03 Jun The great Karoo stand-off

Mark Olalde revisits the fracking debate, and finds both sides digging in for a protracted fight as legislation and the benefits of shale gas mining become murkier

An ostrich walks through the Karoo National Park near Beaufort West. Environmental activists and Karoo residents fear fracking will bring problems of air and water pollution, as it has elsewhere around the world. Photos by Mark Olalde

Jonathan Deal tries to recall the countless interviews he has given, statements made and meetings attended since he waded into the battle over hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking”, five years ago.

He stumbled into the fight after calling in to a radio talk show to discuss why he felt fracking was a bad idea. That same week, in early 2011, he created an anti-fracking Facebook page that now has close to 13,000 members.

Deal quickly became the face of the anti-fracking movement in South Africa after he started the Treasure Karoo Action Group, and in 2013 he was awarded the prestigious Goldman Environmental Prize for his work.

“In a short space of time, I found myself at the thin end of the wedge,” he says.

The wedge is fighting to keep fracking out of the Karoo, the semi-arid region spanning 380,000 square kilometres where Royal Dutch Shell, Falcon Oil and Gas in partnership with Chevron and Bundu Gas and Oil Exploration, owned by Challenger Energy, applied for permits in 2010.

Initially hailed as a potential saviour to South Africa’s economic and energy woes, fracking instead stalled as it met opposition from environmentalists and communities across the Karoo.

Confidence in fracking’s feasability in the Karoo has since declined. On May 11 2016, at a conference on unconventional gas, the Council for Geoscience cited new evidence from two boreholes showing the presence of economically recoverable shale gas was questionable. (See “Early drill results make presence of Karoo gas questionable“.)

In mid-May 2016, the Treasure Karoo Action Group was joined by other civil rights organisations in submitting a petition to Parliament calling for stringent regulations governing fracking.

Both sides of the debate have now dug in for an extended fight. Falling commodity prices, the lack of exploratory permits and ongoing environmental research throw the future of fracking in the Karoo into question.

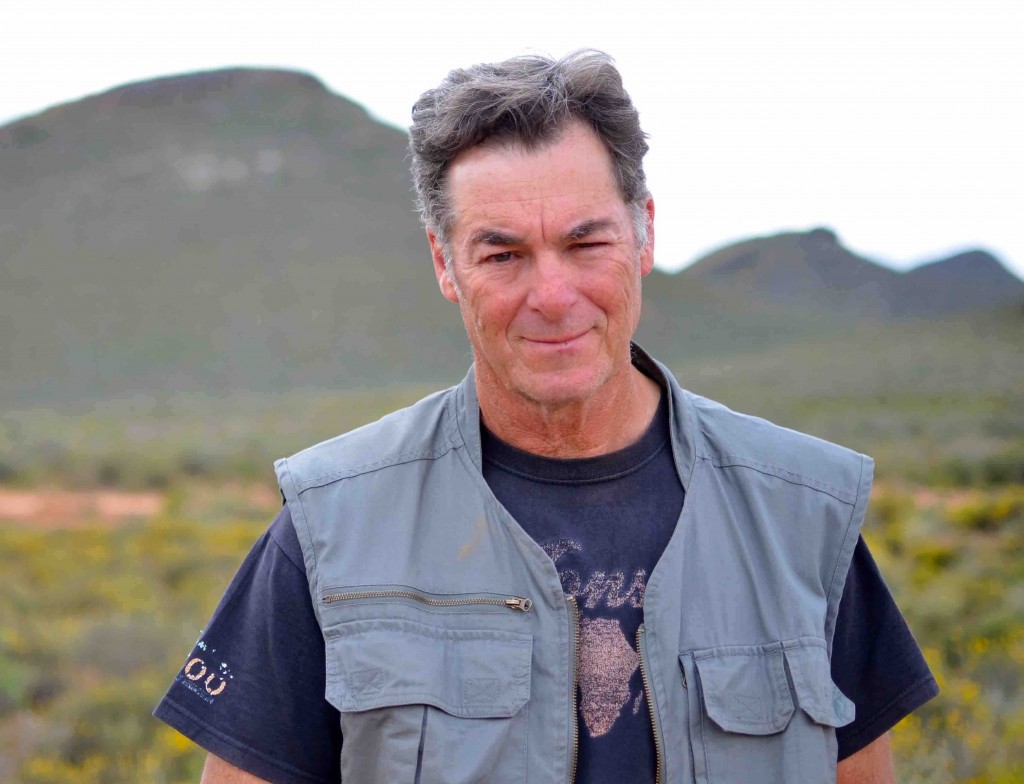

Anti-fracking activist Jonathan Deal at his property in the Karoo. He won the 2013 Goldman Environmental Prize for his fight to preserve the semi-arid region

Dickie Ogilvie, a sheep farmer and head of the Aberdeen Farmers Association, is one of the Karoo residents feeling threatened by the spectre of fracking. He fears for his livelihood in the case of chemicals or gas contaminating the aquifers sustaining his town and livestock.

“Our huge concern regarding fracking is the possible problems associated with our underground waters,” Ogilvie said. “All the drinking water, whether it’s for domestic use or stock use, is underground water.”

David Fig researches fracking from his various positions at the Transnational Institute in Amsterdam, the University of Cape Town and the University of the Witwatersrand. According to his work, fracking a single well would consume at least 20 million litres of water, the equivalent of eight Olympic-size swimming pools. If fracking proceeds in South Africa, hundreds if not thousands of wells could be used.

“[The Karoo] is a thirsty area, semi-arid and very much reliant on its aquifers for all economic activity,” Fig said. About 93% of the Karoo’s municipalities rely on aquifers for water.

In dry years Beaufort West and other towns in the Karoo have resorted to appealing to travellers for donations of bottled water. According to Fig, 30% of the water used in fracking will remain underground, and there have been cases of fracking contaminating underground water sources in other countries.

Fracking also threatens habitat destruction. Although dry, the Karoo is extraordinarily biodiverse and is home to more than 6,000 plant species, at least 40% of which are endemic. The area on which Shell, Falcon and Challenger applied to frack covers roughly 123,500 square kilometres of Karoo habitat.

Fracking has also been linked to induced seismic activity. According to the US Geological Survey, earthquakes of magnitude three or higher occur at least five times as often in parts of the US as they did prior to 2008. Research linked much of this activity to injecting fluid deep underground, a disposal method often used in fracking.

The results of a two-year strategic environmental assessment to determine the full extent of fracking’s potential environmental impacts are expected to be published by the Department of Environmental Affairs in 2017.

“We are supportive of a proper regulatory regime to govern the industry and believe that this is in all parties’ best interests,” Challenger’s managing director, Robert Willes, said in a statement responding to questions from Oxpeckers.

Willes said all environmental impacts would be manageable if Challenger were to begin fracking in the Karoo.

A Royal Dutch Shell petrol station in Touws River. In December 2010 the international oil and gas company applied for licences to explore for shale gas in the Karoo

Energy security

Energy companies and the Department of Mineral Resources argue that gas production could provide South Africa with much-needed energy security and help the country shift from its near-total reliance on coal.

“Shale gas has the potential to become an alternative energy source and thus contribute towards ensuring security of energy supply,” the department’s spokesperson, Ayanda Shezi, said in a statement to Oxpeckers.

However, the infrastructure necessary to bring shale gas into South Africa’s energy portfolio is non-existent, and fluctuating prices suggest the resource would actually be exported.

Studies published in recent years by organisations including the United States Environmental Protection Agency debunk the idea that gas is significantly more environmentally friendly than coal, and show that methane has more than 25 times the long-term impacts on climate change than carbon dioxide.

“At the end of the day, it’s zero fracking,” Ogilvie said. “Find alternatives for this type of energy.”

Evolving regulations and markets are adding little clarity to questions of how fracking might commence.

World Wildlife Fund-South Africa’s Saliem Fakir wants to know who would pay for the environmental clean-up when wells inevitably run dry. “[Fracking is] like mining. If you don’t have funds to go and rehabilitate deteriorating wells, somebody else is going to pay for that,” Fakir said.

A klipspringer in the Karoo National Park in Beaufort West, where water scarcity results in rationing by the local municipality and complete reliance on borehole water at times

The US Energy Information Administration helped set off the fracking craze in South Africa by estimating the recoverable resource at 485 trillion cubic feet (tcf) of gas. Since its initial estimate, the administration reassessed the reserve to 389.7 tcf to account for protected areas that would not be fracked.

If the most recent estimates are correct, South Africa still has the eighth most unproven shale gas reserve of any country in the world. However, according to the Department of Mineral Resources, the administration’s estimate is the high end of the spectrum, with other sources placing the reserve as low as 36 tcf, dropping South Africa’s shale gas reserve to 27th in the world.

Without further exploration, it is impossible to know exactly how much gas is recoverable from the Karoo’s unique geology. Much of the region sits on dolerite – a volcanic rock – and there is speculation that underground dykes released large amounts of the Karoo’s gas into the atmosphere over time.

According to Shell, a fracking boom could employ as many as 700,000 people, but opponents argue that pre-existing industries would suffer and that Shell’s number is vastly overblown, as it is based on estimates of high reserves.

Research from the University of the Free State found that as many as 1.1-million people financially benefit from tourism in the Karoo, and tens of thousands of people work on the region’s farms.

Residents such as Ogilvie argue that water pollution could kill their livestock business and any environmental degradation would decrease the number of tourists travelling to the Karoo. There is also fear that fracking would disrupt research at the state-of-the-art Square Kilometre Array telescope under construction in the Northern Cape.

“We see no reason – provided there is proper engagement to develop and implement appropriate regulation – why these sectors cannot co-exist harmoniously for the benefit of the Karoo communities as a whole,” Challenger’s Willes said.

Research from the University of the Free State found that up to 1.1-million people financially benefit from tourism in the Karoo, and tens of thousands of people work on the region’s farms

Unanswered questions

With so much uncertainty, and with oil and gas commodity prices plummeting since 2014, energy companies have slowed their operations. Shell pulled its shale team out of South Africa in March 2015, and Willes said Challenger has kept only a small staff in the country for the past year.

Fig said companies are hesitating in response to the government’s increased stake in potential revenue. The state can take a 20% free carried interest share, with the potential for acquiring a higher percentage.

Confusion around the law serves to further slow fracking’s progress, as there is no single piece of legislation solely governing fracking.

According to Fig, there is “a lack of clarity around the law. [Fracking is] still in the realm of speculation, but it’s informed by experiences in other parts of the world,” he said.

Draft legislation was recently proposed to deal specifically with fracking, but it simply referred back to recommendations written by the American Petroleum Institute, a major lobbying group for the US oil and gas industry.

“Any documented issue that manifests itself in the US would be magnified many times here because of the geology, because of the differences in water here, because of the inability of our government to monitor, enforce and prosecute,” Deal said.

As the fight rages back and forth between energy companies and anti-fracking activists, the same question persists: when will exploration begin?

In President Jacob Zuma’s 2015 State of the Nation Address, he stressed the importance of gas to the future of the country’s energy portfolio, said Eskom would be directed to switch its diesel generators to gas, and mentioned the potential reserves in the Karoo.

Then during a speech last August, Zuma was widely quoted saying South Africa would be moving forward with exploration of shale reserves. The Karoo dropped from the 2016 State of the Nation, with nuclear potential taking centre state.

Fracking’s opponents gained a temporary victory in 2011 when the government imposed a moratorium in order to further study potential impacts, but that was lifted the following year.

The Treasure Karoo Action Group and its allies also have pending legal action against the government, which they submitted to the North Gauteng High Court in November 2015 in hopes of stalling any permits from being issued until after the department of environmental affairs’s strategic environmental assessment is completed.

Even if laws are passed and exploration begins, shale gas production will face a lack of infrastructure such as pipelines and roads needed to service the industry.

“A shift from exploration to production is probably 10, 12 years away, even longer possibly,” Fakir said. “Shale gas is not an immediate possibility.”

Back on his property, comfortably off the map in the Western Cape, Deal recalls bursting into tears while describing his love for the Karoo at one of Shell’s public meetings a few years ago. Now dry-eyed, he says he is resigned to continue fighting Shell.

“My core motivation is that I like a good fight,” Deal says. “I thought to myself, ‘Stuff you. Nobody has asked South Africans how we feel about [fracking], and just because you’ve done it somewhere else in the world doesn’t mean you’re going to do it here.’” – oxpeckers.org

Find the draft technical regulations for fracking in South Africa here.

#MineAlert: Find out about the Karoo exploration applications and other mining projects across South Africa here