness.

According to Drori, the criminal syndicates involved in the illegal pangolin trade have boosted the rate of distribution and increased marketing. “It is a positive-feedback-loop – pangolin scales became extremely profitable and they are establishing a cycle of ever-increasing supply and demand,” he said.

Alexis Kriel is a freelance journalist and projects director of the African Pangolin Working Group. Reporting for this story was supported by a special grant from Internews’ Earth Journalism Network’s Asia-Pacific Project.