31 Aug The black market for jaguar body parts

Across Asia and the Chinatowns of Europe a growing demand for jaguar body parts is placing pressure on the big cats of the Americas. Eduardo Franco Berton investigates

One of Brazil’s most alarming cases was the confiscation of 19 dismembered jaguars found in a freezer in Curionópolis, Pará in 2016. Photo: Déo Martins/Infopebas

At first glance Li Ming and his wife, Yin Lan, look like an ordinary Chinese couple. While they are sitting on a bench, they receive with broad smiles and kindness the relatives who come to visit them. It is lunch time. One of the visitors approaches the couple with two bags of rice and chicken.

Yin stands up and politely asks the policewoman who is sitting next to me to unfasten the shackles that are cutting off her blood circulation from her hands. Almost three hours have passed now, and the judge who must attend the case of illegal wildlife trafficking for which Ming and Lan are being accused does not show up. The hearing is suspended for the sixth time.

Li Ming and Yin Lan are Chinese citizens with Bolivian identity cards. On February 23 2018 they were apprehended in their chicken restaurant in the city of Santa Cruz de la Sierra, in possession of 185 jaguar fangs, three skins of this feline, several parts from other animal species, one 22-calibre pistol and a large sum of national and foreign money.

After a two-month follow-up, authorities from the Santa Cruz government, national police and the public prosecutor’s office carried out a joint operation that ended with the apprehension of the Chinese couple. It’s an unprecedented case, and one that the authorities consider to be a major blow for Bolivian biodiversity.

Between 2013 and 2018, around 171 jaguars were stalked and massacred in Bolivian forests, one of the worst killing rates since the 1970s, when these big cats were chased for their skin. Nowadays they are victims of the black market of jaguar parts, mainly fangs.

By August 2018 authorities had seized a total of 684 jaguar fangs from Chinese smugglers. Of these, 119 fangs extracted from Bolivia were confiscated by customs authorities in Beijing, China. In most cases, the fangs were camouflaged in the middle of key rings, necklaces, chocolates and wine boxes, to hide the crime.

These illegal goods form a monument to human greed, promoted by superstition and the dark business of wildlife trafficking, which each year moves an estimated $19-billion worldwide, and which today is among the threats to the biggest cat in the Americas.

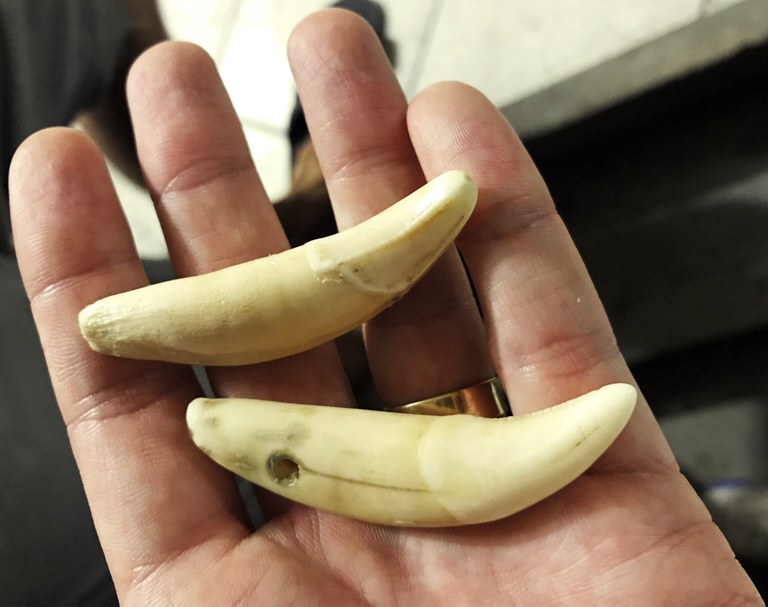

Fang traffickers offer between $100 and $150 for each jaguar fang. This price rises as high as $5,000 in China. Photo: Eduardo Franco Berton

Jaguar fangs

For more than 1,000 years the use of Asian tiger parts has been part of the traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) regime, as an alternative to expensive Western medicines. Although China banned the use of tiger bones in 1993, the sale of the product and its derivatives never stopped.

Western medical experts tend to ignore the healing power of the tiger parts, which they attribute to similar properties as those of an aspirin, but in China, Taiwan, South Korea, Vietnam and the Chinatowns in Europe and North America, the drug stores sell products derived from tigers. Trade has increased since the 1980s as the growing Chinese middle class gained more purchasing power and the use of TCM gained more prestige.

Considering the scarcity of Asian tigers, with a population estimated at just 3,200, the Asian demand seems to have found the perfect substitute: the jaguar. This is putting pressure on the 173,000 jaguars that are estimated to inhabit the Americas, according to a recent study.

Richard Thomas, from the global wildlife trade monitoring organisation Traffic, says jaguar’s fangs and claws are entering the illegal trade as substitutes for Asian tiger parts.

It was in this way that the authorities apprehended Li, a Chinese businessman who used to live in Bolivia. He was caught at Beijing airport on March 18 2015 with 119 jaguar fangs which he had hidden under carefully packed wine boxes. Li is now serving a sentence of four and a half years in prison for the crime of smuggling wildlife. In addition, he had to pay a fine of $7,826.

According to data from the National Migration Office, 28,800 Chinese citizens arrived in Bolivia in the period 2015-2017. Of these almost 70%, or 20,098 people, entered for tourism, 1,203 entered for work, 3,687 for unspecified reasons and 3,490 were returning to the country.

Liang Yu, the ambassador of China in Bolivia, told the press that his country’s cooperation in Bolivia was worth more than seven billion dollars by 2018. This money is being invested mainly in the construction of roads, industrial plants of sugar, potassium and lithium. The diplomat said Bolivia is the most important trade partner that China has in the Latin-American region.

But Chinese loans are not free of conditions. The Bolivian Supreme Decree No 2574 of November 3 2015 states that contracted companies must be “conformed to the majority of capital from natural or legal persons from the China Republic, who are incorporated in their country of origin or in the territory of the Bolivia”.

In an interview with the press, Angela Nuñez, a biologist who specialises in wildlife management and conservation, said the growing trade links between Bolivia and China have allowed a large number of Chinese citizens to enter the country. And a large number of these citizens are encouraging illegal hunting and creating illegal trafficking networks.

Marco Antonio Greminger shows 25 jaguar skulls that were confiscated in a jewellery store in the municipality of Santa Ana, Beni, in 2016. Photo: Eduardo Franco Berton

Black market

At a local market in the city of Trinidad, capital of the Department of Beni, Bolivia, I enter what looks like a common craft shop. On the shelves are two jaguar skulls that seem to belong to juvenile felines because of their size. The skulls still have all their fangs.

“Do you have bigger fangs?” I ask the seller, who waits for a client to leave before answering me.

“Yes. Come here,” he whispers.

From a drawer he pulls out three large jaguar fangs, about eight centimetres each, which he places on a table with a transparent plastic tablecloth.

“How much are these?” I ask him.

“They cost 100 dollars each. If you notice, they are bigger than those in the skulls.”

“I am interested. Could you sell me 10 fangs on collars?”

“Sure. I can prepare them by tomorrow afternoon.”

“Okay. Can I take a picture of these three fangs?”

“Do not! Then the police could come.”

“It must be a delicate issue, right?”

“No… they will sentence me to three years and I will get substitute measures and will not go to jail, but they will still make me waste my time. And I will shoot the ‘asshole’ that does that to me, and then I will be imprisoned 30 years for murder.”

During my visit I observed the illegal sale of four skulls and 26 jaguar fangs. The fangs I was offered at $100 dollars can cost up to $1,500 or $5,000 in China – rivalling the cost of rhino horns on the black market.

According to Marco Antonio Greminger, who is in charge of the wild fauna conservation project in the departmental government of Beni, Bolivian environmental law provides a lenient penalty of up to six years in jail.

“If they find someone selling jaguar fangs and this person admits his guilt, he will undergo an abbreviated trial in which he will get a three-year sentence and will not go to jail. The only thing he is obligated to do is sign a daily book, and after all he will continue with his illegal business, which generates a lot of money,” said Greminger.

Jaguars are listed as vulnerable by the Red Book of the Vertebrate Wildlife of Bolivia. According to a recent study published in PLoS One, a scientific journal, the estimated population of jaguars in the country is 12,845.

A decorated jaguar skull offered in one of Iquitos’ handicraft shops. Photo: Eduardo Franco Berton

Craft shop sales

I head to the corridors of the lower part of the Belen market, in the Amazonian city of Iquitos, Peru. In one of the stalls, a stuffed boa constrictor catches my attention.

“Come young man, if you want I can wrap it up so you can pass it through the airport,” the saleswoman tells me.

“I have been told that you have jaguar fangs,” I tell her.

“I had but I have sold them all. But when the river waters go down they will bring me some more. Would you be interested in buying skins?”

“Perhaps.”

The woman takes me to a warehouse with a large blue wooden door and a silver padlock; inside it she hides two jaguar skins, which she offers me for 200 soles each, or the equivalent to $61.

“How can I pass these skins trough airport controls?” I ask.

“If you want, I can ask a man that can cut the skin into pieces. He will charge you 50 soles, and then you can take it in your suitcase.”

“Thank you. I have to think about it.”

“And where can I get the fangs?”

“You must go to the craft shops.”

At the craft shops I find several shops are offering jaguar fangs, some with a built-in collar. Other shops have them hidden from public view.

“You will not find bigger fangs in Iquitos, because there are a lot of buyers who pays $100,” one seller tells me.

“Who buys them?”

“The Chinese. They are buying them.”

The bigger fangs are being offered at approximately 250 to 300 soles ($76 to $91) and, depending on their size, the smaller ones at 100 or 150 soles ($30 to $45).

In one of the stalls a woman offers me a skull of a juvenile jaguar at 350 soles and tells me that the next she can prepare for me a “beautiful” necklace with the four fangs.

In another store a salesman tells me that due to the high demand for the fangs, there are people who are wearing down the teeth of sea lions to make them look like jaguar fangs.

“The Chinese look for the Otorongo [jaguar] fangs as if it were gold,” says the man, while he shows me a jaguar skull that he has hidden in a bag.

Dustin Silva, from the wildlife office at the regional environmental authority of the Department of Loreto, said the demand for fangs and other body parts could make the jaguar population of Peru — estimated at 22,210 individuals according to a recent scientific study — go into decline, considering that they only reproduce once a year.

“The jaguar fangs’ trafficking is a very attractive market for trade. While this market exists, the supply and above all the demand for these products will grow,” he said.

Gabriela, who sells jaguar skins and fangs in a community near Iquitos, explains to her buyers that they should hide these products to evade controls from the Peruvian authorities. Photo: Eduardo Franco Berton

Smuggling fangs

Gabriela, a Peruvian who sells jaguar skins and fangs around Iquitos, explained how buyers smuggle fangs: “We grab dried leaves and wrap them very nice. We teach them that they have to hide it in the middle of their clothes, because if customs finds out they will take it away.”

Gabriela had recently sold eight jaguar fangs. “After I sold my fangs people kept asking if I have more and more, almost every week. Just a week ago a Chinese guy came and asked me if I had more fangs to sell.

“The Chinitos [Chinese] love them because when you wash the fangs they are bright white, like little pearls,” she said.

According to a report from the National Forestry and Wildlife Service (SERFOR), during the period 2000-2015, a total seizure of 38 jaguar fangs was recorded in Peru. They were confiscated in warehouses in the city of Lima in March 2015.

Rosa Vento, who is the manager of the Wildlife Traffic and Health Specialist Initiative at WCS Peru, says there were another 34 jaguar seizures during that period. Nine were skulls, 14 were skins and 11 were live animals.

“It is necessary to strengthen efforts to educate and sensitise the population about what illegal trafficking implies,” Vento said.

Miriam Cerdan, director of the general direction of biological diversity at the Ministry of Environment in Peru, said trafficking of jaguar parts was not very intense in Peru. “There is not a seriousness that we can notice in the country at this moment.”

However, during my visit to Iquitos I observed a worrying situation. In just seven days I witnessed the sale of 44 jaguar fangs, four skulls, five skins and about 70 claws. All these products once belonged to about 24 jaguars.

In addition, a large majority of the vendors claimed to have had jaguar products for sale and that soon, when the river levels dropped, the hunters would bring them back more products.

Over the past five years there have been 30 seizures of jaguar body parts in Brazil, which meant the death of at least 50 jaguars. Photo: Déo Martins/Infopebas

Brazil’s skin market

Thais Morcatty is a Brazilian biologist doing her doctorate on wildlife trafficking at Brookes University in Oxford, United Kingdom. As part of her investigations Morcatty found that at least 30 seizures of jaguar parts took away in Brazil during the past five years. This meant the death of more than 50 jaguars.

“That seems little but it is not, because what we have managed to see so far is certainly a very small part of what is really happening, since it is an extremely hidden trade,” said Morcatty.

The main seizures have been skins, which shows that the illegal Brazilian market still demands them. “We have evidence of trade, including international trade within our territory,” she said.

Morcatty stressed that each jaguar is important for forest biodiversity, since they are predators that occupy a large area (between 50 and 300 square kilometres) and are in charge of controlling the population of other mammals. Removing one individual from a population can cause an imbalance in a large area of the ecosystem and an impact on the functionality of the forest.

A jaguar occupies territory covering 50 to 300 square kilometres, fulfilling a vital role in regulating the populations of other species, mainly herbivores. Photo: Eduardo Franco Berton

Disappearing kingdom

In the Americas the historical habitat of the third largest cat in the world has been reduced by 46%.

A 2016 study determined that the jaguar’s distribution in Latin America, for the most part, is affected by the loss of habitat. This is due to the transformation of forests into soybean crops and other forms of large-scale intensive agriculture, and the establishment of pastures for livestock, and smallholdings.

For Peter Olsoy, one of the authors of a scientific study that has quantified the effects of deforestation and fragmentation on jaguar populations, the corridors used by these felines to connect among disparate populations is the most affected. The study quantified the amount and rate of deforestation of jaguar conservation units and the corridors between the year 2000 and 2012. The results indicated that the units lost 37,780 km2, and the corridors lost 45,979 km2 of forest in 12 years.

Olsoy explains that corridors increase jaguar genetic diversity, reduce inbreeding and help to ensure the long-term survival of the species. Deforestation in these vital areas can isolate populations and lead to the extinction of the local population.

In regard to habitat loss, according to data from SERFOR, in 2016 alone 164,662 hectares of Amazonian forest were lost in Peru. The average loss of Amazonian rainforest in the period 2001-2016 was 123,388 hectares.

Bolivia, according to the Environmental Indicators of the United Nations Statistics Division (UNSD), is seventh among the 10 countries with the highest deforestation worldwide, and its forested area was reduced by 80,310 km2 between 1990 and 2015. Data from the national authorities revealed that in 2016 alone, 325,058 hectares of forest were cleared.

This investigation was published by Internews’ Earth Journalism Network and was funded by a story grant from Arcadia, a charitable fund of Peter Baldwin and Lisbet Rausing. Videos produced by Eduardo Franco Berton for the investigation are on YouTube here, and a photo gallery is here.