09 Aug State forest capture

Ancient hardwood trees in the Caprivi State Forest are being looted by a Chinese syndicate exploiting legal loopholes and de-bushing tenders for farming. John Grobler investigates

The contract purportedly gave the syndicate the right to cut down any tree thicker than 15cm. At that age, a rosewood is 15 years old, growing 1cm per year in diameter. Some trees here are over 1.5m wide at the base, meaning they are older than 150 years

For about 12 kilometres west from Katima Mulilo, along an old smugglers’ track running along the Zambian border cut-line, hundreds of teak and rosewood trees lie silent, grey and dead, their cut-off trunks oozing red resin, much like the blood of the elephants that once inhabited this stretch of state forest before poaching saw them all disappear.

Like the demand for ivory, the current Chinese craze for redwood furniture as a status symbol has ignited a logging rush on the Guibourtia coleosperma that is devastating sub-Saharan Africa’s ancient hardwood forests to feed Chinese appetites for luxury goods.

But unlike the elephants, these forest giants cannot flee the howling chainsaws coming at them as six two-man teams of loggers employed by a Chinese syndicate headed by businessman Hou Xuecheng approach relentlessly approach from the east.

Bloodwood

A member of Hou’s syndicate, former Otjiwarongo shop-keeper Wang Hui, is currently serving a 14-year jail sentence in the Windhoek central prison with three other Chinese nationals for rhino horn smuggling in 2014.

What they were doing here was also criminal: their contract purportedly gave them the right to cut down any tree thicker than 15cm. At that age, a rosewood is 15 years old, growing 1cm per year in diameter. Some trees here are over 1.5m wide at the base, meaning they are older than 150 years.

A loud crack that sent a shudder through the Caprivi State Forest heralded the fall of another one.

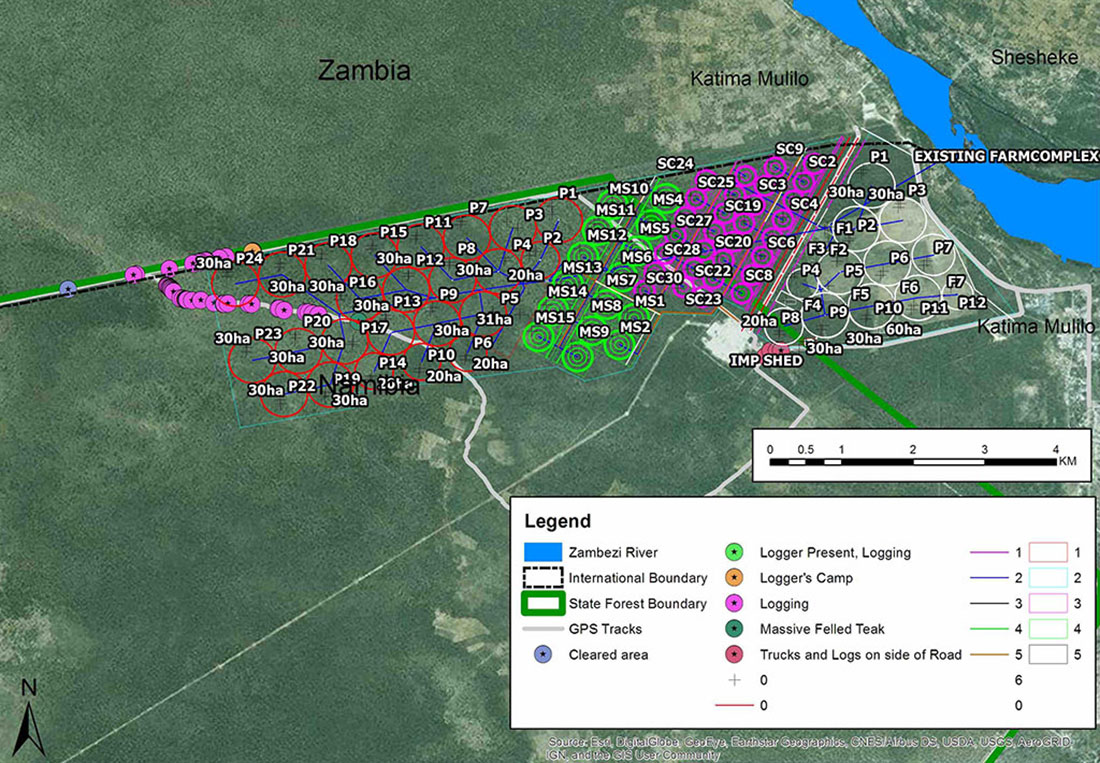

Covert surveillance established the pattern: every morning for three days, the Chinese foreman would drop the teams off deep in the state forest, several kilometres away from where they were supposedly cutting trees in an area being de-bushed for a tobacco-growing scheme at Katima Farm.

Carrying water and fuel, they then fanned out, looking for the densest copses of rosewood and teak, where they cut down the oldest trees before dismembering them in order to dry the wood quicker. The oldest ones oozed the deepest red resin.

Later, a heavy front-end loader would be brought in to to rip open a path for the machine that lifted the logs onto a rickety trailer and moved them to an area where several hundred trees already had been piled at a camp next to the Nampower sub-station.

The Chinese foreman, Li Weichao, approached a few days later at a service station and informed they were harvesting illegally, became threatening and refused to discuss their activities. “I no talk to you. I only talk to government.”

“You no come here again, you see what happens,” he snarled.

It’s back-breaking work, six days a week for payment of N$100 a tree, said one of the logging teams’ saw-men. “My best total for one day of cutting was 60 trees,” he said.

With six two-man teams cutting every day, that quickly adds up to serious deforestation. Already, an area of more than 8,000ha has been felled of what had been untouched forest since at least 1968.

That year, the apartheid-era officials ordered all the local people out of the area and resettled them further away from the border for security reasons, building a huge military airport (“Mpacha”) and base on the southern edge of the 400 square kilometres Caprivi State Forest.

With six two-man teams cutting every day, that quickly adds up to serious deforestation of what had been untouched forest since at least 1968

No state forest declared – ever – in 15 years

No explicit proclamation of the Caprivi State Forest has ever been issued, by either the colonial authorities (1914-1989) or the SWAPO government since then, in spite of the promulgation of the Forest Act (Act 12 of 2001) that was intended to address this legal shortcoming.

Article 13 of the State Forest Act prescribes the manner in which state forests are to be declared, in conjunction with the Ministry of Land Reform and the regional land councils, to protect forests of national importance for their biodiversity by way of issuing a Government Gazette or Ministerial Notice.

But in two extensive interviews a week apart, Director of Forestry Joseph Hailwa could not produce proof of any Gazette or Ministerial Notice that legitimised the Caprivi State Forest – or any of the other five state forests – under the Act his office was responsible for putting into effect.

As director of Forestry and secretary to the statutory Forestry Council set up to administer the Act, the buck stops with Hailwa’s office: this was his responsibility, by law.

Pressed hard to prove it, he angrily blurted out eventually that “Caprivi State Forest was declared by the Pretoria government!”, admitting in effect to his failure to fix this problem during his 15 years in office. Hailwa could not give any reason for failing to do so.

The buck stops here: Director of Forestry Joseph Hailwa

He also admitted he had ordered the return of Chinese chainsaws, seized on February 2 from forestry wardens in Katima Mulilo for cutting in the Caprivi State Forest, west of the Liselo farm boundary.

“I told my staff members to make sure that they cut outside the area” of the Katima and Liselo Farms, he said. But the evidence on the ground contradicted this: those same staff members were encountered deep inside the state forest, in the Chinese foreman’s vehicle, taking stock of the harvest.

Since at least the beginning of May, forestry staff have been keeping book of all logging in the state forest because, Hailwa said, “those trees are not just for mahala”. He then somewhat shamefacedly admitted the Chinese were paying only N$200 per mature tree of 10 cubic metres that, converted to timber, sold for at least N$25,000 in China.

The harvesting permit was a tender issued to de-bush two irrigation fields, he initially insisted – but later admitted to only one such permit issued for Katima Farm, which had largely already been de-bushed in an earlier, failed attempt to grow jathropa.

“The tender is the harvesting permit,” he insisted.

As for the accusation that he had knowingly enabled the Chinese syndicate’s illegal logging in the adjoining state forest by ordering their chainsaws returned, he said he had ordered his staff members to investigate as soon as he was informed by this reporter of the fact.

This happened last week “… Wednesday or Thursday”. He had now ordered an investigation into the operation, he said.

The earlier confiscation was based on a misunderstanding, he said: his officials had been unaware that they were entitled to harvest trees under the de-bushing tender, issued under the Ministry of Agriculture, Water and Forestry’s Green Scheme project to increase food production.

“If I have proof that they are cutting outside the area [they’re supposed to stick to], then I will order that wood confiscated,” Hailwa said during the first interview.

“My staff said they were within the legal area,” he later said. But the staff members were prohibited from speaking to the press by Hailwa: any queries could only be answered by the Department of Forestry, they said in Katima.

The blurring of legal boundaries and official lines of responsibility has facilitated a ‘contract creep’ from 2,000ha to over 8,000ha of de-bushing – and likely much more

Blurring boundaries, responsibilities

The land in question resorted under the Ministry of Land Reform, the Regional Land Board and the local Mafwe traditional authority, Hailwa said. The harvesting agreement between the Mafwe and the Chinese syndicate was within the framework of the Forest Act, he insisted.

Pressed to produce a map to show the boundaries of the area to be de-bushed, he could not do so or point to anyone in his department who had that information. This was the responsibility of the Directorate of Agricultural Extension and Engineering Services, he said.

The blurring of both the legal boundaries and official lines of responsibility between ministries has facilitated a “contract creep” from 2,000 hectares to more than 8,000 hectares – and possibly more.

Sources in the Forestry directorate said there were plans to dish out various tracts of land amounting to 25,000ha to various private and public entities, all within the Caprivi State Forest.

Hailwa acknowledged these projects, but also could not provide any gazetted notice of revocation, as required by Article 17 of the Forest Act.

The main political driver behind the entire scheme is a promised Chinese investment of N$14-billion in a 10,000ha tobacco farm on Katima Mulilo’s western outskirts, punted by key politicians like Lands Reform Minister Uutoni Nujoma and SWAPO organiser Armas Amakwiyu over objections from everyone except the local Mafwe traditional authority.

Illegal tender procedure

To understand how the lines of responsibility were deliberately blurred to allow this plunder, one has to go back to July 2016, when two tenders – one for de-bushing irrigation fields, the other to fence in the area – were issued by the Ministry of Agriculture, Water and Forestry.

Forty-seven bids, ranging from N$4.8-million to an astronomical N$441.7-million, were received for the de-bushing contract, and 46 offers ranging from N$6-million to N$43.6-million for the fencing job.

Both tenders were specifically written for black economic empowerment (BEE) tenderpreneurs: 51% of the company had be Namibian-owned, of which 30% had to be from previously disadvantaged groups, according to the Tender Bulletin, which monitors all public tenders.

Although the de-bushing tender was awarded to a certain “MK Capital JV Okatomba Investments” by the Tender Board (and confirmed by the Ministry of Agriculture, Water and Forestry), the job was sub-contracted to Uundenge Investments CC, owned by Laban Kandumo and Ikwambi Amadhila.

Uundenge did not enter a bid for either contract, but then was also appointed as the fencing contractor – in spite of having been deregistered some time ago for failing to submit annual returns.

By late November 2016, Kandume had started asking around in Katima Mulilo for heavy equipment, said Bertus Coetzee, a veteran of Caprivi’s wood wars and owner of a local lodge. “This guy didn’t have a clue about wood or de-bushing, or where he was supposed to work,” said Coetzee.

No clarification could be obtained from the Tender Board about who originally had been awarded the fencing contract: all copies of the original tender documents had disappeared.

Substituting contractors in this manner was a clear violation of Tender Board regulations which require that the original bidder stipulate in writing that he or she intends sub-contracting the job out, said lawyer Eben de Klerk, a financial fraud expert.

“What this likely amounts to is misrepresentation, or even fraud, and [the tender] should have been cancelled and re-issued,” he said of the deal.

Hailwa, however, did not have either the map or coordinates used by the Chinese loggers now, and therefore could not tell whether they were working within the designated area. “Bring me the hard evidence, and I will take the wood from the trees cut outside [the construction area],” he said.

A Google Earth map, marked up with GPS data showing how far the Chinese loggers were working outside of the designated area, was sent to Hailwa’s office after the first interview last week Tuesday.

The Chinese logging operations were suspended last week – but Hou’s trucks were still allowed to load out the timber they have harvested so far.

Trucks loaded with hardwood timber from the DRC parked at Katima Mulilo. The current Chinese craze for redwood furniture as a status symbol has ignited a logging rush that is devastating sub-Saharan Africa’s ancient hardwood forests

‘Farm trees sales agreement’

Hailwa’s claim that no harvesting permits were required was further undermined by the agreement between the Chinese syndicate and Uundenge.

In early January, Uundenge CC signed a contract with Hou Xuecheng’s company, New Force Logistics. Titled “Farm Trees Sale Agreement” and signed and date-stamped January 5 2017, it stated (verbatim):

“Main Contractor Uundenge Investments cc possessed Katima/Liselo development bush clearing & ripping projects from Ministry of Agriculture, Water & Forestry, Namibia. The description for the project is the DEBUSHING AND RIPPING OF IRRIGATION FIELDS AT KATIMA FARM LISELO IN THE ZEMBEZI REGION – MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE, WATER & FORESTRY.

On this premise, after the main contractor and subcontractor got fully discussion and communication,both Parties reached the agreement on Katima and Liselo area trees cut, fell, transport, transaction.

The contract is as follows:

“1. Sub-contractor can fell, transport, sell any diameter beyond 0.15m trees in the appointed construction area […] and the trees variety is unlimited.

2. Main contractor assist sub-contractor to apply for those permits and documents about requiring for felling, transporting, selling these trees, and the cost undertake by the main contractor.” (sic)

It then went on to stipulate dates of commence (completion set for June 1), and then agreed:

“4. Sub-contractor agreed to pay main contractor, the the total amount is N$3,000,000 (three Million Namibia dollars for all the trees which they are going get […]” (sic), with payment to be made in tranches of N$1-million payable on the first days of March, May and June.

On the face of it, both the contractor and buyer were aware of the legal requirement to obtain harvesting and transport permits, with Uundenge’s Kandume responsible for paying for procuring those permits.

No application of any kind had been filed by Uundenge, Hailwa said.

Official policy ignored, circumvented

Both the Department of Forestry and the Ministry of Land Reform were also acting in contradiction to the Integrated Land Use Plan for Zambezi (IRLUP-Z), approved in July (just as the de-bushing tender was issued) by Cabinet as official reference policy for Caprivi (referred to as Zambezi by the state).

Cabinet decision No. 11th/05/07/19/011 noted the IRLUP and stated: “[…] Cabinet approve the Zambezi Regional Land Use Plan to serve as a reference for all further development in the Respective (sic) region.”

“[…] Cabinet directs Zambezi Regional Council to implement and regularly monitor the [IRLUP-Z] in their region.”

The Caprivi State Forest was off-limits for what the Department of Forestry and the Ministry of Land Reform were planning, according the IRLUP-Z policy document. “No irrigation, crop farming, large scale clearing of land or mining should be allowed in this area,” it stated.

Hard copies of the IRLUP-Z, however, have not been handed over to the Zambezi Regional Council, more than a year after its approval, it was established. It is also not legally binding, a fact that was clearly being exploited by Hailwa and others.

Hailwa was also ignoring the Forestry Regulations he had helped draft, it emerged.

Gazetted as Government Notice 170 of 2015, as issued under Section 48 (1) and (2) of the Forest Act 12 of 2001, the Forest Regulations state among others:

12. (1) A person is not authorized to harvest transport, sell, market, transit, export or import forest produce without a valid license for harvesting or permit for transport, marketing, transit, export or import […]

(3) A person may not export any unprocessed forest produce, including semi-processed planks unless authorized by the Director for special purposes such as research, education, cultural and disease identification for which relevant documents are to be provided as a prerequisite;

(4) A true copy of a license issued under this regulation must accompany the forest produce in respect of which it is issued until the forest produce is processed or exported and must be produced on request to any authorized officer.

None of Hou’s timber exports would therefore be legal – unless he was submitting forgeries to Customs, a Walvis Bay shipping agent explained. Hailwa, however, said no applications were filed by either Uundenge or New Force as this was not necessary: the tender was the permit, he insisted.

Under these regulations, not even commercial farmers are allowed to harvest firewood without a permit on their own land, the Namibia Agriculture Union confirmed.

But in admitting that he had issued a harvesting permit to the Chinese for Katima Farm, Hailwa’s defence fell apart.

The tribal fig leaf

Back-breaking work: the saw-men work six days a week for a pittance of N$100 a tree

Hailwa claimed not to remember any specific details of the de-bushing tender his office issued last year in July. Tender Bulletin records show the Department of Forestry only issued five public tenders last year, two of which were related to this project.

Asked for the map or GPS coordinates for the area to be de-bushed, he said he did not have those details. Two maps had been issued, but he could not say which of his officials had that information. “I have many people working under me, I do not know what they all are doing all the time,” he protested.

But as far as he knew, the area to be de-bushed amounted to 4,000ha. In the second interview, he however vehemently denied saying this: he only said 2,000ha, he claimed.

Senior Mafwe advisor Elias Mueze in an interview with The Namibian on July 10, disclosed that the traditional authority had signed an agreement for 1,600ha for the Green Scheme project.

Mueze lashed out at critics of the deal, especially white people who thought the traditional authority was being taken advantage of by the Chinese loggers and their local partners. The Mafwe traditional authority was receiving some income from the logging, which was being used to upgrade their offices, Mueze said.

“Therefore, the government has all the right to cut down all those trees or to allow any company that has won the tender to cut down those trees from that area,” he was quoted as saying.

Hailwa’s admission that the Caprivi State Forest’s sole legal provenance was the original 1968 decision by apartheid-era Pretoria made nonsense of Mueze’s statements.

In hindsight, it is clear what happened: the Chinese syndicate, realizing that Katima and Liselo Farms contained no commercial wood species, used Hailwa’s failure to declare the Caprivi State Forest to jump the fence and loot the state forest.

This was achieved by using the Mafwe traditional authority’s claim to the 400 kilometres as cover: records showed that objections against the tobacco farm, from the local Land Board to residents, church organisations and NGOs were ignored, contrary to every legal criterion of the Forest Act.

The only question is why Hailwa was allowed to get away with this for 15 years – and on that, he remained silent.

Hou Xuecheng, could not be reached for comment, but in a previous interview, he denied that he was involved in hardwood harvesting and said he only did the transport (with New Force Logistics).

However, another associate, Bin Binbao, previously told Oxpeckers that Hou and convicted rhino-horn trafficker Wang Hui “… were big in the rosewood business.” – oxpeckers.org

Find source documents here

Related investigations:

• Chinese ‘Mafia boss’ turns to timber

• A mysterious dead hand driving Namibia’s poaching

This investigation was supported by The Organised Crime and Corruption Reporting Project