29 Jun SA’s wildlife cryptotrade

The South African-based marketplace for online wildlife trade is Africa’s largest. Roxanne Joseph investigates where this cryptotrade is taking place

Here be dragons: We focused on the impact increased access to the Internet has on pangolins, leopards, rhinos and sungazers, a family of lizards endemic to sub-Saharan Africa. Photo: MG Kuijpers/Adobe Stock

A casual search of some of South Africa’s biggest online marketplaces shows just how easily endangered wildlife species are reduced to their parts – and how simple it is to sell them online while retaining anonymity. It will take far more than just a quick search to track down all the cryptotraffickers.

South African wildlife is already facing enormous pressures: habitat destruction, human-wildlife conflict, climate change and global trade. Increased access to the Internet for wildlife trafficking is yet another concern to add to the list.

Over a period of approximately four weeks, from mid-April to mid-May 2018, we conducted a small-scale investigation of three social media networks – Facebook, Instagram and Twitter – and half a dozen online marketplaces – eBay, Gumtree, OLX, Public Ads, Free Classifieds and Bidorbuy.

We focused on the impact that increased access to the Internet has on pangolins, leopards, rhinos and sungazer lizards, a family of lizards endemic to sub-Saharan Africa. Monitoring advertisements using keywords like “scales”, “skin”, “rhino horn” and “dragons”, we found 14 advertisements for animal parts – most for pangolin scales and rhino horns.

Only three of the advertisers responded when asked whether they had the necessary permits, either stopped responding altogether (and subsequently blocked the email address we used), or ignored the question entirely, instead responding with images and questions about where we were located.

It is not possible to be 100% certain if any of the products identified were what they claimed to be, or if they were in breach of the law. Further examination by authorities would be required to assess the legality of the sales, any documentation provided and to obtain information on whether the animal was captive-bred.

This is almost impossible to do if the person assessing the product cannot see it in person, and – as experienced numerous times over this time period – often there is no mention or evidence of the necessary documentation, and the product can easily be disguised as something else to evade detection.

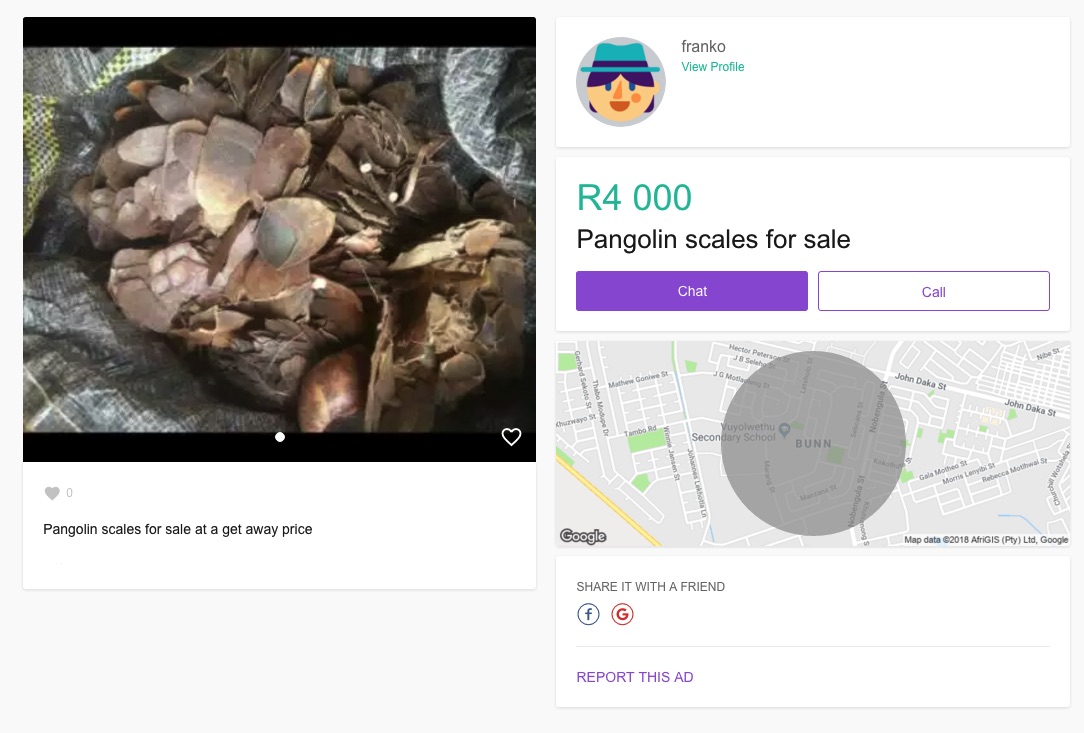

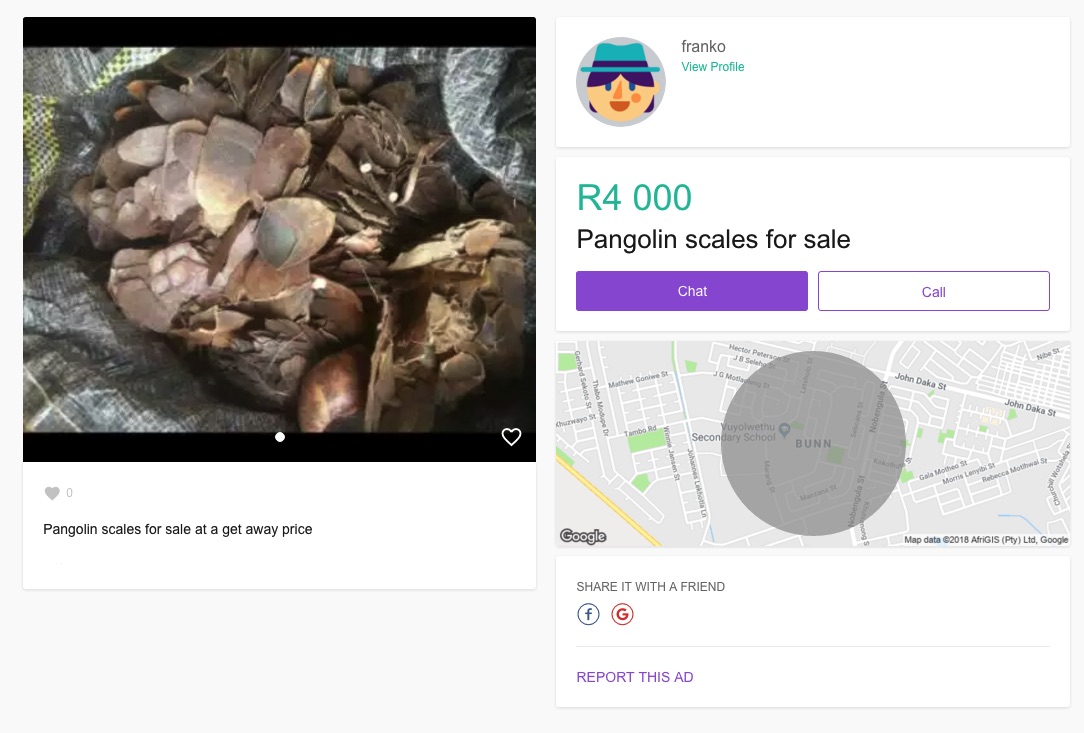

‘Get away price’: An advert for pangolin scales carried by online marketplace OLX

Illegal trade

The International Fund for Animal Welfare (Ifaw) has been researching the threat that global online wildlife trade poses to endangered species since 2004. In its most recent investigation, covering a period of six weeks across seven African countries in 2017, it found 33,006 endangered animals and wildlife products worth approximately $10.7-million (R136-million) being advertised.

The study identified the South African-based marketplace for online wildlife trade as the largest in Africa; Nigeria is not far behind. There are a variety of reasons for this problem in South Africa. These include availability of specimens and lax legislation, and indicate a need for greater enforcement capacity. Internet users must also be better equipped with knowledge and understanding about the problem.

In South Africa, more than 8,000 specimens were found to be for sale. About 400 of these were live animals, and 322 of them are threatened with extinction under CITES Appendix I. The remainder are not immediately threatened with extinction but may become so, under CITES Appendix I or II.

The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna (CITES) governs commercial trade in endangered and threatened wildlife, through the use of permits and certificates for species listed on its appendices. Trade without the proper documentation is illegal.

In the past two decades, it has become more challenging than before to distinguish legal from illegal trade on the Internet. This is one of the reasons why it has quickly become such a popular marketplace: anonymity coupled with simple evasion tactics make tracking the path a specimen takes from start to finish a difficult task.

There appears to have been a shift in recent years from online marketplaces to more private online forums – in spaces like WhatsApp chat threads and closed Facebook groups – and social media platforms.

Although sales don’t always take place online, at least one step in the process usually does. In Wanted – Dead or Alive, Ifaw found that a good proportion of sellers used social media as the main method of contact between sellers and buyers.

No matter how much research has been done, however, it is nearly impossible to measure accurately the scale and nature of trade across online marketplaces and social media platforms. This would require “scraping” – the process of extracting data from a website – the entire Internet, which is not yet possible.

African greys: South Africa is the largest exporter of live birds, plants and mammals. Photo: Diana Neille

Access to data

One of the major issues faced when trying to track the value chain for commodities such as pangolin scales, rhino horns, leopard skins and sungazer lizards is the lack of access to data, which leads to an absence of interpretation and makes it difficult to determine how big the problem is.

Analysis of CITES data on exports of fauna and flora from Africa to Asia between 2006 and 2015 indicates the scale of the legal global trade: 1.4-million live individuals and 51 different commodities were exported. The analysis, conducted by wildlife trade monitoring network TRAFFIC, shows South Africa was the largest exporter of live birds, plants and mammals.

When it comes to legally traded wildlife, legislation allows a certain number of a particular species to leave the country, taking into account factors such as the species’ conservation status, trade and harvest levels. The problem emerges when more than the allowed amount is exported and when trade that could have remained legal instead becomes illegal.

Alongside the stepping up of law enforcement efforts, through knowledge-sharing and training, and the strengthening of national legislation, conservation NGOs are encouraging the online sector to force illegal transactions off their platforms.

In recent months Facebook, Google and Instagram have implemented warnings, stricter seller-buyer policies and links to organisations involved with wildlife conservation.

With the rise in online marketplace and social media platform policies, combined with increased data collection, it will be vital to monitor these implementations continuously and for companies and Internet users alike to report any suspicious activity – no matter how insignificant they may think it seems.

NEXT: Where and how the Internet is being used to advertise specific wildlife commodities

This is the first of a six-part series, in partnership with Oxpeckers, on online illegal wildlife trade within and linked to South Africa. Research was funded by the Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime, and support was provided by the Endangered Wildlife Trust, TRAFFIC and the International Fund for Animal Welfare

This is the first of a six-part series, in partnership with Oxpeckers, on online illegal wildlife trade within and linked to South Africa. Research was funded by the Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime, and support was provided by the Endangered Wildlife Trust, TRAFFIC and the International Fund for Animal Welfare

• Grey area: Oxpeckers investigation into the illicit parrot trade and SA’s captive-breeding industry