21 Feb Christo Wiese’s Namibian rhino deal under scrutiny

How did 13 rhino bulls from the Kruger National Park end up on a hunting farm owned by a reclusive Russian billionaire in Namibia? John Grobler and Khadija Sharife follow the trail

Rashid Sardarov in pith helmet poses with a black rhino he shot at John Hume’s Mauricedale Game Reserve in Mpumalanga, South Africa. Photo: Thormählen & Cochran Safaris

Shortly before South African billionaire Christo Wiese was forced into a fire sale of his Shoprite shares and other assets in the wake of the Steinhoff accounting melt-down in early December 2017, his rhino deals in Namibia came under scrutiny.

Wiese’s game-dealing venture, Kalahari Oryx Game Breeding, is a partnership with Northern Cape game breeder and professional hunter Jacques Hartzenberg. Oxpeckers reported in 2013 that the partnership had contracted to buy white rhinos from the Kruger National Park (Kruger rhinos to Northern Cape).

In November 2017, it emerged that 13 of the Kruger rhino bulls sold to them by South African National Parks (SANParks) had ended up on a private hunting farm in Namibia belonging to reclusive Russian billionaire Rashid Sardarov.

The deal had its origin in 2013 in a controversial decision by the then SANParks head of conservation Hector Magome to sell 500 white rhinos – later reduced to 260 rhinos – to three private game breeders in the Northern Cape, without a formal board mandate and before making any public announcement of the offer, according to SANParks documents.

A review by auditors Sizwe Ntsaluba Gobodo in February 2015 of Magome’s sales agreements indicated they were unprocedural on several grounds. The review, obtained from a private investigator with ties to the rhino industry, indicated Magome had in at least one case started official negotiations two months before any official notice of SANParks’s intention to sell off a large number of rhinos was published in December 2014.

Although ostensibly sold for breeding purposes and to reduce poaching in the “rhino sink” of the southern Kruger park, many of the rhinos ended up on too-small and often insecure farms – or on hunting farms of questionable repute, the review showed.

The review also raised red flags about missing rhino horns taken from animals that died in the translocation process. In terms of the sales agreements between Magome and the buyers, such rhinos would be replaced but the horns had to be returned for safe-keeping by SANParks.

Documents provided by a private investigator with insider knowledge of SANParks show close to 100 rhinos were sold to John Hume, owner of the world’s largest rhino farm and a pro-trade proponent. In 2009 Hume reported “a huge loss” among 60 white rhinos moved from the Kruger to his farm in North West province, due to cold weather, capture stress and lack of adaptation to the local grass.

Hume requested compensation for the loss of the rhinos, and some of the rhinos were replaced. The documents indicate that the horns of the dead rhinos were not recovered by SANParks, as stipulated in the sale agreements.

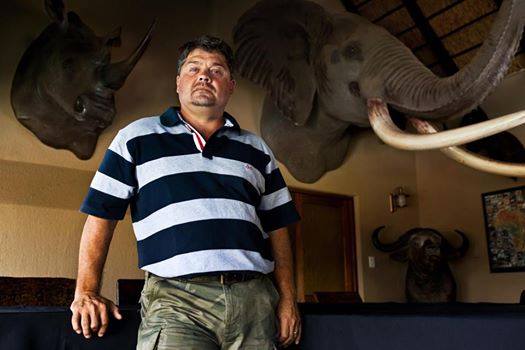

Six of the Kruger rhinos ended up on the farm belonging to Dawie Groenewald, allegedly the mastermind behind South Africa’s largest poaching syndicate. Photo: Fight for Rhinos

Rampant poaching

Six of the rhinos sold to Hume ended up on the farm Prachtig belonging to Dawie Groenewald, allegedly the mastermind behind South Africa’s largest poaching syndicate. Dubbed “the Musina Mafia”, the syndicate faces 1,872 charges of racketeering, illegal possession of and illegal dealing in rhino horn, fraud and defeating the ends of justice.

Groenewald and his brother Janneman are also fighting extradition to the United States, after the US Department of Justice charged in 2014 that the brothers had illegally sold rhino hunts to American clients under the pretence they were problem animals. The brothers face an 18-count indictment for alleged conspiracy, Lacey Act violations, mail fraud and money-laundering charges.

The Department of Environmental Affairs has not responded to a list of detailed questions repeatedly sent to them. Questions sent to Christo Wiese and Kalahari Oryx have also not been answered.

Rampant poaching and the high costs of protecting rhinos against poaching caused prices at a recent SANParks game auction to drop to around R500,000 or R15,000 per 2,5 centimetres of horn for a prime, breeding-age rhino bull, said a Namibian rhino breeder, speaking on condition of anonymity due to security concerns.

Prices for trophy hunting a white rhino have, however, increased as hunting quotas were reduced as result of the increased poaching, he said. Fees range from R825,000 to more than R1-million for a trophy-quality bull, depending on the size of the main horn as measured in length and base circumference.

Excess bulls

Selling excess rhino bulls into the hunting industry is not new in the game breeding industry, the Namibian said. The recovery of the South African white rhino population, once on the brink of extinction, to around 22,000 animals presently was in large part due to SANParks’s policy of selling rhinos to the commercial breeding industry to maintain genetic diversity.

With half of all rhino calves born being male, this has led to an excess of rhino bulls in the market and they are mostly sold off into the hunting industry, said the breeder. “It’s sad, but rhinos are often worth more dead than alive,” he said.

Dr Pierre du Preez, a member of the Namibian Rhino Working Group and deputy director in charge of the Etosha National Park, said: “In short, if there are no financial incentives for the private sector in breeding white rhino, there might be a lot less investment in rhino and more so now with APU [anti-poaching units] costs,” he said.

Pictorial evidence submitted in court shows the fence at Marula to be of extremely poor quality and unlikely to be able to contain impalas, much less a two-and-a-half-ton rhino bull. Photo: John Grobler

The devil in the detail

SANParks’s records showed that in some cases, some of the breeding farms where the rhinos were sent were far too small (only 800ha in one case), lacking in grazing, or even more exposed to poaching than the Kruger, due to their proximity to densely-populated, poor areas.

Marula Game Ranch, which Sardorov invested in through his company Comsar Properties SA, spans 29,500ha near Windhoek’s Hosea Kutako International Airport. Sardorov is the founder of Comsar Energy Group and South-Ural Industrial Company, both large private companies in Russia with a presence in several countries in Eastern Europe, and he was listed in the Panama Papers exposé of international businesspeople with offshore shell companies in tax havens.

Sardarov is a keen hunter and has three rhinos trophies on his wall, including one of a critically endangered black rhino. He had originally in 2013 made a deal to buy 40 or 50 rhinos from Wiese, Marula general manager Johan Kotze said.

In the end, he bought 16 or 17 rhino bulls from Kalahari Oryx, two of which were swopped for cows. “The plan was to have 50 rhinos [on Marula, but Sardarov] refused to buy de-horned rhinos,” said Kotze.

SANParks halted the Kruger rhino sales to the Northern Cape following the Oxpeckers exposé in 2013. Kalahari Oryx signed a new contract with SANParks in March 2015, and 92 rhinos were sold to the outfit in 2015 and 2016 for R18-million.

“Most of our rhino sales are bilateral agreements between countries. When it comes to individual buyers, there is a clause in the contract stipulating that no rhinos must be removed or hunted during a particular period. In the case of Kalahari Oryx, this was a three-year period,” said SANParks spokesperson Janine Raftopoulos.

Only 12 younger and one older bull were eventually delivered to Marula. Kotze said the rhinos were kept in the Northern Cape until Marula could complete upgrading a game-proof fence.

While South African regulations require a dangerous game fence – electrified and reinforced with steel cables – Namibia’s outdated regulations require less secure fencing. A certificate was issued on March 20 2014 verifying that Marula’s fence complied with the standards set by Namibia’s Ministry of Environment and Tourism (MET).

In a High Court appeal against wrongful dismissal filed recently by Willa Liebenberg, a former Marula employee, pictorial evidence was submitted showing the new fence to be of extremely poor quality and unlikely to be able to contain impalas, much less a two-and-a-half-ton rhino bull.

Liebenberg said the fence was inspected by a junior MET employee who previously was employed by Erindi Game Reserve, another private Namibian game reserve that had sold several rhinos to Sardarov. This employee subsequently resigned from MET, and could not be reached for comment.

While South African regulations on trade in endangered species specify that white rhinos may only be exported for breeding purposes, Hartzenberg supplied Marula with 13 rhino bulls. Kotze conceded that importing bulls only could create the impression that they were imported for hunting purposes, but only one rhino had been hunted at Marula – in October last year.

Sardarov’s regular hunting companion, Corné Kruger, said he met the billionaire in 2004 and had done three rhino hunts – including of two critically endangered black rhinos – with Sardarov since then.

Sardarov recently raised eyebrows when he offered to pay N$24-million to the Namibian Land Reform Ministry to approve his buying an additional 10,000ha of farm land around Marula. This was to accommodate 20 elephants he had bought from Erindi but couldn’t move to Marula because he feared the elephants would destroy a precious copse of ancient camel thorn trees, said Kotze.

There were other problems at Marula: nine rhinos had died from either fighting or contracting anthrax within months of their arrival at the ranch. Anthrax is a known problem in Namibia, but can be easily addressed.

Kotze said because the rhinos had been tranquillised for relocation, no inoculations could be administered. But another rhino breeder scoffed at this claim: antibiotics are routinely administered before importing white rhinos, he said, although it is expensive to do because the animals have to be darted, usually from a helicopter.

Asked whether this created the impression that Kalahari Oryx wanted to get rid of their excess rhino bulls at a minimum cost and a handsome profit, Kotze conceded it was fair to say that Hartzenberg and Wiese had taken full advantage of Sardarov’s deep pockets and lack of knowledge.

This investigation is a collaboration between Oxpeckers Investigative Environmental Journalism and the Organised Crime and Corruption Reporting Project